Borrowing its title from a collection of essays by C. S. Lewis, this series, “They Asked For A Paper,” highlights interesting items from the Armstrong Browning Library’s collection and suggests topics for further research.

By Melinda Creech

Manuscripts Specialist, Armstrong Browning Library

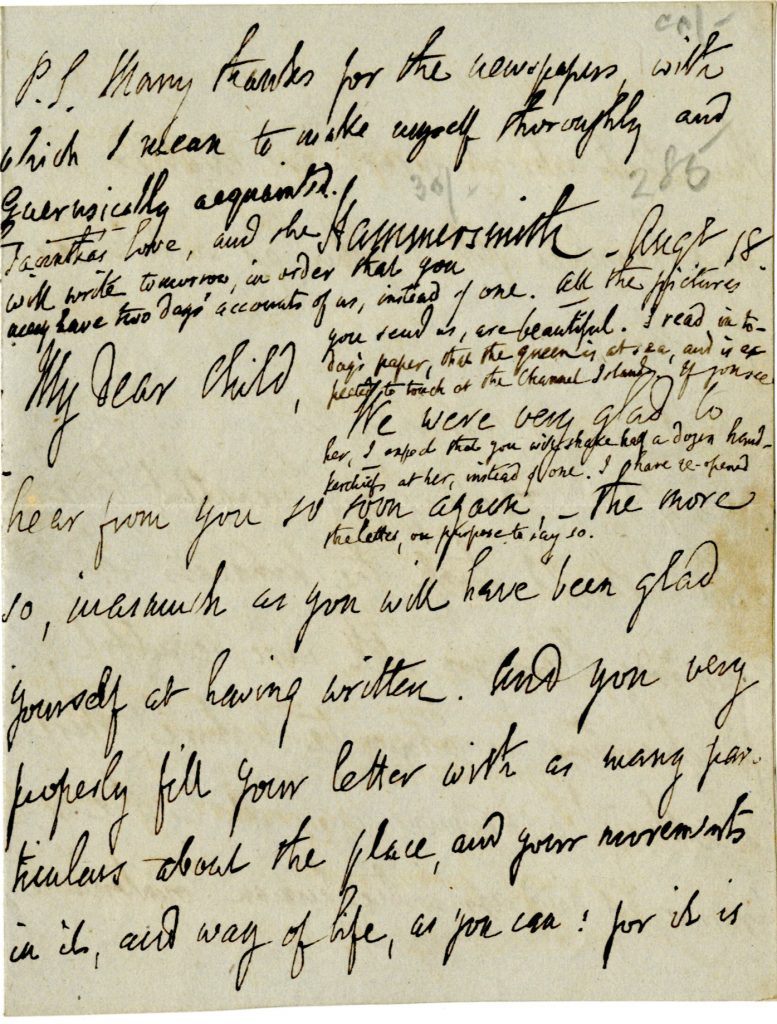

Among the items in the Armstrong Browning Library’s collection is a tender letter from Leigh Hunt to his daughter, Julia Trelawney. She is staying on the Isle of Guernsey with George Godfrey. Although the letter is published in The Correspondence of Leigh Hunt (Smith, Elder and Company, 1862, page 281) parts of the letter were elided, including the delightful line at the beginning of the postscript:

Many thanks for the newspapers with which I mean to make myself thoroughly and Guernsically acquainted.

A transcript of the letter is provided below; the unpublished parts are in bold.

Hammersmith — Augt. 18

My dear Child,

We were very glad to hear from you so soon again, — the more so, inasmuch as you will have been glad yourself at having written. And you very properly fill your letter with as many particulars about the place, and your movements in it, and way of life, as you can; for it is

[Page 2]

this that absent friends are enabled to find themselves still together, as much as is possible.

I should certainly exclaim as you say I should, in threading your “beautiful” lanes; and I should think the kindness which every body shews you still more beautiful; for charming as inanimate nature ^is,^ there is nothing so charming, after all, as the expression of kindness in the human countenance.

