By Melinda Creech

Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

In addition to his importance as an art critic, Ruskin was also a prominent social thinker and philanthropist. The Armstrong Browning Library owns several letters from Ruskin to correspondents who shared his social and political concerns.

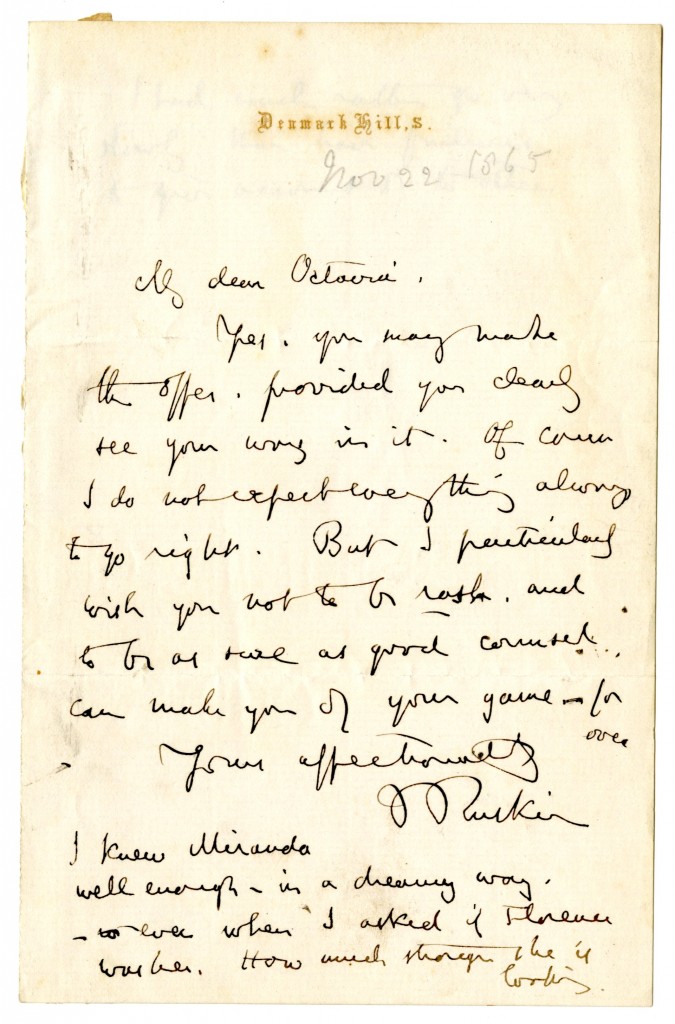

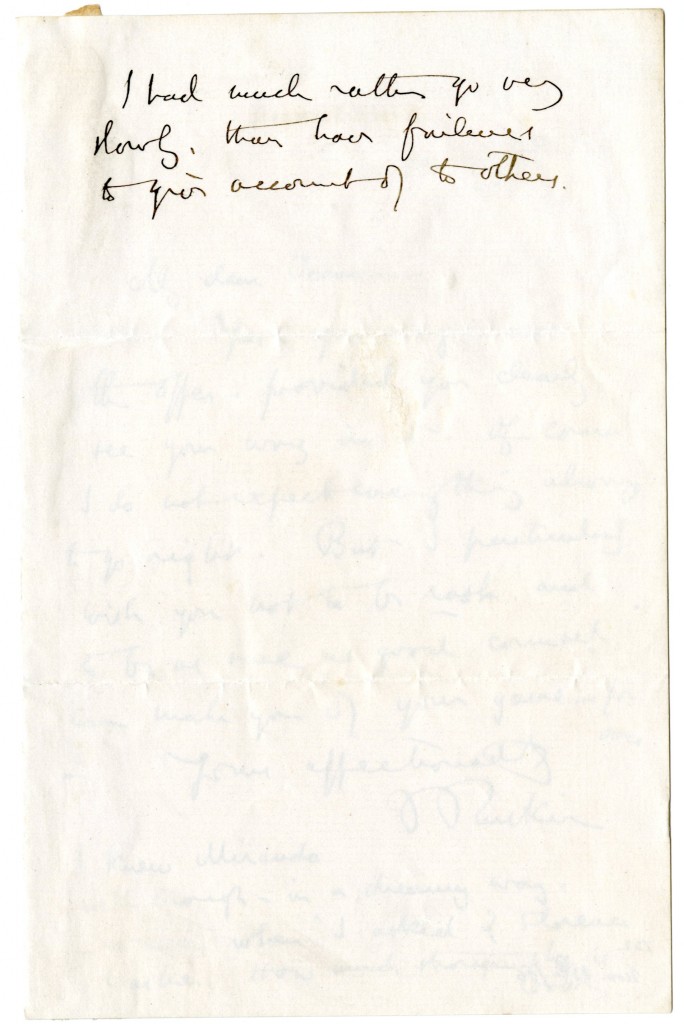

In this letter to Octavia Hill, artist and social reformer, Ruskin gives his permission for Hill to “make her offer.” He warns her “not to be rash and to be as sure as good counsel can make you of your game,” advising her that he “had much rather go very slowly, than have failures to your account or to others.” Based on the date of the letter, Ruskin is probably referring to his lease of three houses of six rooms each in Paradise Place, Marylebone as residences for the poorest of the working class. Ruskin placed these houses under the management of Hill, who had a deep concern for housing for the poor.

