By Melinda Creech, PhD, Graduate Assistant

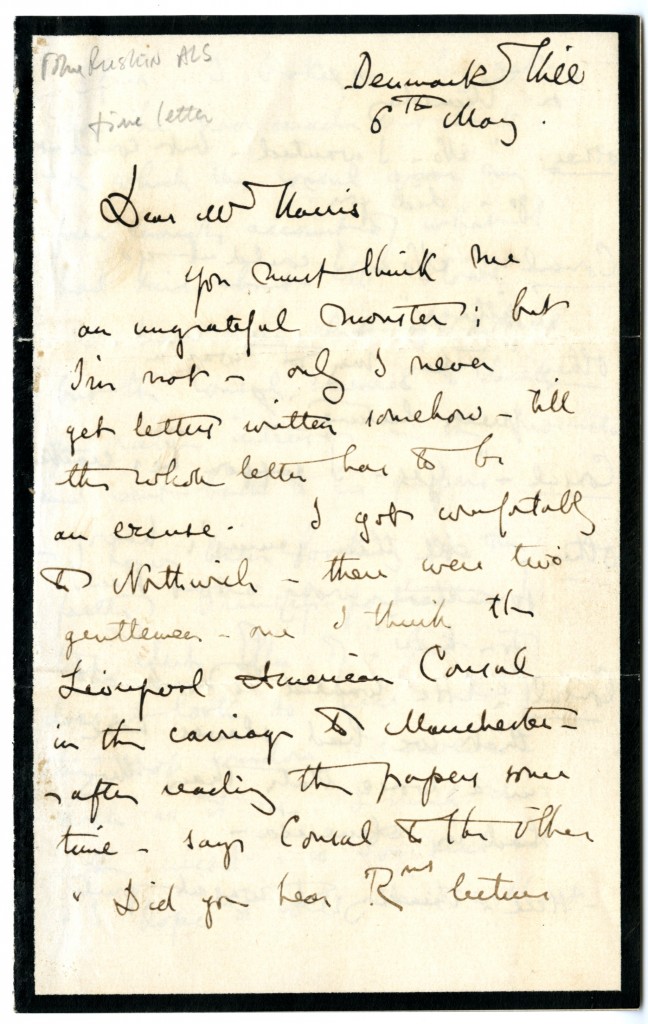

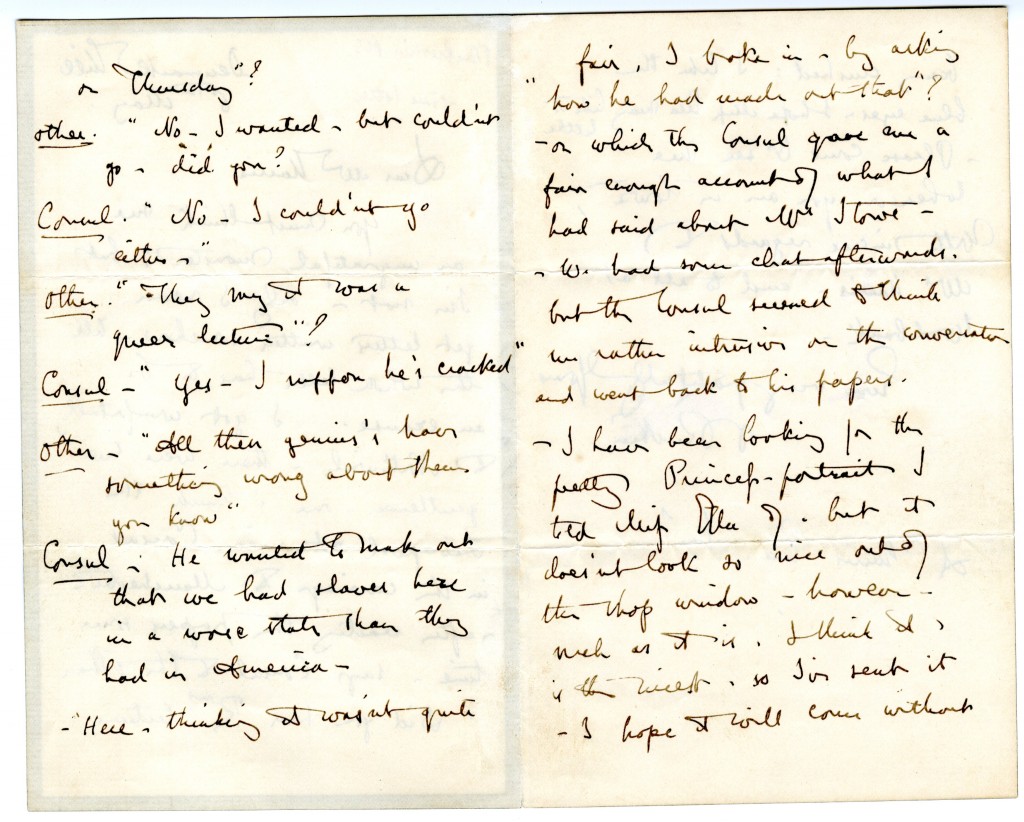

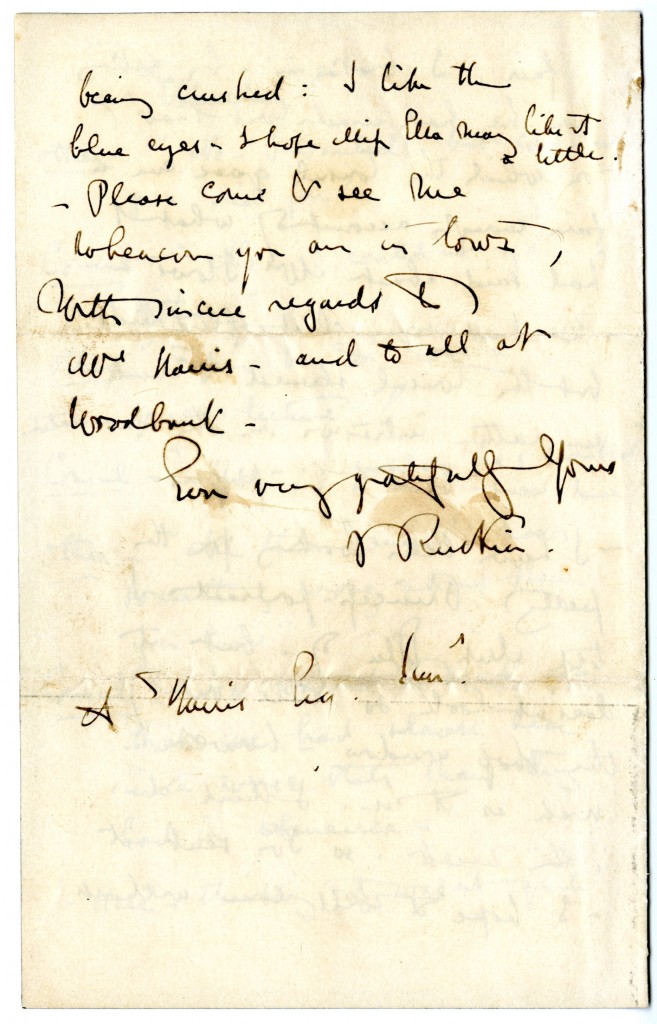

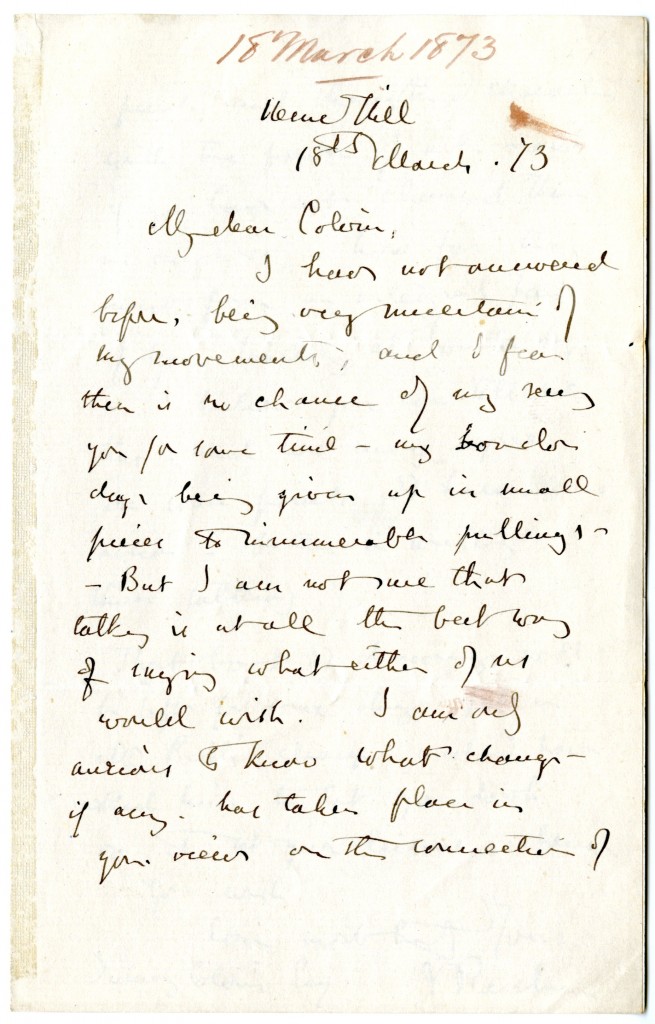

The Armstrong Browning Library is pleased to announce the release of The Victorian Collection online. This new digital collection contains over 3,000 letters and manuscripts connected to prominent and lesser known British and American figures and complements the Armstrong Browning Library’s unparalleled collection of materials relating to the Victorian poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The letters and manuscripts in this growing collection can be browsed and searched by date, author, keyword, or first line of text. Letters from the collection are currently on display in Hankamer Treasure Room.

