‘Every common bush afire with God’: Divine Encounters in the Living World

The exhibition explores the intersection of religious and ecological concerns in nineteenth-century literature and art, from William Wordsworth to Gerard Manley Hopkins. You can read more about its content here. The exhibit was curated by Molly Lewis, a doctoral student of English at Baylor University during a ten-week summer internship through the Armstrong Browning Library.

Things Not Shown: What Didn’t Make It into the Exhibit

The Armstrong Browning Library holds a first edition of Matthew Arnold’s New Poems, including what is perhaps his most famous, “Dover Beach.” Hardly an argument for religion’s advocacy for ecological care, “Dover Beach,” provides a sobering counterpoint to many of the texts displayed in this fall’s exhibition, “‘Every common bush afire with God: Divine Encounters with the Living World.” While most of the exhibition’s writers and artists advocate for creation care because of nature’s participation in the grace and presence of God, Arnold’s poem argues the reverse. Rather than being “afire with God,” the natural world is empty of divine purpose or presence:

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world. (113)

Arnold’s image of the “Sea of Faith…Retreating” represents for many what religious faith in the nineteenth century looked like. In the face of scientific and industrial progress, little room was left for the mystery of a divine Creator.

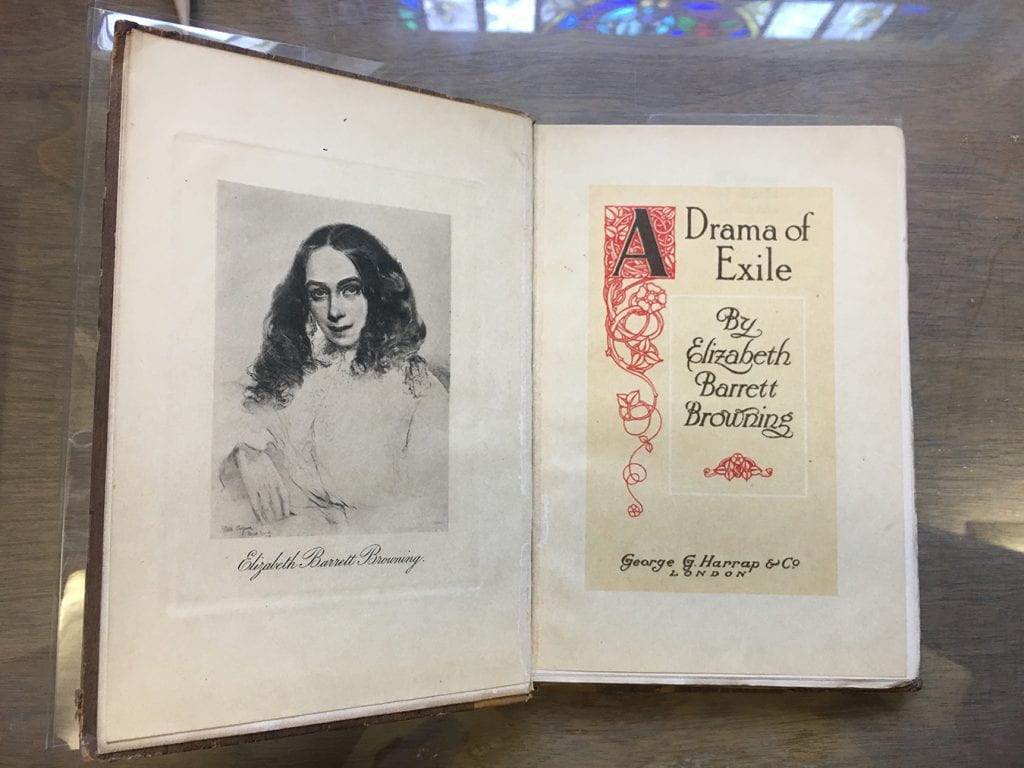

But other writers not only held to their Christian faith; they were moved by it to care for the world around them and create art and poetry that reflected that world’s beauty, fragility, and dignity. One could argue that Elizabeth Barrett Browning acknowledges Arnold’s perspective in A Drama of Exile. Written as a theatrical narrative of Adam and Eve, A Drama of Exile explores the broken relationship between nature and humanity as a consequence of the fall and expulsion from the Garden of Eden. At one point, Eve laments her separation from nature, remembering what she had been in the Garden:

…was I not, that hour,

The lady of the world, princess of life,

Mistress of feast and favour? Could I touch

A rose with my white hand, but it became

Redder at once? (72-73)

In sinlessness, Eve’s presence made nature more fully itself—the roses more red, the grass more green, the leaves of the trees more quivering with life, the birdsong more glad. In turn, she was more herself as well, more “princess of life, / Mistress of feast and favour.” Eve’s separation from God places her at odds with the natural world, limiting its capacity to communicate divine grace.