*****

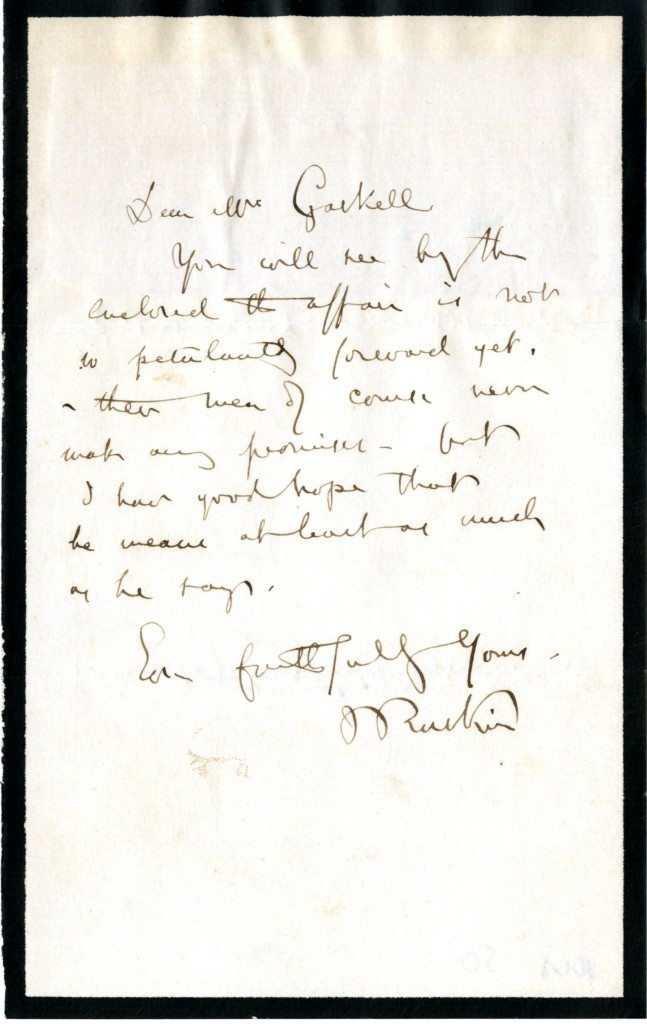

This letter from John Ruskin to Elizabeth Gaskell, English novelist and short story writer, is likely a response to Gaskell’s letter of February 1865. In that letter Gaskell asked Ruskin to pull whatever political strings that he could to make sure that her friend, Alfred Waterhouse, architect of the Assize Courts, had his name among those to be considered as architects for the new Law Courts in London, a position to be appointed by William Cowper. The appointment was prolonged and contentious. The judges wanted George Edmund Street to design the exterior, with the interior designed by Charles Barry. A special committee of lawyers favored Alfred Waterhouse’s designs, Elizabeth Gaskell’s choice. The appointment was eventually won by George Edmund Street, who died in 1881 before the project was completed. This letter suggests that Ruskin had contacted William Cowper and was able to assure Gaskell, “you will see by the enclosed the affair is not so petulantly forward yet, then men of course never make any promises—but I have good hope that he means at least as much as he says.”

