By Duc Dau, Research Fellow in English and Cultural Studies, The University of Western Australia

Dr. Duc Dau, Research Fellow in English and Cultural Studies, The University of Western Australia

In this blog post I hope to provide readers with an insight into some of my recent experiences as a visiting scholar at the Armstrong Browning Library (ABL) and the extraordinary privilege of being able to access unpublished or incredibly rare and precious manuscripts.

I am a research fellow in English and Cultural Studies at the University of Western Australia (yes, it’s very far away from Waco!). I specialise, among other things, in Victorian literature and theology, and am working on a book about the reception of the Song of Songs in Victorian literature and culture. I was awarded a visiting library fellowship at the ABL which I took up in February-March 2016. It was my first trip to both the ABL and Baylor University, and I hope it won’t be my last.

Last year Dr Joshua King, the Margarett Root Brown Chair in Robert Browning and Victorian Studies at the ABL, informed me that the library had strong holdings not simply on Robert Browning (RB) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (EBB), but also on Michael Field. Michael Field is the pen name of an aunt-niece couple, Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper, who wrote poetry and drama and kept a multi-volume journal. The ABL has a good number of first editions of their works as well as microfilm copies of their 30 volumes of journal material and 8 bound volumes of correspondence, held in the British Library. Most of the diary material and the letters remain unpublished. Given that I had started writing about the religion and love in EBB’s poetry and about death and conversion in Michael Field’s journals and poems, I decided to apply for a library fellowship and am grateful to have been successful.

One of the best things about being a researcher is having the opportunity to visit the most extraordinary libraries and to gain access to rare and priceless collections. The ABL is one such library. The ABL’s Belew Scholars’ Room is a beautiful and well-resourced location for scholarly research and contemplation. Within minutes of requesting material, the helpful staff are at one’s desk with the items. At the end of the day, the material is placed in one’s own cabinet. One rarely receives this kind of service elsewhere. Staff at the ABL have the wonderful opportunity of locating and purchasing nineteenth-century materials from around the world, and I have been regaled with stories of some of these purchases. Indeed, I have noticed that staff have a strong interest and investment in the library’s holdings and in the Brownings. This passion for the subject matter translates into their work and in their desire to help one make the most of one’s visit to the ABL.

