By Melinda Creech

Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

The following small group of John Ruskin’s letters are not particularly concerned with art, social issues, or criticism. They focus instead on social engagements, the death of a long-time employee, the design of a dress for a friend, a Christmas wish, and a friend’s memorial, and give us a glimpse into Ruskin’s personal life.

*****

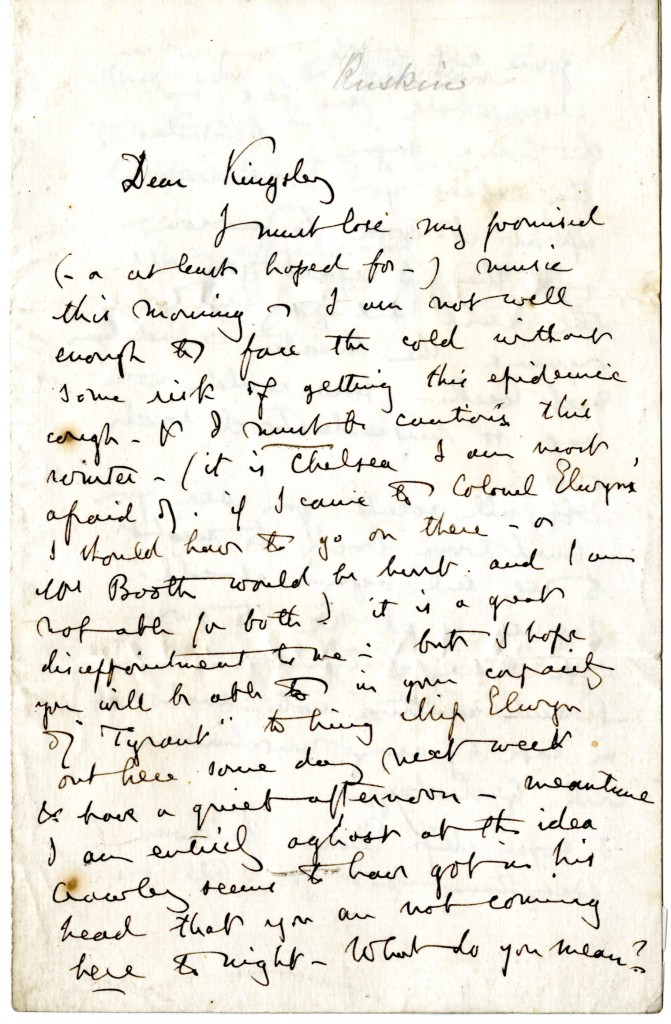

The watermark on this letter suggests this letter to Charles Kingsley, broad church priest of the Church of England, university professor, social reformer, historian and novelist, may have been written around 1862. During that time Kingsley was Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge. A few years later, in 1869, Ruskin would became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford. Both Ruskin and Kingsley were becoming more focused on social issues at this time. Kingsley published The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby, a tale about a chimney sweep in 1863. Ruskin had just published Unto This Last is an essay and book on economy in 1860.

However this letter is much more lighthearted. Ruskin laments missing his hoped for music that morning and engagements at Colonel Elwyn’s and Mr. Booth’s. He chastises Kingsley for not planning to stay with him that evening and informs him that dinner will be at six.

