By Rose Sneyd, PhD Candidate, Dalhousie University, Canada

While the Armstrong Browning Library’s (ABL’s) trove of EBB- and RB-related resources is a magnet for scholars of both poets, I was drawn to Waco, TX, by the library’s distinct collection on Matthew Arnold. As a doctoral candidate writing my dissertation on the connections between the great Victorian poet-critic and the Romantic poet Giacomo Leopardi, I was very fortunate to receive a two-week fellowship to explore the ABL’s intriguing holdings on Arnold last winter.

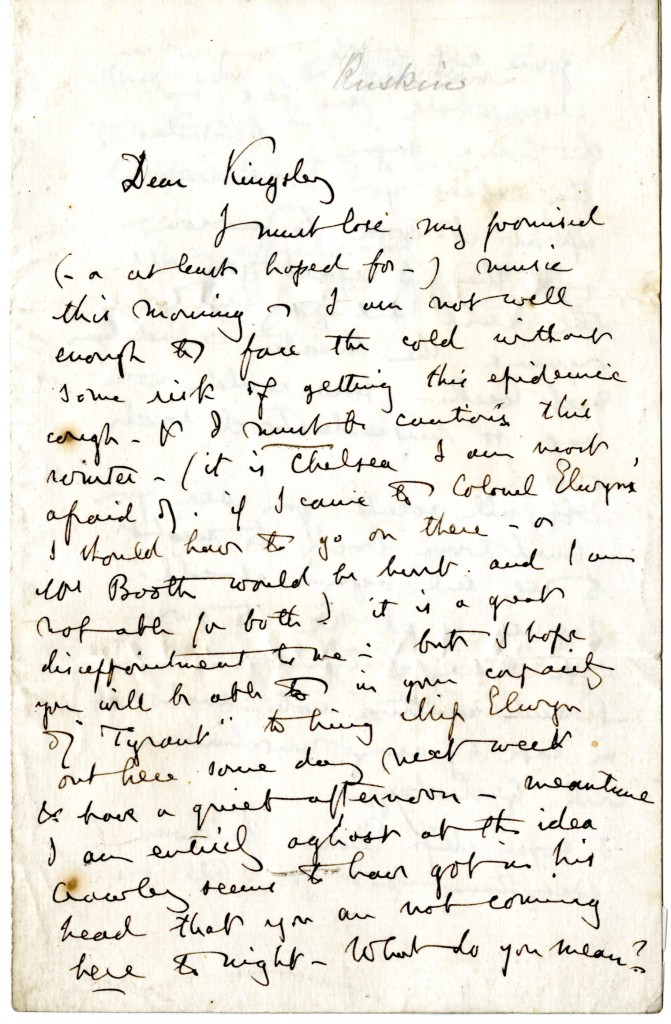

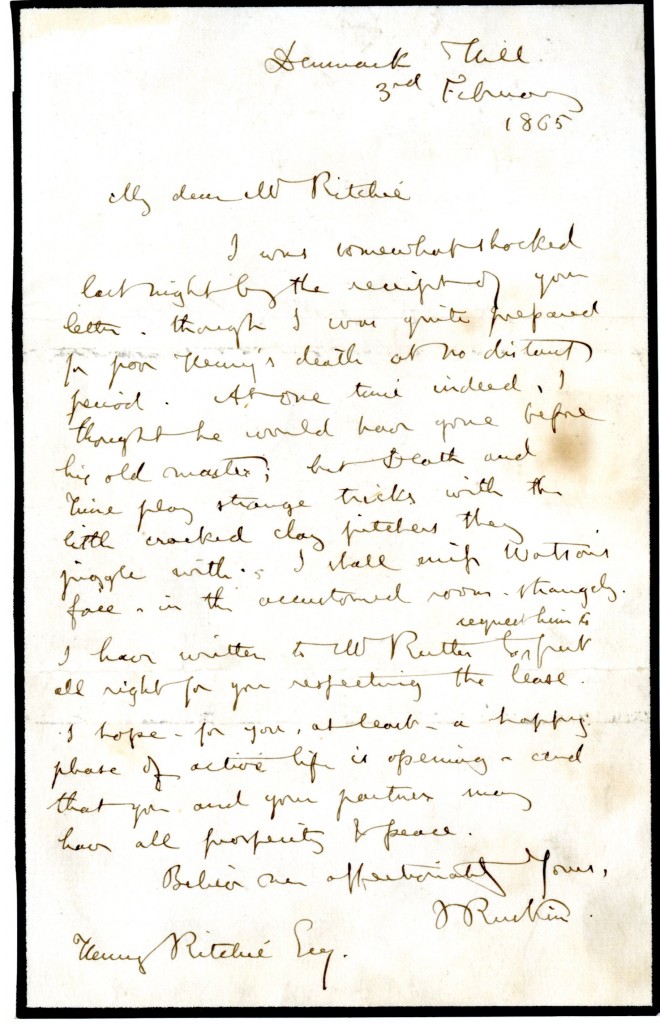

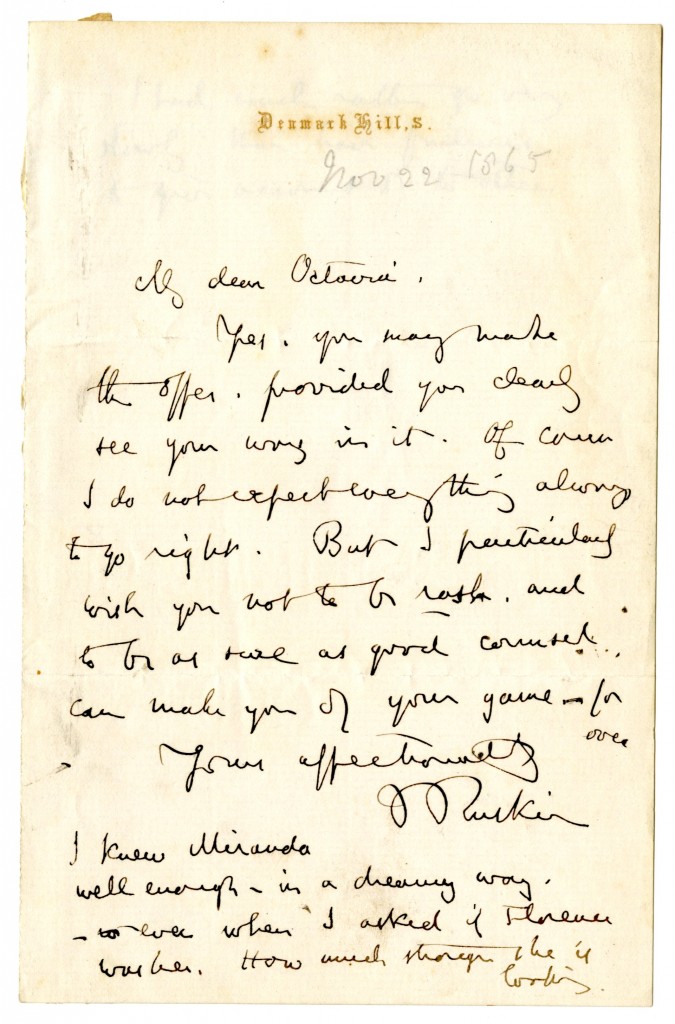

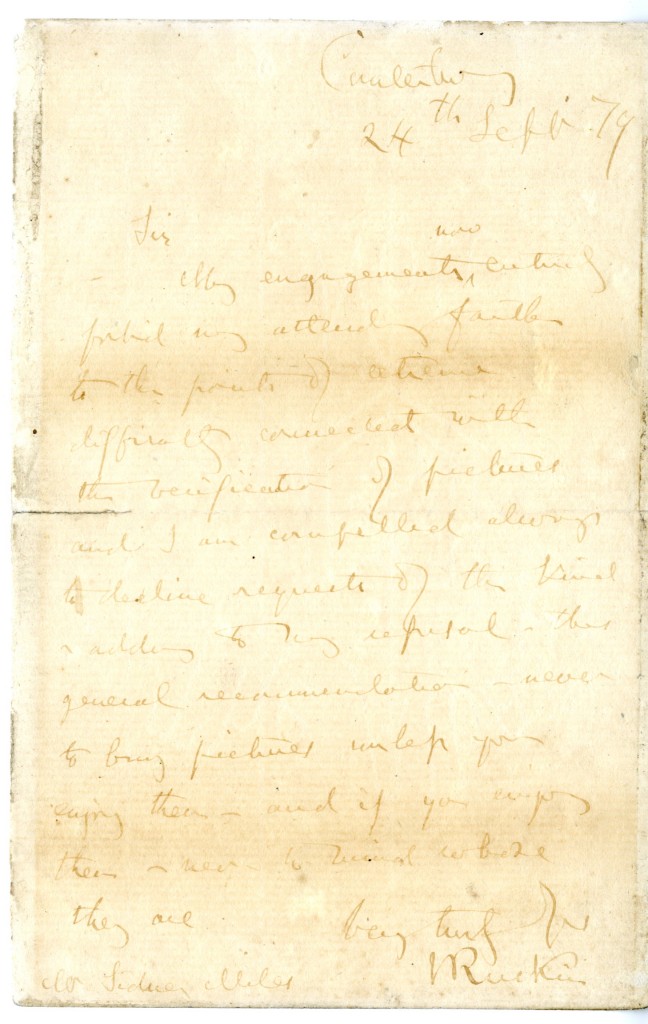

One of several highlights of this collection is those unpublished letters of Arnold that are held by the ABL. These include, among others, an 1865 letter to Sir Theodore Martin – one of the earliest translators of Leopardi’s poetry – who sent his translation of Goethe’s Faust to Arnold, who seems to have approved of it; letters (1866, 1873) to an American journalist and acquaintance of Emerson, Charles F. Wingate, to whom Arnold makes fascinating comments about English reviewers and their tendency to “lose[… themselves] in a number of personal and secondary questions”; and a refusal to produce an entry on Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Chambers Encyclopaedia (1888-92) sent to David Patrick in 1887. Such letters provide vital nuggets of information on Arnold’s network of friends and acquaintances on both sides of the Atlantic.