The Armstrong Browning Library is pleased to announce the release of The Victorian Collection online. This new digital collection contains over 3,000 letters and manuscripts connected to prominent and lesser known British and American figures and complements the Armstrong Browning Library’s unparalleled collection of materials relating to the Victorian poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The letters and manuscripts in this growing collection can be browsed and searched by date, author, keyword, or first line of text. Letters from the collection are currently on display in Hankamer Treasure Room.

~~~~~

Theater, Art, and Music

In addition to letters from literary figures, letters about science, exploration, religion, and politics, many letters related to the arts — theater, visual arts, and music — are also a part of the Victorian Collection.

The ABL owns an album once belonging to Fanny Kemble, (1809-1893), a notable British Actress. The album contains letters to Mrs. Kemble from such notables as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Charlotte Cushman, Owen Wister, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and James Ballantyne. Mrs. Kemble’s note below comments on Mr. Ballantyne’s review of her work and points to a favorable opinion by Sir Walter Scott.

*****

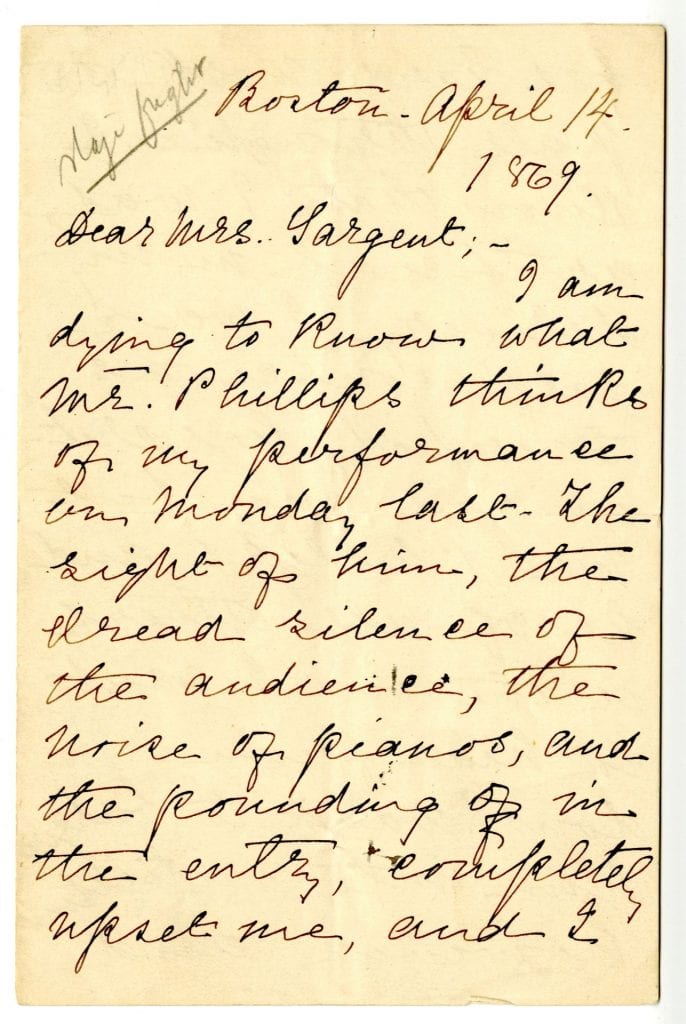

The ABL also owns twenty-two letters from Kate Field, an American journalist, correspondent, editor, lecturer, and actress. Her letters are always rather flamboyant, often written in purple ink. In this letter she is very nervous about Mr. Phillips opinion of her performance. She writes to Mrs. Sargent—

I am dying to know what Mr. Phillips thinks of my performance on Monday last. The sight of him, the dread silence of the audience, the noise of pianos, and the pounding in the entry, completely upset me, and I had hard work to pull through – I know that I was artificial in my delivery I was self-conscious. Everybody has criticized me but Mr. Phillips, and he of all others is the one I want to hear from. I don’t want to badger him into criticism, however, and I ask you to be my messenger.

Kate Field performed “Woman at the Lyceum” on Monday, 12 April 1869 in New York.

