Each month, we post an update to notify our readers about the latest archival collections to be processed and some highlights of our print material acquisitions. These resources are primed for research and are just a sampling of the many resources to be found at The Texas Collection!Continue Reading

Republic of Texas

Texas over Time: Texas State Capitols

Texas has changed quite a bit over the years, as is readily seen in our vast photograph and postcard collections. To help bring some of those changes to life, we’ve created a “Texas over Time” series of GIFs that will illustrate the construction and renovations of buildings, changing aerial views, and more. Our collections are especially strong on Waco and Baylor images, but look for some views beyond the Heart of Texas, too.

- Along with Washington-on-the-Brazos and Galveston, Harrisburg served as one of Texas’ temporary capitals. President David G. Burnet convened the provisional government at the John R. Harris home (image 1) in 1836.

- Columbia was the first capital of an elected government of the Republic of Texas, but that lasted only from October-December 1836. The second capital of the Republic of Texas was in Houston, Texas (1837–1839, 1842). Sam Houston’s executive mansion and Harris County court house is pictured in image 2.

- The modern-day Capitol in Austin, Texas, was constructed between 1882 and 1888 after there being a few prior buildings. A building commission was implemented, and Elijah E. Myers won the competition for the architecture design. Construction began in 1882, the corner stone was laid March 2, 1885 and it was ready for use in 1888. The building was built entirely of “sunset red” granite from quarries near Marble Falls, Texas.

- At its initial construction, the capitol had 392 rooms, 924 windows and 404 doors. It is 311 feet tall, beating out the U.S. Capitol (288 feet), just by the height of the “Goddess of Liberty” statue that stands atop the dome.

- The original zinc Goddess statue weighed almost 3,000 pounds. In 1986, it was taken down and replaced by a lighter aluminum version. The statue is now on display at the Bob Bullock State History Museum.

Image 1: John R. Harris home, Harrisburg, Texas (one of several Texas capitol locations in 1836)

Image 2: Sam Houston’s executive mansion in Houston, and the second capital of the Republic of Texas (1837-1839, 1842)

Image 3: First capitol in Austin (and the only capitol for the Republic of Texas and the State of Texas), 1839–1856

Image 4: Second capitol in Austin, built 1856, burned 1881

Image 5: Third capitol in Austin, completed 1888

Sources

Handbook of Texas Online, William Elton Green, “Capitol,” accessed April 21, 2016, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ccc01.

Handbook of Texas Online, John G. Johnson, “Capitals,” accessed May 12, 2016, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/mzc01.

“The Goddess of Liberty.” SenateKids. Texas Senate Media Services, 1998. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.

GIF and factoids by Haley Rodriguez, archives student assistant. See these Texas State Capitol images in our Flickr set.

Documenting the Parker Family Story at The Texas Collection (Part 3)

For the past two weeks, we’ve been writing about the Parker family—see Part 1 and Part 2. Last week’s post was about the preservation of Old Fort Parker. Today we continue the story with the Parker family’s work to preserve its historical documents—what is now the Jack and Gloria Parker Selden collection, housed at The Texas Collection.

The story of preserving Parker family materials through time is impressive in its own right. With many documents in the collection dating back to the 19th century, it is remarkable that so many of these papers survived. Family historians faithfully stored and studied the documents and made sure the materials endured for the next generation of the family. Now, by giving them to The Texas Collection, these documents are preserved and accessible for the public to view and research.

Materials in this collection were assembled, collected, and preserved by three distinct groups in the Parker family: Joseph and Araminta Taulman, Lee Parker Boone, and Jack Selden, though many other Parker family members contributed to the preservation of their family history, including Joe Bailey Parker and Ben J. Parker. Each of the three major preservation groups represents a different generation in the Parker family history, and each contributed different research materials and collecting emphasis to the collection.

It seems that family members began gathering historical documents relating to family history very early in their time in Texas. By 1854, the materials were stored in a container the family has referred to as the “blue box” by Dan Parker, grandson of Daniel Parker. This box of documents was added to over time and passed down through the family. It eventually came to Jack Selden and contained most of what is now Series I, the oldest materials in the collection.