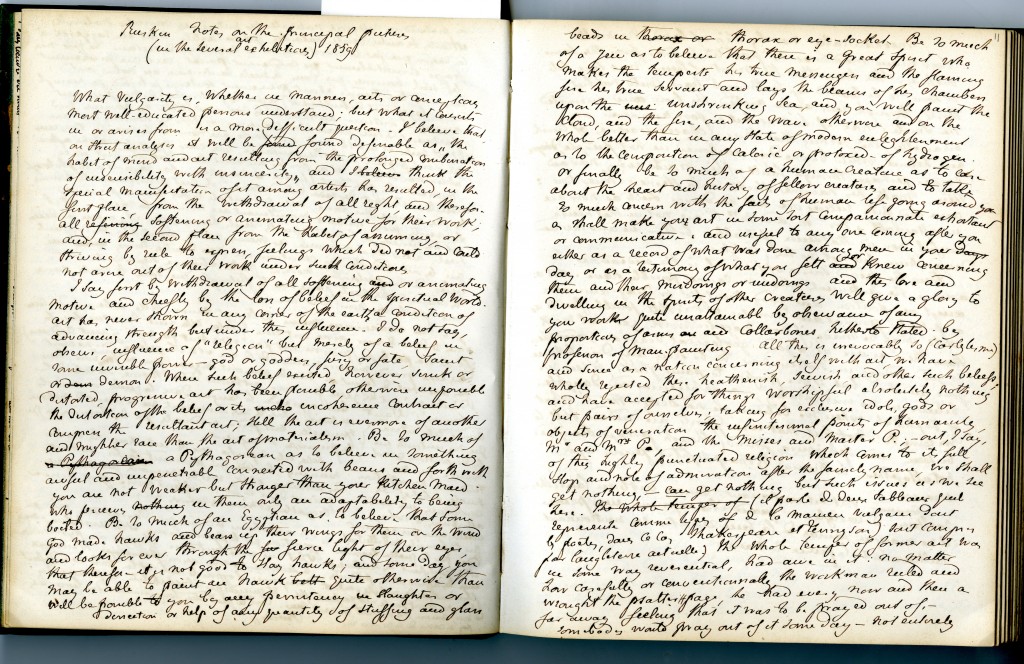

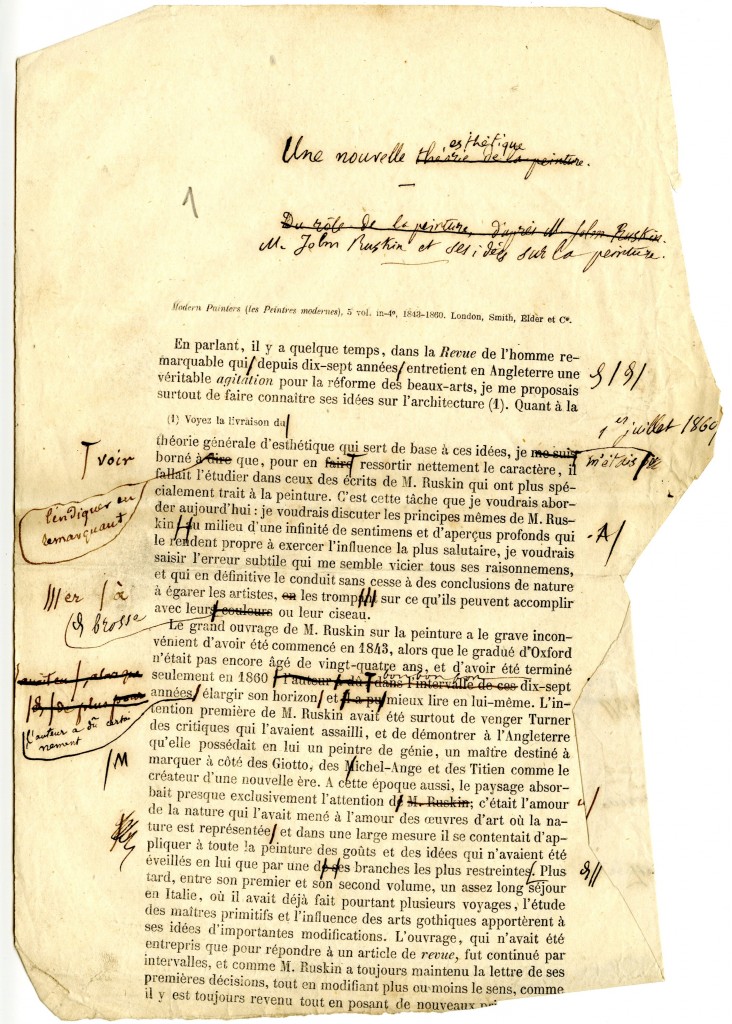

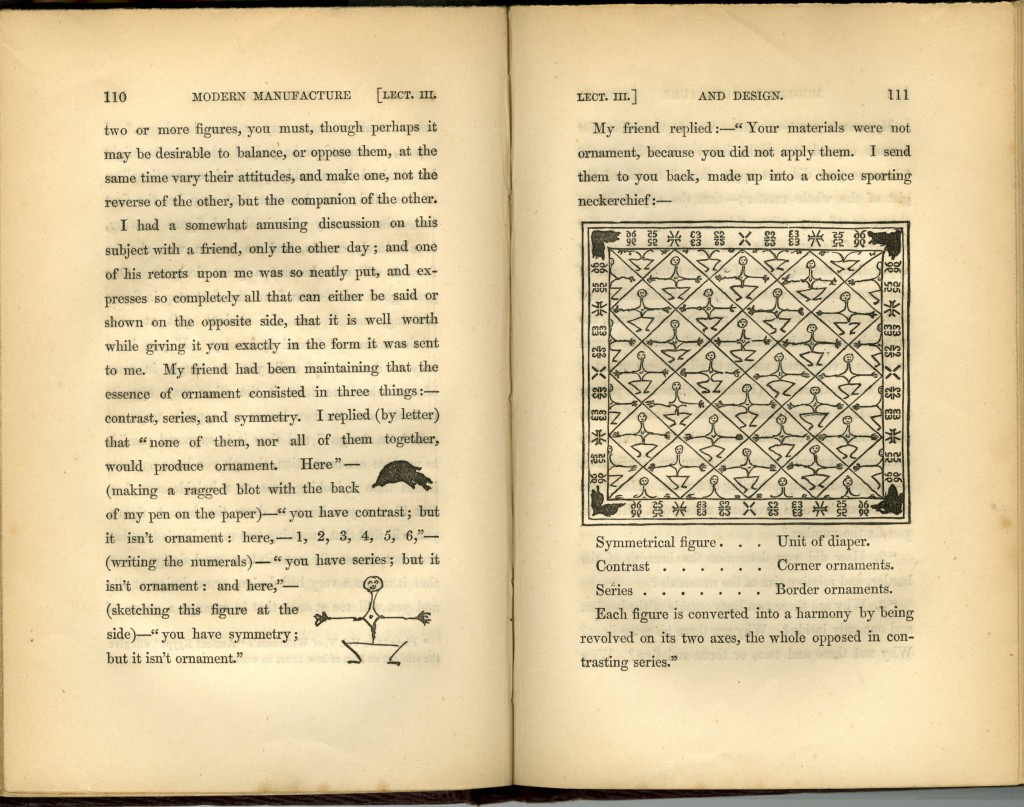

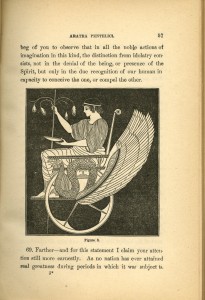

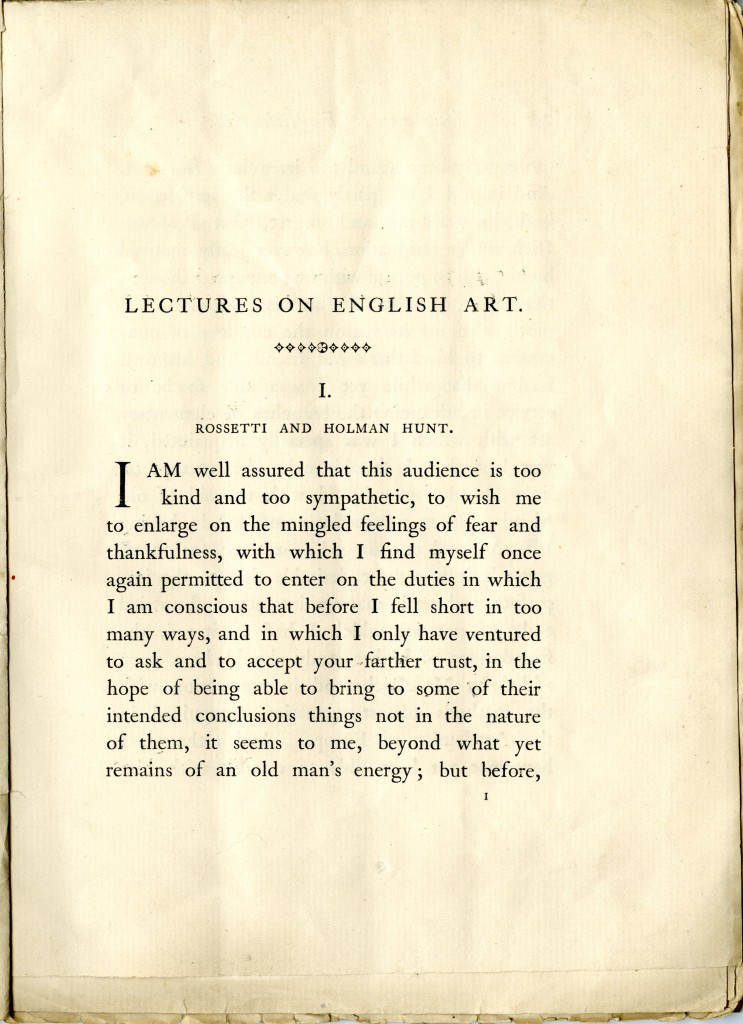

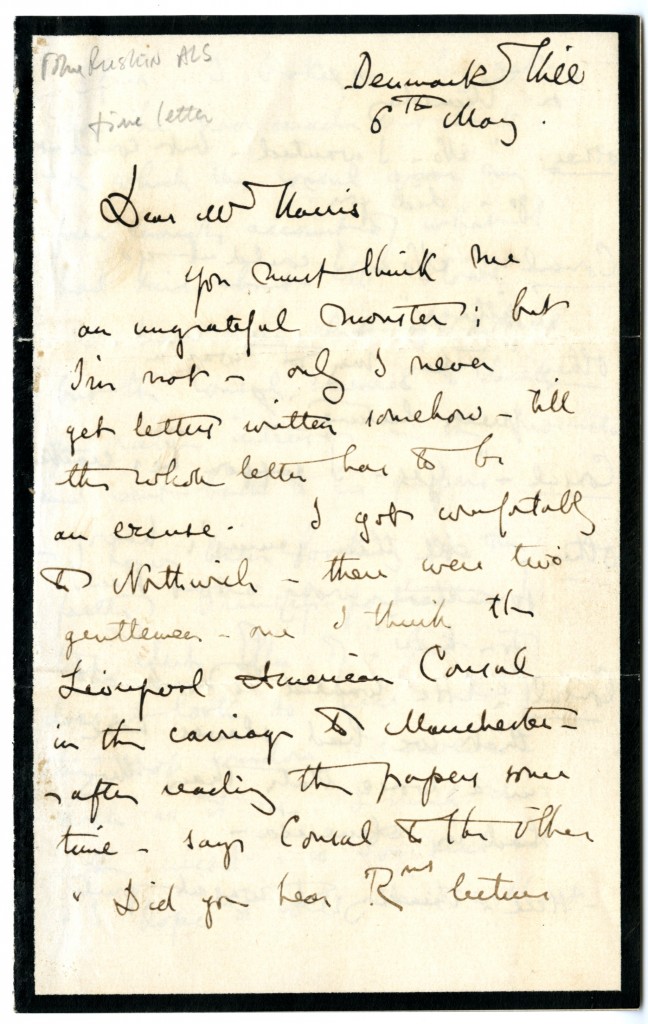

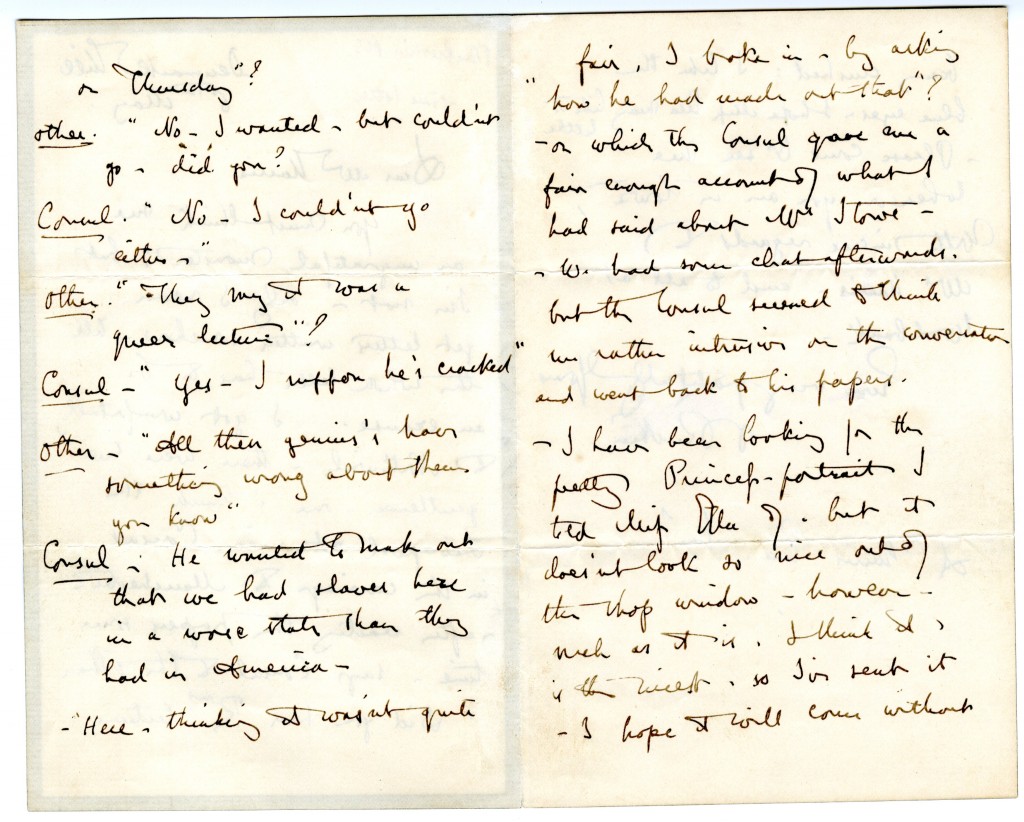

Another fascinating element of the Arnold author collection is the many editions of Arnold’s works that were owned by prominent Victorian writers, for example: a copy of Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy that he presented to Robert Browning; an 1852 edition of Empedocles on Etna, also given to Browning; John Ruskin’s copy of Merope (1858); and Charles Kingsley’s New Poems (1867). Of peculiar interest are the markings made by some of the owners of these volumes – particularly by the latter two – that provide a delightful insight into how they read Arnold’s work. Ruskin, for instance, took issue with Arnold’s preface to Merope (Arnold’s most concerted attempt to revive the art of Greek tragedy in mid-19th century England). Here, Arnold suggests that the role of the chorus in Greek tragedy is merely to summarise, but Ruskin contends that the chorus’s role is autonomous – not reliant on the drama’s action. “[B]ut surely,” Ruskin protests in imaginary debate with Arnold, “the actors were (at least in Sophocles and Aeschylus) dependent on and subordinate to the actions of the chorus. Not vice-versa” (xliii). Shortly afterwards, Ruskin pursues this marginal disagreement with Arnold. Where Arnold writes that the chorus is “the relief and solace in the stress and conflict of the action,” Ruskin comments: “or an uncomfortable spasm of poetic inspiration” (xliv)! Perusing his copy of New Poems, the reader discovers that Kingsley was greatly interested by Empedocles’s prosaic-monotonous monologue atop Etna – a fact to which his highlighting more than a third of its stanzas testifies – but he also loaded the philosophically antithetical “Rugby Chapel” with strokes of his pencil.