*****

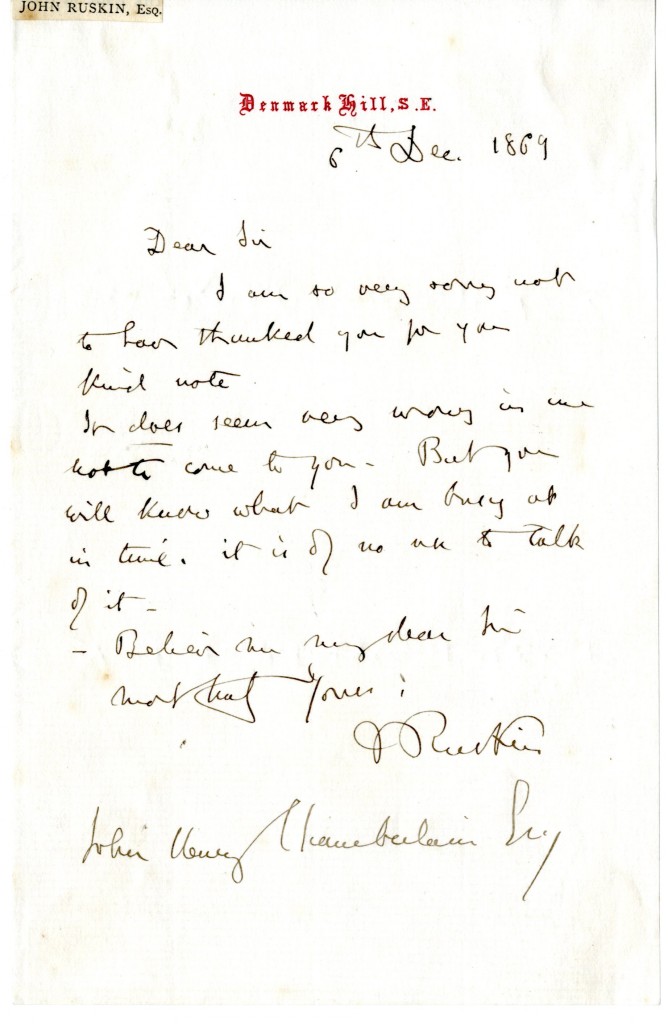

Ruskin apologizes for not thanking John Henry Chamberlain, architect from Birmingham, for his kind note. Ruskin later chooses Chamberlain to be a trustee of St. George’s Guild. St. George’s Guild is an Educational Trust created by John Ruskin to oppose modern, industrial capitalism and the ugliness, poverty, and pollution it produced. He hoped to establish communities that would oppose profit-driven industry and provide alternatives to mass production.

*****

The Armstrong Browning Library also owns eight letters of correspondence between Ruskin to John Pakenham Stilwell, British banker, Navy Agent, and Chairman of the Board of Management of the London Homeopathic Hospital. In the letters Ruskin thanks Stilwell for his gifts to St. George’s Guild and apologizes for his mistakes in accounting. In this letter Ruskin laments the plight of the poor:

I am truly helped by your kind letter, and entirely feel with you as to the quantity of good heart left in England. But as far as I have seen in history the innocent suffer with the guilty . . . . And when Revolution comes, as it must, distress will be everywhere.

*****

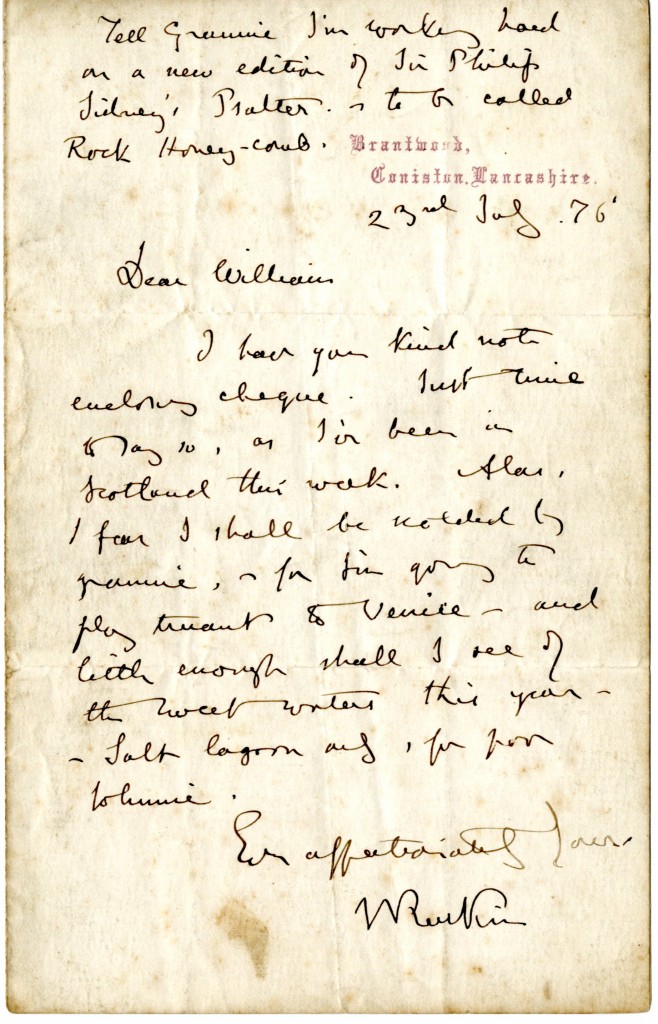

Ruskin had appointed William Cowper-Temple, a British Liberal Party statesman and politician and family friend, as trustee for St. George’s Guild. In this letter he thanks Cowper-Temple for his note and cheque. “Grannie,” referred to in the letter, is Lady Georgiana Cowper-Temple. He variously addressed her as “Phile,” “Isola,” “Mama,” and “Grannie.” In the letter Ruskin tells William to tell Grannie he is working on an edition of Sir Philip Sidney’s psalter, which was published the next year as Rock Honeycomb: Broken Pieces of Sir Philip Sidney’s Psalter. Laid Up in Store for English Homes. Ellis and White, 1877.

![John Ruskin to John Pakenham Stilwell. 14 February [ny].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Stilwell-14-February-ny-1013-y5v810-651x1024.jpg)

![John Ruskin to John Pakenham Stilwell. 14 February [ny].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Stilwell-14-Februaty-ny-2014-2gmvfqu-644x1024.jpg)