It is precisely because of this distance that poets like Barrett Browning must remind us through their poetry that nature has its own unique relationship with God, and that the common material of the world around us is also more than material. The distance incurred by the fall keeps God’s presence in the ordinary world from being self-evident. In her introduction to A Drama of Exile, Barrett Browning argues against those who would separate religious concerns from common life, “As if life were not a continual sacrament to man, since Christ brake the daily bread of it in His hands!… As if the word God were not, everywhere in His creation, and at every moment in His eternity, an appropriate word!” (6).

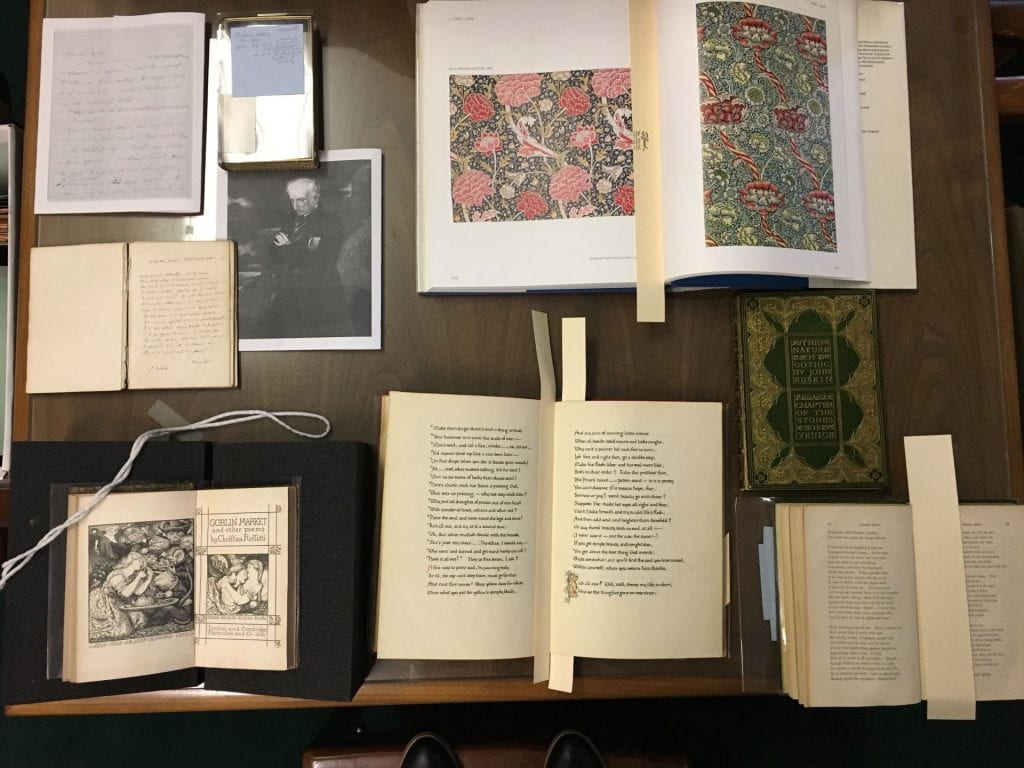

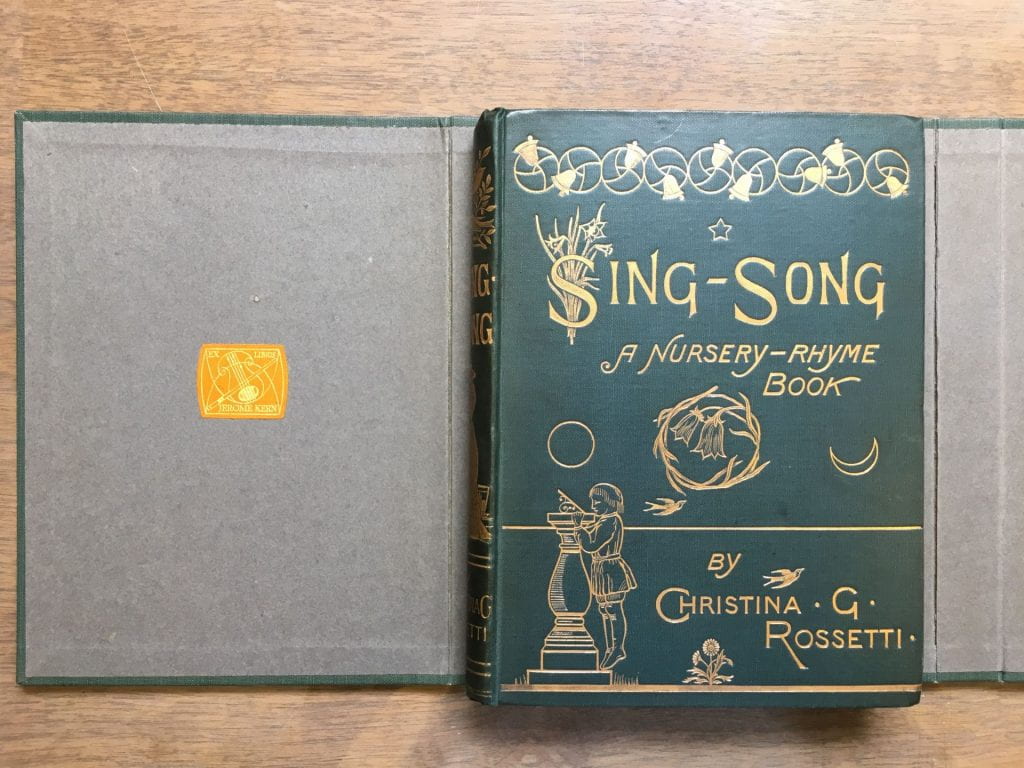

