By Mark Sandy, Professor of English, Durham University, United Kingdom

Between August and September 2017, I held a one-month Visiting Scholars Fellowship to conduct research in the Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University, Waco, Texas, for my current book-length project, Transatlantic Transformations of Romanticism: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and the Environment (under contract with Edinburgh University Press).

Consequently, nestled away in Central Texas, a stone’s throw away from the Brazos River, my family (partner, Hazel, and son, Michael) and I discovered the unexpected charm of the Armstrong Browning Library, with its distinctive and beautiful wrought bronze doors, Italianate marble interiors, and iridescent stained-glass windows. All of these decorative features by the design of the library’s founder, Dr A. J. Armstrong, reflect the life and work of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. As you might expect, a large part of the library’s rare manuscripts and books collection is dedicated to the Brownings. As a scholar of Percy Bysshe Shelley, I was fascinated, for example, to peruse a copy of the same edition of Shelley’s Posthumous Poems held in Robert Browning’s personal library. But such findings are not the only precious treasures to be found here.

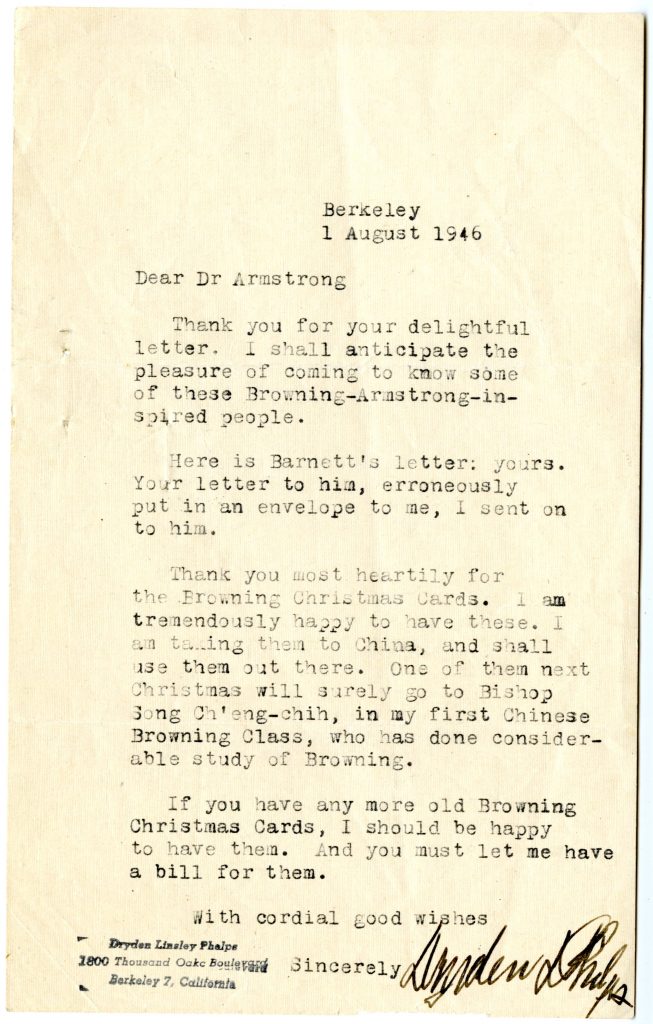

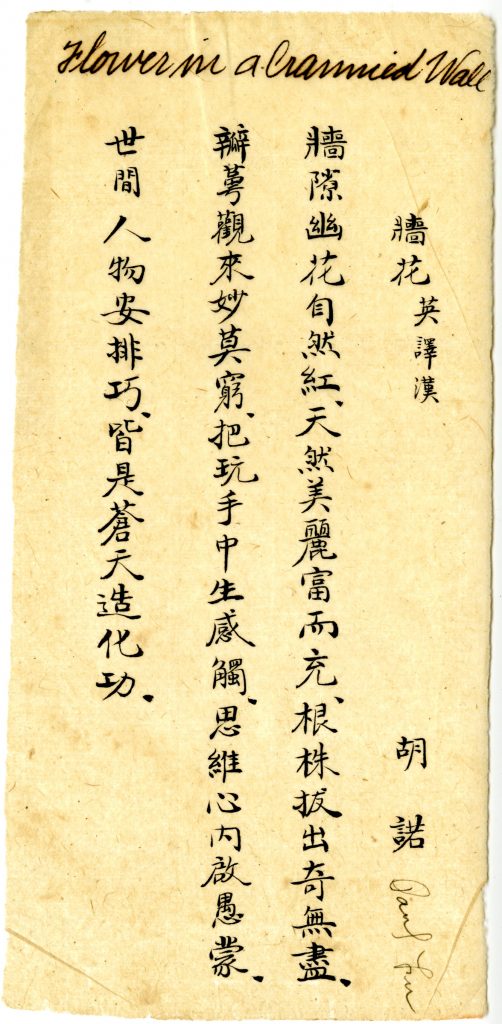

Outside of the Brownings’ circle, the collection of manuscripts, letters, rare books, and periodicals held at the Armstrong Browning Library reveal the life and work of other prominent nineteenth-century figures (including William Wordsworth, Thomas Carlyle, Felicia Hemans, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson) on both sides of the Atlantic. It was the possibility of what these holdings might tell about the intellectual, imaginative, and cultural transatlantic exchanges between Emerson and Thoreau and key British Romantic poets that, before I had experienced its architectural and contemplative charm (especially of the Foyer of Meditation echoic, on occasion, with choral singing), sparked my interest in the Armstrong Browning Library.

