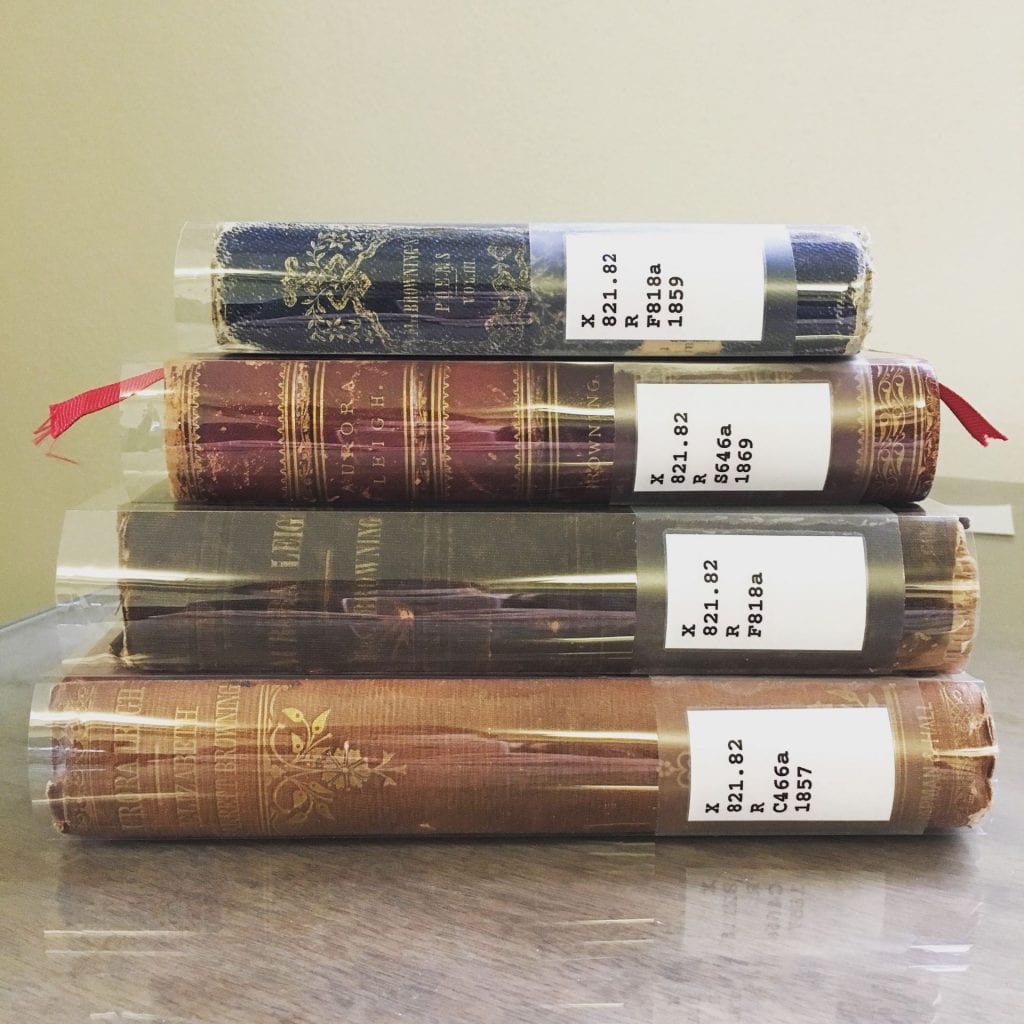

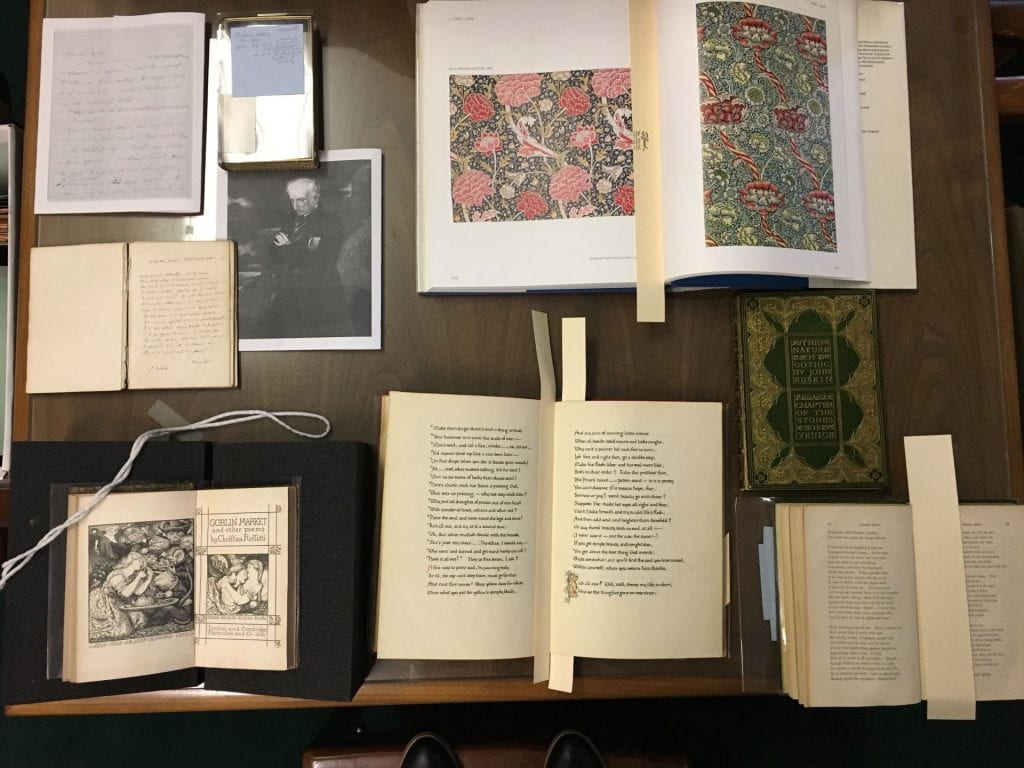

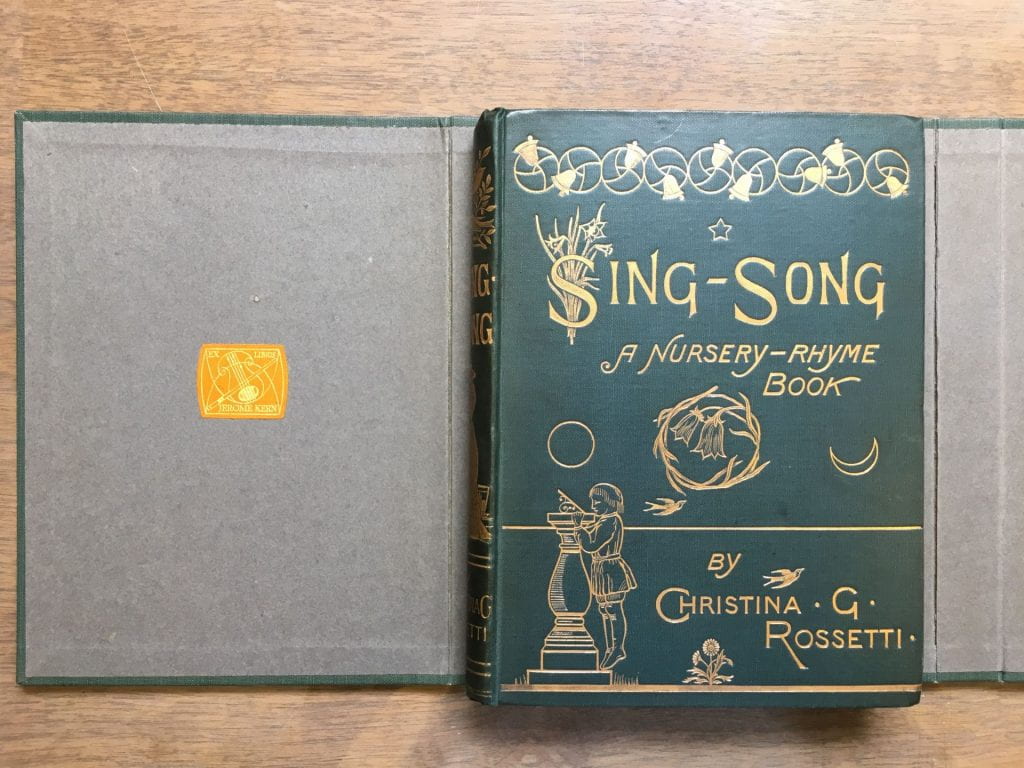

On December 9th at 9:05am, Dr. Kristin Pond’s English 3351: Literary Networks in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Centuries course will be presenting their Great Exhibition. This is a class project which requires students to explore what artifacts, including original letters, manuscripts and books, photographs, and actual objects exist at the Armstrong Browning Library related to each student’s assigned author.

