‘Every common bush afire with God’: Divine Encounters in the Living World

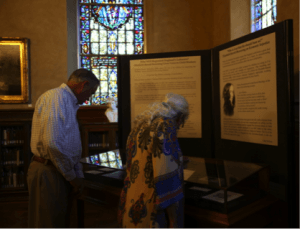

The exhibition explores the intersection of religious and ecological concerns in nineteenth-century literature and art, from William Wordsworth to Gerard Manley Hopkins. The exhibit was curated by Molly Lewis, a doctoral student of English at Baylor University during a ten-week summer internship through the Armstrong Browning Library.

Recognition, Prayer & Gratitude in the ABL’s Archives

This fall, the Armstrong Browning Library is hosting “‘Every common bush afire with God’: Recognition, Prayer & Gratitude in the Nineteenth Century,” an exhibition on the intersection of ecology and religion in the work of some of the century’s most admired poets and artists. Many nineteenth-century British writers were deeply concerned with the destructive consequences of the Industrial Revolution on their natural environment, both as artists of the written word and as deeply religious thinkers. Much of their concern with the despoliation of the natural world stems from their conviction that we encounter God through the living world of plants, animals, water, sky. These writers believed that humanity is not alone in bearing the image of God; all of creation reflects the divine. Recognizing this divine reflection in nature makes prayerful communion with God possible. But, by extension, harming the earth can further separate us from God. The writers and artists represented here were inspired in their own creative acts—works of art like poetry and painting—as they paid attention to and cared for the world of nature around them. Through their words and images, we may better understand how a robust faith encourages us towards better care for creation in the twenty-first century.

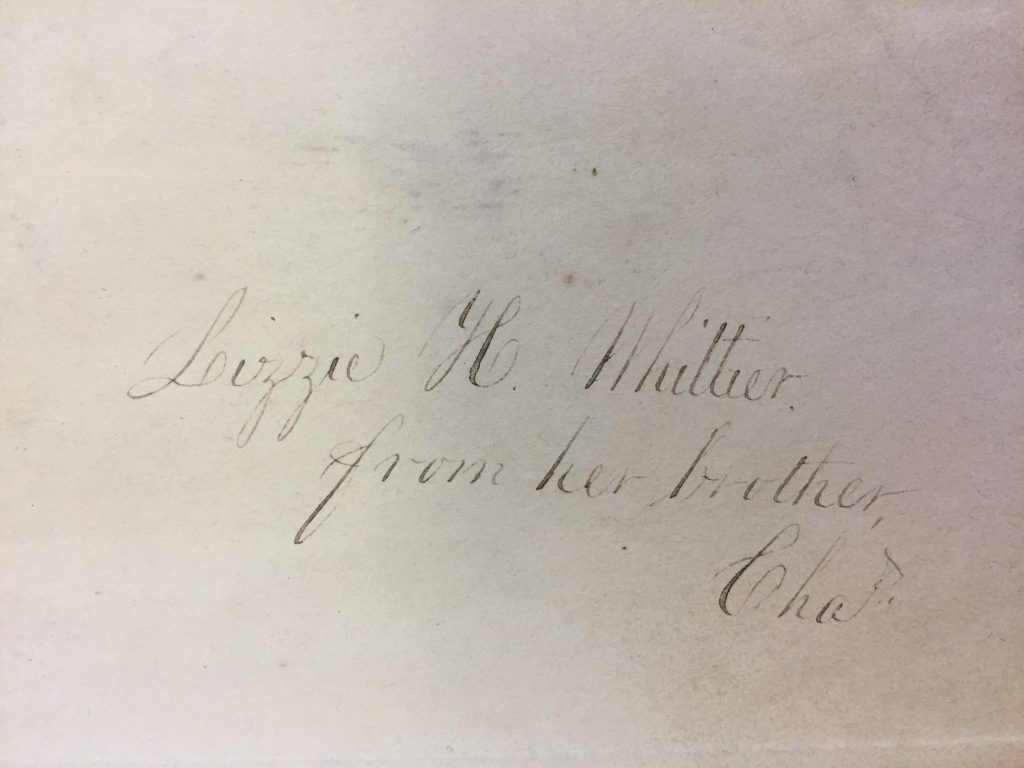

William Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey,” from Wordsworth’s Poetical Works. Volume 2. London: Edward Moxon, 1836. The Brownings’ Library. P. 162.

The exhibition is broken up into three parts, focusing in turn on “Recognition,” “Prayer,” and “Gratitude” as they relate to human participation in the natural world. Throughout the nineteenth century, writers like Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861), Christina Rossetti (1830-1894), Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889), and others, saw that both humanity and the natural world are cared for by God. These poets warn against simply using nature rather than recognizing its value in God’s eyes, and suggest that attending to nature’s inherent dignity may lead to a better understanding ourselves of what it means to be children of a creative God. These poets encourage us to ask: What have we missed out on because of the carelessness of our nineteenth-century ancestors? What will our own children miss out on because of our carelessness today?

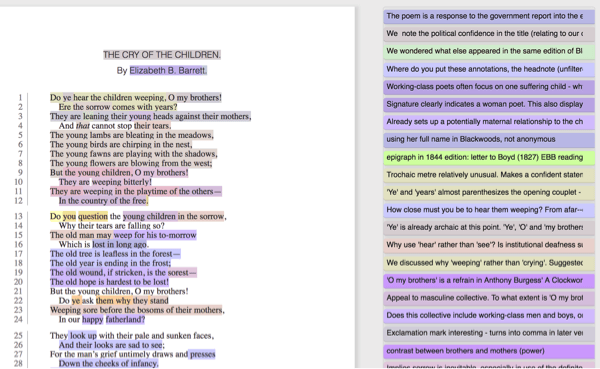

The section on “Recognition,” highlights Barrett Browning’s “Patience Taught by Nature,” Hopkins’s poem, “Binsey Poplars,” and Christina Rossetti’s “Innocent Eyes Not Ours.” When Elizabeth Barrett Browning writes, “Grant me some smaller grace than comes to these,” she implies that non-human nature receives God’s grace as freely as humanity does. In “Binsey Poplars,” Gerard Manley Hopkins argues that deliberately harming nature is actually an act of violence against God. Rossetti’s poem is an excerpt revised from her longer work, “To What Purpose Is This Waste?” published by her brother William Michael Rossetti after her death. Both the excerpt and the full poem challenge readers to consider the nature’s value apart from its utility in human industry. Rossetti suggests that such value lies in nature’s inherent posture of praise: “All voices of things inanimate / Join with the song of Angels and the song / Of blessed spirits, chiming with / Their Hallelujahs.” If the natural state of the created world is continual praise of God, we are challenged to treat the natural world with the same reverence we give to the rest of his children. Moreover, we can even learn from nature how best to do praise the Creator ourselves.