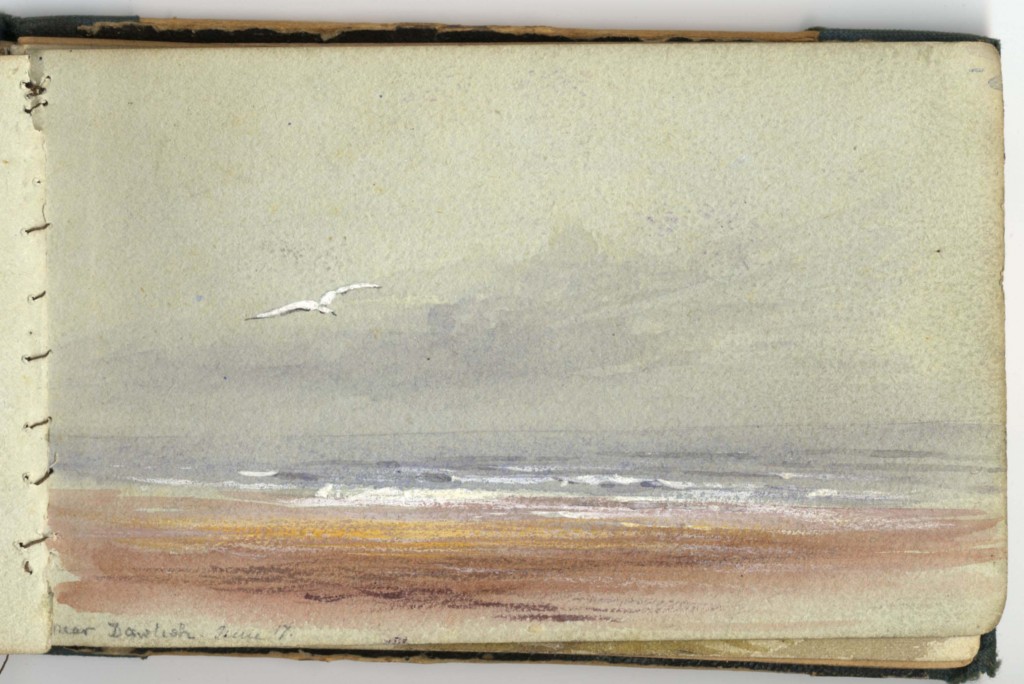

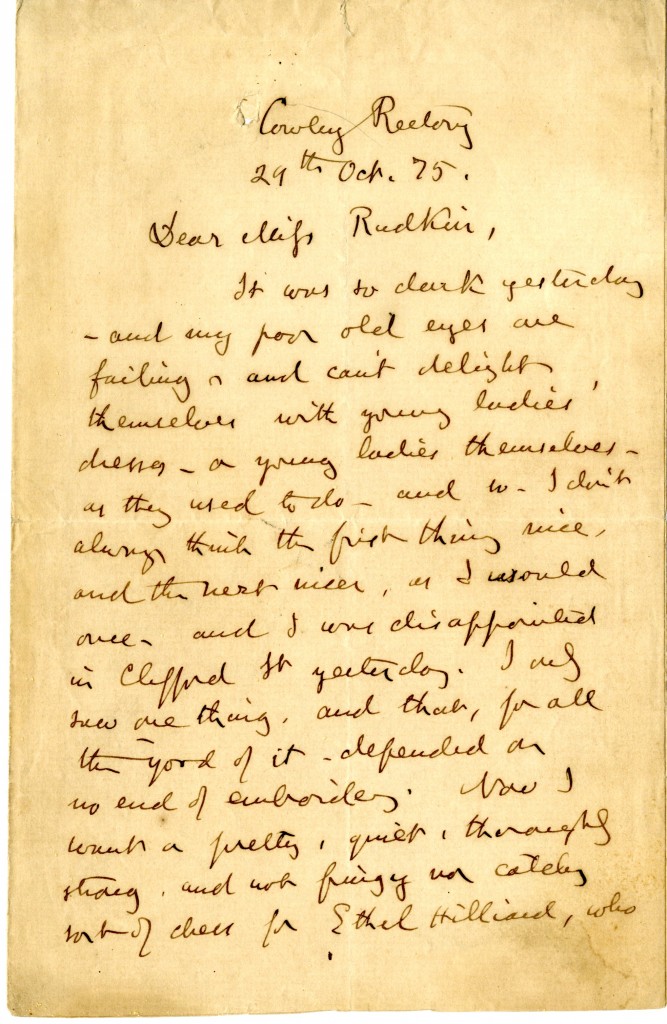

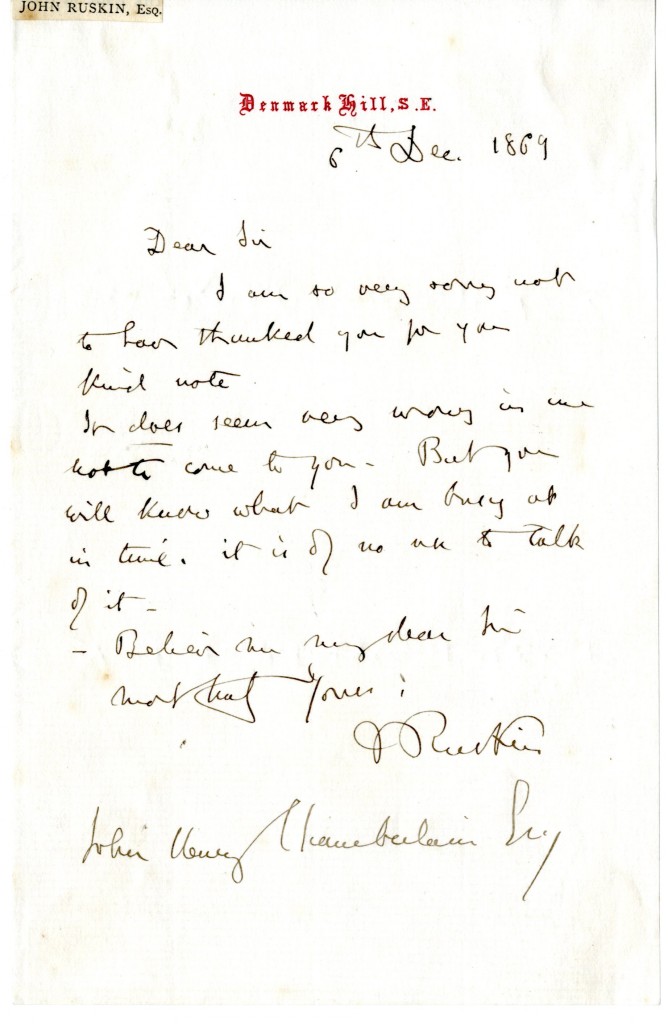

Marginalia by John Ruskin in his copy of Matthew Arnold’s Merope: A Tragedy, London, 1858 (ABLibrary 19thCent PR4022 .M3 1858 c.3)

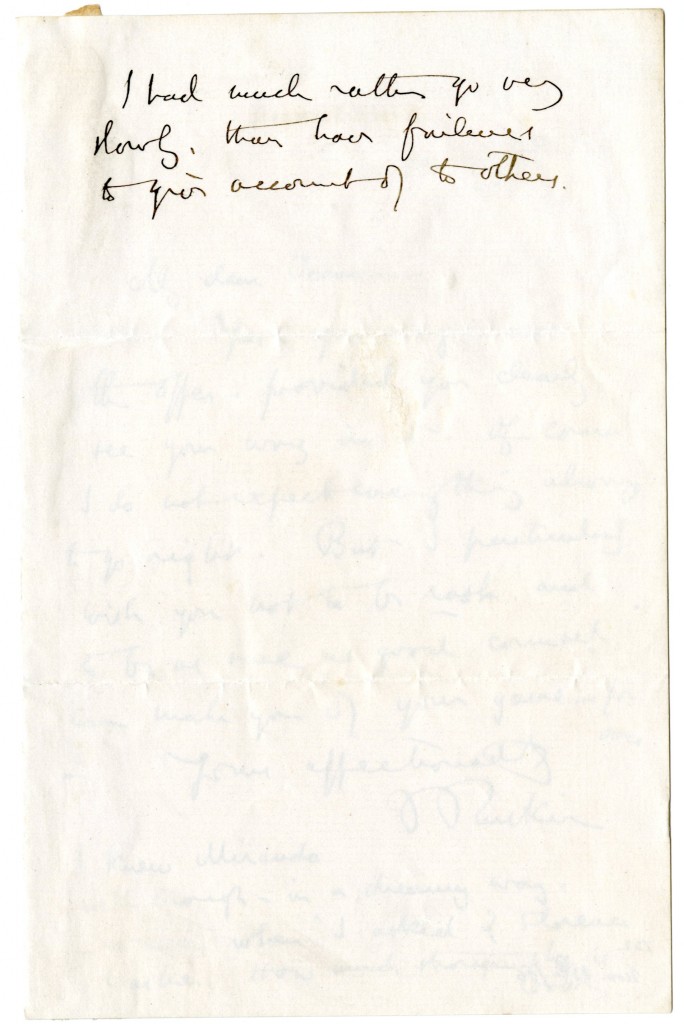

But perhaps the most valuable aspect of the Arnold collection are those 100+ volumes from Arnold’s personal library, which were purchased after the death of his grandson Arnold Whitridge. These were acquired by past ABL director Roger Brooks and include, as Brooks put it in a PR release at the time, “Many of the works [that] were well-known influences upon Arnold during his most formative years as a poet and critic.” Thus, there are editions of Aeschylus’s and Euripides’s tragedies (1843, 1855), Aristotle’s Metaphysics (1848), Arnold’s copy of Madame de Stael’s De L’Allemagne, as well as a number of his volumes on Goethe. While library staff have not yet confirmed that the marks and marginalia were written in Arnold’s hand, Brooks was convinced of it: “[Arnold’s] marginalia, underscoring, and indexing are in many of the volumes along with his well-known book plate,” he writes in the same release. Furthermore, the passages highlighted in these volumes are marked in a manner that is consistent across the books in Arnold’s library and there is a letter in an edition of Poems (1881) held by the library against which his handwriting can be compared. It does, then, seem highly likely that the illuminating “marginalia, underscoring, and indexing” are Arnold’s own.