Joseph and Araminta Taulman were active in Texas public history in the 1930s. Araminta was the great-great-granddaughter of Daniel Parker, patriarch of the Parker family in the 1830s. While the Taulmans created some materials now in the Jack and Gloria Parker Selden collection, most of the Taulman papers are now in the Joseph E. Taulman Collection at the Briscoe Center for American History at The University of Texas at Austin.

Lee Parker Boone, born in 1891, focused on collecting and describing Parker genealogy information for much of his life. Boone was a court reporter in Midland, Texas. In the Selden collection, many of the letters inquiring about family trees and giving information about possible family relationships were from or to Boone.

Jack Selden was born in 1929 and graduated from Palestine High School in Texas. After graduating from George Washington University, he served in the United States Air Force as a navigator and speechwriter for 21 years, eventually becoming a lieutenant colonel. Returning to Palestine, he became a civil trial assistant. In 1985, he became mayor of Palestine, serving three terms.

At some point, Selden became the historian of the Parker family and faithfully preserved an increasingly large collection of documents, photographs, and other materials containing his research on the topic, plus the work of Lee Boone, selections from Joseph Taulman, and others who contributed to preserving the Parker family story. With these resources, Selden wrote and published a book on the Parker family in Texas history. Return: The Parker Story, published in 2006, documents the Parker family’s arrival in Texas, and traces their history through Cynthia Ann Parker, Quanah Parker, and others, up to the Parker family reunions today. This past year, Selden donated this collection of materials to The Texas Collection.

Jack Selden also wrote and performed in the “Telling of the Tales,” a dramatic reading of the Cynthia Ann Parker story. Other Parker family members also participated in the production. This drama was performed several times for the public, both at Old Fort Parker in the early 1980s and at Pilgrim Baptist Church near Elkhart, Texas. Programs and scripts from “Telling of the Tales” performances can be found in the Selden collection.

This concludes our series celebrating the Jack and Gloria Parker Selden papers arrival at The Texas Collection. Mark your calendar for Selden’s lecture: Thursday, February 18, at 3:30 pm in the Guy B. Harrison Reading Room of The Texas Collection, located in Carroll Library at Baylor University. If you can’t make the lecture, follow us on Twitter—we’ll be live-tweeting the event at #ParkerFamilyTX.

Sources:

Find a Grave, Inc. “Lee Parker Boone.” Memorial #22788886. Databases. Accessed February 8, 2016.

Joseph E. Taulman Collection, 1783-1994, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

Selden, Jack. Return: the Parker Story. Palestine: Clacton Press, 2006.

Documenting the Parker Family Story at The Texas Collection (Part 2)

We recently wrote about the story of Cynthia Ann and Quanah Parker. Today we continue the story by discussing efforts through time to remember their story by preserving Fort Parker.

After the events of the Parker story in Texas—Cynthia Ann’s capture by Comanche, her recapture and return to Texan society, her son Quanah’s role as military leader against the United States army, and his subsequent role as a political leader to help the Comanche on the reservation—the Parker story became a popular one in Texas. (See Part One of this blog series if you need a refresher.) With Texan interest in historic preservation growing due to the impending Texas Centennial in 1936, people began to work towards preserving the site of Parker’s Fort or Fort Parker.

While the original fort was long gone, the site was selected in the 1930s as a work area for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It was decided to build a replica fort, matching as closely as possible the original fort built by the Parkers. Several Parker family members visited the site of replica fort in the 1930s to help verify that it was the site of the original fort. Construction was still underway as the Texas Centennial came and went.

Only a couple of miles away, the same CCC camp built camping and outdoor recreational facilities around a 670 acre lake, formed from building a dam across the Navasota River. While the plan originally called for one site to be named Fort Parker State Park, which would include the replica fort, the lake, and all the recreational facilities, eventually the site was split into two separate areas. Confusingly, the recreation area with the lake became known as Fort Parker State Park, while the replica fort site became known as Old Fort Parker State Historic Site, or just the Old Fort.

In 1941, after years of planning and construction, Fort Parker State Park was opened to the public. Along with fishing, boating, and fireworks, people could also visit Old Fort Parker, where construction was complete on the replica fort.

After many years of use, the replica fort at the Old Fort site was rebuilt in 1967. Both Fort Parker sites were operated by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department until 1992, when the nearby cities of Groesbeck and Mexia, and Limestone County took over operations of the Old Fort. Fort Parker State Park continues to operate as a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department site.

