By Melinda Creech

Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

The article, “Women Artists in Ruskin’s Circle,” written by Jane Garnett, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography continues:

The other woman discussed by Ruskin [in the first Slade Lecture], (Isabella) Lilias Trotter (1853–1928), was completely unknown, and was not an artist by profession but a committed evangelical, at that point working for the YWCA in London. She was born on 14 July 1853 at Devonshire Place House, Marylebone, the seventh child of Alexander Trotter (1814–1866) of Dreghorn, Midlothian, a businessman, and the eldest of his second wife, Isabella Strange. She was educated at home in London by French and German governesses and was encouraged by her father in scientific and artistic pursuits; in the summer the family travelled on the continent. After the death of her father in 1866, she developed a new seriousness, and in the mid-1870s she attended with her mother evangelical conventions at Broadlands and Oxford; she sang in a choir during the Moody and Sankey revival of 1875. It was on a visit to Venice in October 1876 that she met Ruskin. Discovering that Ruskin was staying at the same hotel, her mother asked whether she could show him some of her daughter’s watercolours. As Ruskin recounted in the Slade lecture: ‘I saw there was extremely right-minded and careful work, almost totally without knowledge. I sent back a request that the young lady might be permitted to come out sketching with me.’ He commented on her learning ‘everything the instant that she was shown it—and ever so much more than she was taught’, and went on to display her drawings of peasant life in Norway, commended for conveying the same attributes of Christian simplicity which Francesca Alexander was doing in Tuscany (Complete Works, 33.280–81). Her Norwegian notebooks were to form part of Ruskin’s gift to the University of Oxford. She visited Brantwood regularly with her brother and sometimes her sister, and drew under Ruskin’s encouragement. But in 1879 she was to decide that she could not commit herself to painting ‘in the way he means, and continue still to “seek first the Kingdom of God and His righteousness”’ (Stewart, 19). She worked for the YWCA, took a Bible class at the Welbeck Institute, and began to hold meetings at her own home in Montagu Square for women in the business houses of Oxford and Regent streets. In 1886 she bought a nightclub to convert into a restaurant for such women; and she worked at night among prostitutes. She continued to paint and to send sketches to Ruskin, who felt, however, that her work was deteriorating:

The power in these drawings is greater than ever—the capacity infinite in the things that none can teach; but the sense of colour is gradually getting debased under the conditions of your life … Technically you are losing yourself for want of study of the great colour masters. (ibid., 22–3)

In 1888 Trotter went to Algeria as a missionary, where she worked until her death, publishing Arabic translations of the gospels and organizing conferences for the missionaries of north Africa. At the same time she responded passionately both as an artist and as an evangelical to the landscape and colours of Algeria. Fascinated by the vivid sapphire blue of Kabylian berries growing deep under matted grass, she tried to paint them ‘to show what God can do with the very feeblest ray; but the blue is an unattainable colour’ (Master of the Impossible, 19). In 1926 she published a little story, Focussed, written for the YWCA, in which she used a similar image of a dandelion, catching a shaft of sun in a dark wood: from this she developed the metaphor of the lens to press the need for everyone to choose on what to focus and not to dissipate energy. Her aesthetic comments on detail and line, in Africa and on trips in Switzerland and north Italy, continued to show a strong Ruskinian sensibility. Until her death she sent watercolours of people, places, and plants—often in a bold and independent style—to him among others. She died in Algiers on 27 August 1928.