Poets like Barrett Browning who wished to speak prophetically on the state of nature in nineteenth-century imagination drew heavily on William Blake’s poetic works. Blake’s familiar poem, “The Lamb” from Songs of Innocence and Experience, is one such reminder, not only that God made the “Little Lamb,” but that “he calls himself a Lamb” (11). The poem is a gentle, childlike reminder that nature shares in God’s blessings, and that all of God’s creatures are his children—not humanity alone. God can be known and understood by humanity through his other creatures.

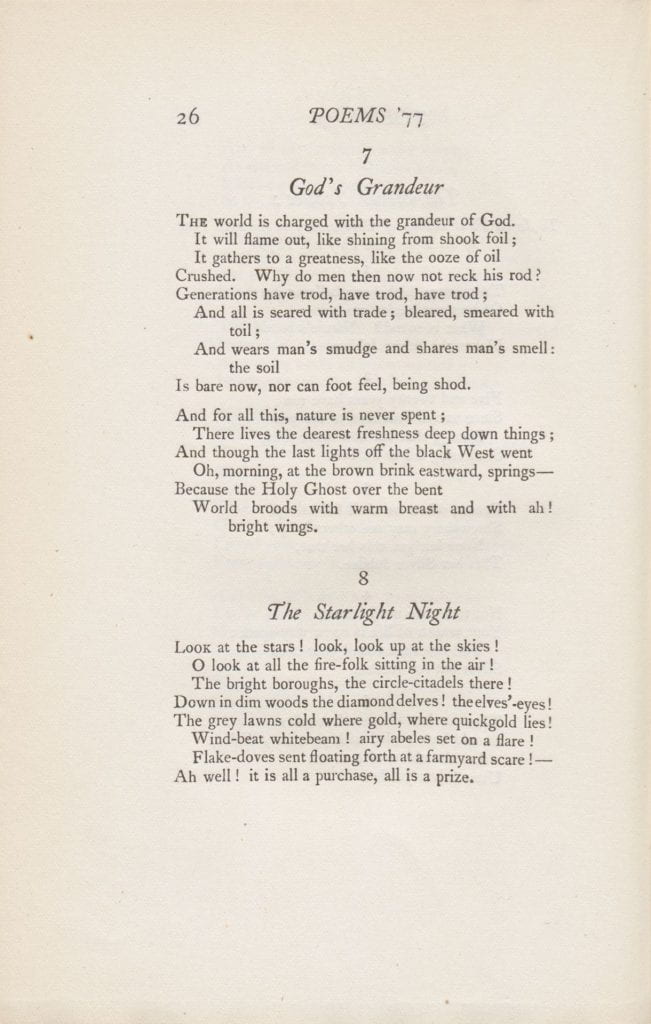

Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “God’s Grandeur,” from Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1st Edition. London: Humphrey Milford, 1918.