Today, visitors to Old Fort Parker can tour the replica fort, various historic structures from Central Texas, and the visitor center. For research opportunities, patrons can visit The Texas Collection and view materials on the Parker family and Old Fort Parker.

The next post in this series will examine the various creators of the Selden collection. Mark your calendar for Selden’s lecture: Thursday, February 18, at 3:30 pm in the Guy B. Harrison Reading Room of The Texas Collection, located in Carroll Library at Baylor University.

Documenting the Parker Family Story at The Texas Collection (Part 1)

The Texas Collection recently acquired a group of historic documents on the Parker family, including Cynthia Ann Parker and her son Quanah Parker. This amazing collection is one of several record groups on the Parker family already at The Texas Collection. In anticipation of Jack Selden’s February 18 lecture, “Return: the Parker Story,” this blog post will be the first in a series of posts that tell the story of the Parker family in Texas.

Cynthia Ann Parker came to Texas with 38 family members from Illinois in 1833, and the family settled near Groesbeck. By the summer of 1835, the Parkers had a rough wooden fort built that was called Parker’s Fort or Fort Parker. The family tended crops on about 12 miles along the Navasota River, returning as needed to the fort.

By 1835-1836, situations in Texas had changed drastically from when the Parkers first came to Texas. Good relations with local American Indian groups had given way to open hostility, as Texans attacked a Kichai village to recover horses thought to have been stolen. For several weeks, this group of Texans used Parker’s Fort as a base to search surrounding areas for Indian groups that they believed had stolen their horses.

Working relationships with the Mexican government had also deteriorated. Military hero Antonio López de Santa Anna overthrew the previous government, put down rebellions that broke out in various Mexican states, and sent military units to Texas to enforce Mexican law. By 1836, Santa Anna himself was in Texas at the head of a Mexican army to put down a brewing rebellion among the colonists, who spoke openly of independence from Mexico. After a string of Mexican victories, Sam Houston led a Texian army to win the Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836, and the Texas Revolution was over.

Just one month after the Battle of San Jacinto, on May 19, 1836, Parker’s Fort was attacked by an American Indian force of several hundred warriors, long understood by eyewitnesses to be predominantly Comanche. With many of the Parker men out working in the fields, the 30 people in the fort were quickly overwhelmed. Five Parker family members were killed and five others were captured, but the rest escaped. One group of Parker family members, traveling only at night for safety, trekked 90 miles in six nights to the safety of Tinnenville.

One of those captured was Cynthia Ann Parker. Just twelve or thirteen when taken captive, she was adopted into the tribe and became thoroughly Comanche. She became the wife of Peta Nocona, a noted leader in the Naconi band of the Comanche. They had three children, two boys and a girl: Quanah, Pecos, and Topsannah. Peta Nocona was probably killed in the Battle of the Pease River in 1860. Cynthia Ann was captured by Texas Rangers in this battle, and was identified as the Parker’s Cynthia Ann, who had been with the Comanche for almost 25 years. Though she was returned to Texan society, Cynthia Ann never recovered from her capture and made several attempts to escape back to her life on the plains. She died in 1870, and was originally buried in Fosterville Cemetery, Anderson County, but was reinterred in the Post Oak Mission Cemetery near Cache, Oklahoma, in 1910. Cynthia Ann was reburied a final time in 1957 in the Fort Sill Post Cemetery, Lawton, Oklahoma.

Cynthia Ann’s son Quanah Parker became the last major Comanche chief to surrender to United States authorities. A leader in the Quahada subtribe of the Comanche, Quanah for years frustrated the efforts of the United States army to capture his people. After the Comanche defeat in the Battle of Adobe Walls in 1875, Quanah and his people were pursued by the United States army during the Red River War, the last major military campaign in Texas. After their supplies were destroyed, Quanah and his people were forced to surrender, and were taken to the reservation designated for the Comanche and Kiowa in southwestern Oklahoma.