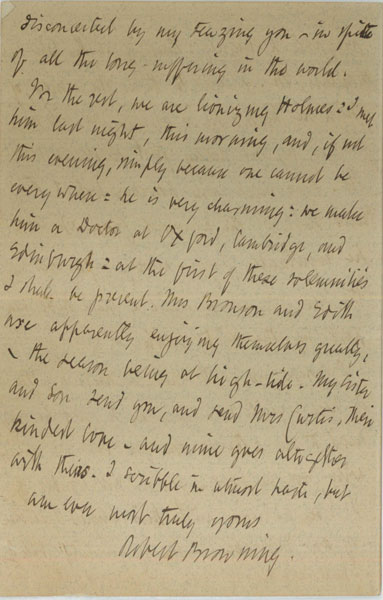

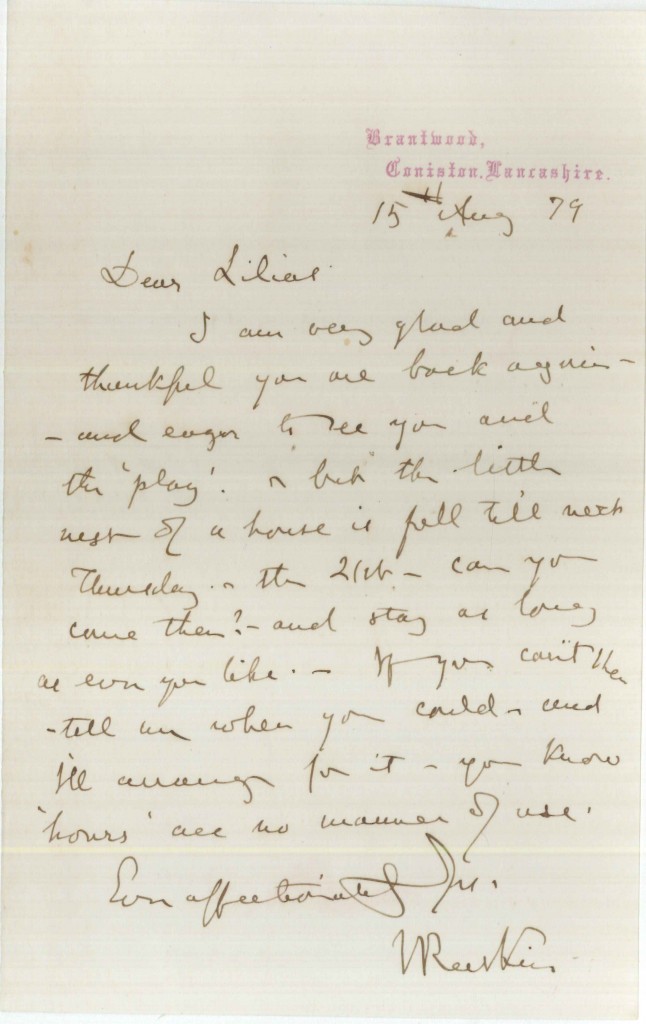

The Armstrong Browning Library owns one letter from John Ruskin to Lilias Trotter.

Letter from John Ruskin to Lilias Trotter. 15 August 1879.

In this letter, Ruskin invites Lilias to come to Brantwood on Thursday, the 21st.

I am very glad and thankful you are back again—and eager to see you and the ‘play’.—but the little nest of a house is full till next Thursday—the 21st—can you come then?—and stay as long as ever you like.—If you can’t then tell me when you could—and I’ll arrange for it—you know ‘hours’ are no manner of use.