The exhibition will be on display in the Hankamer Treasure Room for the entire morning December 9th, 2019.

To prepare for the exhibition, students wrote a short biography of their author and practiced analyzing an artifact for what it reveals about their author. A sample of one student’s preliminary research follows.

Mary Shelley – Life, Writings, and Browning Correspondence

Mary Shelley, daughter of political radical William Godwin and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (writer of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman), was born in 1797. Sadly, her mother died due to an internal bacterial infection following childbirth. Possibly to escape a troubled household and a horrible stepmother, 16-year-old Mary eloped in 1814 with the then-married romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Through her husband Percy, Mary Shelley continued to receive encouragement on her writing, as she had for most of her life under the watch of her intellectual father. On the point of Percy’s influence, however, there have been a number of misunderstandings – all at the expense of Mary Shelley’s creative reputation.

In her biography Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters, author Anne Mellor analyzes Mary Shelley’s writings and journals through a feminist lens, validating Mary’s standing as an independent writer of Frankenstein, a gothic masterpiece. Contrary to what some may believe, Percy was an avid supporter – not a controlling editor – of his wife’s writings.

Prior to the 21st century, scholars had assumed that Percy had essentially taught his wife how to write well. This assumption may be based on the fact that one of Mary’s copies of Frankenstein contains several grammatical and syntax edits by Percy. In one edition of Frankenstein, Percy actually wrote the novel’s preface as if he was Mary. Moreover, Mary’s writing contains a description of Mont Blanc which some have linked with Percy’s “Mont Blanc” poem. To make matters worse, due to the constraints of the time, the first copies of Frankenstein were actually published under Percy Shelley’s name.

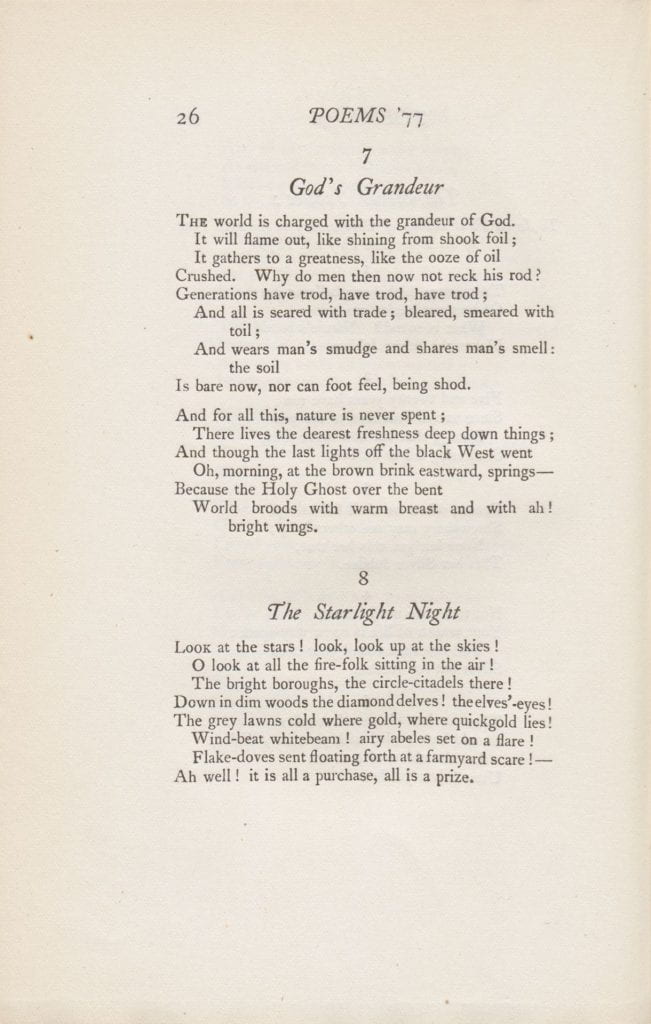

That being said, however, Mary Shelley did craft the vast majority of Frankenstein, not to mention her other works. Being as independent and nonconformist as her feminist mother, Mary most likely would not have permitted over-involved literary edits on Percy’s part. In her History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, when describing the natural world about her, Mary says, “God has not reduced our dwelling-place – as Puritans would his – to a bare meeting-house, all there is radiant in glorious colours” (12). Through her criticism of Puritan religion and her gushing over natural beauty, Mary not only reveals her open-minded, non-conformist attitude towards history and society but also her idealistic writer’s heart.

