By Amanda Vernon, Ph.D.

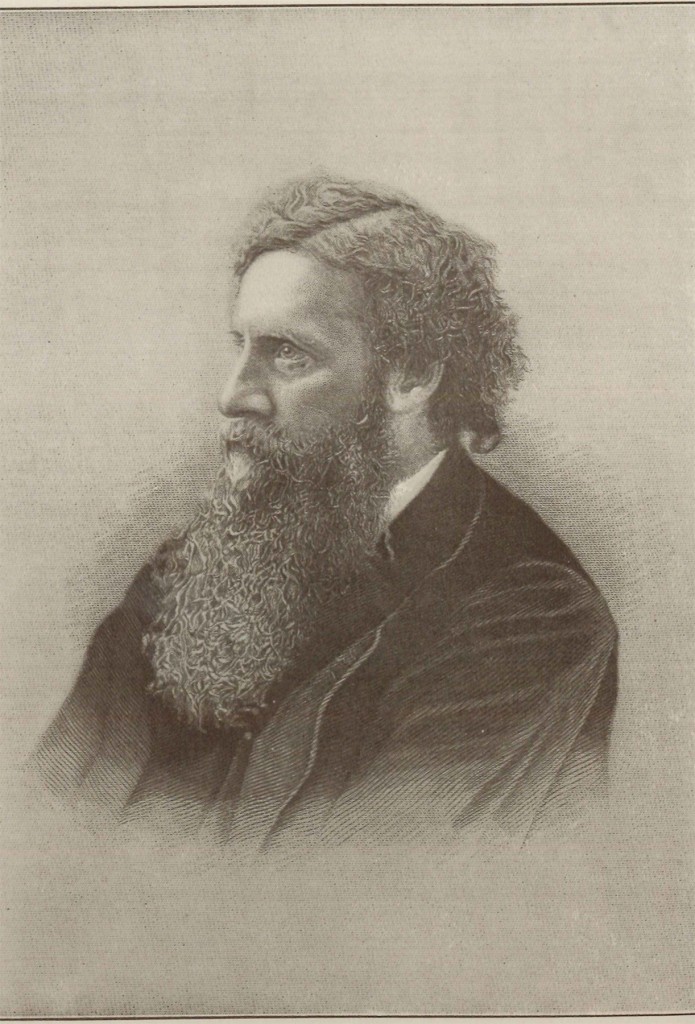

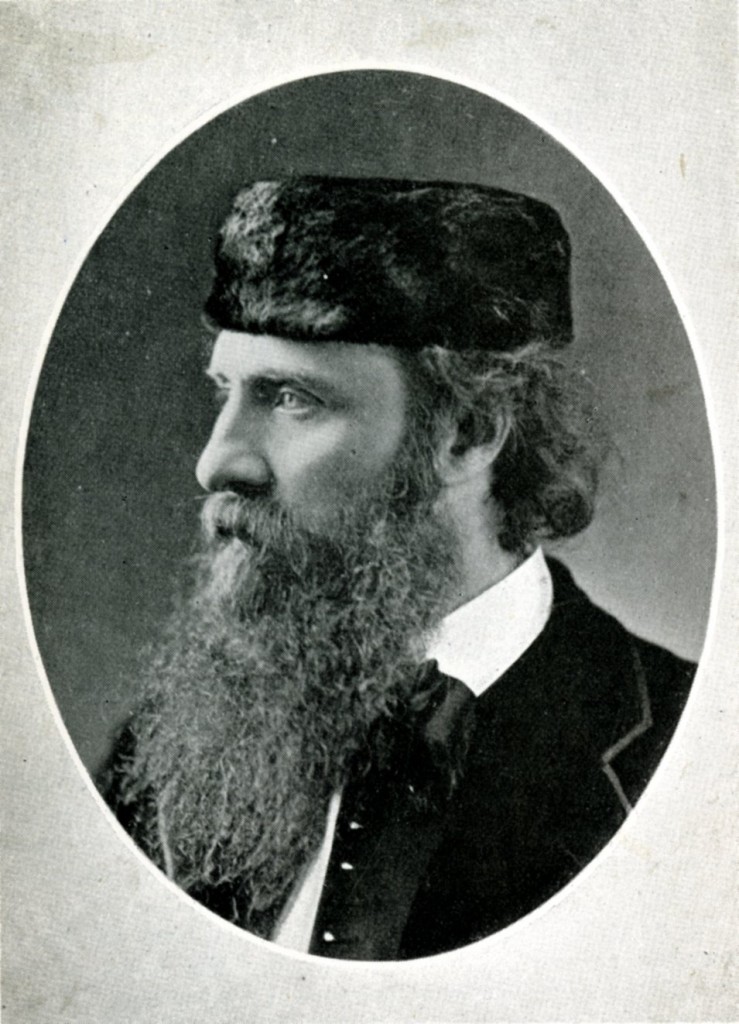

I spent a wonderful month of March at the Armstrong Browning Library, where I had the privilege of working on materials related to Elizabeth Barrett Browning and George MacDonald. My current research project considers Victorian ideas of curative or therapeutic reading and the links between these ideas and traditions of spiritual practice.

For me, there is a genuine thrill in having the opportunity to handle objects either created or owned by someone who I have spent a lot of time ‘getting to know’. When I handle old letters or books, I often feel like I’ve found a sort of wormhole—a connection with a physical past I’ve only accessed through my imagination. Engaging with material objects offers a fresh awareness of the lived experience of a writer whose ideas I am familiar with, but whose life as a person—existing in all of the physical realities of the everyday—sometimes fades into the background. I have sometimes found that, as I am looking at the pencil markings in a book or touching a dried flower enclosed in a letter, the person comes alive in a new way.

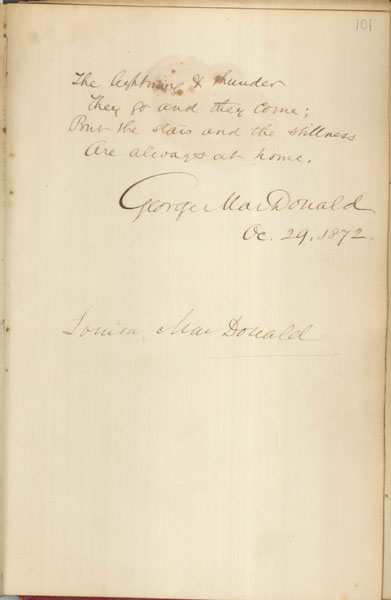

One of the aims of my visit to the ABL was to look at MacDonald’s books. I undertook my PhD research on MacDonald in his capacity as a literary scholar, and was keen to see what the annotations in his copy of Robert Browning’s Christmas Eve and Easter Day might have to reveal about MacDonald’s earliest published work of literary criticism: an 1853 review of ‘Christmas Eve’ in The Monthly Christian Spectator. I was especially curious to know whether the annotations reflected his writings on reading practice and the links between reading and spiritual practice. Alongside my interest in MacDonald, I also planned to look at EBB’s letters and the books in her personal library, in the hopes of discovering what they reveal about how she read. The library catalogue detailed some annotations in her books—would these indicate anything about how she used books when she was bed-bound? Would her letters show whether she saw reading as a source of comfort or consolation?