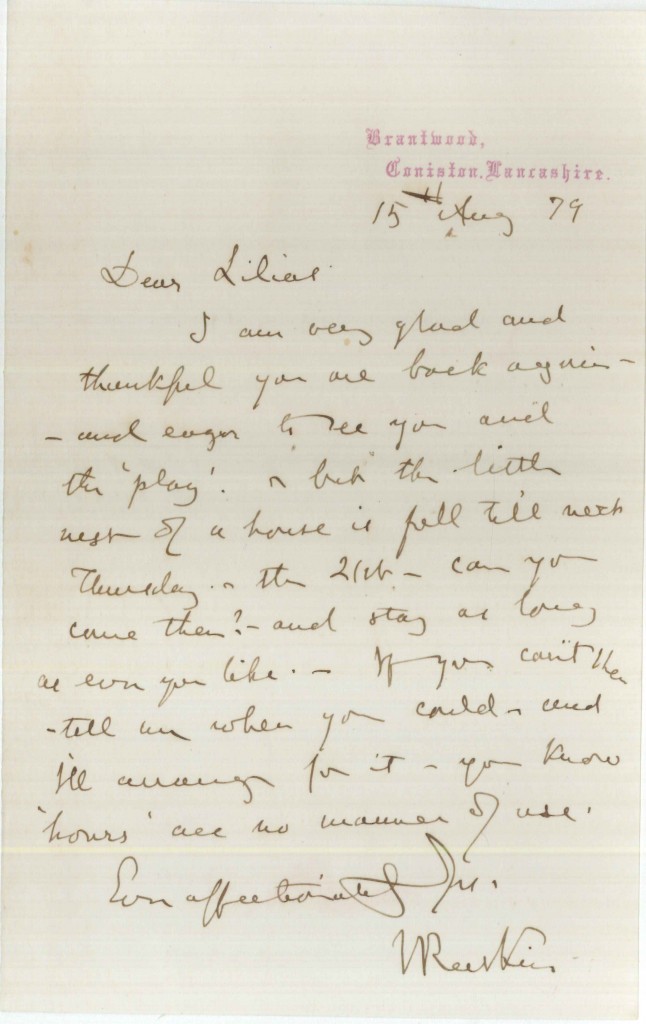

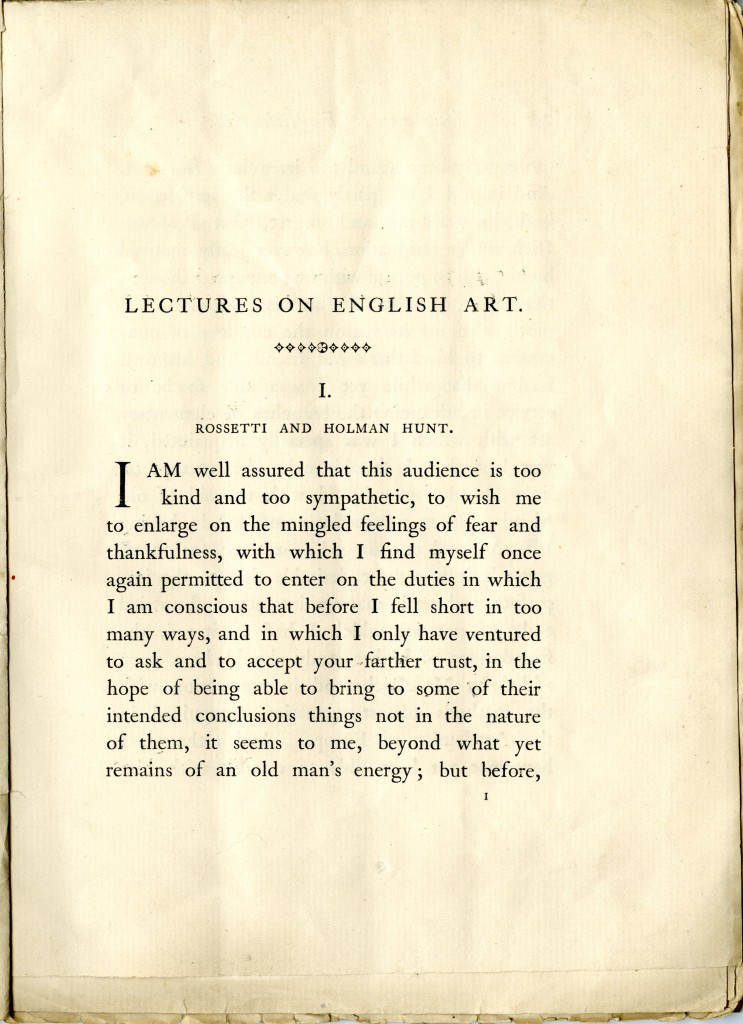

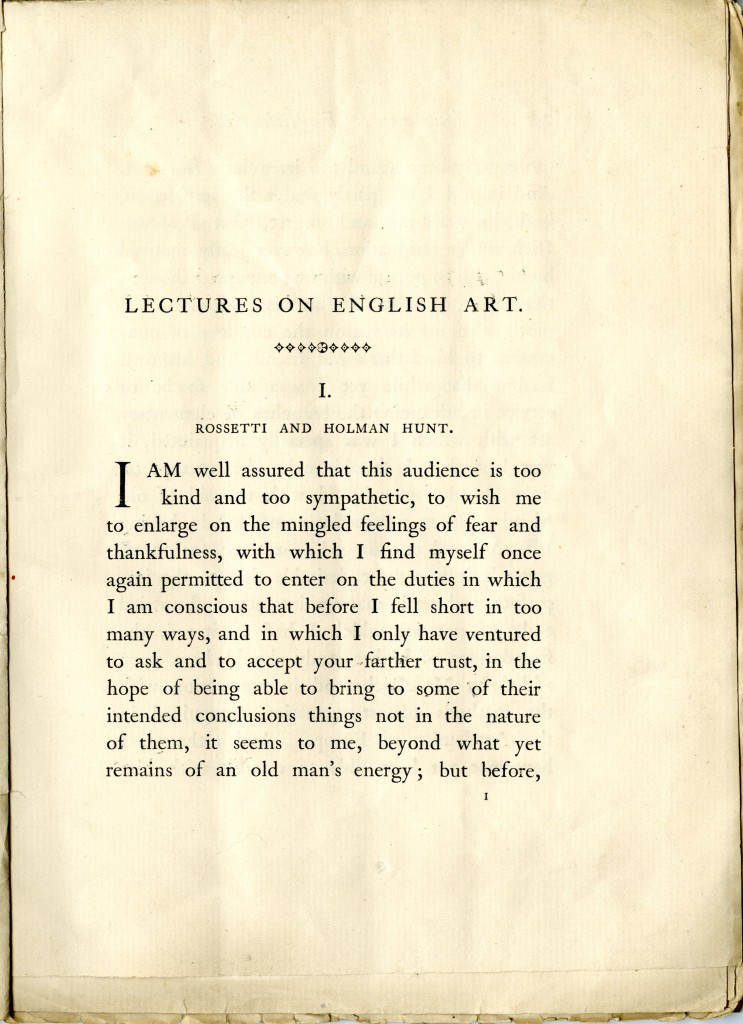

The ABL also owns the proof pages of Lectures on English Art : Rossetti and Holman Hunt, [The ODNB says they are Rossetti and Burne-Jones] which Ruskin has inscribed to “Lilias./ First proof./ With the Author’s love./ 27th March, 1883.”

John Ruskin. Inscription on cover page of proof pages of Lectures on English Art.

John Ruskin. proof pages of Lectures on English Art.