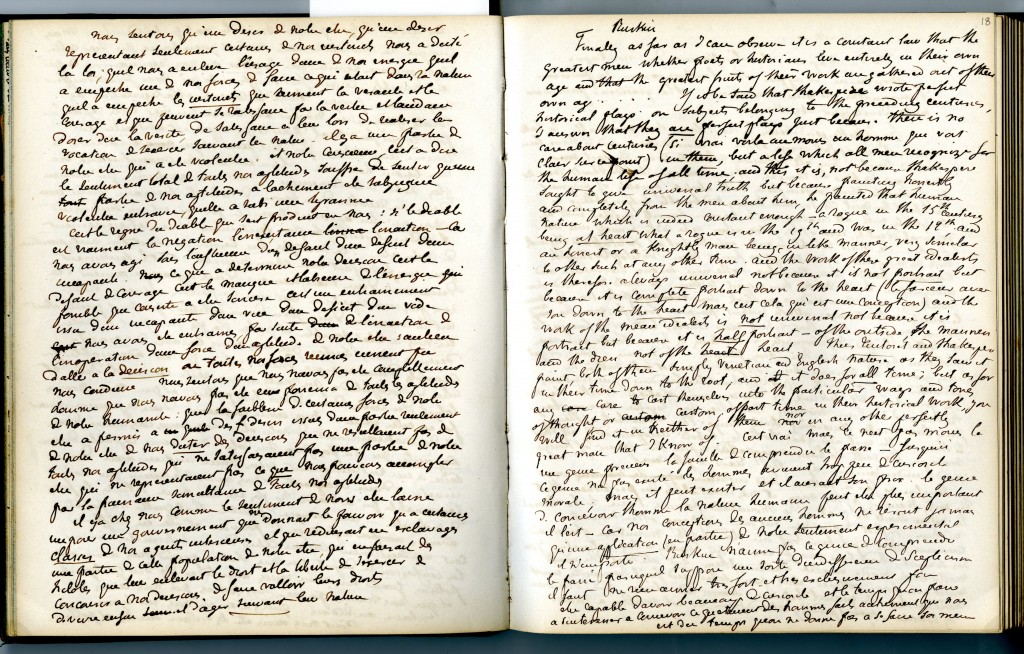

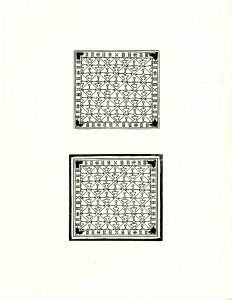

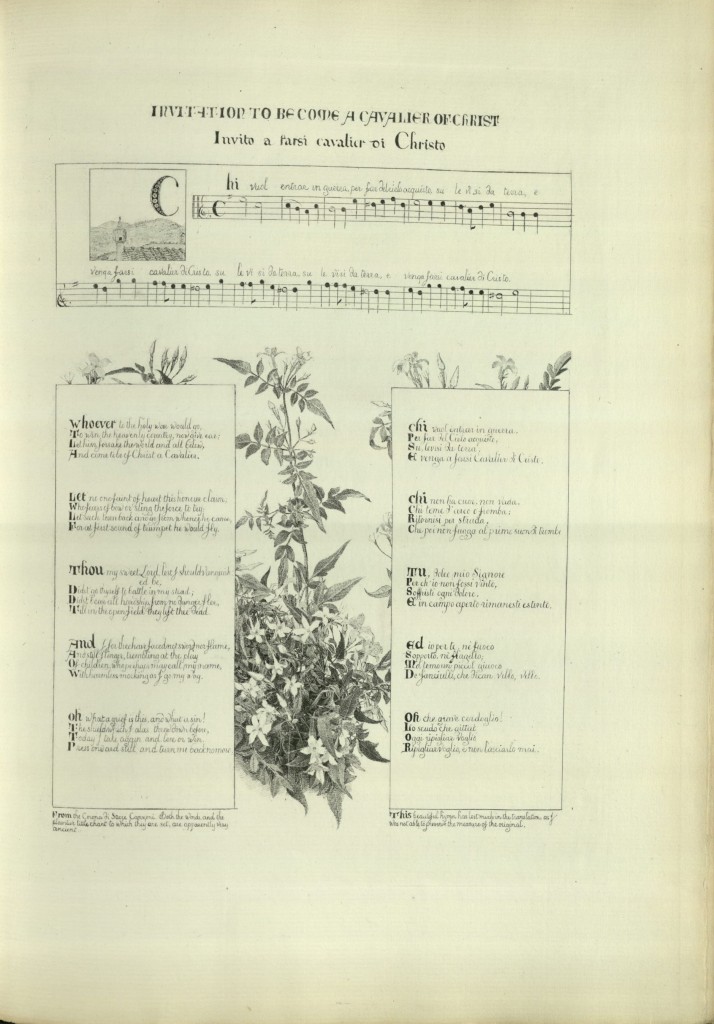

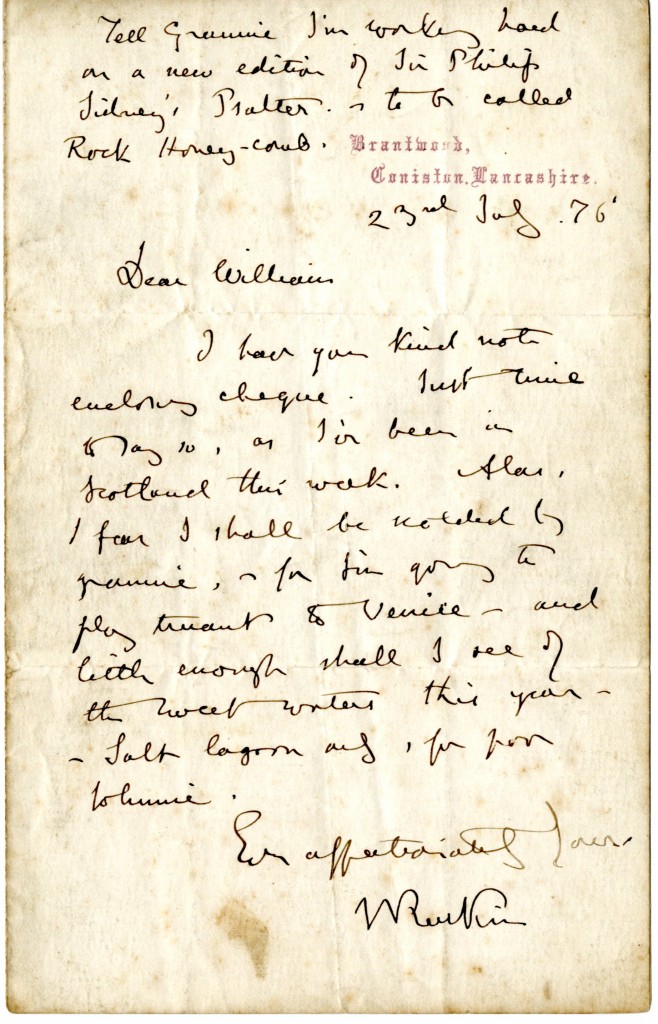

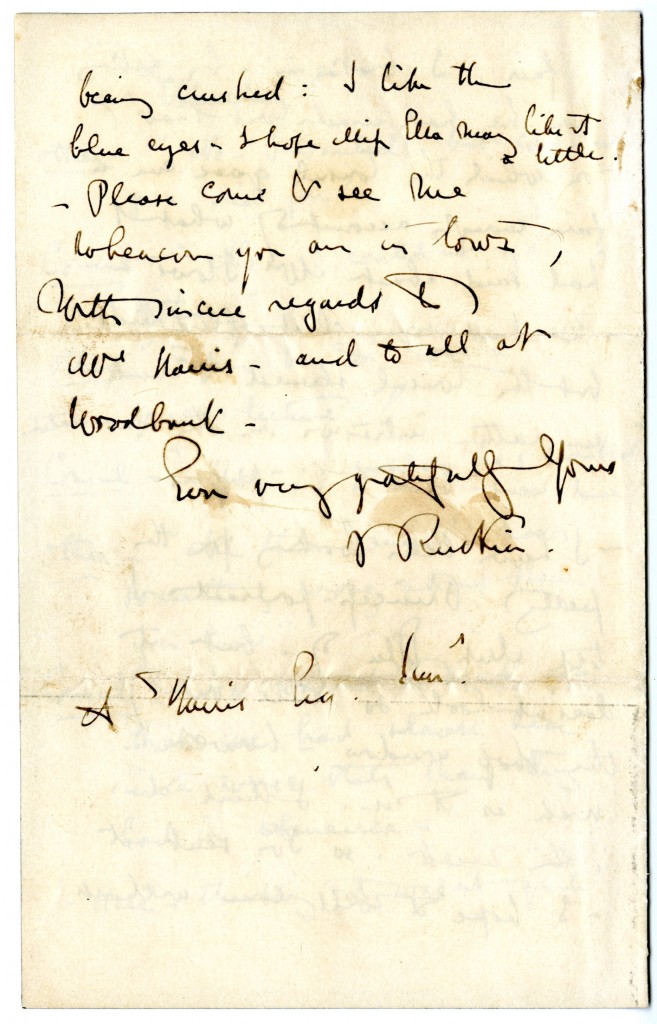

Mathew Arnold’s markings in his copy of J. Barthélemy Saint-Hilaire’s Le Bouddha et sa religion, Paris, 1860 (ABL Matthew Arnold Lib X 294.3 B285b 1860)