*****

Percy Florence Shelley, the only surviving son of Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and novelist Mary Shelley, inherited the baronetcy from his grandfather and spent most of his life involved in the theater, building a theater in his home, Boscombe Manor. Many of his friends acted in and attended the productions, including Henry Irving and Robert Louis Stevenson. This letter to Tom Taylor, English dramatist, critic, biographer, public servant, and editor of Punch magazine, relates some details of the Shelley’s family life and describes the plays that were being planned for the theater.

*****

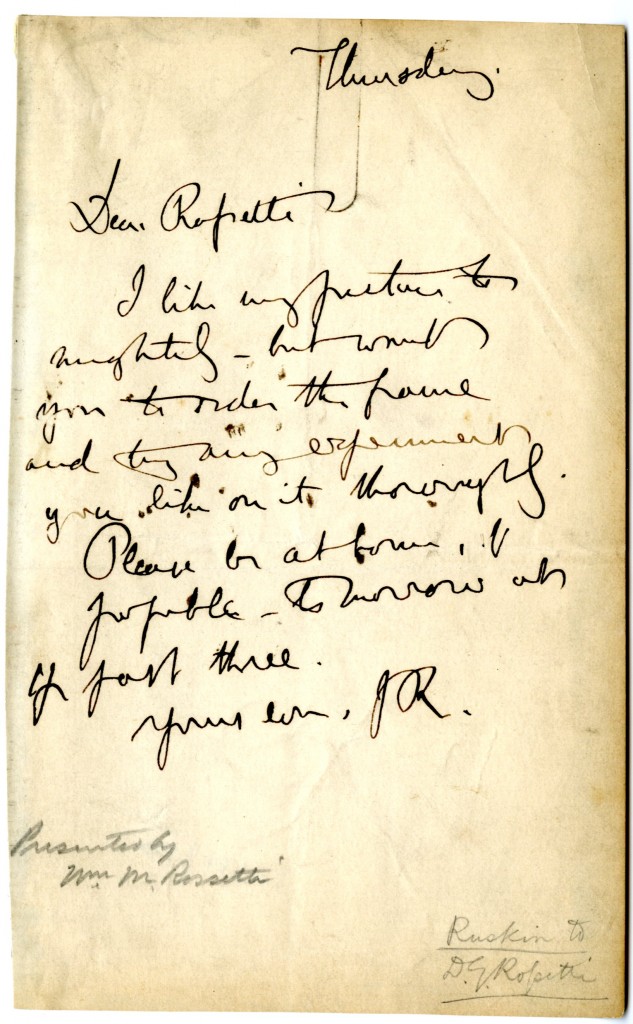

The ABL also has a collection of letters written to Tom Taylor. Most of the letters are letters of condolence to his wife upon his death. One of the letters is from Richard Doyle, a noted illustrator during the Victorian era, particularly in Punch magazine. The letter informs Taylor that Doyle has found the misplaced sketch of a view from Tennyson’s window. In March 1856, during a visit that Doyle and Tom Taylor had made to Farringford House, Doyle had done a drawing of the view from Tennyson’s window (“View from the Drawing Room painted in 1856 by Richard Doyle”). The letter contains a wonderful drawing of Tennyson and his family.