[Page 3]

Pray look at the “house to let” by all means, and at any other house to let, provided itdoes^would^ not tax ^my^ old limbs to get up to it. And be particular as to their rents and their gardens. I rejoice in what you tell me of your sitting at the piano. Walter has not yet come; but we saw Mr. & Mrs. Hooper here again on Thursday evening. Mr. Ollier and Edmund spent the greater part of Saturday evening with us; and simultaneous with their appearance was that of Mary Sayer, whom Jacintha

[Page 4]

entertained at tea in the back parlour while we took ours in the front, but all with open doors and in good fellowship; only Mr. Ollier’s health, I am sorry to say, continuing to be much tried, and strangers trying it more, we remained as I describe. She is coming to tea again on Wednesday evening to play us some Beethoven, and repeat some verses of mine in a kind of recitative, occasionally touching the instruments. We are still looking anxiously for Mr. Lee; and the moment he comes I will let you know. I tell you of Wednesday evening in order that you may imagine yourself with us: [so] [now] you know ^as much of^ us, past and future, as we know ourselves.

Your ever loving father

L. H.

[Written on top of Page]

P. S. Many thanks for the newspapers with which I mean to make myself thoroughly and Guernsically acquainted. Jacintha’a love, and she will write tomorrow, in order that you may have two days’ accounts of us, instead of one. All the pictures you send us, are beautiful. I read in today’s paper, that the queen is at sea and is expected to touch at the Channel Islands. If you see her, I expect that you will shake half a dozen handkerchiefs at her, instead of one. I have re-opened the letter, on purpose to say so.[Envelope]

Postmark:

LONDON

AU 18

57

Miss Hunt —

Care of Geo: Godfrey Esqre

Claremont House,

Rohais,

Guernsey.

Channel Islands

L. H.

The tiny letter (3.5″ x 4.5″) is tucked into an envelope mounted on the same page as a letter from Sir Walter Scott to Right Honorable The Lord Chief Baron &c &c Edward.

The letters are collected into an album which belonged to “Henry De Castro / Cramlington Villa — Putney.”

Why is Leigh Hunt’s daughter on Guernsey? Who are the people she is staying with? Who are the other people mentioned in the letter? How did this letter get into Henry DeCastro’s collection? What are the “houses to let” he mentions? Why is the letter written on mourning paper? Is there a copy of the newspaper with which Hunt “Guernsically acquainted” himself?

Why is Leigh Hunt’s daughter on Guernsey? Who are the people she is staying with? Who are the other people mentioned in the letter? How did this letter get into Henry DeCastro’s collection? What are the “houses to let” he mentions? Why is the letter written on mourning paper? Is there a copy of the newspaper with which Hunt “Guernsically acquainted” himself?