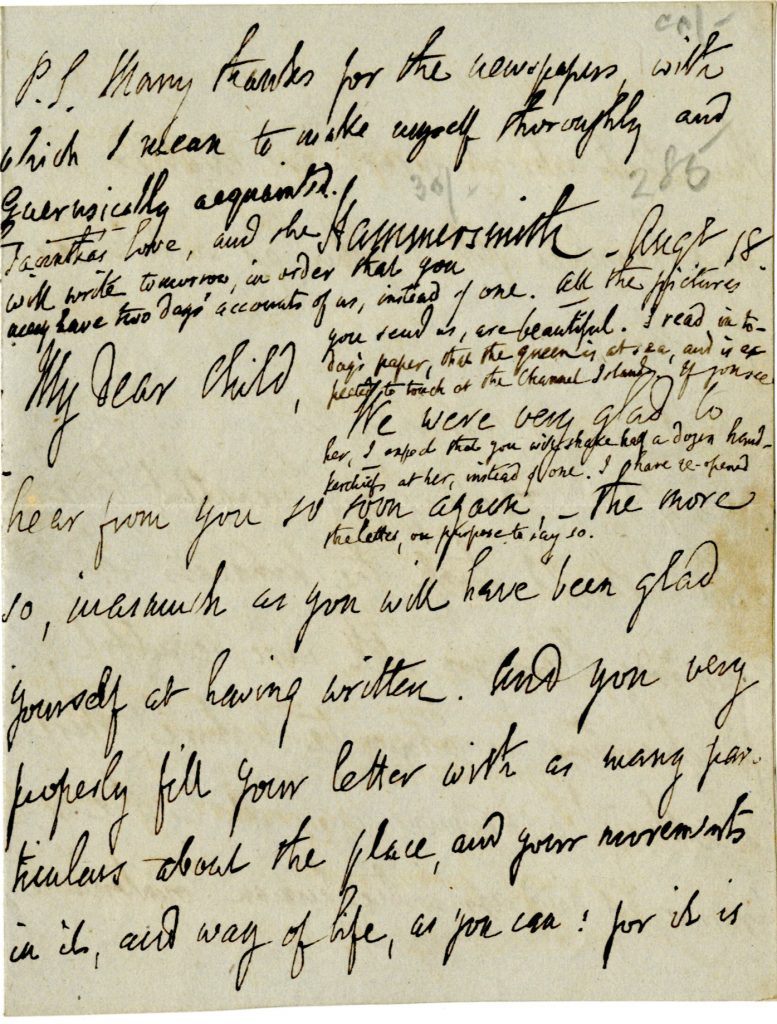

Exploring these transatlantic conversations between British and American writers is something of a daunting undertaking, so I concentrated my primary focus on the correspondence between William Wordsworth and his American editor, Henry Reed, as well as some unpublished letters of Wordsworth held at the Armstrong Browning Library. Amongst these unpublished materials of particular interest was a letter by William Wordsworth, dated 10 June, 1834, to John Heraud, author of The Judgement of the Flood. This letter, in Wordsworth’s hand on three pages and (on the basis of two letters with the same date) considered to have been composed at Rydal Mount, expresses the poet’s concern about having trouble with his eyes.

About a year earlier, Emerson’s account of his first visit (28 August, 1833) to Rydal Mount corroborates Wordsworth’s concerns about his poor eyesight. This concern with physical eyesight and poetic vision helped inform an article I was completing on “‘Strength in What Remains Behind”: Wordsworth and the Question of Ageing’ (forthcoming in a 2018 special issue of Romanticism on ‘Ageing and Romanticism’, edited by Jonathon Shears and David Fallon), as well as speaking to Emerson’s emphasis on the image of the all-seeing and clear-sighted ‘transparent eyeball’ (Nature). These observations will inform the discussion of the introduction to my study of Transatlantic Transformations of Romanticism.

After this initial foray into Wordsworth’s correspondence, I wanted to cast my net more widely within the Armstrong Browning Library collection in order to arrive at a deeper understanding of the interactions (positive and negative) of Emerson and Thoreau with the ideas, thoughts, and works of the British Romantics (including Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Keats, and Shelley). Pertinent copies of American printed nineteenth-century editions and anthologies of British Romantic writers accessible at the Armstrong Browning Library, included The Poetical Works of S.T. Coleridge (New York, circa 1888) and The Works of Lord Byron (New York, 1845), as well as anthologies, such as British Poets of the Nineteenth Century (Chicago, 1929).