*****

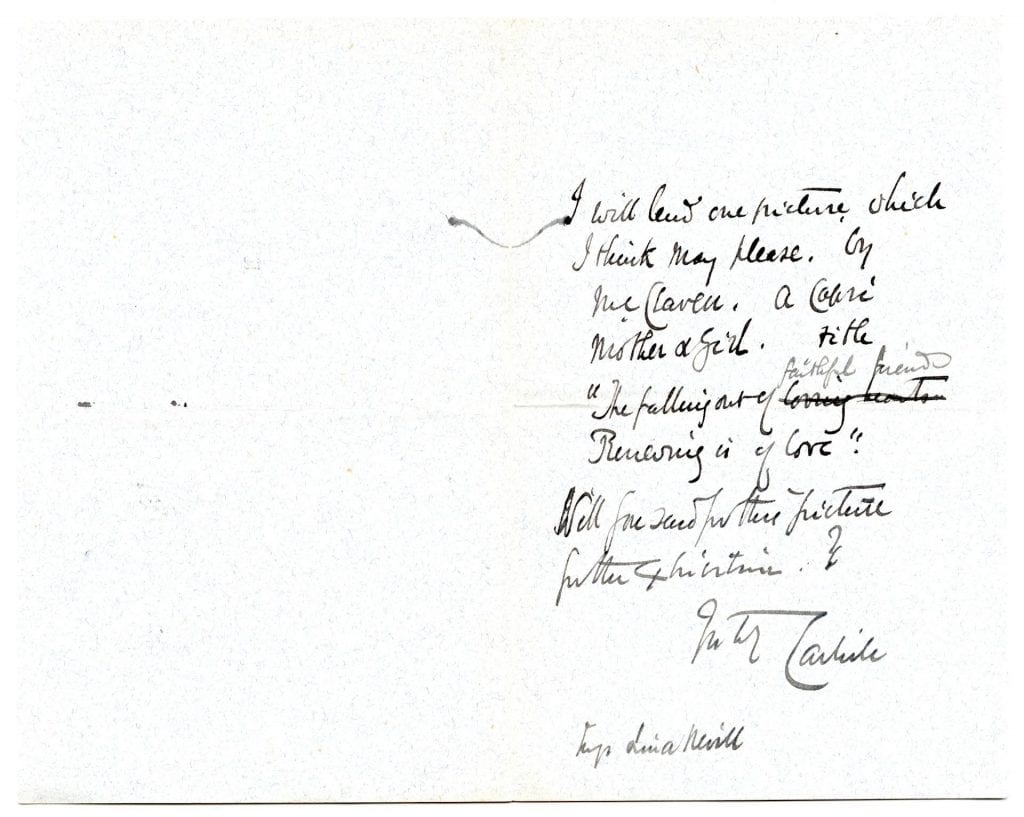

The Nevill Album contains letters pertaining to the visual and performing arts. Lina Nevill, novelist and Secretary of the Women’s University Extension, arranged for several public exhibitions of art, including the Southwark Exhibition in 1891. The Earl of Carlisle sent a painting by Walter McClaren, “A Capri Mother and Girl” for the Exhibition.

*****

The Norris Album contains several letters focused on music. This letter, from Hungarian violinist Ludwig Straus, is written in musical annotation and German.

*****

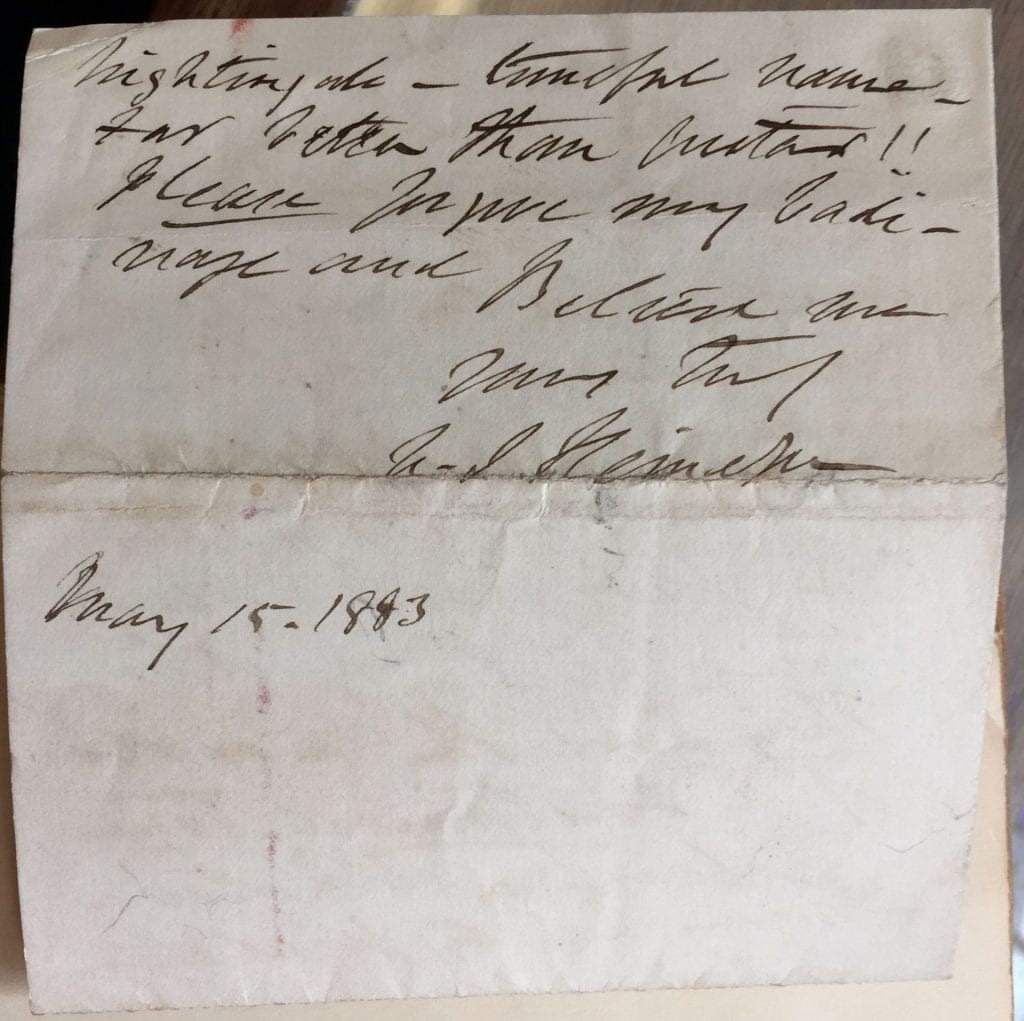

In this letter N. J. Heineken, a musician and contributor to the journal, The Musical Standard, bemoans the fact that Miss Hodge has asked him a question about the guitar. He says:

It will never repay you for the learning its twinkle, twinkle, tunes may serve the purpose of the love sick swain as a serenading instrument but is most beneath the attention of he who can appreciate the old Cantors [glorious] [fuges]…

In another letter to Miss Hodge, Heineken praises and critiques Miss Hodge’s composition, affirming that “I have been much pleased with your truthful and ingenious song.”