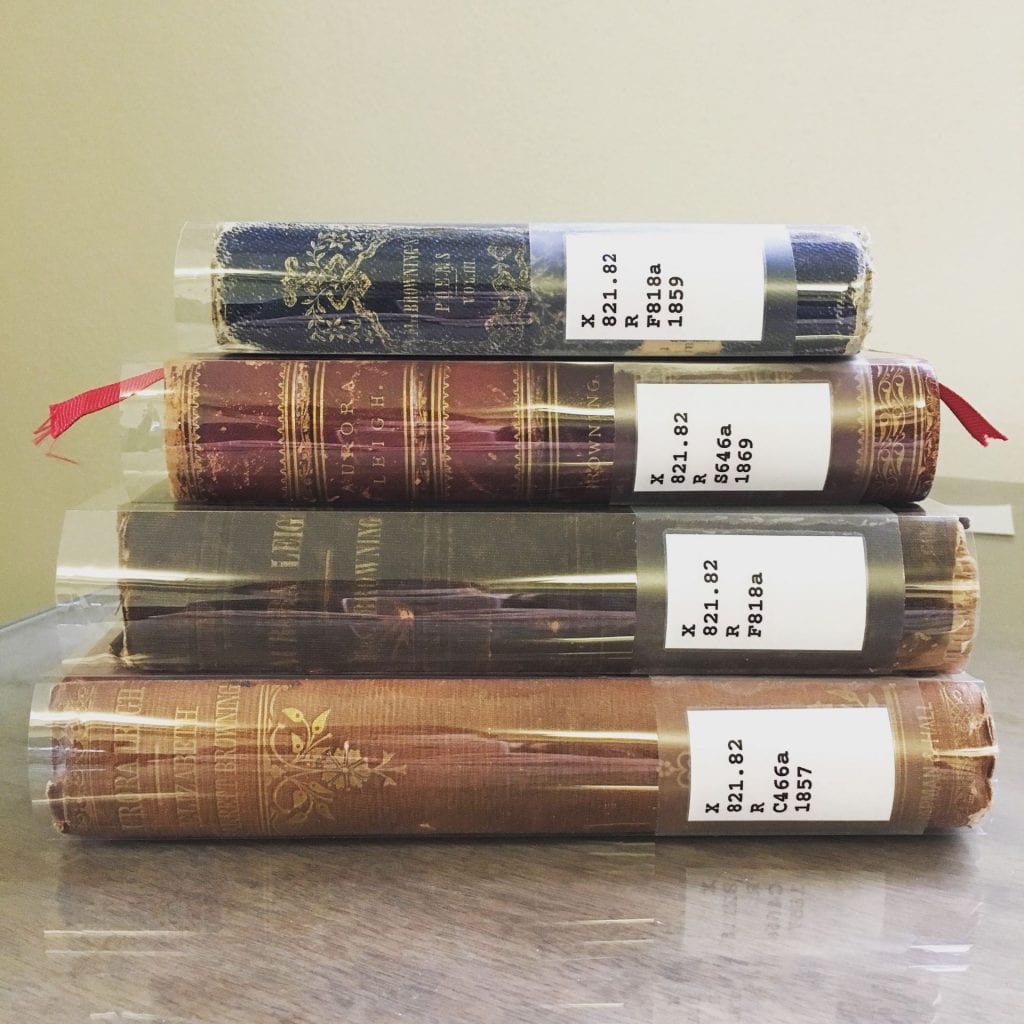

Much later in the century, Gerard Manley Hopkins expands beautifully on this idea in his poem “God’s Grandeur.” In it, he describes how the whole earth is “charged with the grandeur of God,” but that we fail to feel his presence because “the soil / Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod” (26). This line echoes the narrative in Exodus in which God commands Moses to remove his sandals before approaching the bush burning with divine presence. The ABL’s current exhibition displays Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s prose novel Aurora Leigh, showing the famous passage quoted in the exhibit’s title: “Earth’s crammed with heaven, / And every common bush afire with God: / But only he who sees, takes off his shoes” (304). Christina Rossetti’s poem “Tread Softly,” from A Pageant and Other Poems is displayed next to Aurora Leigh, which also alludes to the Mosaic narrative: “Tread softly! All the earth is holy ground. / It may be, could we look with seeing eyes, / This spot we stand on is a Paradise” (153). In Hopkins’s poem, our failure to “tread softly” is directly related to