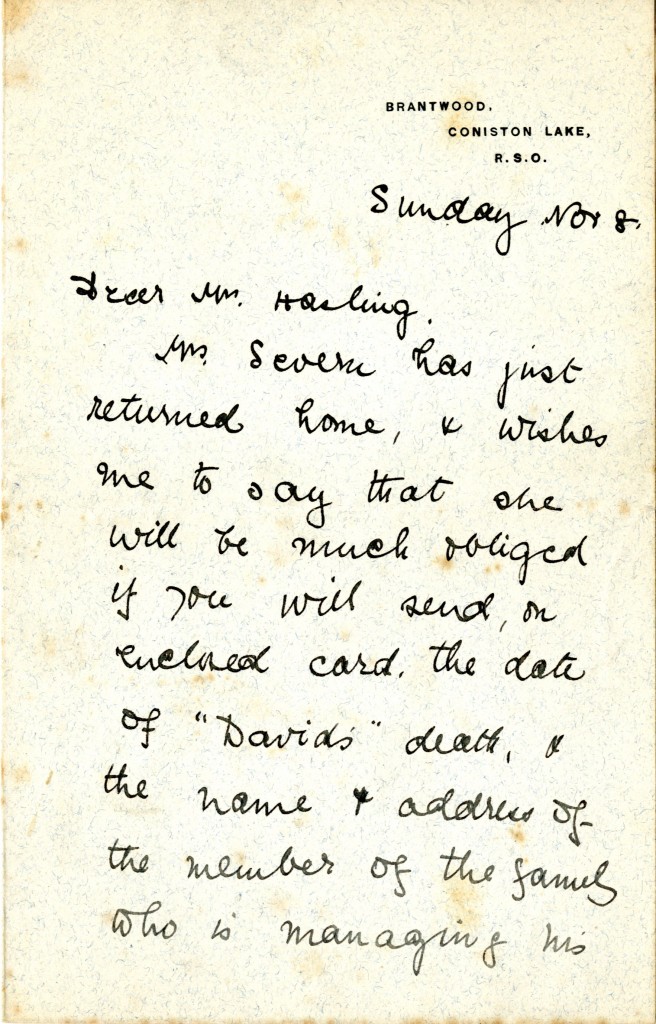

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-1-zu023x-1024x680.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 2.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-2-1j5hcqf-1024x674.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-3-1bp156v-1024x675.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-4-2f4omtz-1024x674.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-1885-1887-1-1kvnc63-1024x668.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 2.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.1885-1887-2-1kifm1n-1024x678.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.1885-1887-3-21hv1d0-1024x671.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-1885-1887-4-1hkh6d7-1024x652.jpg)

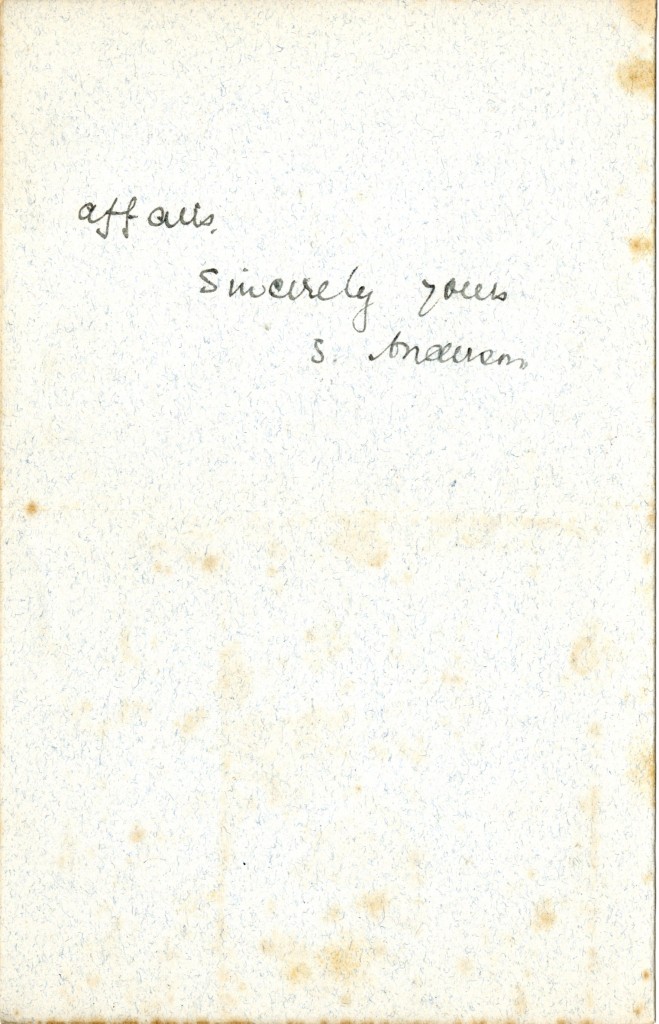

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison001-1jwdp1q-652x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Pages 2 and 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison002-13paff6-1024x806.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to W. H. Harrison. 10 November [1851]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Harrison003-ro19ns-656x1024.jpg)