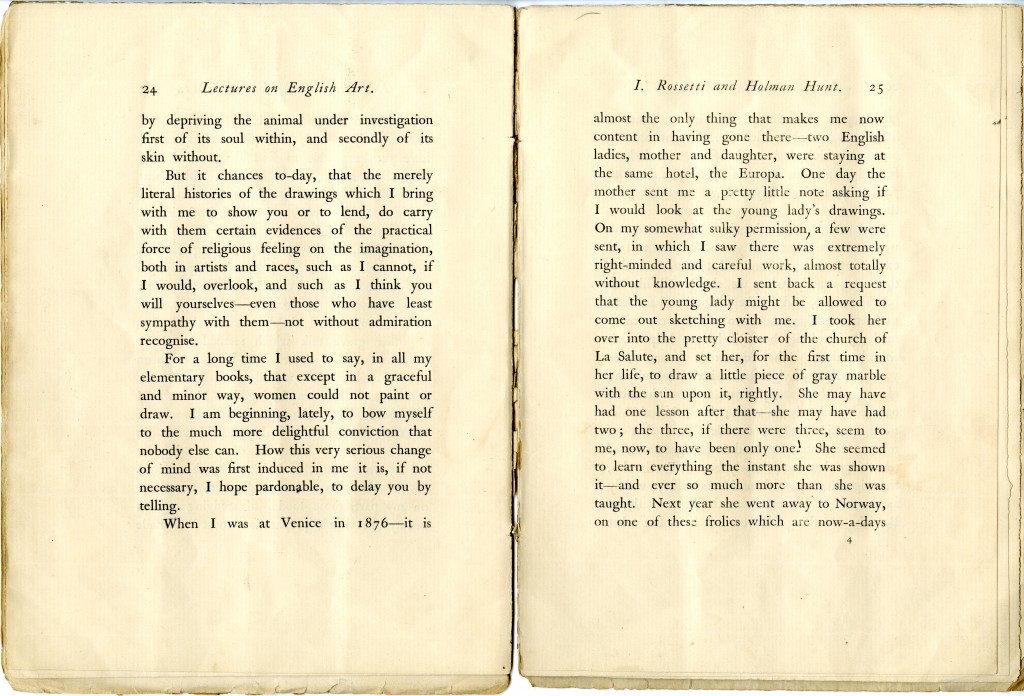

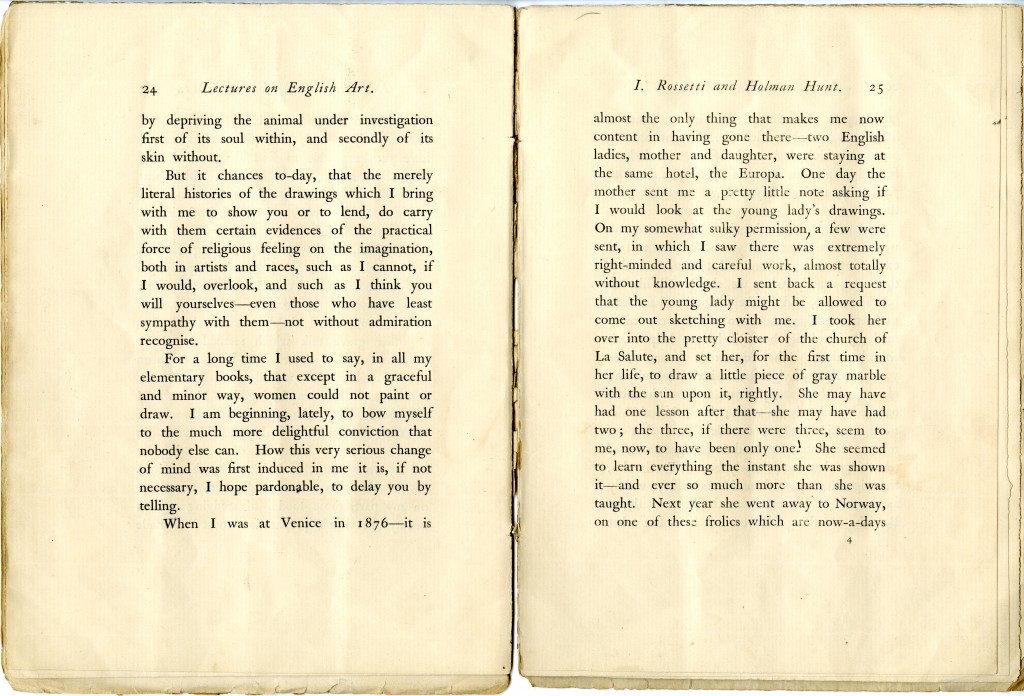

John Ruskin. Proof pages for Lectures on English Art. Pages 24 and 25.

In the lecture Ruskin describes his first meeting with Lilias:

When I was at Venice in 1876—it is almost the only thing that makes me now content in having gone there,—two English ladies, mother and daughter, were staying at the same hotel, the Europa. One day the mother sent me a pretty little note asking if I would look at the young lady’s drawings. On my some what sulky permission, a few were sent, in which I saw there was extremely right-minded and careful work, almost totally without knowledge. I sent back a request that the young lady might be allowed to come out sketching with me. I took her over into the pretty cloister of the church of La Salute, and set her, for the first time in her life, to draw a little piece of gay marble with the sun upon it, rightly. She may have had one lesson after that—she may have had two : the three, if there were three, seem to me, now to have been only one ! She seemed to learn everything the instant she was shown it—and ever so much more than she was taught.

The Ruskin Museum has made available to the Armstrong Browning Library several drawings and paintings by Lilias Trotter. Among the images is a drawing of a capital of a column. Perhaps this is the sketch to which Ruskin referred in his lecture.

Lilias Trotter. Column. Courtesy of Ruskin Library.

The Armstrong Browning Library also owns a page on which is mounted Ruskin’s handwritten notes from “Stones” in Modern Painters, Volume 6 (Chapter 18, Page 817). At the bottom of the page are sketches of Stonehenge, a stone frieze, and the Toad Rock.

John Ruskin. Drawings from Stones of Venice.