George MacDonald’s copy of Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day: A Poem by Robert Browning. London, Chapman & Hall, 1850. ABL Rare X 821.83 P5 C466c c. 13

I was particularly struck by the marginalia in EBB’s copy of the six volumes of ‘Wordsworth’s Poetical Works’. Some of these notes consist simply of crosses or lines under or next to words. Others, however, demonstrate her critical engagement with the text in a more explicit way. EBB questions why certain metaphors are employed and also crosses out words and replaces them with others (words which, presumably, she thinks work better). The notes reveal EBB’s thoughtfulness as a scholarly reader and poet—an individual who is engaged with analysing the poetic and linguistic choices Wordsworth makes in both his poems and his prose (Volume 1 includes his preface to the 1815 Poems and dedication to Robert Jones). Going by her marginalia, EBB’s reading seems to have been primarily focused on the craft of writing and the process of creativity.

While relevant to analysing EBB’s reading practices in general, I wasn’t sure whether my observations had any relevance to my project’s interest in consolatory reading. After mulling it over for a while, and discussing it over lunch with the generous and brilliant Prof. Joshua King, I began to wonder if my definition for what counts as consolation might be too narrow. I for one have certainly found solace in focused intellectual engagement and I know that concentrated attention can be therapeutic, whether the attention is on poetry or a pattern of breathing (which are, of course, also related to one another). While I’m still mulling the question over, the challenge EBB’s marginalia offered to my understanding of the kinds of texts that might be considered ‘therapeutic’ or ‘consolatory’ has been helpful as I continue to develop my project.

