Each month, we post a processing update to notify our readers about the latest collections that have finding aids online and are primed for research. Here’s the scoop for April:

- Sadie C. Cannon papers, undated: An unpublished manuscript, Sing Hallelujah, describing the author’s life in the American South during the 1880s.

- Chapman-McCutchan papers, 1845-1903: Financial documents, legal documents, and literary materials relating to early Texans William S. Chapman and William H. McCutchan.

- Richard L. Farr papers, 1858-1889: Correspondence between Richard L. Farr and his wife Elizabeth K., as well as between other Farr family members and friends. Most of the correspondence dates from Richard’s service in the 30th

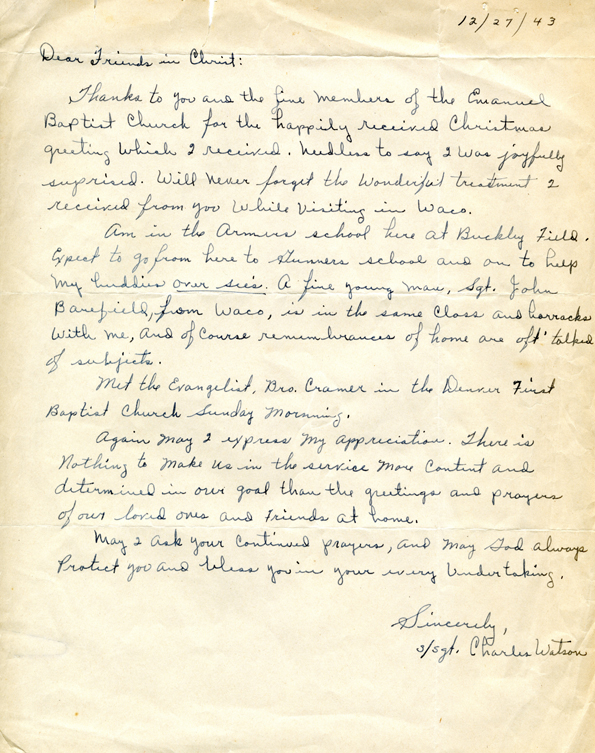

Georgia Infantry during the American Civil War. - Elsie and Tilson F. Maynard papers, 1942-1983: Primarily letters from former members of the Emmanuel Baptist Church of Waco who were serving in the armed forces during World War II. Addressed to Reverend and Mrs. Maynard and other church members, many of the letters express their writers’ gratitude for the church’s concerns and prayers.

- [Waco] Memorial Baptist Church collection, 1943-2003: Materials compiled by Waco’s Memorial Baptist church concerning the church’s financial, legal and historical records, from the inception of the church to its closing.

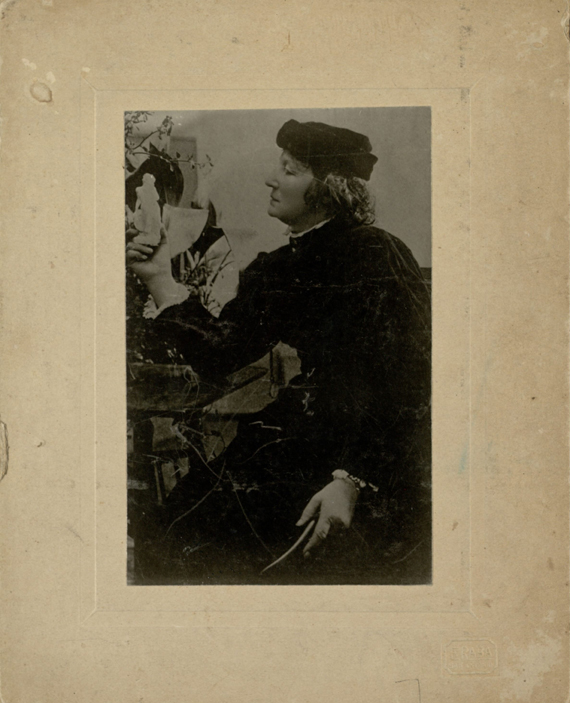

- Ney-Montgomery papers, 1836-1913: The Ney-Montgomery materials consist of literary materials, manuscripts, correspondence, legal documents, and photographic materials relating to artist Elisabet Ney and her husband, Edmund Montgomery.

- Gordon Kidd Teal papers, 1919-1990: School materials, personal materials, professional materials, and awards accumulated by Dr. Gordon Kidd Teal, a famous twentieth century scientist who graduated from Baylor University in 1927. Teal invented the first commercial silicon transistor for Texas Instruments, among other achievements.