courtesy of Bettina Lehmbeck

courtesy of Bettina Lehmbeck

I believe we are touching on better days, when women will have a genuine, normal life of their own to lead. There, perhaps, will not be so many marriages, and women will be taught not to feel their destiny manque if they remain single. They will be able to be friends and companions in a way they cannot be now. All the strength of their feelings and thoughts will not run into love; they will be able to associate with men, and make friends of them, without being reduced by their position to see them as lovers or husbands. Instead of having appearances to attend to, they will be allowed to have their virtues, in any measure which it may please God to send, without being diluted down to the tepid ‘rectified spirit’ of ‘feminine grace’ and ‘womanly timidity’-in short, they will make themselves women, as men are allowed to make themselves men.

Geraldine Jewsbury to Jane Welsh Carlyle, [1849]

from Selections from the Letters of

Geraldine Endsor Jewsbury to Jane Welsh Carlyle,

by Mrs Alexander [Annie] Ireland,

London and New York: Longmans, Green 1892, p. 347.

The above quotation was suggested by Aileen Christianson, senior lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, who has worked as a researcher and editor on the Duke-Edinburgh edition of The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle since 1967.

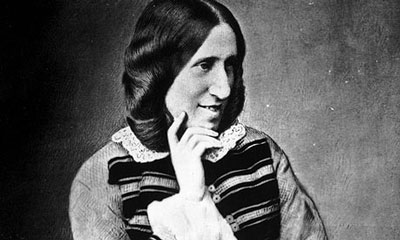

Geraldine Endsor Jewsbury was born on August 22, 1812, at Measham, near the Derbyshire-Leicestershire border, the daughter of Thomas Jewsbury, a cotton manufacturer, and his wife, Maria, a cultivated woman of artistic tastes. When she was six, Geraldine and her family moved to Manchester, and her mother died the following year. Her older sister, Maria Jane Jewsbury, who had become an accomplished poet, took control of the household and her sister’s education. After Maria’s marriage in 1832, Geraldine, was charged with the care of the Jewsbury household. After her sister’s sudden death the next year, and the illness and death of her father shortly afterward, Geraldine grew disenchanted with her milieu. She began a correspondence with Thomas and Jane Carlyle, who became her lifelong friends.

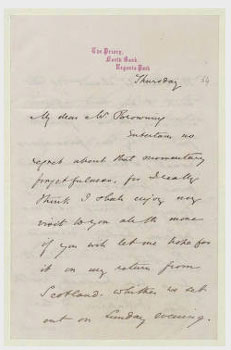

Her unconventional personality was reflected in her “novels of doubt,” which dramatized the loss of faith in orthodox Christianity and the quest for a new structure of belief. She wrote eight novels, six for adults, two for children. She also gained fame as a critic, a publisher’s reader, and a figure in London literary life. Her friends included Huxley, Kingsley, Rossetti, the Brownings, Forster, Bright, Ruskin and Lewes. Her book, The History of an Adopted Child (London: Grant and Griffith, 1853) was in the Brownings’ library.

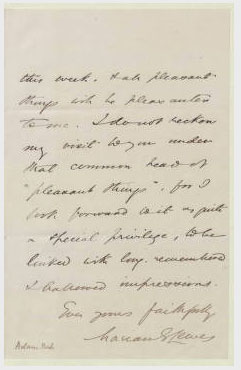

The Armstrong Browning Library owns one letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning, dated 11 December 1854, which anticipates Geraldine Jewsbury’s gift to EBB of her book, The History of an Adopted Child (1853). Another letter from her sister Maria Jane Jewsbury to Anna Jameson describes her impressions of Mary Shelley.

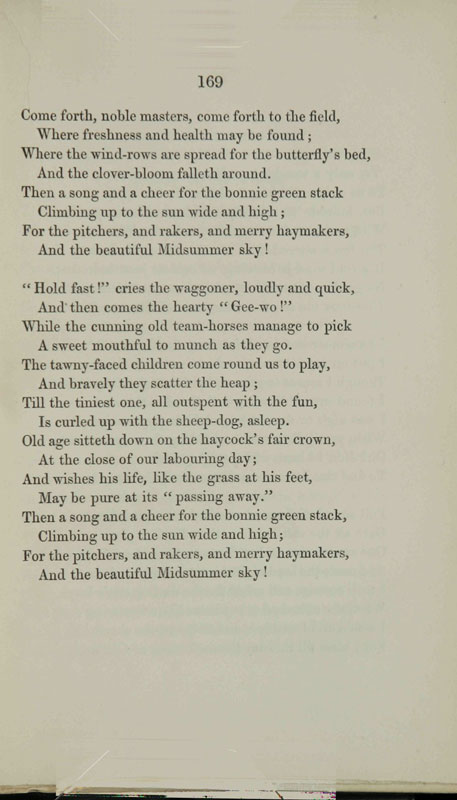

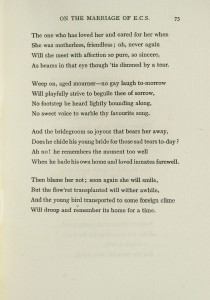

In 2012 the ABL acquired a commonplace book containing 17 pages of manuscript text and 27 very fine pencil drawings after engraved illustrations, bound in a claret morocco binding with gilt title, Gleanings, on the cover, dated 1832, and dedicated to “ā ma chēre soeur. Mars 26ēme 1832,” translated “To my dear sister March 26th 1832”. The volume is quite beautiful, and it inspired me to search for the Victorian sister who had created it. One of the first clues in the album was a poem, “The Florentine,” written by Maria Jane Jewsbury (1800-1833). A little more research led to her sister, Geraldine Jewsbury, and having compared a sample of her handwriting, our curator of manuscripts, Rita Patteson, agreed that this may well be the work of a juvenile Geraldine Jewsbury. Prior to 1830 the young Geraldine had spent several years at the Misses Darbys’ boarding-school at Alder Mills, near Tamworth, and then in 1830–31 she continued her studies in French, Italian, and drawing in London. Perhaps Geraldine demonstrated her expertise in the French language, her drawing skills, and her regard for her sister’s poetry by composing the book and giving it to Maria Jane as a wedding gift. (Another poem in the volume is “The Bride” by Felicia Hemans.) Maria Jane was married later that year, and traveled to India with her husband, where she died unexpectedly from cholera the following year. Geraldine tried to collect the rest of her sister’s unpublished works and belongings from her husband, but was unsuccessful. Geraldine’s inability to obtain her sister’s possessions could possibly account for the loss of the lovely friendship book until recently.

Melinda Creech

Frances Ridley Havergal. The Ministry of Song.