*****

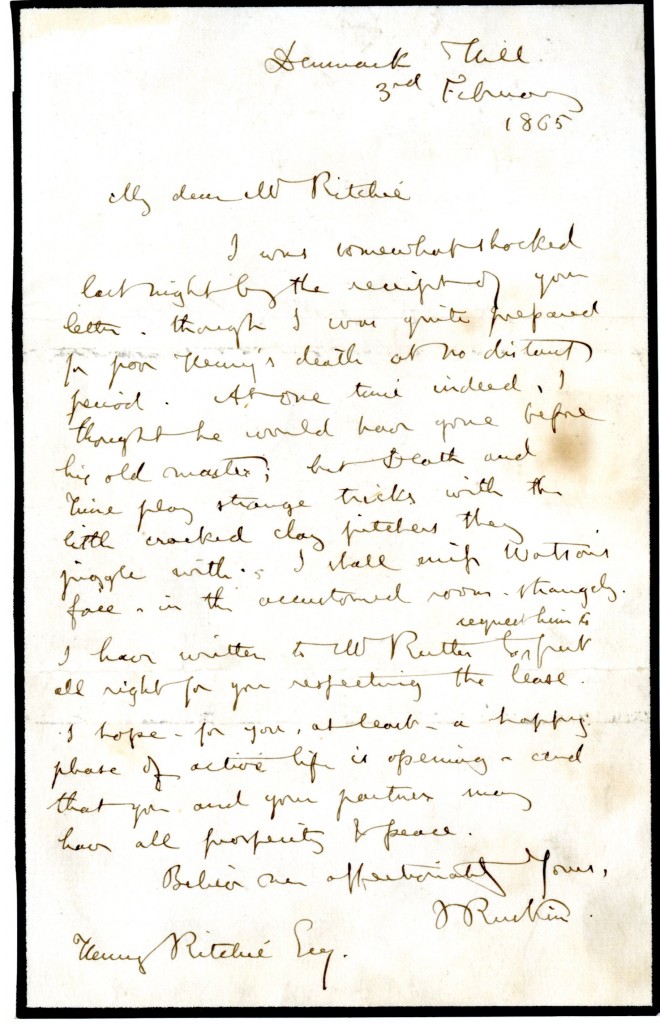

This letter to Henry Ritchie, John James Ruskin’s clerk, expresses Ruskin’s shock at hearing of the death of Henry Watson, his father’s head clerk. Ruskin’s father, who had died the previous year, had been very successful in the wine-importing business, employing two clerks, Henry Watson and Henry Ritchie to assist him with clerical duties. Ruskin says that he expected Watson to have died before his Master, “but Death and Time play strange tricks with the little cracked clay pitchers they juggle with.” Ruskin wishes Ritchie and his new partner “all prosperity & peace.”

*****

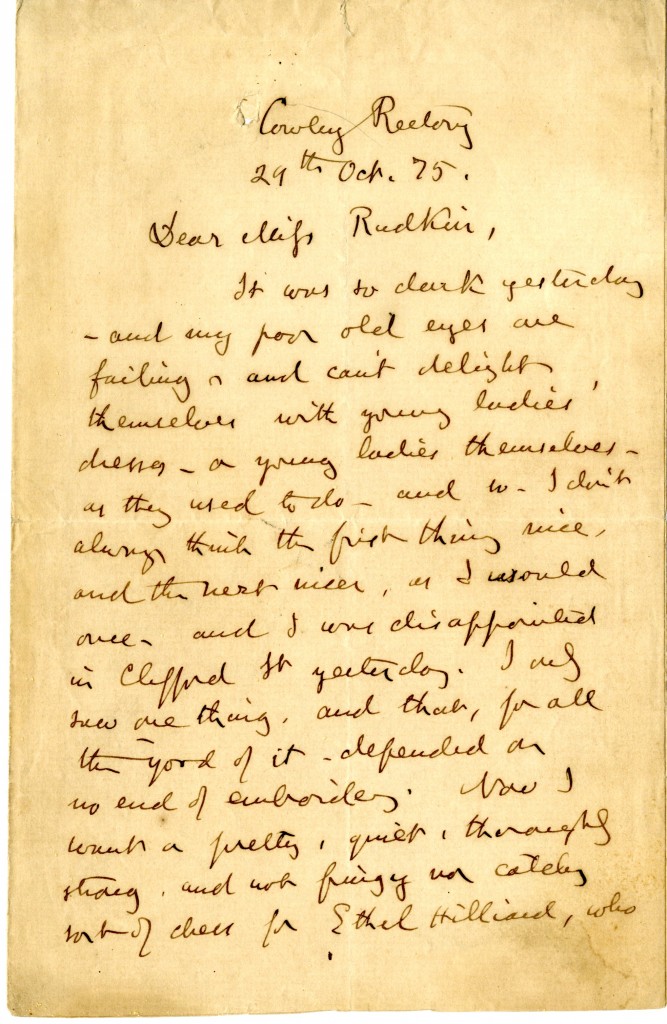

This letter, addressed to Miss Rudkin, expresses a desire to find “a pretty, quiet, thoroughly strong, and not fussy nor catchy sort of dress for Ethel Hilliard,” daughter of Rev. J. C. Hilliard. Ruskin was staying at the Hilliard’s home at Cowley Rectory. He often sought refuge from London at their home. Hilliard’s son, Laurence, became Ruskin’s secretary in the 1870s. We know nothing of Miss Rudkin, other than that Ruskin paid her £14 14s for a silk frock presented to his pet, presumably Ethel Hilliard, on Ruskin’s own birthday, according to Fors Clavigera, Volume VI.