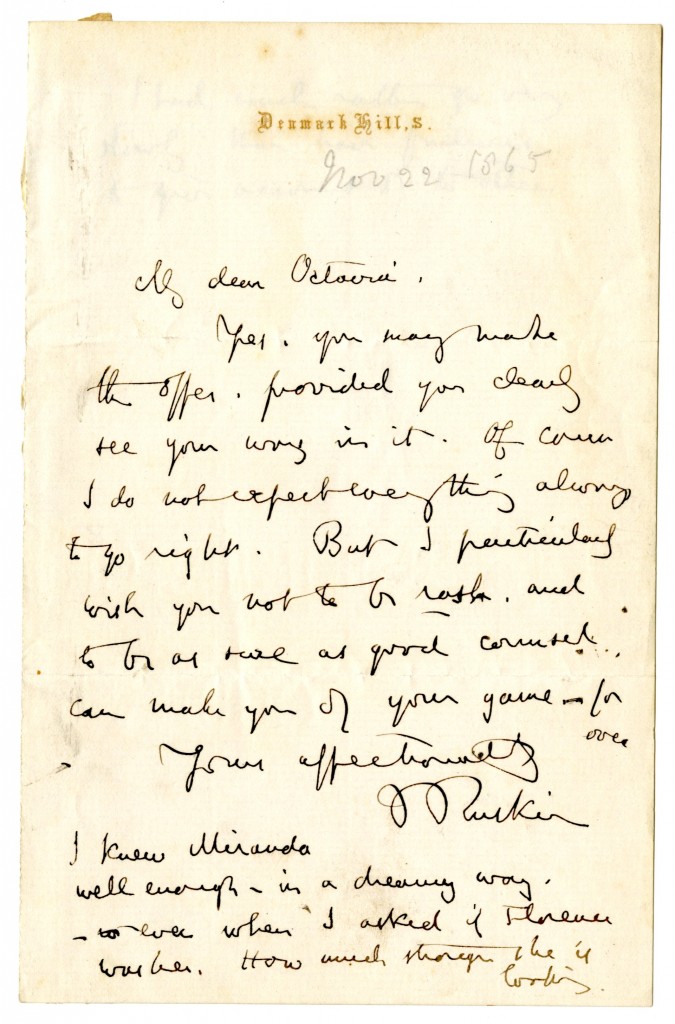

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Jane O'Meara] Simon. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Simon001-2kny3fk-686x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Jane O'Meara] Simon. 1 March 1863. Pages 2 and 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Ruskin-to-Simon002-21yybbs-1024x780.jpg)

