Coloring enthusiasts get ready! The Armstrong Browning Library and more than 30 other special collections libraries and cultural heritage institutions are inviting you to #ColorOurCollections, an event organized by the New York Academy of Medicine Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health. From February 1-5, 2016, download images from the Armstrong Browning Library’s collection, color them, and share them on social media using the hashtag #ColorOurCollections.

To download an image, click on the image below and then print or click on the image, right click, and “save image as” before printing. To download the coloring book version of the image, click on the link provided.

Special thanks to Eric Ames, curator of digital collections for the Baylor Libraries, for creating the coloring book pages for us!

Happy coloring!

The Grave, a Poem by Robert Blair. Illustrated by Twelve Etchings Executed from Original Designs [by William Blake]. London: Printed by T. Bensley, for the proprietor, R.H. Cromek, and sold by Cadell and Davies, [etc.], 1808. [ABLibrary Rare OVZ X 821.59 B635g]

The Grave, a Poem by Robert Blair. Illustrated by Twelve Etchings Executed from Original Designs [by William Blake]. London: Printed by T. Bensley, for the proprietor, R.H. Cromek, and sold by Cadell and Davies, [etc.], 1808. [ABLibrary Rare OVZ X 821.59 B635g]

Coloring book version: Blake Coloring Page

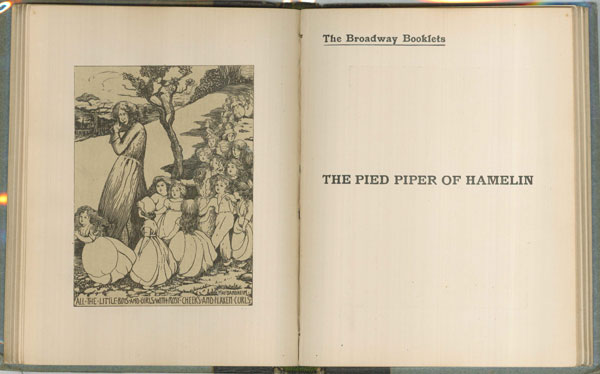

The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Robert Browning. Illustrated by Jane E. Cook. London: Printed for Private Circulation, 1880. [ABLibrary Rare OVZ X 821.83 O1 C771p c.2]

The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Robert Browning. Illustrated by Jane E. Cook. London: Printed for Private Circulation, 1880. [ABLibrary Rare OVZ X 821.83 O1 C771p c.2]

Coloring book version: Browning Coloring Page

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J4]

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J4]

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J4]

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J4]

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J23.1]

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J23.1]

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J23.1]

Sketch by Robert Browning, Sr., father of poet Robert Browning. [Browning Collections J23.1]

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. Ornamented with pictures designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and engraved on wood by W. H. Hooper. Upper Mall, Hammersmith, Middlesex: Kelmscott Press, 1896. [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ PR1850 1896]

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. Ornamented with pictures designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and engraved on wood by W. H. Hooper. Upper Mall, Hammersmith, Middlesex: Kelmscott Press, 1896. [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ PR1850 1896]