~~~~~

For the complete series of blog posts on the Victorian Collection:

- Introducing … The Victorian Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library: A Baylor Libraries Digital Collection

- Introducing … The Victorian Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library: A Baylor Libraries Digital Collection – Science & Exploration

- Introducing … The Victorian Collection at the Armstrong Browning Library: A Baylor Libraries Digital Collection – Religion & Politics

Literary figures represented in the Victorian Collection are covered in the blog series: Beyond the Brownings

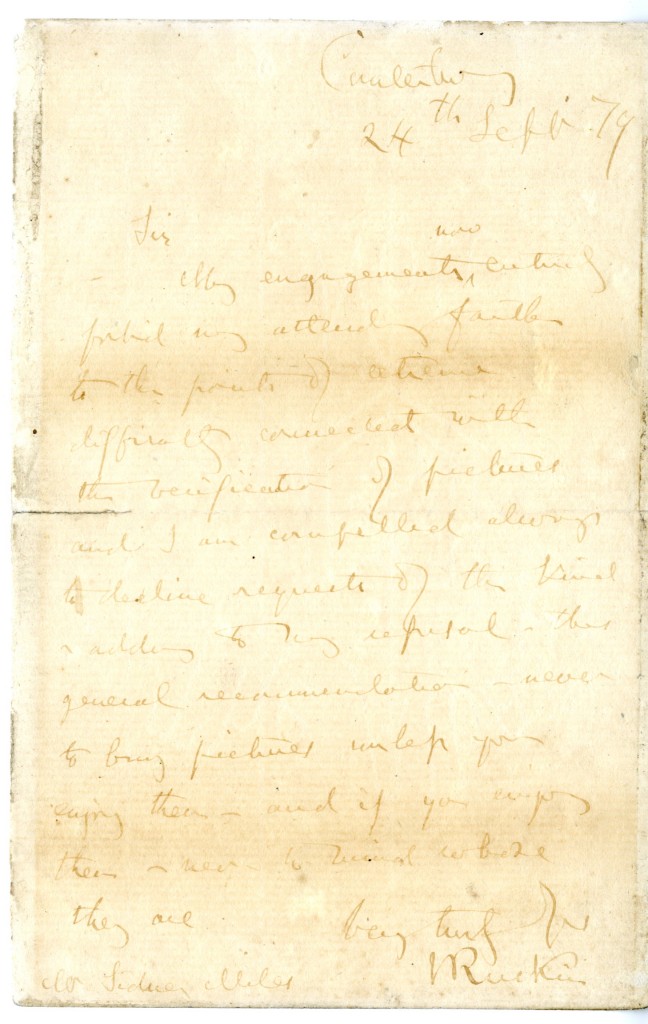

![Letter from John Ruskin to [William] Kingsley. 18 February 1886. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-William-Kingsley015-1nh5387-658x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to Tom Taylor. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Taylor014-1bq7kpb-673x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Unknown]. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Unk-14a52wp-807x1024.jpg)