With these earlier editions and anthologies, I was able to arrive at a much more fine-grained understanding of which particular works by British Romantic poets were in circulation in the United States and, by cross-checking with bibliographical records of Thoreau’s personal library and Emerson’s library borrowings, which works especially were likely to have been read by Emerson and Thoreau. My task was also helped by the fact that, on several occasions, as was the case with the edition of The Works of Lord Byron (New York, 1845; originally published 1835), owned by Thoreau, and the edition of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Essays, Letters from Abroad, Translations, and Fragments (London, 1840), read by Emerson, the Armstrong Browning Library owned the exact same or later edition of that publication.

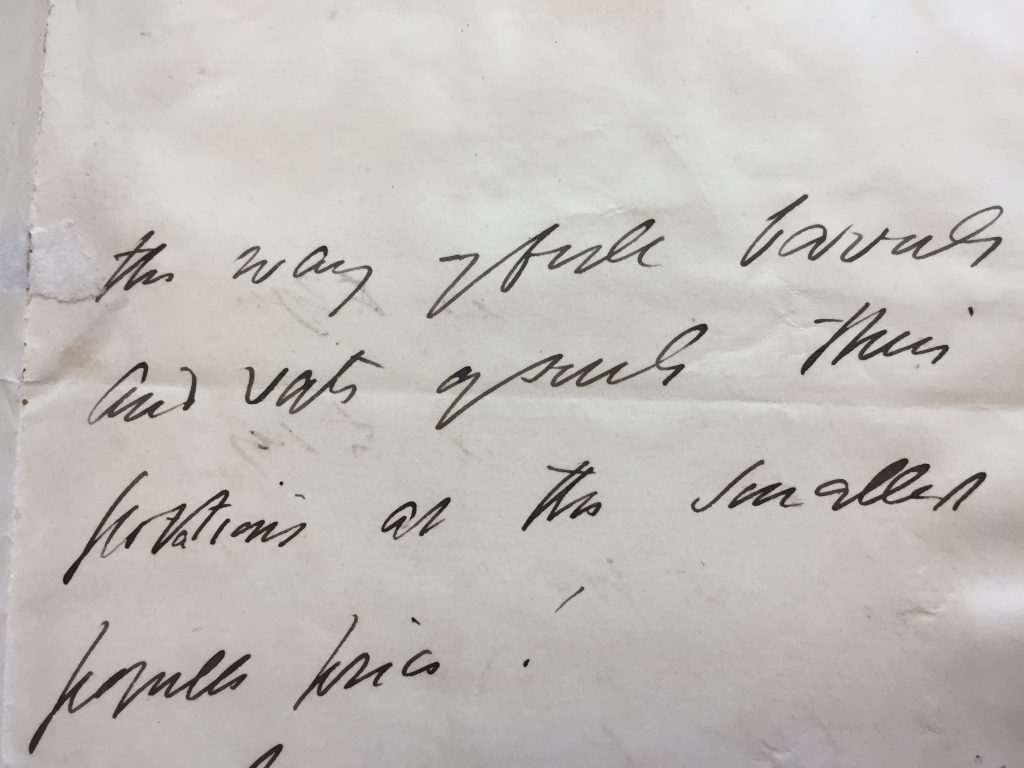

A manuscript edition twenty-volume set of The Writings of Henry David Thoreau. 20 Vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1906), signed by the publisher and containing an original leaf (in Thoreau’s hand) of his reflections on the idea of suffering in ‘The Sankhya Karika’ also provided further insights into Thoreau’s thought, more generally, and, more specifically, his particular responses to British Romantic poets. For instance, on observing the Charles River, one ‘cloudy evening’ in the summer of 1845, Thoreau is moved towards a sense of Wordsworthian things sublime and remarks, ‘“I was reminded of the way that in which Wordsworth so coldly speaks of some natural visions or scenes “giving him pleasure.”’ (Vol. 8, Journal II, p. 295).

Having the opportunity to investigate these personal and cultural exchanges, through using the nineteenth-century rare manuscripts and books collections at the Armstrong Browning Library, has greatly informed the underpinnings of my present book project’s larger mapping of these transatlantic transmissions and transformations of, as well as exchanges with, British Romanticism. On a more personal and pleasurable note of my own, I cannot thank the staff of the Armstrong Browning Library enough for all their unstinting helpfulness, good humour, kindnesses, and hospitality to both myself and my family during our visit.

![Letter from Sir Walter Scott to [Samuel Shepherd], 4 October 1825, intergral address.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2017/02/Scott4-2lp5f15-647x1024.jpg)