By Melinda Creech

Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

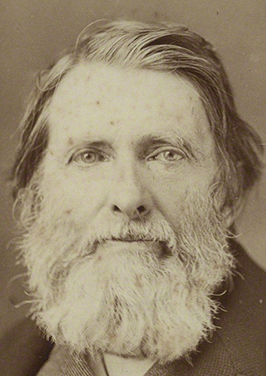

The Armstrong Browning Library holds twelve letters recounting the correspondence between John Ruskin and the Brownings.

The earliest, [16 October 1855], is a letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Ruskin apologizing to him for not being able to see him before they leave for Paris.

In his letter to Ruskin of [1 February 1856], Robert Browning discusses Modern Painters.

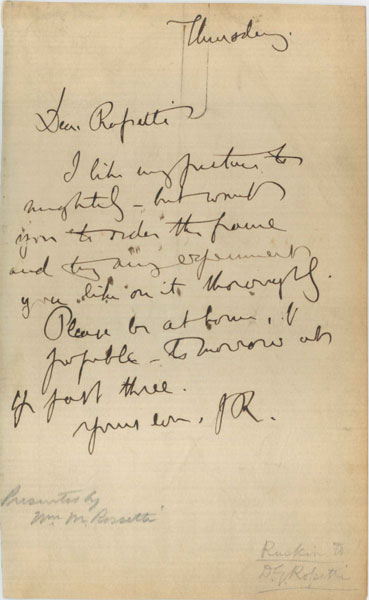

In Ruskin’s letter to Robert Browning of 29 August 1856, he apologizes for “mangling” Browning’s “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church” in Modern Painters and describes his tired, “vegetative” state.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning writes to John Ruskin’s mother on 18 October 1856, thanking her for her gifts of a netted scarf, flowers, and a box of preserves. Elizabeth also thanks her for her attention to her son Pen and for reading his poems that Elizabeth had sent to Mrs. Ruskin.

John Ruskin replies to Elizabeth on 18 October 1856, saying that he intends to send a gift to Pen. He also talks about his admiration for the poetry of both Brownings.

In a letter of 3 June 1859, Elizabeth recommends an artist, Mr. Page, to Ruskin. She also thanks Ruskin for speaking kindly about Italy, whose political situation is not looked on favorably by many people in England.

Robert informs Ruskin in a letter of [Mid-May 1862] that he will be at the National Gallery under the Portico of the Entrance to the Old Masters on Friday at five and hopes to have tea with him.

