By Eric Stoykovich, PhD, of the Watkinson Library, Trinity College (Hartford, Connecticut)

The Armstrong Browning Library (ABL) at Baylor University is responsible for curating The Browning Letters project, a collaboration to make the correspondence written by and to the Victorian poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning digitally viewable in high-resolution. Recently, the Watkinson Library at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, contributed to this effort by digitizing several unique items in its manuscript holdings with the main purpose of making them widely available for the first time through The Browning Letters project. Within its large holdings of rare books, manuscripts, and archives, the Watkinson Library, a public research library, preserves a number of collections which touch upon the lives and works of the Brownings. The two now-digitized autograph letters penned by the poets – Elizabeth’s November 1836 letter, written in London before her marriage, is addressed to publisher Samuel Carter Hall, and Robert’s July 1862 letter to Frances Davenport Perkins, written after his wife’s death – reside in separate but related collections at the Watkinson.

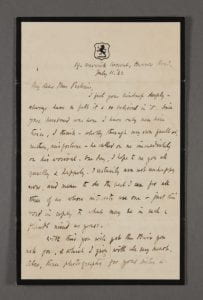

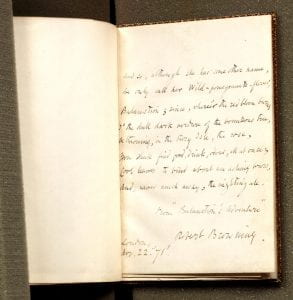

Elizabeth B. Browning to Samuel Carter Hall, November 22, 1836

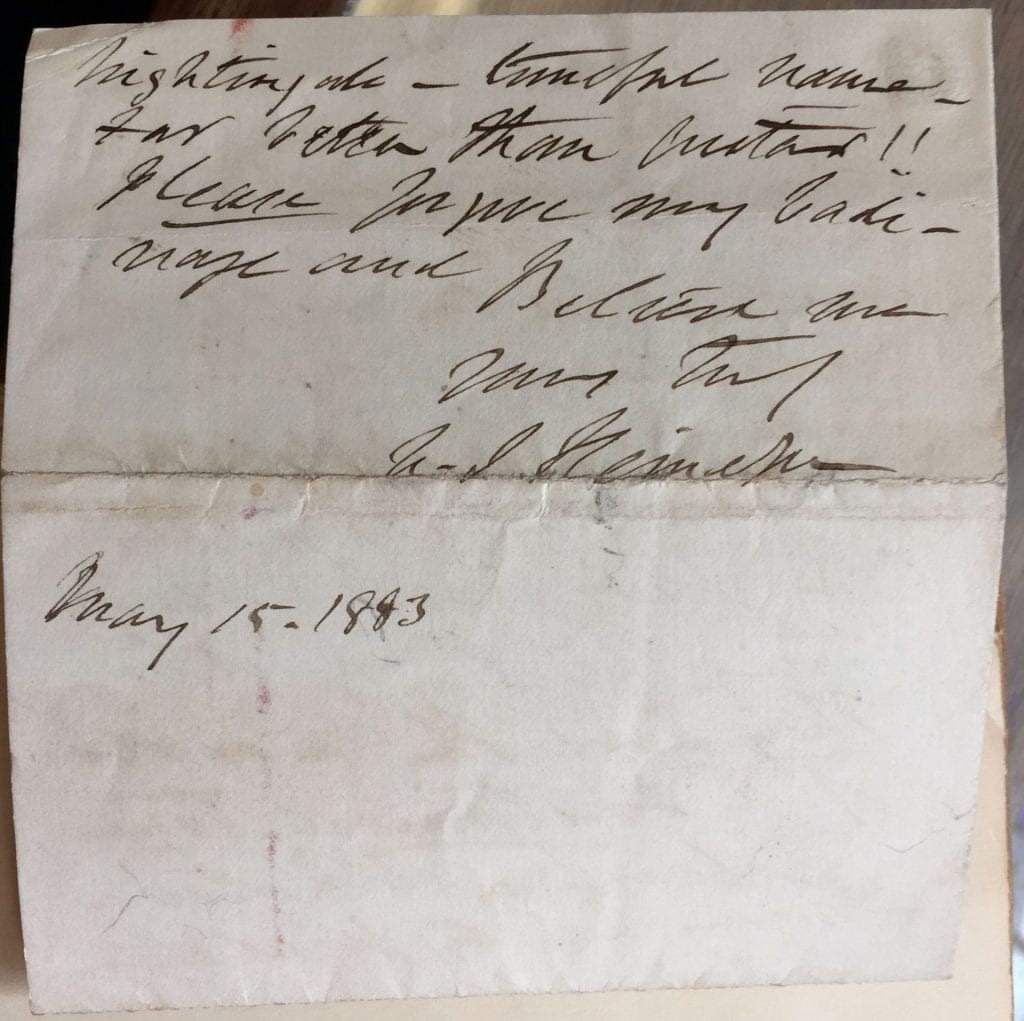

Elizabeth’s letter to Hall, who was then in London working as editor of The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, deals partly with two poems – “The Romaunt of Margret” and “The Poet’s Vow” – which Hall had just published. Elizabeth apologized for the appearance of her unresponsiveness to Hall’s previous letters, as well as her inability to enclose forthwith “the poem I am at present engaged upon,” namely “The Seraphim.” Instead she substituted “one of a simpler character,” probably “The Island,” published in January 1837 in the same periodical. Elizabeth’s letter is part of the William R. Lawrence Papers, an autograph collection assembled by Lawrence (1812-1855), son of industrialist Amos Lawrence. It is unknown how they arrived at the Watkinson.

Even if comprised of just 1 cubic feet of material, the Lawrence Papers bring together quite a few notable British literary figures, including Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Her November 1836 letter appears to have entered the Lawrence collection in March 1852 directly from Samuel Carter Hall. Someone, perhaps Lawrence himself, then took time to write brief descriptions of the individuals whose autographed letters are represented in the collection. Portraying Elizabeth as a highly unusual poet (even in an era of published females), that commentator praised the poet’s work:

“The Poetess, resides in London. Her productions are unique in this age of lady authors. Her excellence is her own; her mind is colored by what it feeds on; the fine tissue of her flowing style comes to us from the loom of Grecian thought. She is the learned poetess of the day, familiar with Homer, and Aeschylus and Sophocles.”