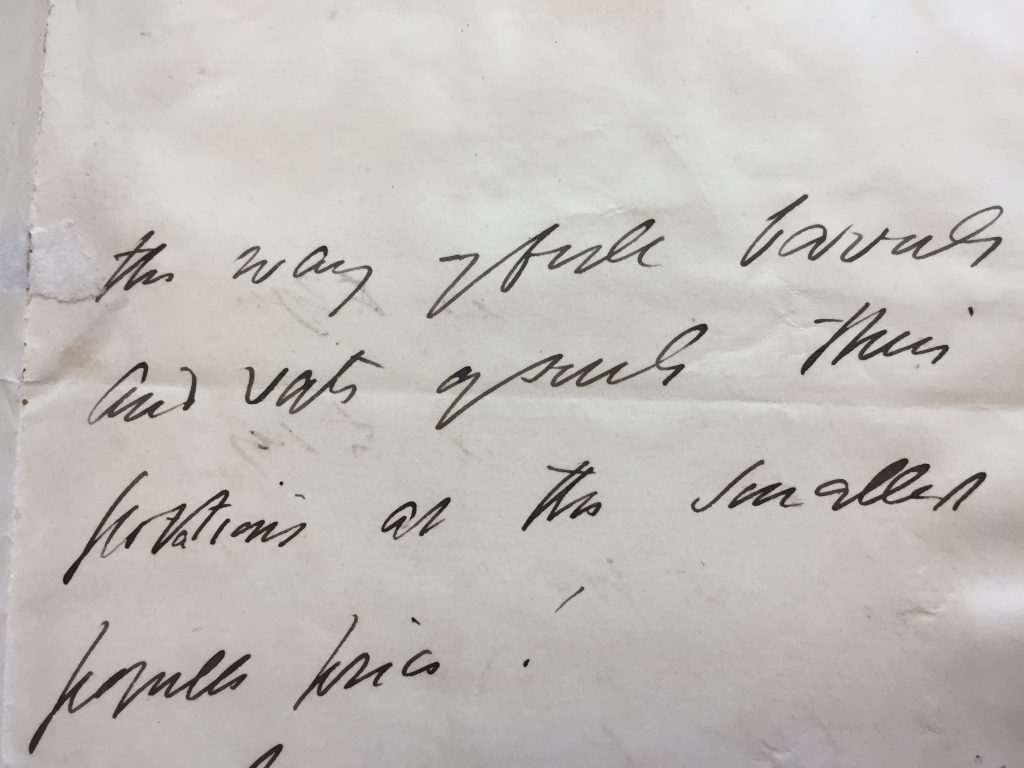

The exhibition’s second section on “Prayer” compares works by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, William Wordsworth (1770-1850), Christina Rossetti, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) to see how the theme of prayer through nature is carried across the century. In his poem “Tintern Abbey,” William Wordsworth suggests that the mere memory of nature can restore him when he is confined to “lonely rooms, and ‘mid the din / Of towns and cities.” Wordsworth’s dear friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge and later poets like Elizabeth Barrett Browning draw on such encounters with nature to suggest that being attentive to the created world makes us better able to pray. Whether through the limited view of a window or tramping about on the holy ground of the earth, honoring nature brings us closer to God.

Barrett Browning’s poetic novel Aurora Leigh offers two especially helpful scenes in which the title character discovers this truth for herself. Confined, like Barrett Browning herself, to a bedroom with a single window connecting her to the natural world, Aurora is struck by the reminder (brought to her by the light of the sun) that God has heard nothing from her but tears in many days. Gradually, as she sits by the window and strokes the leaves of the woodbine just outside, her spirits awakes to life and love. “Wholly, at last,” she cries, “I wakened, opened wide my window and my soul.” Much later on a journey through Italy, Aurora continues her reflection on nature’s capacity to draw the viewer to God. “Earth’s crammed with heaven,” she writes, “And every common bush afire with God.” For Barrett Browning, the natural world is more than material. Like the human person, it bears the stamp of the divine presence. Recognizing its beauty can thus draw us closer to the Creator—even as harming nature drives us away from him.

The exhibition’s third section on “Gratitude” shows how artists and writers like William Morris (1834-1896), John Ruskin (1819-1900), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), and Robert Browning (1812-1889) respond to nature in their art and writing, reflecting the beauty of the ordinary world with gratitude and care. Art and social critic John Ruskin argues in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) that “God is a household God, as well as a heavenly one,” encouraging readers to not abandon the world around them for an eternal utopia. He writes:

“God has lent us the earth for our life; it is a great entail. It belongs as much to those who are to come after us…as to us; and we have no right, by anything that we do or neglect, to…deprive them of benefits which it was in our power to bequeath.”

Ruskin’s language of attending to future generations resonates with current conversations about environmental care. In his own time, poets and painters alike were moved by his challenge to create in harmony with the natural world rather than in antagonism with it. In turn, their work inspires readers like us to respond with our own acts of creation—and creation care.

Read more in this series of blog posts about the exhibit “‘Every common bush afire with God’: Divine Encounters in the Living World“:

- ‘Every common bush afire with God’: Recognition, Prayer & Gratitude in the ABL’s Archives

- “Every common bush afire with God”: How Shall We Live Now?

- ‘Every common bush afire with God’: Welcome to the Process

- ‘Every common bush afire with God’: Things Not Shown