By Melinda Creech

Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, more commonly known as the White Star Line, was a prominent British shipping company. Founded in 1845, The White Star Line, operated a fleet of clipper ships that sailed between Britain, Australia, and America. The ill-fated Titanic was perhaps their most famous ship. The Armstrong Browning Library has a few connections to the Titanic. One connection relates to a set of postcards that disappeared with the Titanic and another relates to the author of the hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” the song that was purportedly playing as the Titanic sank. The Armstrong Browning Library’s collection includes a letter with the White Star logo in its heading and several letters written on board ships or while individuals were preparing to board ships. The letters, written between 1841 and 1912, are lines from people who were passengers on SS (Steamer Ships), RMS (Royal Mail Steamers), or HMS (Her Majesty’s Ship). It is interesting to note that one of the first purposes of steamers crossing the Atlantic was to deliver the mail. These lines, written from steamer ships, may shed some light on the adventure and danger presented by steamer travel in the late nineteenth century.

This first post is directly connected to the Titanic and tells the story of a unique link between Robert and Elizabeth Browning and the sunken Titanic.

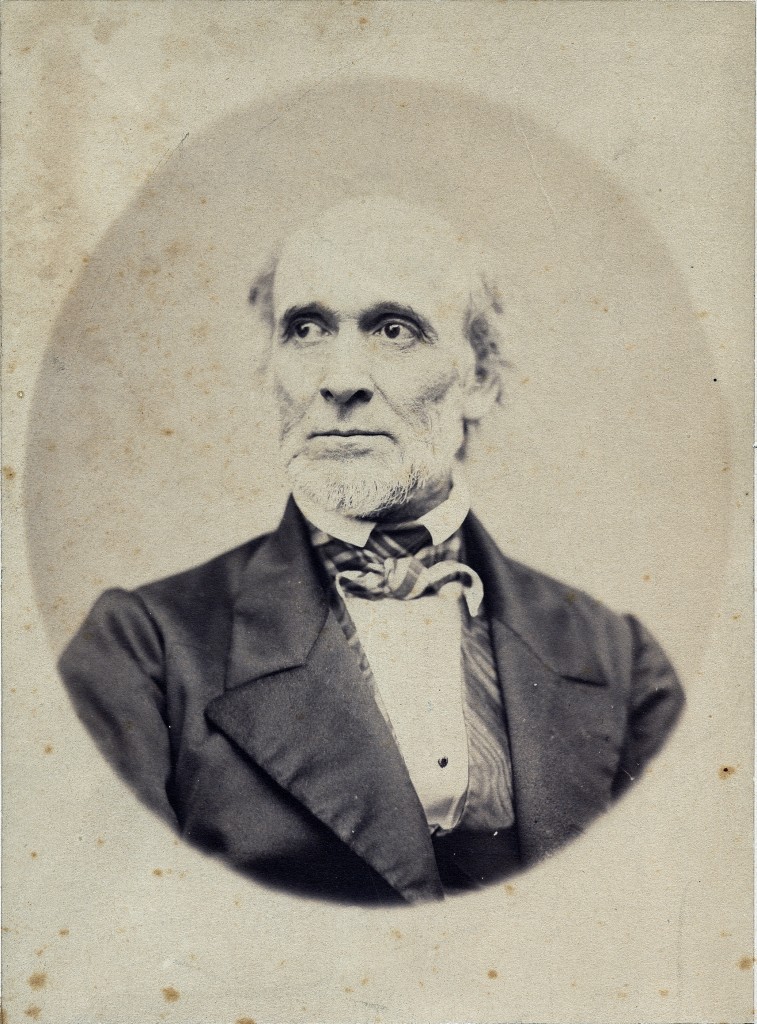

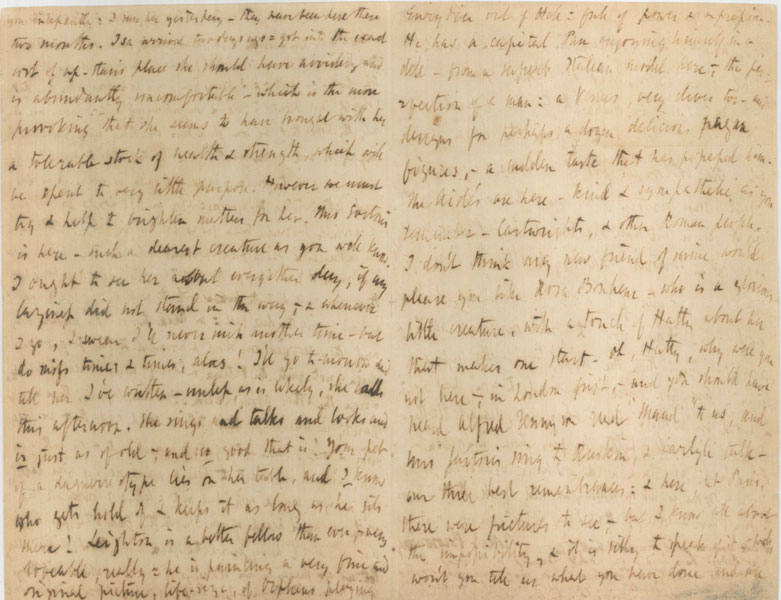