our excessive concern with false progress. We have stripped the soil of its fruitfulness and beauty through “trade” and “toil”—both consequences of the fall, like Eve’s distance from the created world—and in the process we’ve “shod” our feet as well.

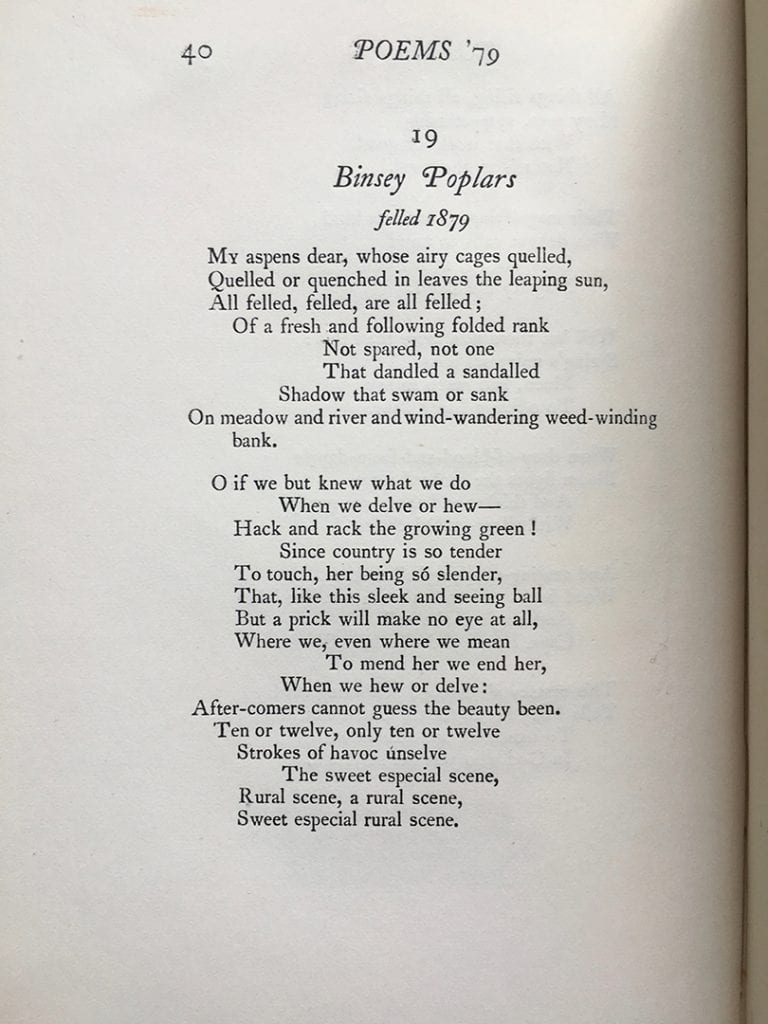

Hopkins’s poem ends in confidence, however, that “nature is never spent.” Looking back with twenty-first-century hindsight, it’s difficult to have such a hope. His poem “Binsey Poplars,” featured early in the exhibition, seems more honest about the irretrievable loss of nature as a result of human carelessness and destruction. To have hope, we need to take more seriously the possibility that the “grandeur of God” lies within all of nature. We need to believe with Barrett Browning that our deepest humanity is found in recognizing our participation in the natural world, not in setting ourselves at odds with it. Until then, it’s small wonder that Arnold’s poem rings true for so many readers. We have failed to take off our shoes.

Read more in this series of blog posts about the exhibit “‘Every common bush afire with God’: Divine Encounters in the Living World“: