Kenna Lang Archer recently presented a lecture hosted by The Texas Collection, “The Brazos River and the Baylor Archives: A History of Floods and Droughts, a Story of Resilience and Ideals.” Archer has been coming to The Texas Collection for many years to research the Brazos River and its environmental impact—she even earned one of our Wardlaw Fellowships for Texas Studies.

So we thought she would be a perfect candidate to share some of what she has learned about special collections research. Archer has a heart for educational outreach and far too much to say to fit into one blog post, so this is the first installment in a three-part series, “A User’s Guide to The Texas Collection.”

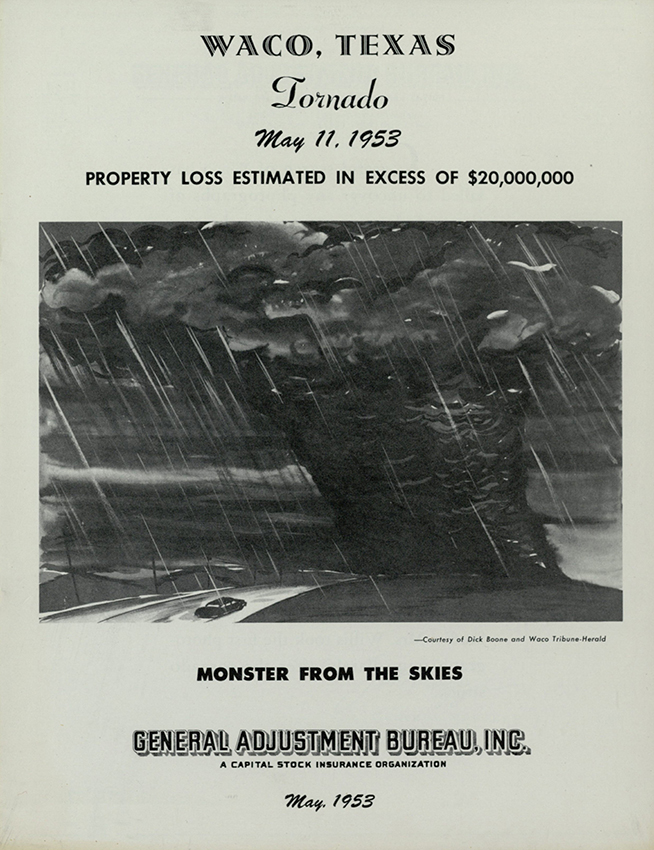

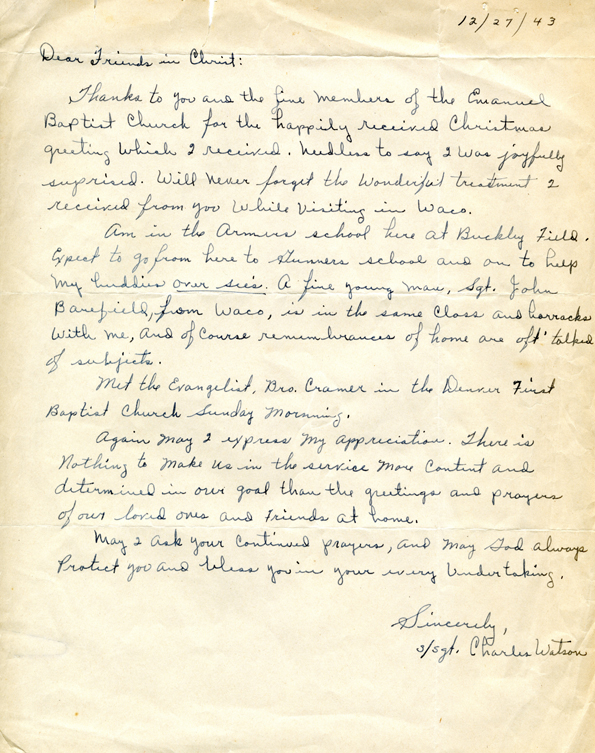

I recently completed a study on the Brazos River, and while I loved the topic, it wasn’t always easy to find sources for my research. People living in Waco in 1856 rarely sat down with the explicit goal of writing about water—“Dear Robert. Old Man River is especially murky today…I can think of nothing but mud pies as I stare into its depths (which total 15 feet, 100 yards north of Waco).” Ditto with individuals living in other cities at other periods. Instead, people wrote about matters of immediate importance—crops, kin, wars, etc.

This intellectual inertia is hardly unique to me. Most researchers, at one time or another, have encountered a similar problem. The obvious search words are sometimes not enough, and in those moments, it becomes necessary to follow alternative pathways. Fortunately, in that disorder is potential. I once used the record books of the Waco Bridge Company to determine the supplies used in the Waco Suspension Bridge, which incorporated trees that had been logged locally. These financial records, in other words, told me about the species that populated Cameron Park in the late 1800s, a park that itself sits along the Brazos.

Sometimes, the sources simply are not there, but oftentimes, information can be gleaned from the space between ideas. Search Brazos River but also search intellectually adjacent words—agriculture, Cameron Park, cattle. The use of non-traditional sources and peripheral search terms can be time-consuming, but it results in a richer understanding of the subject, making the intellectual effort more than worthwhile.

Along those same lines, if I could offer one piece of advice to individuals engaged in research, it would be this—get to know the employees of the archives/library.

A good relationship with archivists, curators, librarians, and coordinators is the surest path to a completed project. Likewise, a bad relationship with these same individuals (or no relationship at all) is a sure way to become mired in more material than you could ever process. That is the dirty secret of historic research—it is impossible to track every lead, tumble down every rabbit hole, follow every hunch. A bittersweet blessing: scholars, with few exceptions, have access to far too many letters, diaries, and photographs to peruse every line of thought. And, yet, projects can hinge on a single piece of evidence. What is an industrious scholar to do? Engage the experts.

Special collections employees can recommend finding aids, suggest search words, pull off-site material, or even let you know when collections are unavailable due to routine maintenance. Over the last five years, the employees of the Texas Collection made my project possible in a very literal sense. Amie Oliver suggested nineteenth century promotional booklets that did not mention the Brazos but nevertheless provided insight into the movement of immigrants; Geoff Hunt tracked down a panoramic photograph of industrializing Waco that unveiled flood patterns; Tiffany Sowell pulled manuscripts from the turn of the century that exposed urban growth patterns. Archival resources are not limited to pen and ink; get to know the men and women who work in the stacks.

See our staff listing to learn who those folks in the stacks are at The Texas Collection! And stay tuned for the August entry in this series.

Archer is an instructor in the history department at Angelo State University. She earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Baylor and then her doctorate at Texas Tech University. You can learn more about her research on her website, www. kennalangarcher.com.