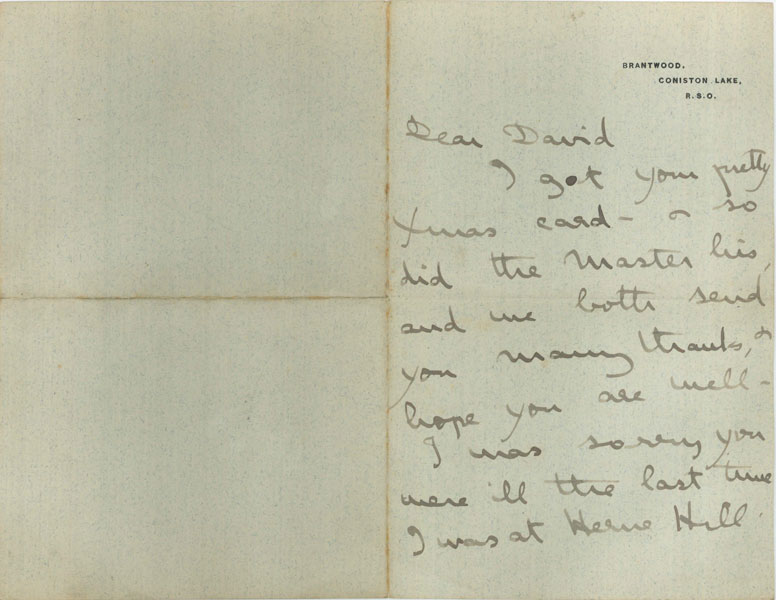

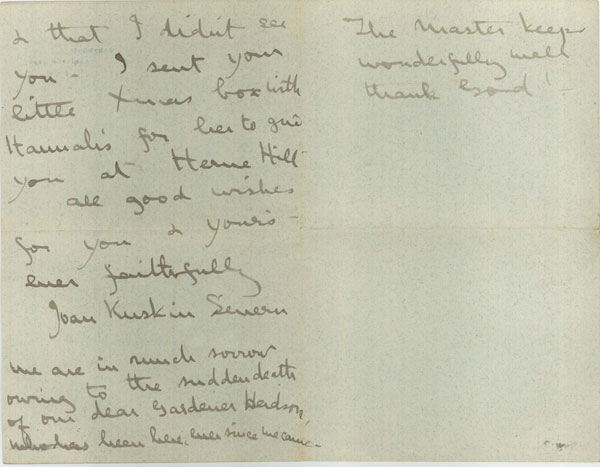

Ruskin mentions to Mrs. Johnson in a letter of [31 January 1865] that he has not written to Browning for a long time. He writes, rather cryptically: “Leave granted at once by Browning. I had not written to him for a long time and had to tell him why, and couldn’t at the time your letter came.”

The Armstrong Browning Library holds an envelope from Ruskin to Browning, 6 February 1865. The letter, which invites Browning to dinner at five on Wednesday, is located at The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

In this letter, [26 March 1866], Browning regrets he cannot accept Ruskin’s invitation.

Browning invites Ruskin to view Pen’s paintings in this letter of 28 March 1880.

In this letter of 12 August 1884 Browning forwards a letter from Mrs. Bloomfield Moore, author and art collector, to Ruskin.

In addition to these letters The Browning Letters project provides access to twenty Ruskin letters held by the Ransom Center at the University of Texas and three letters from Special Collection at the Margaret Clapp Library at Wellesley College. There are thirty-four references to John Ruskin in The Browning Letters.