Over time, Quanah adjusted to reservation life and became a very wealthy and influential man. Though increasingly powerful in Indian-government relations, he could not stop the movement to break up the reservations and distribute the land among the individual Indians, who were then forced to sell much of their land by unscrupulous land dealers. Quanah continued his efforts to help his people however he could, including negotiating leases of land to ranchers, which brought in much-needed income for the tribe. After a visit to the Cheyenne Reservation, Quanah became ill and died twelve days later, in 1911. His remains have been moved once, from Post Oak Mission Cemetery in Oklahoma to Fort Sill Post Cemetery, Lawton, Oklahoma.

The next post in this series will focus on the restoration of the Fort Parker historic site, and the final post will examine the various creators of the Selden collection. Mark your calendar for Selden’s lecture: Thursday, February 18, at 3:30 pm in the Guy B. Harrison Reading Room of The Texas Collection, located in Carroll Library at Baylor University.

Sources:

Gwynne, S.C. Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches. New York: Scribner, 2010.

“Fort Parker Massacre.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Parker_massacre. Accessed 27 January 2016.

Handbook of Texas Online. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook. Accessed 27 January 2016.

Selden, Jack. Return: the Parker Story. Palestine: Clacton Press, 2006.

Joseph E. Taulman Collection, 1783-1994, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

“The History.” Old Fort Parker. http://www.oldfortparker.org/The_History_1DLU.html. Accessed 27 January 2016.

Vernon, Cheril. “Selden to be Honored by Library.” Palestine Herald-Press. November 8, 2008. Accessed September 25, 2015.

From a Newspaper to Milk: The Borden Family Legacy in Texas

By Casey Schumacher, Texas Collection graduate assistant and museum studies graduate student

The Borden family collection at The Texas Collection has nothing to say about Lizzie Borden, the infamous Massachusetts ax-slinger. Believe me, I checked. However, in 1908, another notable Lizzie Borden, daughter of John P. Borden, wrote a brief history of her family’s deep Texan roots. Together, Lizzie’s father, her uncles, and her brothers helped create a family legacy that played a key role in establishing the Republic of Texas.