In the spring of 1912, one hundred years after the birth of Robert Browning, William Lyon Phelps, Yale professor and Browning scholar, and his wife made a trip to the little Italian town of Fano. Dr. Phelps and his wife had boarded the S. S. Cleveland on 1 July 1911 for their second sabbatical trip from Yale University, visiting England, Sweden, Russia, Germany, France, and were now ending up their travels in Italy. Dr. Phelps and his wife knew that the poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning had visited Fano in the summer of 1848. The Phelpses travelled there with the expressed purpose of walking in the poets’ footsteps.

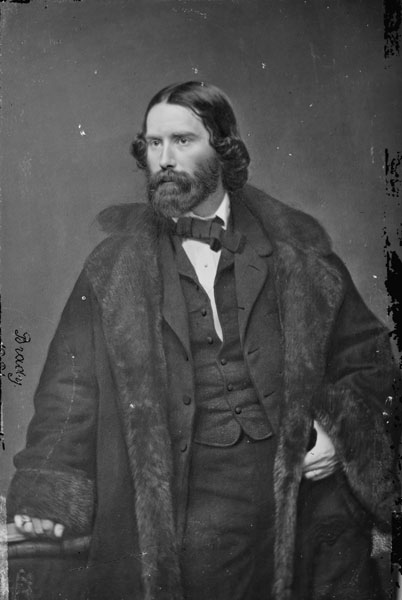

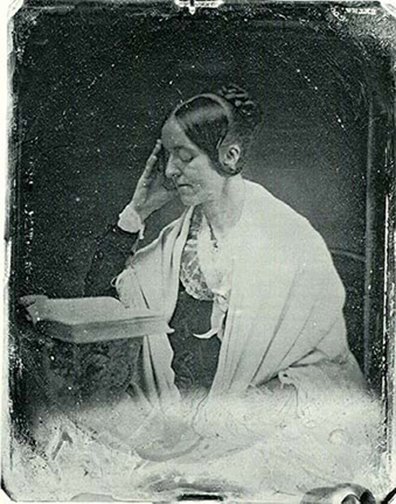

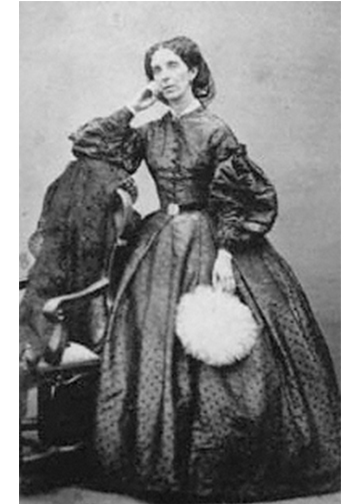

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, aged 47. Oil painting by Thomas Buchanan Read, Florence, November 1853. Robert Browning, aged 41. Oil painting by Thomas Buchanan Read, Rome, November 1853.

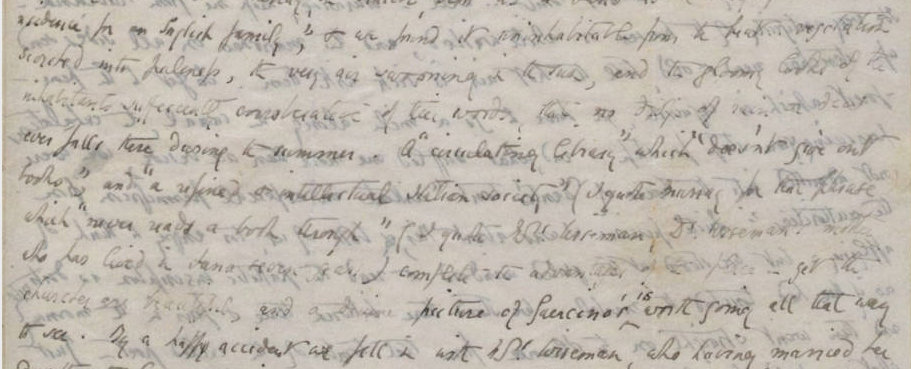

In the summer of 1848 the Brownings had travelled to Fano, Italy, hoping the cool sea breeze of the east coast of Italy would provide a respite from the stifling heat they had been experiencing in their home in Florence. They found Fano even hotter than Florence. Looking for some shade they entered the Church of San Agostino and discovered a large painting, The Guardian Angel, by a seventeenth-century artist known as Guercino. In a letter to Mary Russell Mitford, 24 August [1848], Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote:

we found it uninhabitable from the heat.. vegetation scorched into paleness, the very air swooning in the sun, and the gloomy looks of the inhabitants sufficiently corroborative of their words, that no drop of rain or dew ever falls there during the summer . . . —yet the churches are beautiful, and a divine picture of Guercino’s is worth going all that way to see.