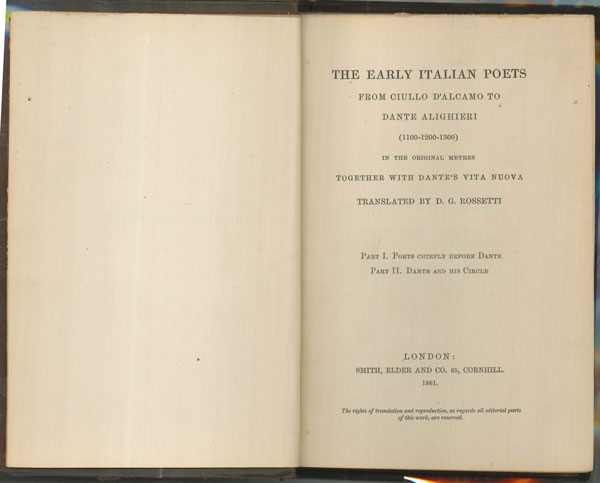

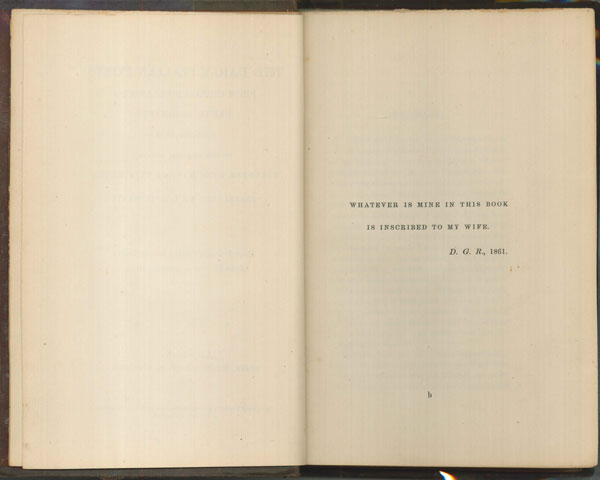

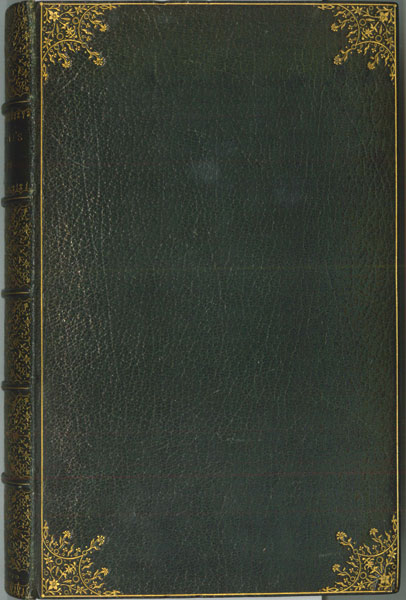

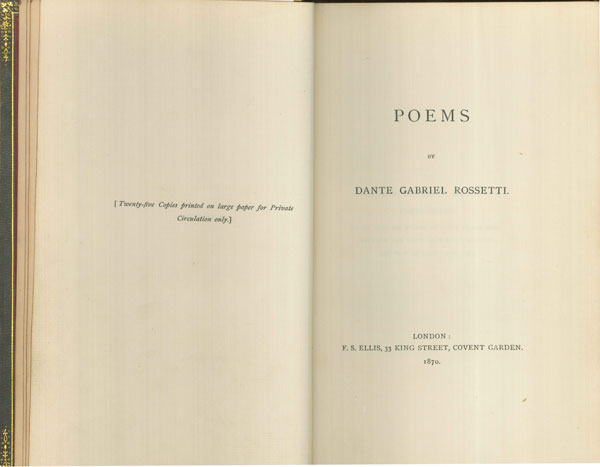

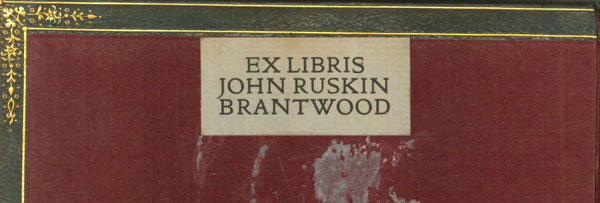

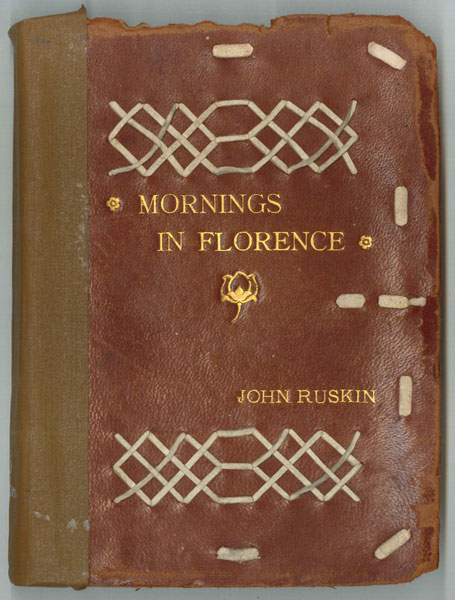

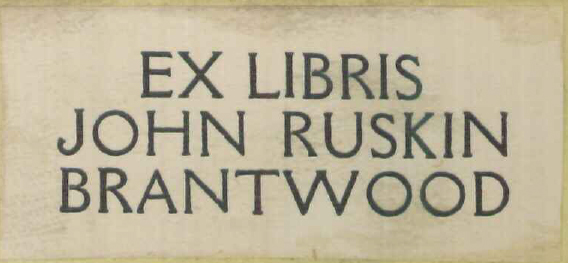

Among the items in the John Ruskin Collection at the ABL are Ruskin’s copies of the Brownings’ works. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s The Greek Christian Poets and the English Poets bears Ruskin’s bookplate: “Ex Libris/John Ruskin/Brantwood.” Robert Browning’s translation of The Agamemnon of Aeschylus bears the same bookplate.

John Ruskin’s bookplate in Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The Greek Christian Poets and the English Poets. London: Chapman & Hall, 1863.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The Greek Christian Poets and the English Poets. London: Chapman & Hall, 1863.

Ruskin’s copy of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Greek Christian Poets contains an annotation regarding the provenance of the book, indicating that Dr. and Mrs. Armstrong secured the book from Ruskin’s Coniston House.

Ruskin’s copy of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Greek Christian Poets contains an annotation regarding the provenance of the book, indicating that Dr. and Mrs. Armstrong secured the book from Ruskin’s Coniston House.