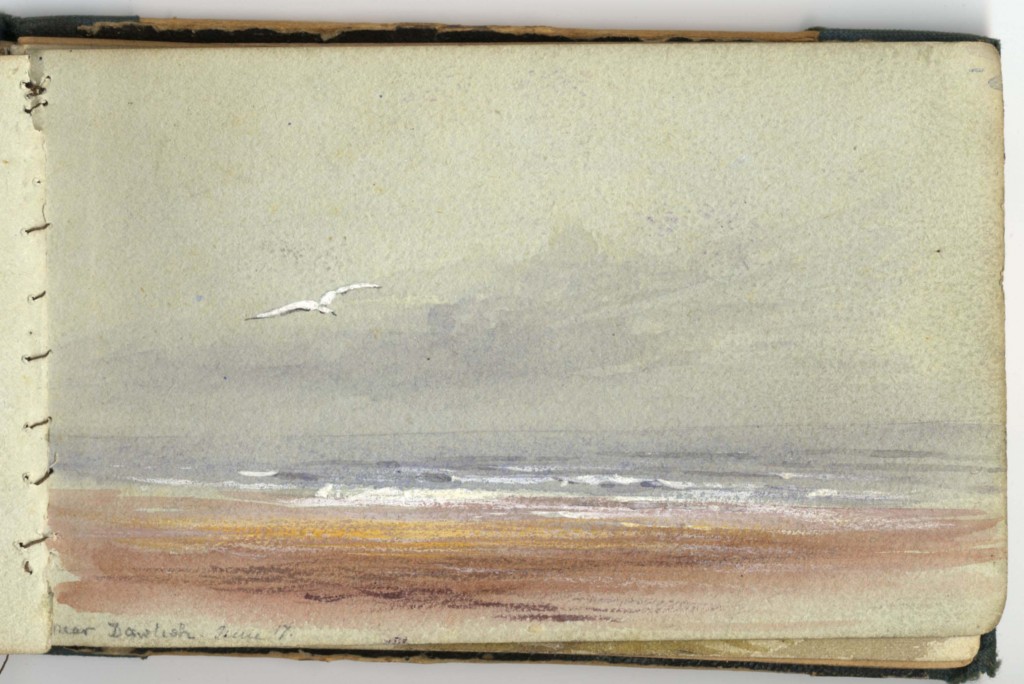

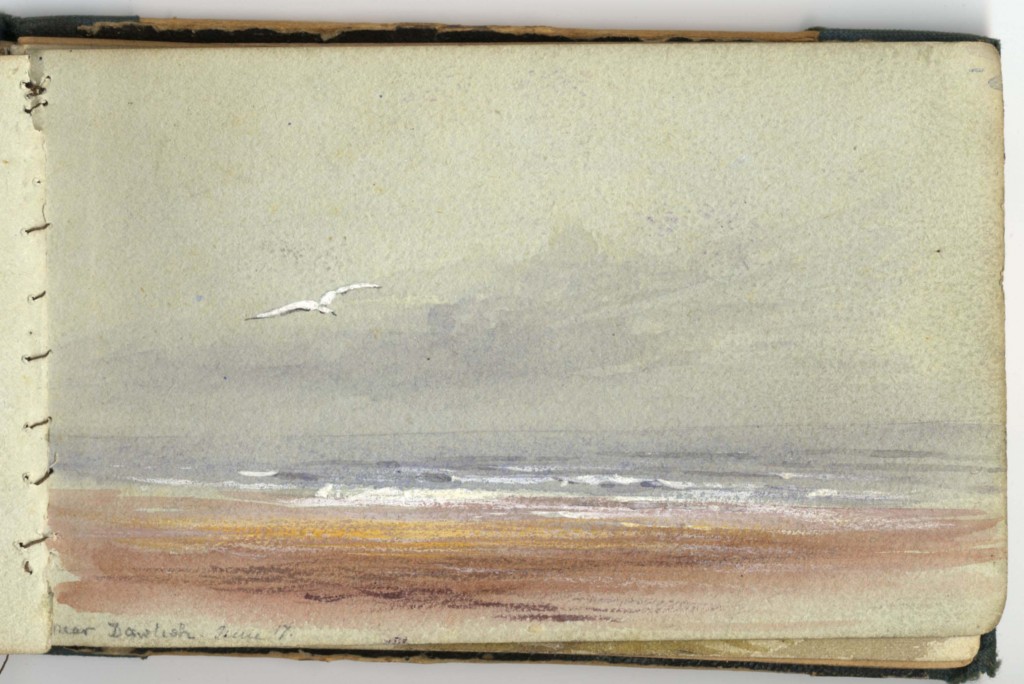

In the lecture, Ruskin tells of Lilias’s trip to Norway and her little sketchbook of drawings—“They can only be seen . . .with a magnifying glass, and they are patterns to you therefore only of pocket-book work ; but what skill is more precious to a traveller than that of minute, instantaneous, and unerring record of the things that are precisely best?”

Those drawings from the Norwegian sketchbook are now located at the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford. The sketches measures 2 in. X 4 in. A facsimile of Lilias Trotter’s 1876 Sketchbook: Scenes from Lucerne to Venice and Lilias Trotter’s 1889 Sketchbook: Scenes From North Africa, Italy & Switzerland are available for purchase. This illustration from her 1889 sketchbook of an ironwork cross illustrates the “pocket-book work” Ruskin described.