A romantic spirit, Mary found her soulmate and escape from the world in Percy Shelley, who viewed her as his intellectual equal. For the eight years they lived together, Percy Shelley was deeply in love with Mary, to the point that he sometimes expressed wishes to retreat onto an island with her and his child, them against the world. Evidence of a mutually constructive literary relationship can be found in their correspondence. For example, in a letter by Mary Shelley to a friend, Percy interposes, writing “Poor Mary’s book has come back with a refusal which has put me in rather ill spirits.” In another letter, Percy writes to Mary, “Be severe in your corrections, & expect severity from me, your sincere admirer. – I flatter myself you have composed something unequalled in its kind.” Rather than lead Mary’s writing endeavors, Percy avidly supported them, offering constructive criticisms. His prefaces to Mary’s Frankenstein and History of a Six Weeks’ Tour were part of a collaborative effort, not of a failing on Mary’s part. In turn, Mary offered up her own support and criticisms of Percy’s writing, including his poems “The Witch of Atlas” and “Rosalind and Helen,” which Percy might not have published if not for her encouragement. Following Percy’s tragic drowning in 1822, Mary edited and published Percy’s works posthumously.

Through Frankenstein and Mary Shelley’s account of Frankenstein’s creation, Mary Shelley reveals herself to be curious, conscientious, and sensitive, channeling her life’s questions, worries, and griefs into her writing. In 1816, Mary Shelley received an awaited opportunity to prove her worth as a writer when Lord Byron suggested to his Shelley friends that they each write a ghost story. Having been the only one of her peers to take Byron’s story prompt seriously, Mary Shelley was finally inspired after a period of much creative anxiety. Drawing from her recent grief and nightmares about childbirth, Mary Shelley “gave birth” to a “hideous progeny,” in the form of Victor Frankenstein’s monster. In 1817, at the age of nineteen, Mary Shelley published Frankenstein following the suicide of Percy Shelley’s wife Harriet, the suicide of Mary Shelley’s half-sister Fanny, and the death of Mary Shelley’s infant daughter. Undoubtedly, these deaths influenced the macabre tone and themes of the novel.

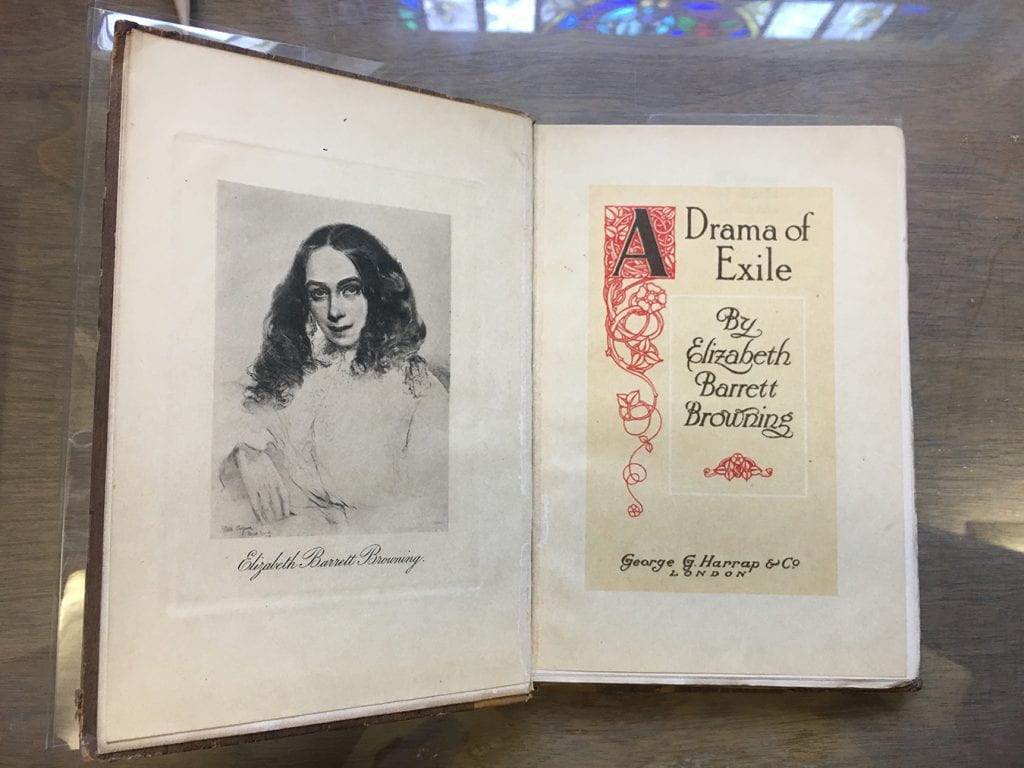

Like Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Mary Shelley was a key component of a 19th century network of feminist writers. Just as Elizabeth Browning wrote poems in honor or in critique of other female writers, such as her “Stanzas Addressed to Miss Landon,” Mary Shelley likely looked up to a network of precursing female gothic writers as literary models. These writers included Ann Radcliffe (writer of The Mysteries of Udolpho) and Charlotte Dacre (writer of The Confessions of the Nun of St. Omer).