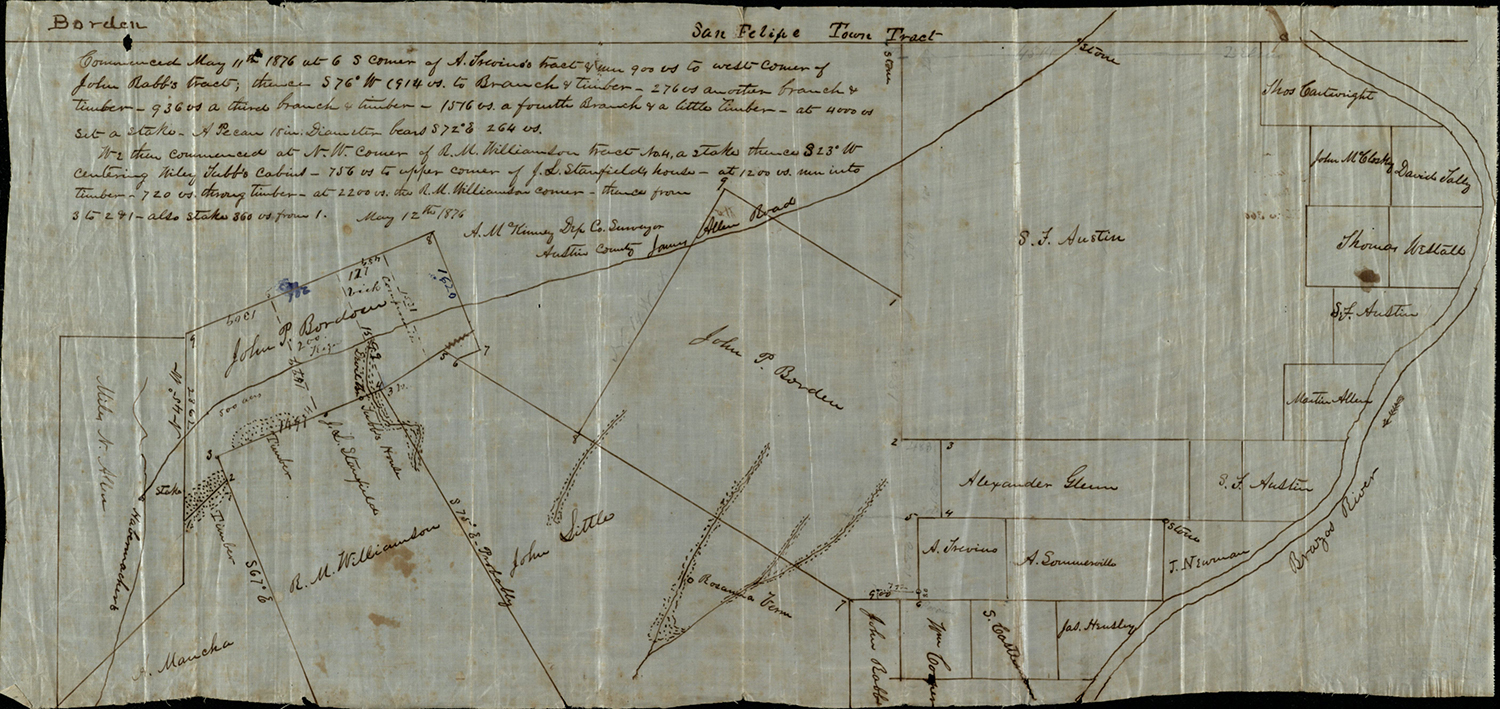

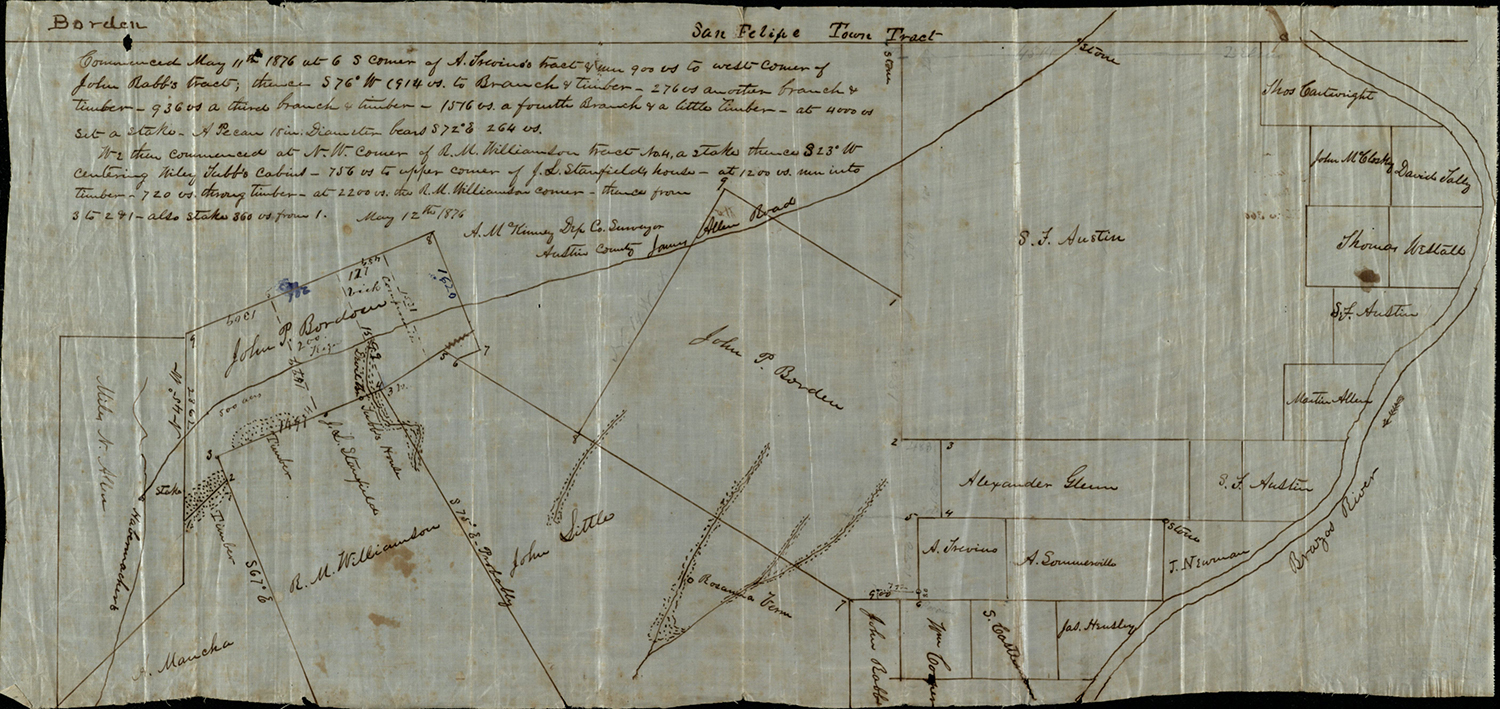

Gail Borden Sr. had four sons who were all very proud, upstanding Texans. The family owned extensive property in Austin and San Patricio County, some of which we can see in the land plots and deeds included in the collection. All four sons were landowners and prominent businessmen in south Texas, but their devotion to the Republic had a ripple effect across the state and into the ports of Galveston.

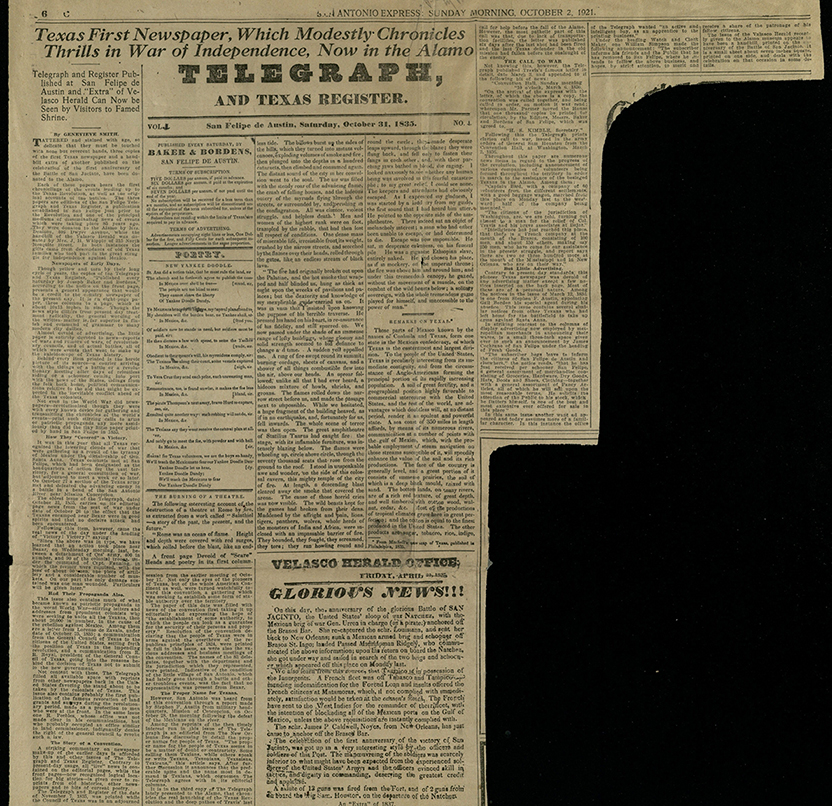

Gail Jr., the oldest of the four brothers, partnered with his closest brother Thomas and a family friend to establish Texas’ first newspaper, the Telegraph and Texas Register in San Felipe de Austin in 1835. Circulation increased rapidly and within a year, they had 700 subscribers. After encroaching Mexicans threw their press into Buffalo Bayou, Gail traveled to Cincinnati to purchase a new press. The next issue, dated August 2, 1836, included a reprint of the Constitution of the Republic of Texas. Even after the Borden brothers left the printing company, the newspaper continued to publish important documents that organized the Republic of Texas.

The Borden family didn’t just write about their Texas pride, however. In 1836, Gail Jr. presented Captain Moseley Baker with a flag he helped design for San Felipe. After leaving the newspaper, he went on to prepare the first topographical map of Texas. Soon after, he became the first collector of the port of Galveston and eventually founded the Borden Company.

At the same time Gail Jr. presented the flag at San Felipe, his younger brother John, Lizzie’s father, was a First Lieutenant under Captain Baker. John fought in the Battle of San Jacinto when he was 24 years old, and he was later appointed by Sam Houston as Commissioner of the General Land Office of Texas. Both of John’s sons would also leave home to fight for the Republic. The oldest son, Thaddeus, joined the Confederate Army at age 17 and was killed. John’s second son Sidney joined the Confederate Army at age 19 and eventually returned to establish the river port at Sharpsburg.