Lilias Trotter. “Cross” from Lilias Trotter’s Sketchbook of 1889. 2 in. X 4 in.

Following are the images of a few other drawings and paintings provided to the ABL from The Ruskin Library at Lancaster University:

Lilias Trotter. Figure Studies. Courtesy of Ruskin Library.

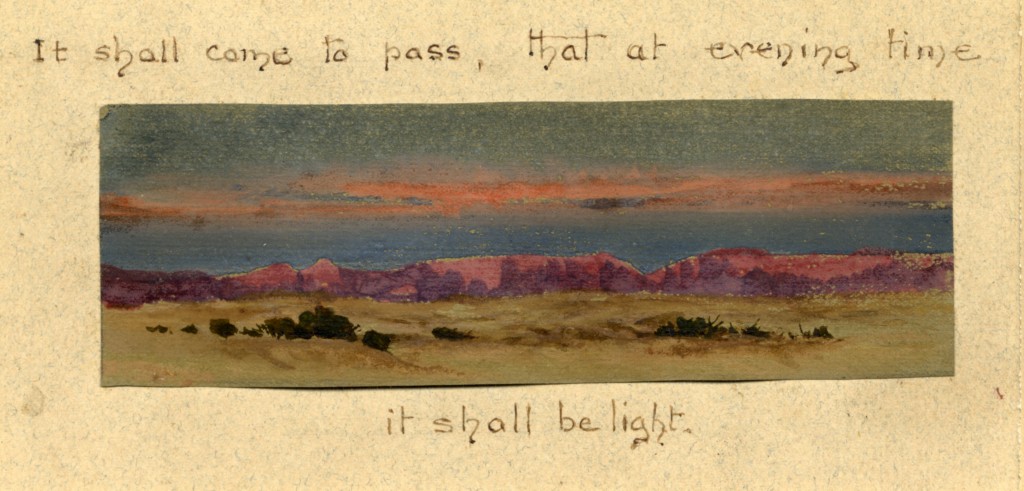

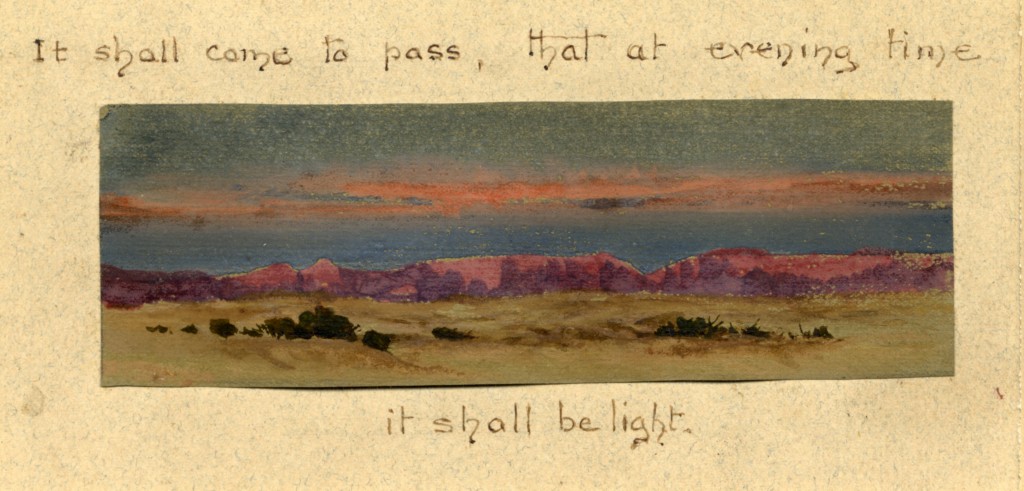

Lilias Trotter. Mountain Range and Desert. Courtesy of Ruskin Library.

Lilias Trotter. Image from Sketchbook-3. Courtesy of Ruskin Library.

Lilias Trotter. Image from Sketchbook-15. Courtesty of Ruskin Library.

Lilias Trotter. Daisies. Courtesy of Ruskin Library.

Lilias Trotter. Desert Flowers. Courtesy of Ruskin Library.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison001-1jwdp1q-652x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Pages 2 and 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison002-13paff6-1024x806.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison003-ro19ns-656x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Jane O'Meara] Simon. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Simon001-2kny3fk-686x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Jane O'Meara] Simon. 1 March 1863. Pages 2 and 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Simon002-21yybbs-1024x780.jpg)