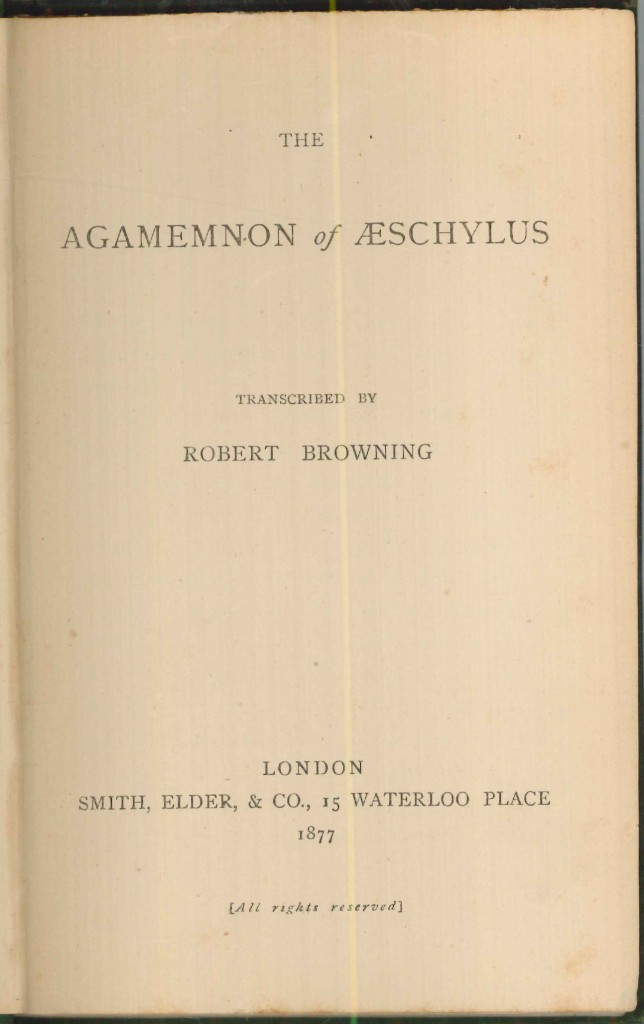

John Ruskin’s bookplate in Aeschylus. The Agamemnon of Aeschylus, Transcribed by Robert Browning. London: Smith Elder & Co., 1877.

Aeschylus. The Agamemnon of Aeschylus, Transcribed by Robert Browning. London: Smith Elder & Co., 1877.

In a letter to Miss Carrie, 15 June 1914, Mrs. Lilian Whiting, an American journalist and biographer of the Brownings, relates this story recalled by Pen Browning about his father and John Ruskin.

Some six years before Mr. Barrett Brofning’s [sic] death (in July of 1912) he bought one of the old Medici villas that are scattered about Tuscany, , one called “La Torre All’ Antella”, about five miles out of Florence, and began “restoring” it. (That was his favorite amusement, and contributed largely to his dying a hundred and fifty thousand dollars in debt.) But to the last he had only two rooms that were habitable, and in those he camped out, so to speak, the rest of the house being in the hands of workmen. It was left in a totally unfinished state. In an outhouse he had packed all the furniture. He took me into the storehouse to see it, – the sofa, as high as a catafalque, on which he remembered seeing his father and Ruskin sitting side by side, with their feet dangling.

Robert Browning’s snuff box of Georgian silver is a crescent-shaped, engine turned box made in Birmingham in 1797 with R. B. monogrammed on the lid. It was reputedly given by Browning’s daughter-in-law, Fannie Coddington Browning, to John Ruskin and was still in his possession at his death in 1900.

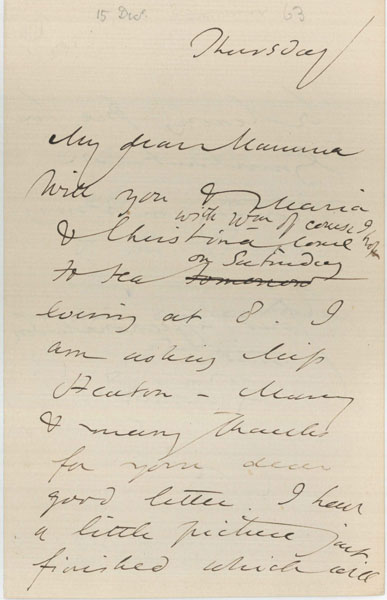

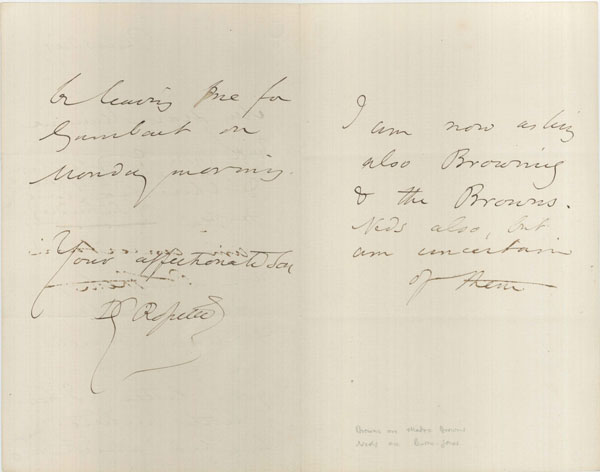

![John Ruskin to Mrs. Johnson. [31 January 1865].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Johnson-1-16kewxa-641x1024.jpg)