In her family history, Lizzie tells her nieces and nephews about each of her uncles and their dedication to the Republic of Texas. Naturally, she favors her father’s accomplishments and pays special homage to her brothers, Thaddeus and Sidney. She closes with a story of her and Sidney’s trip to the Philadelphia Centennial. Needless to say, the Bordens were a very close-knit and proud Texas family. The Borden family collection sheds some light on their influence in the Austin County and San Patricio County areas, as well as their dedication to the Republic of Texas.

Sources

Barbara Lane, “Sidney Gail Borden,” Find A Grave, Aug 6, 2006.

Joe B. Frantz, “Borden, Gail Jr.,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed December 16, 2014. Uploaded on June 12, 2010. Modified on October 28, 2013. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Leonard Kubiak, “San Felipe de Austin,” Fort Tumbleweed. 2007.

University of North Texas Libraries, “Telegraph and Texas Register,” The Portal to Texas History, December 14, 2014.

Research Ready: October 2014

Each month, we post a processing update to notify our readers about the latest collections that have finding aids online and are primed for research. Here are October’s finding aids:

- Frank O. Martin Independence papers, circa 1925 (#3927): Contains manuscript drafts and photographs for a newspaper article about Independence, Texas.

- BU Records: Staff Council, 1984-2008 (#BU/373): Constitutions, by-laws, minutes, and membership rolls about Baylor Staff Council events.

- Borden Family collection, 1839-1921 (#78): Includes land tracts, Confederate currency, and family papers.

- [Robinson] First Baptist Church records, 1866-1969 (#1434): Contains lists of members, minutes, and other church administrative materials.

Print Peeks: Kendall's Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition-A Firsthand Account of a Trip Gone Awry

By Sean Todd, Library Assistant

Texas has always attracted the adventurous, but few had the opportunity, combined with the skill, to write at any length about their experiences. That’s what makes George Wilkins Kendall’s 1844 Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition so special. As an experienced newsman, Kendall’s words bring to life an exciting narrative against the backdrop of the Republic of Texas.

Before Kendall came to Texas, he had already achieved success in the highly competitive newspaper business. After extensive travel throughout the United States as a young man and writing for newspapers in Boston and Washington, D.C., Kendall landed in New Orleans, where he co-founded the New Orleans Picayune in 1837. Kendall was not slowed by his success, and his interest began to turn to the Republic of Texas.

He learned that the President of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, was planning an expedition to Santa Fe in 1841. For years Santa Fe was a trading hub for all of western North America, making it a center of wealth. Lamar and many in Texas argued that Santa Fe was on the Texas side of the Rio Grande and therefore a part of Texas. The main goal of the Santa Fe Expedition was to open trade. However, if the military company found residents of Santa Fe wishing to be part of Texas, the expedition was to secure the region for the Republic.

Kendall jumped at the chance to join the expedition, first traveling to Texas, then leaving for Santa Fe with the large party in June 1841. After becoming lost, the expedition was soon captured in New Mexico by the Mexican Army. The prisoners were marched to Mexico City, and Kendall chronicles severe treatment during the journey southward. Following months of imprisonment and illness, Kendall secured his release in April 1842.

Upon his return to the United States, Kendall wrote about Texas and his experiences in Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, which became a popular book throughout the United States and Europe. After further adventures covering the Mexican-American War and the 1848 revolutions in Europe, Kendall returned to Texas. In 1856 he moved with his family to land he purchased near New Braunfels. He raised sheep and continued to write—achieving further successes in both fields. Kendall lived the rest of his life in Texas.

The popularity of Kendall’s Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition is both a testament to Kendall’s writing and to the growing interest in Texas in the 1840s. As the annexation of Texas to the United States became a major political topic and settlers continued to come to Texas, Kendall’s book was widely read. Demand for the text remained consistent through the decades after the first copy was printed in 1844. Other editions were printed in 1845, 1856, and well into the 20th century, with new editions coming out in 1929 and 1935. The 1844 editions found at The Texas Collection are small and worn, but remarkable artifacts that can directly connect any reader to the days of the Republic of Texas.

Bibliography:

Kendall, George Wilkins. Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition. New York: Harper Brothers, 1844.