When the Brownings returned to their hotel in Ancona, Robert composed a poem inspired by the painting, which he titled “The Guardian Angel: A Picture at Fano.”

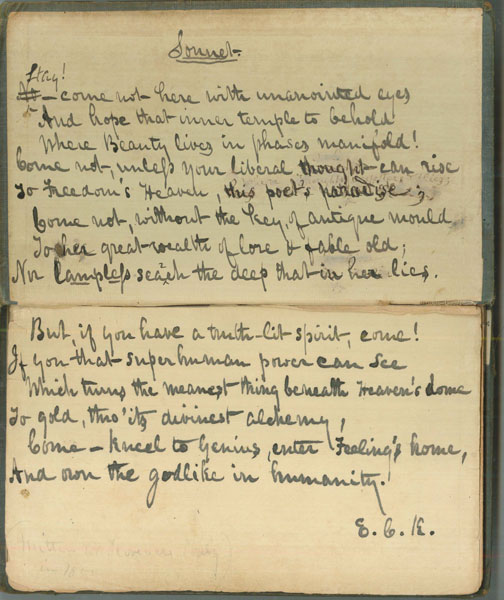

I.

Dear and great Angel, wouldst thou only leave

That child, when thou hast done with him, for me!

Let me sit all the day here, that when eve

Shall find performed thy special ministry,

And time come for departure, thou, suspending

Thy flight, mayst see another child for tending,

Another still, to quiet and retrieve.

II.

Then I shall feel thee step one step, no more,

From where thou standest now, to where I gaze,

—And suddenly my head is covered o’er

With those wings, white above the child who prays

Now on that tomb—and I shall feel thee guarding

Me, out of all the world; for me, discarding

Yon heaven thy home, that waits and opes its door.

III.

I would not look up thither past thy head

Because the door opes, like that child, I know,

For I should have thy gracious face instead,

Thou bird of God! And wilt thou bend me low

Like him, and lay, like his, my hands together,

And lift them up to pray, and gently tether

Me, as thy lamb there, with thy garment’s spread?

IV.

If this was ever granted, I would rest

My head beneath thine, while thy healing hands

Close-covered both my eyes beside thy breast,

Pressing the brain, which too much thought expands,

Back to its proper size again, and smoothing

Distortion down till every nerve had soothing,

And all lay quiet, happy and suppressed.

V.

How soon all worldly wrong would be repaired!

I think how I should view the earth and skies

And sea, when once again my brow was bared

After thy healing, with such different eyes.

O world, as God has made it! All is beauty:

And knowing this, is love, and love is duty.

What further may be sought for or declared?

VI.

Guercino drew this angel I saw teach

(Alfred, dear friend!)—that little child to pray,

Holding the little hands up, each to each

Pressed gently,—with his own head turned away

Over the earth where so much lay before him

Of work to do, though heaven was opening o’er him,

And he was left at Fano by the beach.

VII.

We were at Fano, and three times we went

To sit and see him in his chapel there,

And drink his beauty to our soul’s content

—My angel with me too: and since I care

For dear Guercino’s fame (to which in power

And glory comes this picture for a dower,

Fraught with a pathos so magnificent)—

VIII.

And since he did not work thus earnestly

At all times, and has else endured some wrong—

I took one thought his picture struck from me,

And spread it out, translating it to song.

My love is here. Where are you, dear old friend?

How rolls the Wairoa at your world’s far end?

This is Ancona, yonder is the sea.

Standing before the painting on Easter day, 7 April 1912, in the church of San Agostino, Phelps wondered why few Browning enthusiasts visited Fano. To encourage such visits, Phelps instituted the Fano Club. Anyone could become a life member by visiting Fano, seeing the painting, and sending him a picture postcard postmarked from Fano. He and his wife bought seventy-five postcards and addressed them to various friends in America. Unfortunately, the postcards never reached their destinations as they were among the cargo on board the Titanic.

But in spite of the first failed attempt, the idea caught on. In his Autobiography with Letters, published in 1939, Phelps reported that over 500 scholars, students, and lovers of Browning had been inspired to make the pilgrimage.

The administration of the Fano Club was passed on to Dr. A. J. Armstrong (1873-1954), founder of the ABL, after the death of William Lyon Phelps in 1943, and has been carried on by each succeeding library director. Today there are over 200 members of the Fano Club from around the world. Each year members are invited to the ABL around May 7, which is Robert Browning’s birthday, for a dinner and a meeting. Members share stories about seeing the painting (now in the Civic Museum in Fano) and the youngest member present reads “The Guardian Angel: A Picture at Fano” to the group.

Perhaps one day those postcards will be found among the remains of the shipwrecked Titanic.