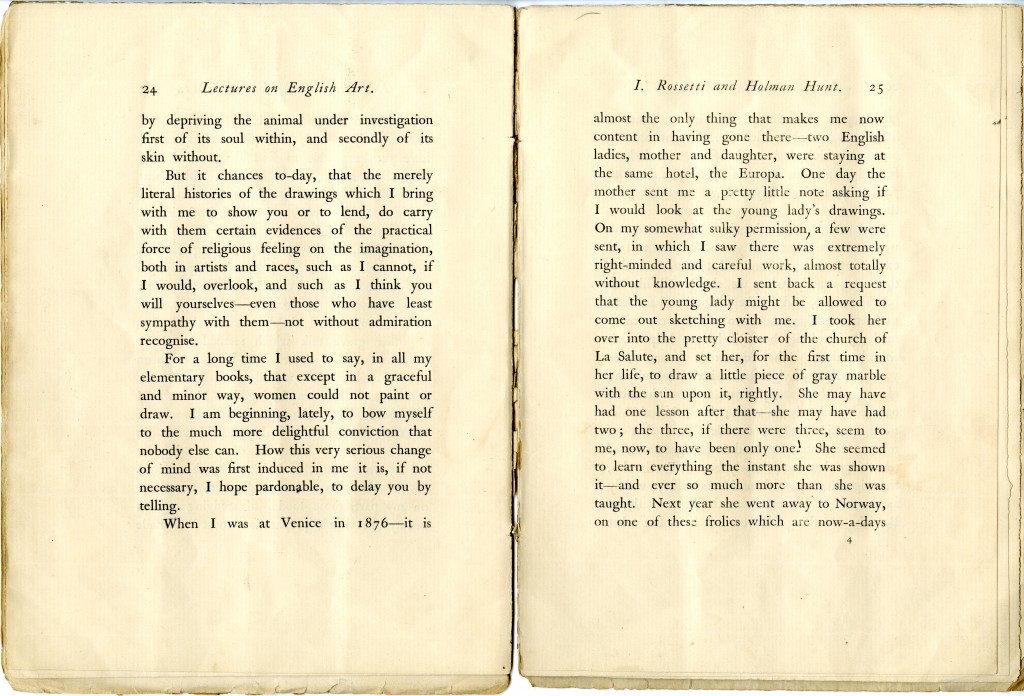

Perhaps the two volumes that were of most interest to my research – in terms of their insight into Arnold’s stoic-pessimism – were his copies of J. Barthélemy Saint-Hilaire’s Le Bouddha et sa religion (1860) and of George Long’s translation of Epictetus: The Discourses of Epictetus; with the Encheiridion and fragments (1877). What particularly struck me about Arnold’s underscoring in Saint-Hilaire’s Le Bouddha was his evident interest both in Siddartha’s emphasis on the abandoning of desire: “la pauvreté et la restrictions des sens” (as Saint-Hilare puts it – 21), and in Siddartha’s insistence on the imperative of sharing the knowledge of “truth” that he has gained with men and women (26). The first element – the abandonment of desire – is reminiscent of Epictetus’s stoic tenant that one should be resigned to whatever happens that is beyond our control. Arnold’s interest in this doctrine of salvation – whether espoused in ancient Eastern thought or in ancient Western thought – is something that he shared with Leopardi. The Romantic Italian poet believed that “pleasure” was an impossible, elusive goal for humans, and that it was better for all of us to confront this bitter truth and to ally ourselves against a cruel and indifferent Nature.

