I have, as I said before, learned the English law piecemeal, by suffering under it. My husband is a lawyer, and he has taught it me, by exercising over my tormented and restless life every quirk and quibble of its tyranny; of its acknowledged tyranny; acknowledged, I say, not by wailing, angry, despairing women, but by Chancellors, ex-Chancellors, legal reformers and members of both Houses of Parliament.

Caroline Norton. From A Letter to the Queen on Lord Chancellor Cranworth’s Marriage and Divorce Bill. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1855.

Dr. Kieran Dolin, professor of English and Cultural Studies at the University of Western Australia, has written several articles on Caroline Norton. He is particularly interested in Caroline Norton’s writings and her activism to reform the law relating to women in Victorian England. He suggested the quotation above.

Born on March 22, 1808, the third child of seven, Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Sheridan seemed destined to become an established writer. Her mother was a novelist and her grandfather was a famous playwright, Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Not surprisingly, the young Caroline expressed a knack for literature. At age thirteen, she had already written her first booklet, The Dandies Rout. At Shalford boarding school in Surrey, George Norton noticed the beautiful Caroline, which resulted in their marriage in 1827.

Caroline and George Norton seemed an almost perfect couple. Caroline was beautiful and smart and George Norton was the brother of her friend, also a barrister, and a Member of Parliament. However, her personal life soon became riddled with strife. To Caroline’s surprise, Norton turned out to be a drunk with a violent temper, and he often mismanaged money. In English Laws for Women in the Nineteenth Century (1854), Caroline Sheridan Norton gives accounts of being beaten as early as two weeks into their marriage. She writes about harsh experiences, such as having a hot tea-kettle purposely set on her hand. Through it all, she was still able to publish her first poetic work titled The Sorrows of Rosalie: A Tale with Other Poems in 1829. This work was well received by the public. Despite the troubles, the marriage produced three sons named Fletcher, Brinsley, and William. Caroline was even beaten weeks before she gave birth to her third son William.

English law made it extremely hard to get a divorce, especially since Caroline had endured such harsh treatment for so long. After she was accused of having an affair with the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, George Norton became even more vicious. He took both Melbourne and Caroline to court, but both were found innocent of adultery. Although Caroline Norton was found innocent, she could not divorce George Norton, and the abuse continued. Norton took away Caroline’s children, and the fight began. Advocating for women’s rights became Caroline Norton’s primary concern. She wrote a pamphlet titled “The Separation of Mother and Child,” which promoted The Infant Custody Act of 1839. The more Caroline campaigned, the more she was able to get accomplished. Caroline Norton is well-known for writing A Letter to the Queen which advocated for the rights of married women in 1855. She also helped to pass acts such as the 1857 Matrimonial Act and the Married Woman’s Property Act (1870). Caroline eventually got custody of her two living children after they were twenty-one. Her success as an activist eventually led to her ability to divorce George Norton, but she did not remarry until after his death. At the advanced age of sixty-nine, Caroline Sheridan married a Scottish politician named William Maxwell Stirling. She only enjoyed three months of a blissful marriage before she died in 1877.

Caroline Norton. “The Invalid” in The Keepsake. London: Hurst, Chance, and Company, 1840.

Caroline Norton’s short story, “The Invalid,” published in the 1840 edition of The Keepsake, displayed above, tells the story of a young lady, Mariana, who is on her deathbed when her sister, Tersa, comes to visit. The story not only highlights education for women, but Norton also exposes the tragedy that can befall a woman who is wrongly in love. Educated by her uncle, Mariana learns to “lay a bridge stone by stone” between her mind and that of her learned uncle. Norton further makes the claim that the best “education comes through free intercourse with superior and cultivated companions.” This focus on the education of women provides a major theme in the short story. Though Count Arnstein, a man who comes to live with Mariana and her uncle, dislikes her intellect at first, he quickly begins to love her for it. Consequently, Norton builds her case for a prominent role of women in politics through the character and competence of Mariana. In addition, a major theme of the short story is that of improper love. Mariana falls in love with Count Arnstein, and he reciprocates. However, after he tells her that he is married and begs her to accompany him to visit his wife, she is heartbroken and becomes very ill. She later recalls to Tersa just before her death, “It is that I have seen at one dreadful glance the shattering of earth’s best illusion.” Ultimately, Mariana dies alone and forgotten. Norton’s portrayal of Mariana’s demise is a strong social commentary on the lack of options for a woman without a husband or any prospects. The story she writes echoes much of her own experience.

The Armstrong Browning Library has seven nineteenth-century books authored by Caroline Norton, including this unusual copy of The Sorrows of Rosalie.

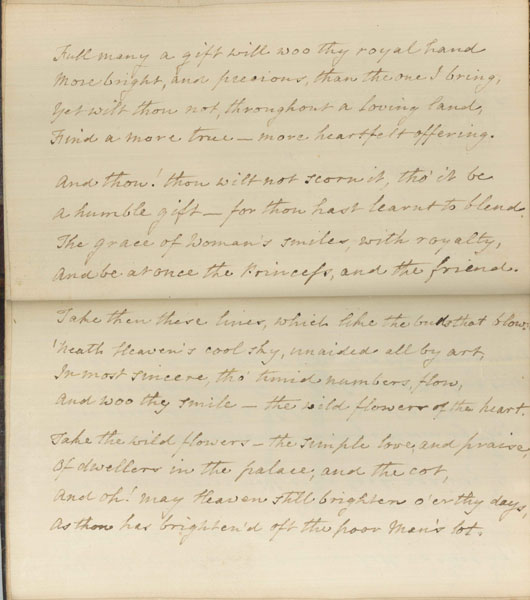

Caroline Norton. “A Royal Christmas Gift to the Duchess of Clarence, Christmas 1828.” Autograph Manuscript, in The Sorrows of Rosalie: A Tale with Other Poems. London: J. Ebers, 1828.

This volume, with Norton’s poem inscribed on the front leaves, was presented to the Duchess of Clarence by August Fitz-Clarence, the illegitimate son of her husband, the Duke of Clarence. In June of the following year the Duke succeeded to the throne of England as William IV and the Duchess became Queen Adelaide.

Nancy Gross

Bianca Arechiga

Mary Philippus