*****

With this letter Ruskin sends a Christmas gift to his cousin Margaret, thankful that he has “been preserved through so grave an illness to see another Christmas.” He expresses the hope that the bright frost in Brantwood “may neither be dark nor unhealthy in London, and that you may yourself have stronger health in the coming year.”

*****

This letter is addressed to Emma Sidney Edwardes, the step-daughter of Dr. Grant, the physician of Ruskin’s father, and wife of Sir Herbert Edwardes, administrator, soldier, and statesman active in the Punjab, India. Her book, paying tribute to her husband’s life, Memorials of the Life and Letters of Major General Sir Herbert Edwardes was published in 1886. In the letter, Ruskin says:

I am so very glad and thankful that book is done. Heaven knows how thankful I shall read every word of it—no wife ever had better right to love her husband to the uttermost—and you have love him, worthily. I think you will be beloved by the way you & he come in gradually in Praeteita.

Emma is described in Chapter 1 of Volume 2 of Praeterita as a nice and clever daughter. On December 22, 1883, Ruskin had delivered as lecture, “The Battle of Kineyree.” The lecture was published as A Knight’s Faith, and two years later, inn 1885, published as A Knight’s Faith : Passages in the Life of Sir Herbert Edwardes, in Bibliotheca Pastorum, Volume 4. Ruskin describes his work in the preface:

The following pages are in substance little more than grouped extracts of some deeply interesting passages in the narrative published by Sir Herbert Edwardes, in 1851, of his military operations in the Punjaub during the winter of 1848–1849 [A Year on the Punjab Frontier]. The vital significance of that campaign was not felt at the time by the British public, nor was the character of the commanding officer rightly understood. This was partly in consequence of his being compelled to encumber his accounts of real facts by extracts from official documents; and partly because his diary could not, in the time at his disposal, be reduced to a clearly arranged and easily intelligible narrative. My own abstract of it… reduced the events preceding the battle of Kineyree [18 June 1848] within the compass of an ordinary lecture, which was given here at Coniston in the winter of 1883; but in preparing this for publication, it seemed to me that in our present relations with Afghanistan, the reader might wish to hear the story in fuller detail, and might perhaps learn some things from it not to his hurt”

Ruskin presented The Edwardes Ruby to the British Museum in honor of Sir Herbert Edwards in 1887. The inscription reads:

The Edwardes Ruby

Presented in 1887 by John Ruskin

‘In Honour of the

Invincible Soldiership

And loving Equity

Of Sir Herbert Edwardes’ Rule

By the Shores of Indus’.

Dear Melinda Creech, Here is a letter from John Ruskin to the Miss Rudkin, mentioned in your account. It is from Brantwood dated 5th April 81. Dear Miss Rudkin I have again to thank you for a great deal of pleasure, which the necessity of my indulgences in these Parisian enchantments , and the graceful and not too costly forms they take under your good taste and judgement make really quite one of my Spring refreshments, like the birds’ nests and blossoms. The ‘Satin Merveilleux’ remains an inexhaustible marvel – but a pang comes across my complacency as I read of the ‘Squirrel’ Muffs; – Not our own poor British Squirrel – I trust? The grey flying things like bats, of America I don’t care about, but I hope you never spoil our forests darlings into muffs – or cuffs – or puffs, or stuffs – ? Everybody is delighted with the general result – and Lily herself not so quite – demoralized – and very happy, believe me, Dear Miss Aleony Rudkin gratefully yours. JRuskin. Comment. I think she was a local dressmaker at Coniston. Two words in the letter Ihasve been unable to make out clearly – the necessity early on may be vexity (?) and the word Aleony I can’t quite make out either. He may have added a first name. It is a typical flattering letter that turns into fantasy – the American bats bit, at least.. I have transcribed hundreds of Ruskin letters, and commented on them, for the Ruskin Collection at the Archive of Modern Conflict in London. I am not quite sure of Lily – I should know. Anyway, I thought you might be interested in this – it had been mislaid. I am called Ian Jeffrey, and I am an art historian (experienced art historian). If you have anything else on Miss Rudkin let me know. We might have some other letters. I am about to transcribe a letter from JR to a circus performer called Tiny White – a lady – utterly unknown, as far as I can see. I hope this reaches you through your institution’s many safeguards. Ian Jeffrey

,