*****

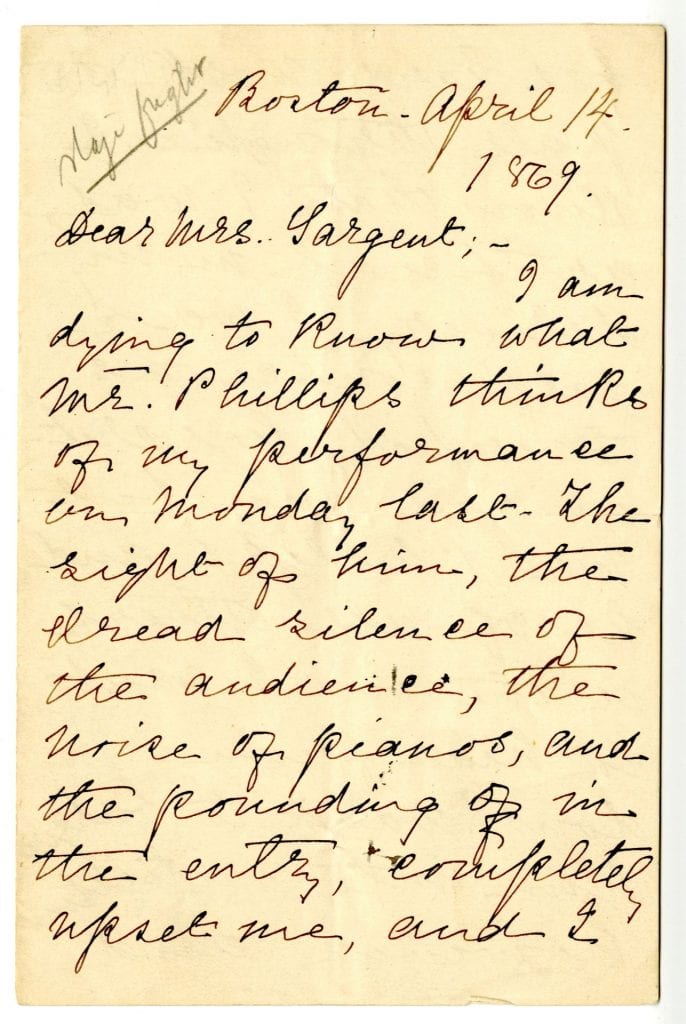

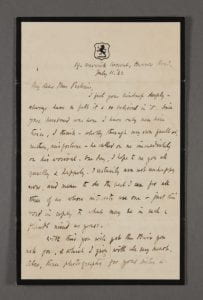

Robert Browning to Frances Davenport Perkins, 11 July 1862

Robert Browning’s July 11, 1862, letter is part of the Watkinson’s British Notables Collection, which also includes letters and manuscripts penned by clergy, soldiers, and authors such as William Makepeace Thackeray, George Bernard Shaw, Charlotte M. Yonge, and William Cobbett. It seems to have been partly the creation of the aforementioned Samuel Carter Hall (1800–1889) and his wife, Anna Maria Hall (née Fielding, 1800–1881), both noted authors in their day.

Browning’s letter was written to Frances Davenport Perkins (née Bruen, 1825–1909), then residing at Rome with her husband, Charles Callahan Perkins, her unmarried sister, Mary Lundie Bruen, and mother, Mary Ann Bruen. As the black border of Browning’s letter indicates, he was still in mourning for the loss of his wife some twelve months earlier: “With this you will get the Hair you ask for, & which I give with all my heart. Also, three photographs for your sister & mother as well as yourself.”

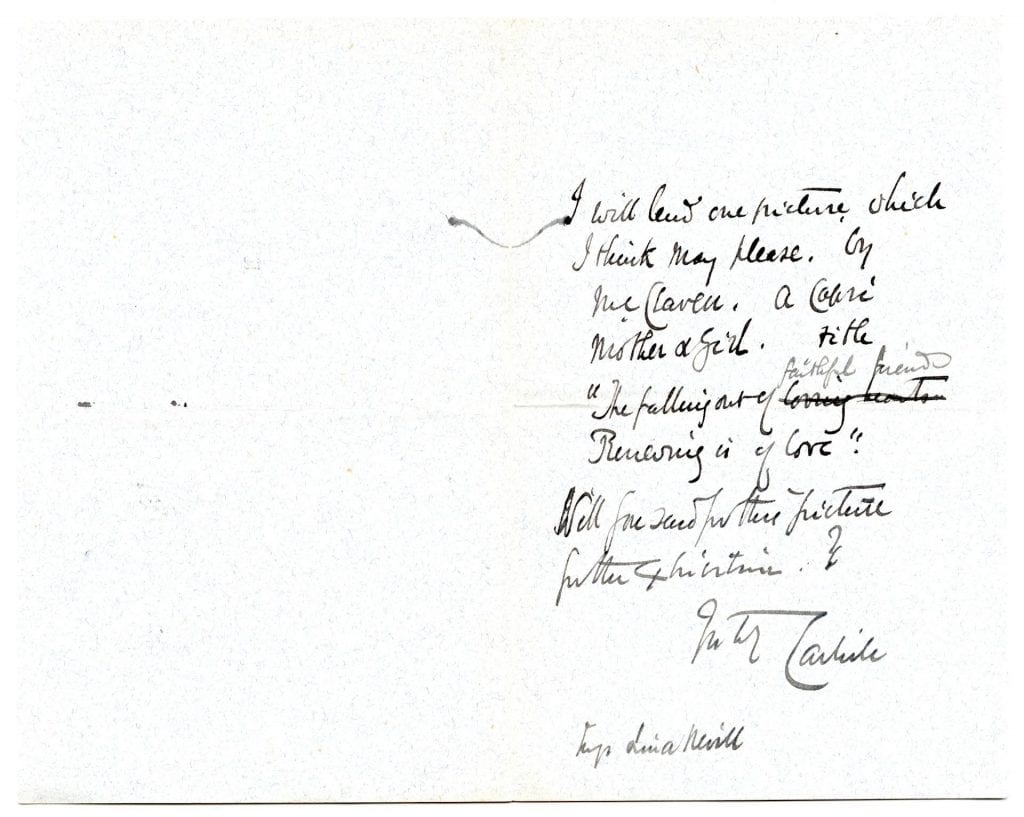

A lock of Elizabeth B. Browning’s hair (in locket) with Satin Box (Browning Guide #H0481)

The “hair” is Elizabeth’s—one of eleven known locks that have surfaced. With the letter is a slip of paper, originally enwrapping EBB’s hair, on which Browning wrote: “For Mrs Bruen—from RB.” The lock is now encased in a garnet-bordered locket, housed in a blue satin box, from the house of Shreve Crump & Low, Boston. One may confidently surmise that the locket was acquired after the family returned to Boston following the American Civil War. The Perkinses and Bruens disembarked from the “S.S. Russia” in New York City on June 29, 1869, the eighth anniversary of Mrs. Browning’s death (Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, NY, 1820-1897, June 29, 1869).