Yet, in spite of their female literary backgrounds, very little communication existed between Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Mary Shelley. Despite her success as an author, it appears that Mary Shelley was overshadowed by Percy Shelley in the Brownings’ eyes. While Percy Shelley’s writings and beliefs heavily influenced Robert Browning (he became an atheist vegetarian after reading Percy’s Queen Mab), Browning’s only mention of Mary Shelley in his letters was of her sorry state following Percy Shelley’s death. An 1845 letter to Elizabeth Barrett Browning is the only published letter in which Robert Browning writes of her. In this letter, Browning recalls:

The ‘Mary dear’ with the brown eyes, and Godwin’s daughter and Shelley’s wife, and who surely was something better once upon a time…when she and the like of her are put in a new place, with new flowers, new stones, faces…[she] wisely saying ‘ who shall describe that sight ! ‘ — Not you, we very well see…

Robert Browning then goes on to say:

But once she travelled the country with Shelley on arm; now she plods it, Rogers in hand…but she is wrong every where, that is, not right, not seeing what is to see, speaking what one expects to hear — I quarrel with her, for ever, I think.

In spite of Mary Shelley’s success as a writer, Robert Browning saw her as a sort of soft-eyed sweetheart, consumed by grief to the point that she was annoying to be around. Rather than refer to her as “author of Frankenstein” or something more flattering, Browning identifies Mary Shelley by her radical writer relations. Briefly, he does recognize Mary Shelley’s past accomplishments when he says, “something better once upon a time.” Otherwise, he is annoyed by her apparent inability to say or write anything interesting or insightful.

This characterization of Mary Shelley is surprisingly harsh, considering that the Brownings may have respected Mary Shelley’s works. In fact, at least two of the books in their library were ones that Mary Shelley had either written or edited: History of a Six Weeks’ Tour Through a Part of France, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland, and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Posthumous Poems. That being said, they did not own a copy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which may explain their misperception of grieving gothic Mary as overly sweet or passive. If only the Brownings knew that Mary had saved the heart of Percy, a small organ wrapped in a sheet of posthumous poetry and tucked away inside her desk drawer.

Works Cited

Browning, Robert, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Barrett. Vol. 1, New York and London, Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1899. 2 vols.

Creech, Melinda. “Giving Nineteenth Century Women Writers a Voice and a Face — Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley [née Godwin] (1797–1851).” Armstrong Browning Library and Museum, Baylor University, 23 July 2013, blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/tag/frankenstein/. Accessed 23 Sept. 2019.

Mellor, Anne K. Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. New York and London, Routledge, 2009.

Mercer, Anna. “The Literary Collaboration of Mary and Percy Shelley.” Dove Cottage and the Wordsworth Museum, Wordsworth Trust, 2017, wordsworth.org.uk/blog/2015/02/15/mine-own-hearts-home-the-literary-collaboration-of-mary-and-percy-bysshe-shelley/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.

Poetry Foundation, editor. “Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.” Poetry Foundation, edited by Poetry Foundation, 2019, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/mary-wollstonecraft-shelley. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.

Pottle, Frederick A., M.A. Shelley and Browning: A Myth and Some Facts. Pembroke Press, 1923.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. History of a Six Weeks’ Tour. London, T. Hookam, 1817.

Shelley, Percy. Letter to Mary Shelley. 10 Aug. 1821. Letters. Edited by Frederick L. Jones, vol. 324. Oxford University, 2015.

Shelley, Percy. Letter to Mary Shelley. 15 Aug. 1821. Letters. Edited by Frederick L. Jones, vol. 339. Oxford University, 2015.

Theisen, Colleen. “Mary and Percy Shelley Letter Mentions Frankenstein Rejections.” The University of Iowa Libraries, U. of Iowa, 8 Oct. 2012, blog.lib.uiowa.edu/speccoll/2012/10/08/special-collections-mary-and-percy-shelley-letter-mentions-frankenstein-rejections/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2019.