Kendall, George Wilkins. Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition. Edited by Gerald D. Saxon and William B. Taylor. Dallas, TX: William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies, Southern Methodist University, 2004.

“Print Peeks” is a regular feature highlighting select items from our print collection.

Research Ready: November 2013

Each month, we post a processing update to notify our readers about the latest collections that have finding aids online and are primed for research. Here’s the scoop for November:

- [Waco] Columbus Avenue Baptist Church Records, Inclusive: 1903-2005, undated: Contains administrative documents, Sunday school study guides, sermon outlines, newsletters, and other printed material relating to Columbus Avenue’s church life.

- Gertrude Harris Cook papers, circa 1962: Correspondence and a manuscript Harris wrote on the Battle of Glorieta Pass, an important battle during the American Civil War in New Mexico.

- Frank Jasek Papers. Inclusive: 1915-2012, undated: Research files consisting mostly of notes, correspondence, photographs, compact discs, and literary productions used in the publication of Jasek’s book, Soldiers of the Wooden Cross: Military Memorials of Baylor University.

- Jones Texas Broadside Collection, Inclusive: 1822-1845: 127 folio broadsides from the Spanish, Mexican, and Republic periods of Texas history.

- [Dallas] Woodrow School of Expression and Physical Culture Scrapbooks, 1905-1929: Photographs, programs, school newspapers, and other materials from the Woodrow School, a girls’ finishing school in Dallas, Texas.

A Day in the (Texas Collection) Life: Benna Vaughan, Special Collections and Manuscripts Archivist

Meet Benna Vaughan, originally from Whitney, Texas, and Special Collections and Manuscripts Archivist, in our latest staff post giving you a peek into the day-to-day work of The Texas Collection:

In a nutshell, I get to work with some of the coolest stuff on campus. How often do you open a box and pull out a land grant signed by Stephen F. Austin? Or touch a set of pilot’s wings that were worn while flying in World War I? Or have someone call you up and say they found something you might like to have, such as an original 1894 Texas Cotton Palace medallion from the very first Texas Cotton Palace? Or handle a piece of Republic of Texas currency so thin you can see through it, and wonder where it has been and how many hands touched it and passed it on? I have a job where I can do this every day. I get to be in and amongst things that made history and that are now historical research materials. I am the Special Collections and Manuscripts Archivist at The Texas Collection, and it is my job to manage, preserve, and make available the wonderful special collections of Texana that come through our doors.

My days are varied. Most days I get to work with students and researchers alike on projects, from the smallest term paper to a full-sized book, commercial, or documentary. I might talk with donors who want to see their materials preserved, maintained, and used for research purposes. I attempt daily to process collections such as the Pat Neff collection, which took two years and the help of many graduate and undergraduate assistants to complete. I perform various inquiry tasks for researchers who contact me online, by phone, or in person. I sometimes give presentations to classes who will conduct research at The Texas Collection. In the fall, I also serve as an instructor for the University 1000 program for incoming freshmen students. I enjoy working with students as they begin their college careers and try to help them get adjusted to Baylor life. I guess you can say that for me everyday is a little different from the last.

Currently, I am beginning initial processing on the Roxy Grove papers. This includes research into her life and determining the condition of her records. (Are the pages brittle? How can we protect them? How are the records arranged?) I learned that Roxy Grove received two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s degree from Baylor. She began working at Baylor in 1926 and was the chair of the Music School for 17 years. Some of you may have classes in the building named after her: Roxy Grove Hall (third photo from top on the linked page). With every collection, I learn about the personal side of the individuals or organizations as I research and process their collections. For me, working on another person’s materials makes a connection with that person and allows you to discover the person, organization, or even place, through the things that are left behind.

But it is not always idyllic. Sometimes a collection will come in that was stored in a barn or a garage and the boxes contain bugs, and the records are in poor condition. When that happens, I get to be an exterminator. I pitch in to help with special projects and the administrative tasks that come with a special collections library. No matter what I’m doing, it is a great job, at a great place, and I am blessed to be here.

The Texas Collection turns 90 this year! But even though we’ve been at Baylor for so long, we realize people aren’t quite sure what goes on in a special collections library and archives. So over the course of 2013, we are featuring staff posts about our work at The Texas Collection. See other posts in the series here.