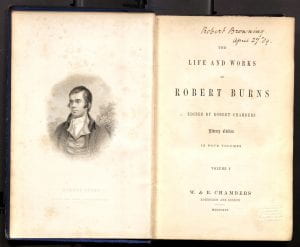

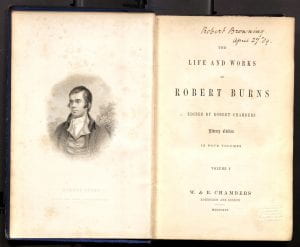

Robert Browning’s owner’s inscription, dated April 27, 1889, less than eight months before Robert Browning’s death on December 12, 1889.

The locket and box with Elizabeth’s hair, the letter from Robert, and one of the three photographs of Robert which he sent to Mrs. Perkins, all came to the Watkinson Library in a single donation in early 1973, along with a number of other important literary works from the Victorian era and the twentieth century. The donor, Arthur Milliken, former headmaster of a private school in Simsbury, Connecticut, also gave 27 first editions of Robert Browning’s works, including the eight-volume “Bells and Pomegranates,” as well as Browning’s own inscribed copy of a set of “Life and Works” by Robert Burns. A Yale graduate, Milliken nevertheless thought that his collection would be treasured more by a smaller college like Trinity (Hartford Times, March 1973).