Coloring book version: Chaucer Coloring Page

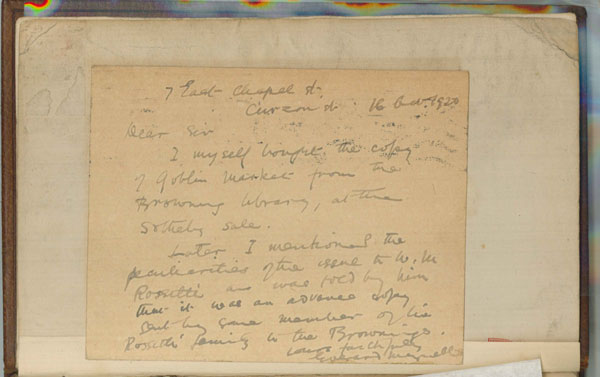

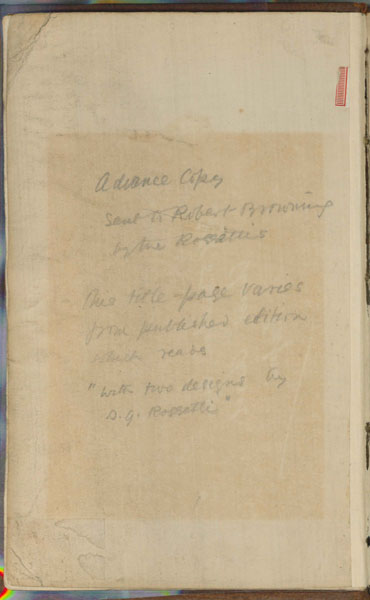

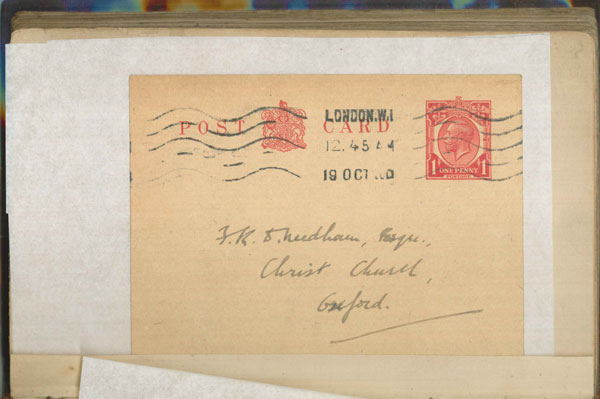

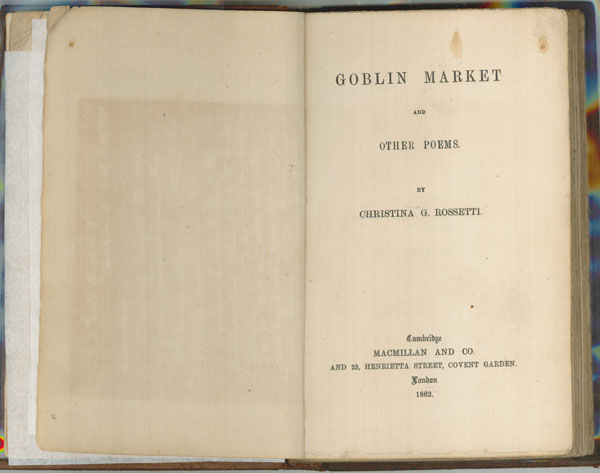

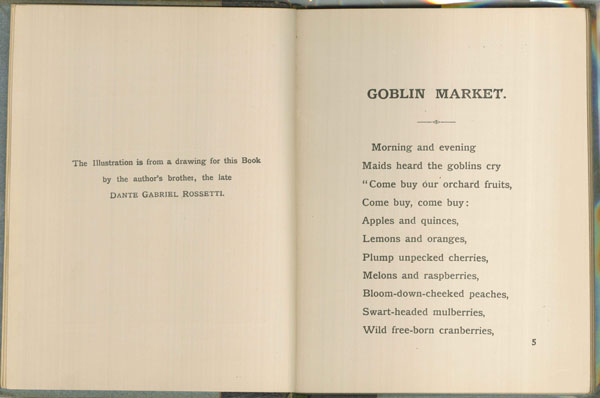

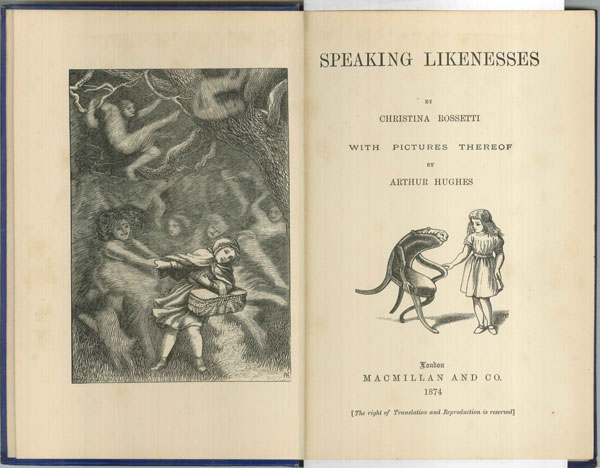

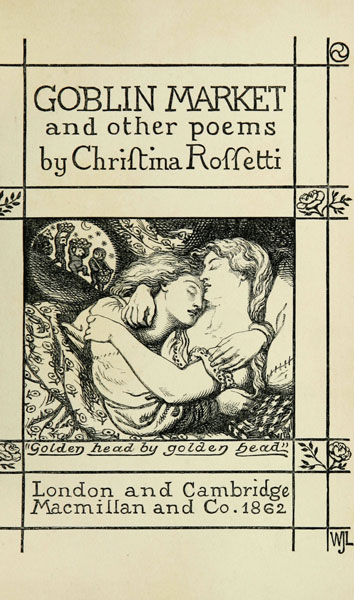

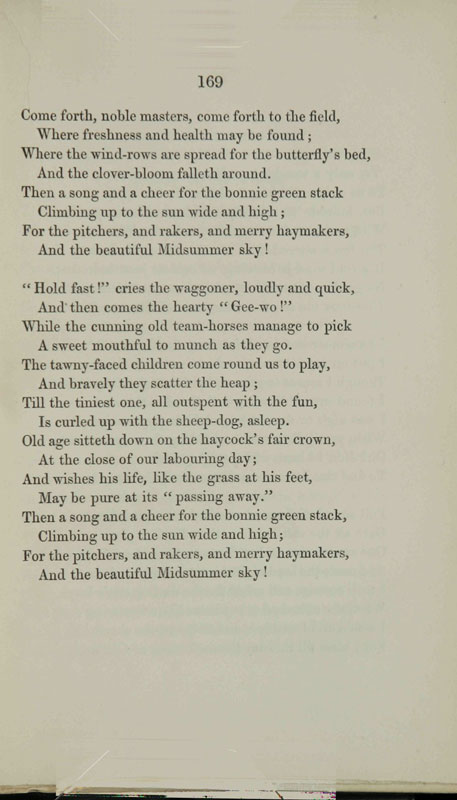

Goblin Market and Other Poems by Christina Rossetti, with two designs by D. G. Rossetti. Cambridge, London: Macmillan and Co., 1862. [ABLibrary 19thCent PR5237 .G6 1862 and online]

Goblin Market and Other Poems by Christina Rossetti, with two designs by D. G. Rossetti. Cambridge, London: Macmillan and Co., 1862. [ABLibrary 19thCent PR5237 .G6 1862 and online]

Coloring book version: Rossetti Coloring Page

Aratra Pentelici. Six Lectures on the Elements of Sculpture, Given before the University of Oxford in Michaelmas Term, 1870 by John Ruskin. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1891. [ABLibrary 19thCent ND467 .R93 1891]

Aratra Pentelici. Six Lectures on the Elements of Sculpture, Given before the University of Oxford in Michaelmas Term, 1870 by John Ruskin. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1891. [ABLibrary 19thCent ND467 .R93 1891]

Coloring book version: Ruskin Coloring Page

The Works of Mr. William Shakespear. London: Printed for Jacob Tonson, 1709. [ABL Stokes Shakespeare 822.33 S527w 1709 v.1]

The Works of Mr. William Shakespear. London: Printed for Jacob Tonson, 1709. [ABL Stokes Shakespeare 822.33 S527w 1709 v.1]

Coloring book version: Shakespeare Coloring Page