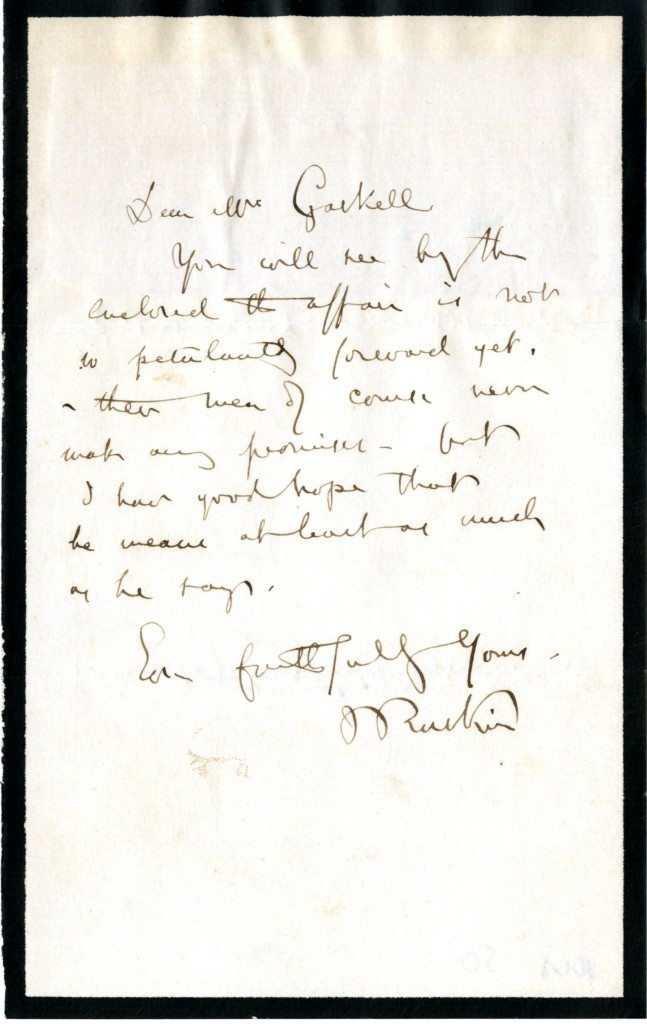

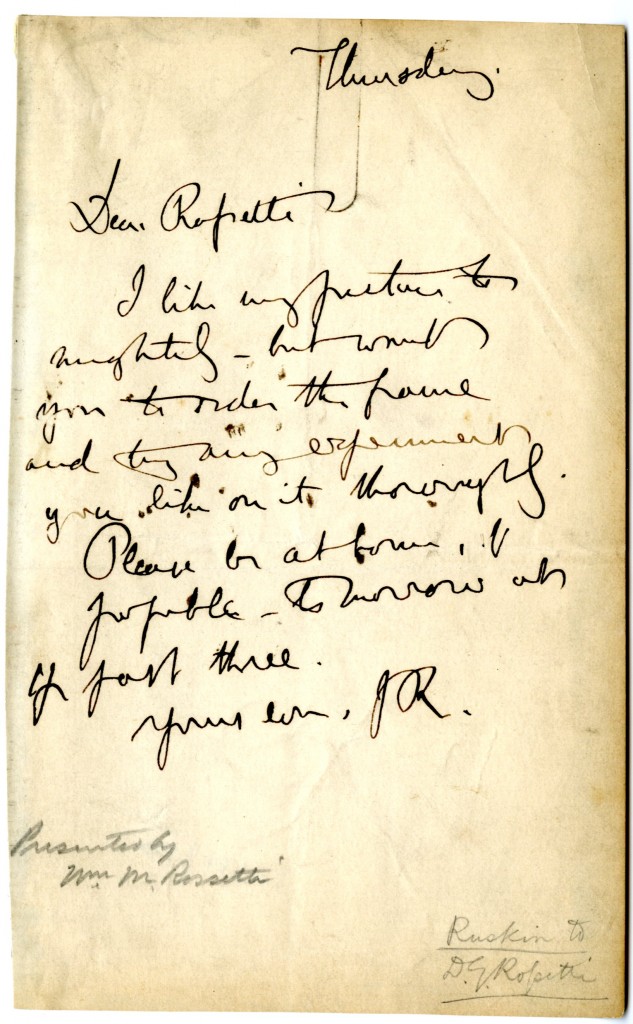

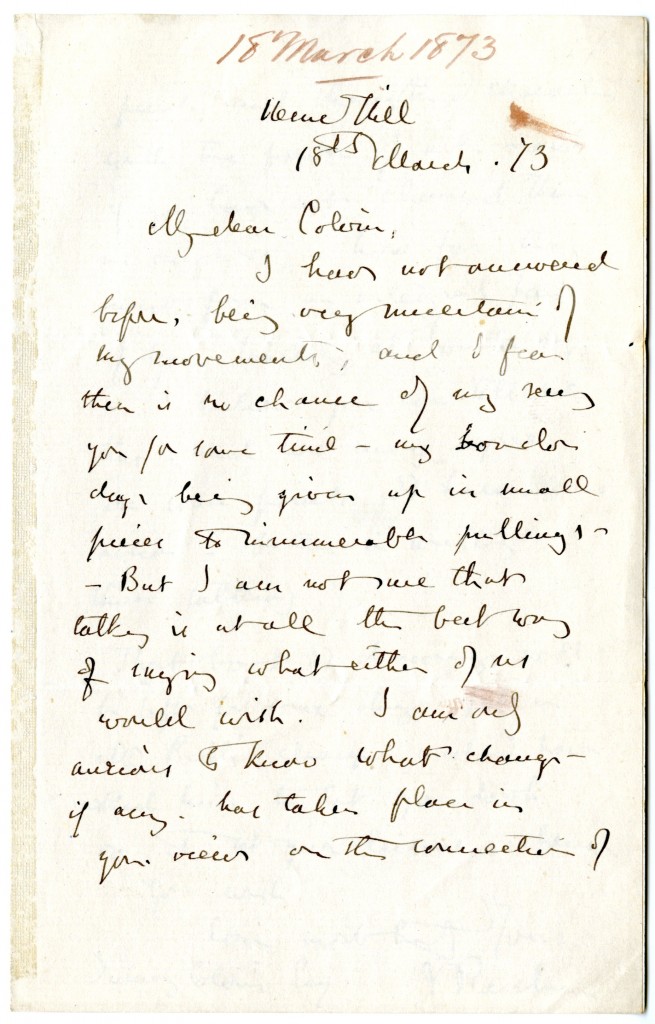

Annotations by Matthew Arnold in his copy of The Discourses of Epictetus, translated by George Long, London, 1877 (ABL Matthew Arnold Lib X 188 E64d 1877 )

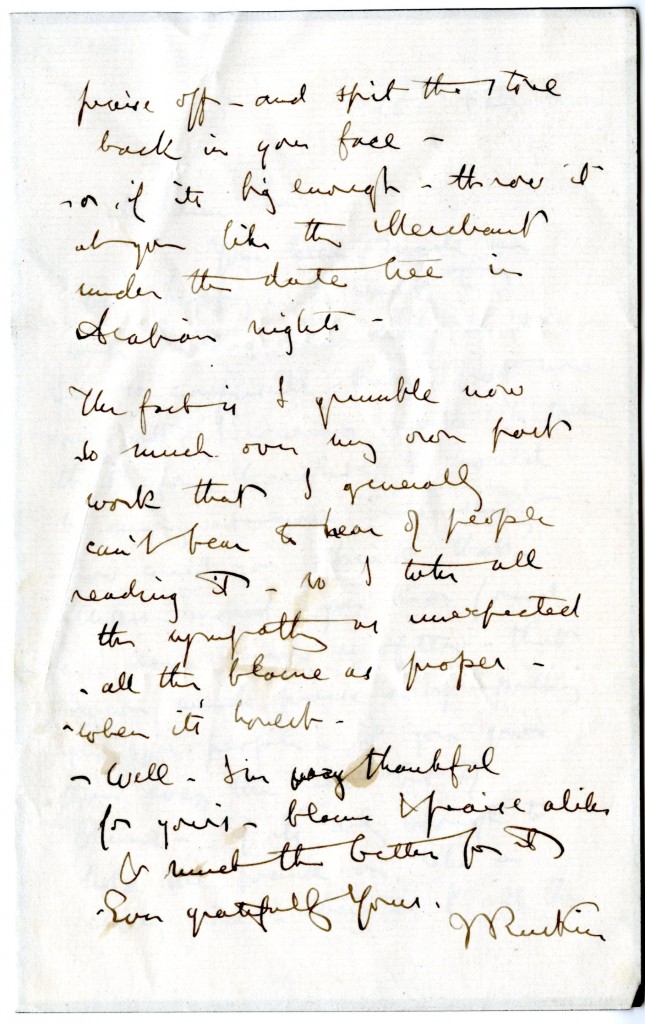

Similar themes in Epictetus appear to be of much interest to Arnold. In the back of Long’s translation, Arnold has noted an index of those elements which, presumably, interested him most, including, enigmatically, the “fallacy.” On following the page references that Arnold includes alongside this term in his text, you realise that he actually has reservations about the stoic doctrine that I outlined (in very broad terms) above. Thus, when Epictetus writes of “learn[ing] to wish that every thing may happen as it does” (1.12.42), Arnold comments in the margin: “fallacy.” Similarly, when Epictetus poses the rhetorical question: “And will you be vexed and discontented with the things established by Zeus, which he with the Moirae (fates) who were present and spinning the thread of your generation, defined and put in order?” (1.12.44), Arnold writes “fallacy.” However, Arnold seems sympathise more with Epictetus when the philosopher suggests that human beings can overcome the desire to control those “things” in their life that are actually beyond their control: “Do you not rather thank the gods that they allowed you to be above these things which they have not placed in your power, and have made you accountable only for those which are in your power?” (1.12.45). Here, Arnold writes: “between the truth and the fallacy,” and one can only wish that he had elaborated a little on what he meant here!

Despite the enigmatic nature of some of Arnold’s comments, tracing his interests through the markings and marginalia that he left behind in these books is a fascinating enterprise, and one that I hope to pursue at a later date.

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-1-zu023x-1024x680.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 2.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-2-1j5hcqf-1024x674.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-3-1bp156v-1024x675.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-4-2f4omtz-1024x674.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-1885-1887-1-1kvnc63-1024x668.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 2.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.1885-1887-2-1kifm1n-1024x678.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.1885-1887-3-21hv1d0-1024x671.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-1885-1887-4-1hkh6d7-1024x652.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison001-1jwdp1q-652x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Pages 2 and 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison002-13paff6-1024x806.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison003-ro19ns-656x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Jane O'Meara] Simon. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Simon001-2kny3fk-686x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Jane O'Meara] Simon. 1 March 1863. Pages 2 and 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Simon002-21yybbs-1024x780.jpg)

![John Ruskin to John Pakenham Stilwell. 14 February [ny].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Stilwell-14-February-ny-1013-y5v810-651x1024.jpg)

![John Ruskin to John Pakenham Stilwell. 14 February [ny].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Stilwell-14-Februaty-ny-2014-2gmvfqu-644x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [William] Kingsley. 18 February 1886. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-William-Kingsley015-1nh5387-658x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to Tom Taylor. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Taylor014-1bq7kpb-673x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Unknown]. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Unk-14a52wp-807x1024.jpg)