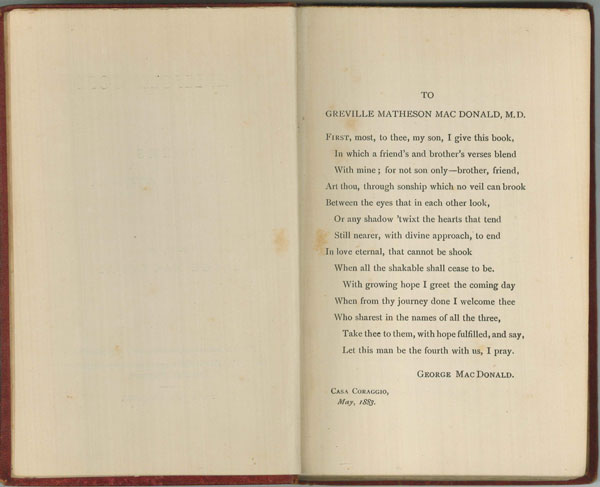

Considering EBB’s reading in light of the idea of consolation connects to another book I discovered in the ABL: Hymns and poems for the sick and suffering, edited by Thomas Vincent Fosbery. The ABL has an eighth edition copy, published in 1871 and carrying an inscription on the title page to Robert Browning ‘with kind regards and many thanks’ from the editor. The volume contains several poems by EBB (which were also included in earlier editions): ‘Comfort’, ‘Bereavement’, ‘Reparation’, ‘Consolation’, and The Sleep’. As indicated by the book’s title, the collection frames these and other poems as a means of emotional and spiritual consolation for readers. The book, which is dedicated ‘to the Sick and Suffering’, aims to soothe and brighten their ‘helpless days and wearisome nights’. The numerous editions of the book indicate its popularity in the nineteenth century and gesture towards the importance of the idea of consolatory reading in the period.

Robert Browning’s copy of Hymns and Poems for the Sick and Suffering edited by Thomas Vincent Fosbery. London: Rivingtons, 1871. ABL Brownings’ Library X BL 245.21 F746h 1871

In addition to the treasures I was able to examine during my time at the ABL, I spent happy hours reading in the Moody and Jones Libraries and enjoying coffee and lunches with members of Baylor’s English faculty. It was an unexpected delight to be able to attend some of the annual Beall Poetry Festival, including a captivating talk by the poet Christian Wiman. The hospitality and expertise of the ABL librarians, curators, and other staff made my stay pleasant and productive. I was particularly touched when, on my final morning, Christi Klempnauer brought in two types of local doughnuts for me to try before I flew back to Germany! I am grateful to have spent my month as a Visiting Scholar in such a warm and intellectually-stimulating community and hope this will be the first of many visits.

![Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Manuscript of A Drama of Exile. Page 25. [D0216]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-2-v0mlin-225x300.jpg)

![Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Detail of Marginalia in Xenophon’s Memorabilia. Page 181. [ABLibrary Brownings’ Library XBL 888.3x55m]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-3-10qn32q-225x300.jpg)

![George MacDonald. Marginalia in Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day: A Poem, by Robert Browning. London: Chapman and Hall, 1850. Page 15. [ABLibrary Rare X821.83 P5 C466c c.13]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-4-1wekpt0-225x300.jpg)

![Robert Browning. Marginalia in Sartor Resartus, by Thomas Carlyle. Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1837. Page 72. [ABLibrary Brownings’ Library X BL 824.8 C286s 1837]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-5-1zhpfd5-225x300.jpg)

![Letter from George MacDonald to Sally [last name unknown]. 13 September 1882.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2014/12/1882-September-13-1-2hetgdc-674x1024.jpg)

![Letter from George MacDonald to Sally [last name unknown]. 13 September 1882.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2014/12/1882-September-13-2-1ynchnu-661x1024.jpg)

![Letter from George MacDonald to Sally [last name unknown]. 13 September 1882.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2014/12/1882-September-13-3-1thax31-675x1024.jpg)

![Letter from George MacDonald to Sally [last name unknown]. 13 September 1882.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2014/12/1882-September-13-4-xtcgef-673x1024.jpg)

![Letter from George MacDonald to [Mr.] Hutchinson. 1 January 1890.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2014/12/1890-January-1-1rr1sd4-1024x822.jpg)

![Letter from George MacDonald to Mr. Erskine. Monday, [no date].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2014/12/Monday-1mv633q-647x1024.jpg)

![Letter from George MacDonald to an Unknown Correspondent. 6 February [no year].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2014/12/ny-February-6-1x8iglu-665x1024.jpg)