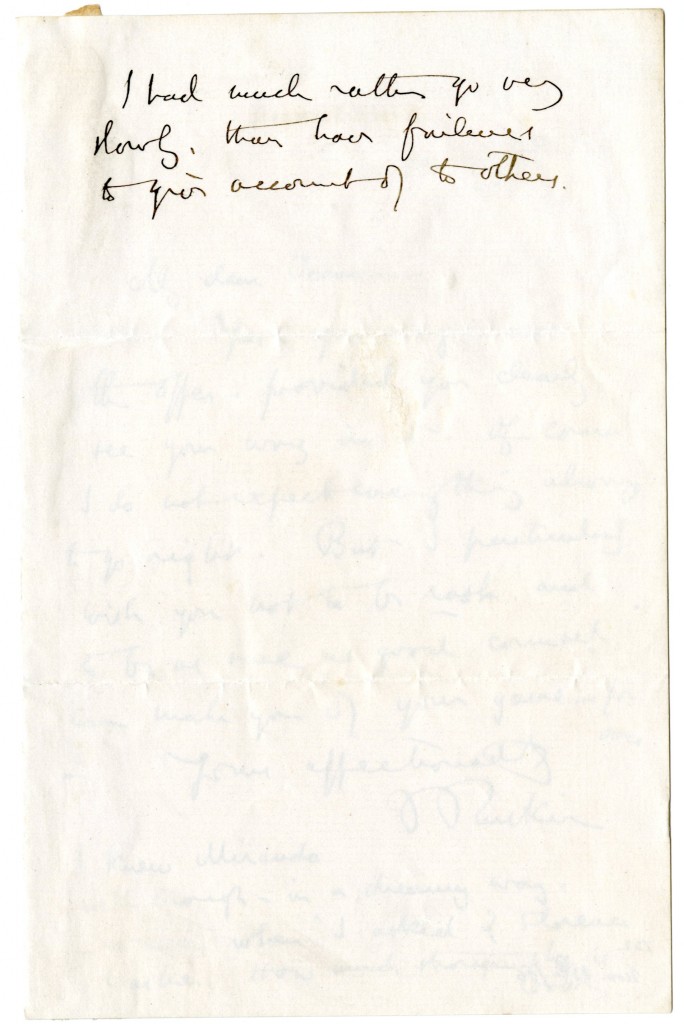

![John Ruskin to John Pakenham Stilwell. 14 February [ny].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Stilwell-14-February-ny-1013-y5v810-651x1024.jpg)

![John Ruskin to John Pakenham Stilwell. 14 February [ny].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Stilwell-14-Februaty-ny-2014-2gmvfqu-644x1024.jpg)

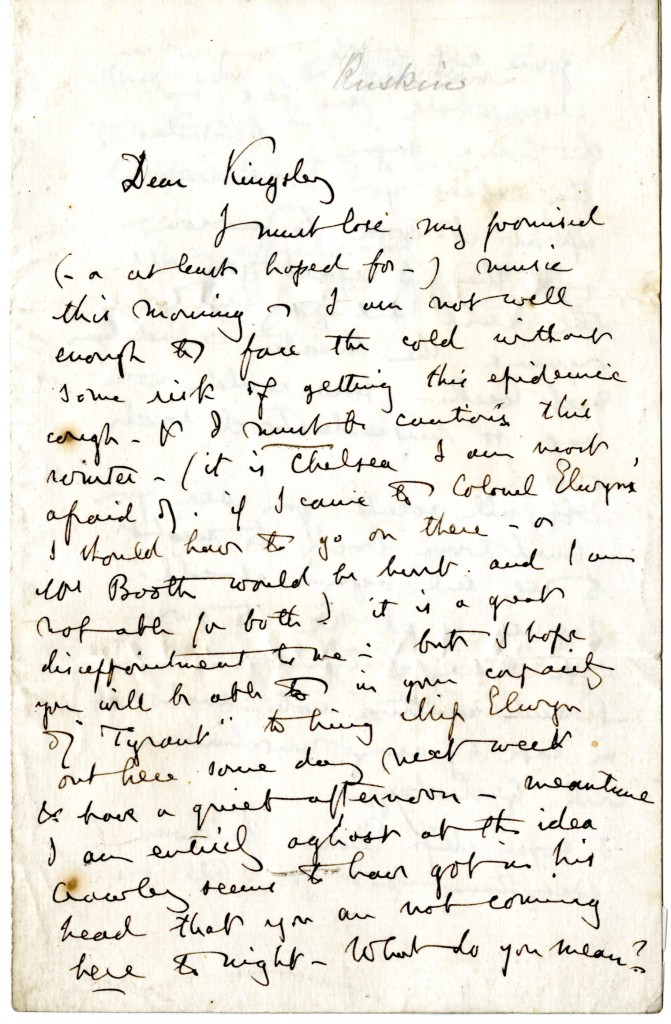

![Letter from John Ruskin to [William] Kingsley. 18 February 1886. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-William-Kingsley015-1nh5387-658x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to Tom Taylor. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Taylor014-1bq7kpb-673x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Unknown]. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Unk-14a52wp-807x1024.jpg)