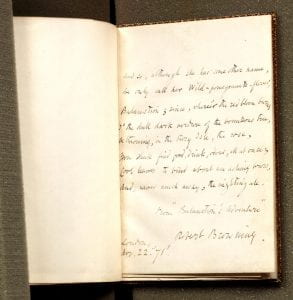

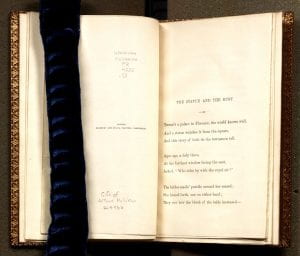

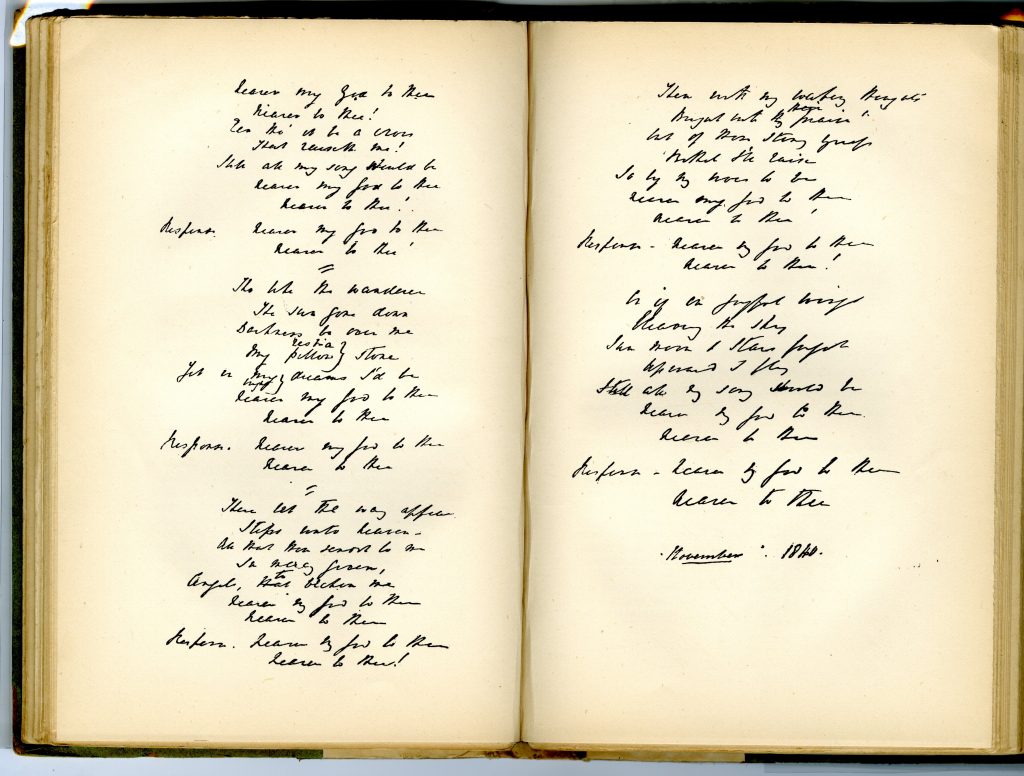

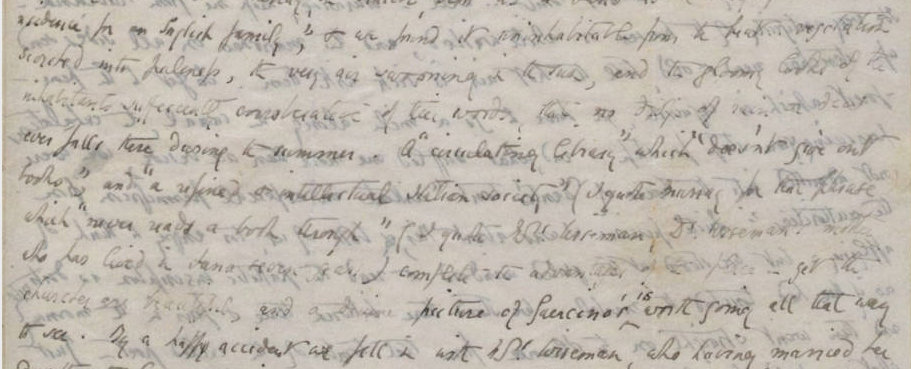

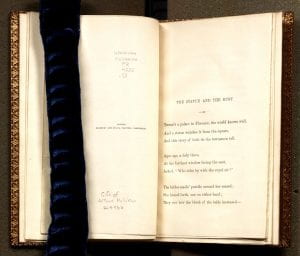

Robert Browning’s “Balaustion’s Adventure” (1871), in The Statue and the Bust (copy printed after 1880).

While the manuscripts that Milliken donated to the Watkinson Library were apparently added to the mixed-provenance British Notables Collection, the over 100 books he donated were catalogued separately. One of Milliken’s books is especially intriguing: a copy of “The Statue and the Bust” contains eight lines of Robert Browning’s “Balaustion’s Adventure,” dated November 22, 1871, authentically handwritten by Browning himself, while in London, and tipped into the front matter. However, the printed and bound parts of the book actually consist of a skillful forgery of The Statue and the Bust by famous Victorian hoaxer Thomas J. Wise. The authentic manuscript may have been placed strategically to distract attention from the post-1880 print forgery, later detected by its type and its esparto with chemical wood paper.

Robert Browning, The Statue and the Bust (forged copy by Thomas J. Wise, after 1880)

*****

The Watkinson Library in Hartford, Connecticut, serves as a public research library, as well as the rare book library, special collections, and archives of Trinity College. Started in 1858 as a non-circulating reference library for all citizens of Hartford and other visitors to Connecticut, the Watkinson Library has been transformed by its 70-year partnership with Trinity College into a place for many types of instruction, research, and collaboration with local community members and global scholars. It has a number of collecting strengths, particularly in books of hours, incunables, Americana, ornithology, American Indian languages, Hartford socialites and authors, early 20th-century posters, artists’ books, and college records which date prior to 1823, the founding of Trinity College. The vision of the Watkinson Library is to create a welcoming space for all to encounter and interact with the cultural materials held by it, and to facilitate creative and intellectual production based on or inspired by its collections.

The first four images above are courtesy of Amanda Matava, Digital Media Librarian, Trinity College Library, who deserves thanks for the high-quality photography of multi-dimensional artifacts. The author scanned the final three images. The author would also like to thank Philip Kelley for his editorial and research assistance.

*****

The Armstrong Browning Library is grateful to Trinity College for its participation in The Browning Letters project. Institutions and individuals interested in making their Browning letters accessible by joining this project can contact ABL Director Jennifer Borderud.