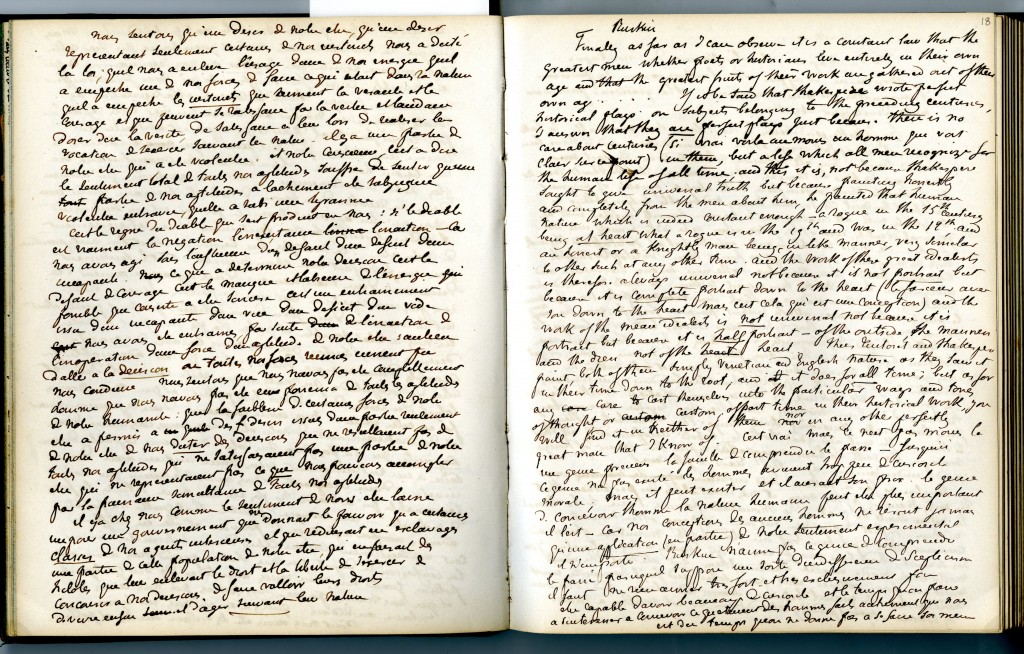

“Sonnet 43,” in EBB’s hand, from Sonnets from the Portuguese (D0876)

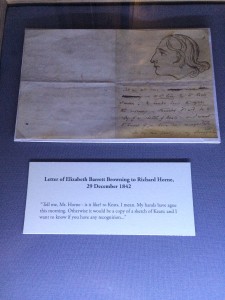

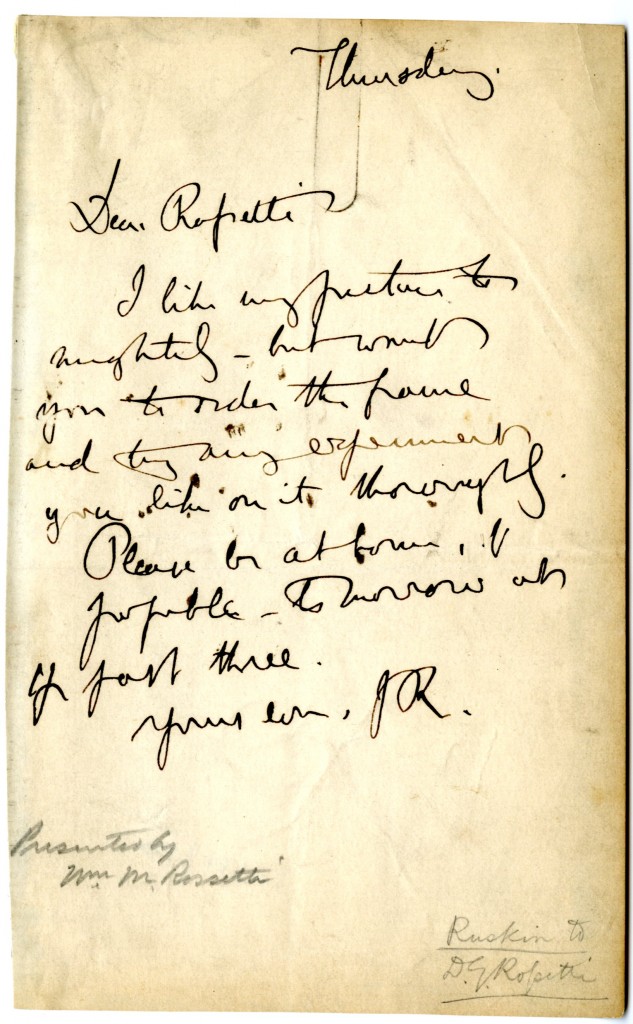

Researchers are afforded the privilege of accessing and touching (and, for some of us, secretly smelling) handwritten manuscripts and letters written by long-dead authors. These items are usually locked away and not normally available to the general public. For the tactile among us, there’s a certain thrill at the experience of touching these manuscripts and bits of paper. It’s a thrill that few, apart from literary scholars or die-hard fans, would understand, let alone know existed. I was able to view and touch one of the ABL’s most precious items, one of only three extant copies of EBB’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, written in her hand. The sonnets are now part of popular culture and are known and treasured by readers worldwide. In fact, I had emailed a friend and colleague at my university, telling her about the quiet pleasures of being able to access something such as EBB’s handwritten Sonnets from the Portuguese. A few days later she emailed to inform me that when she mentioned my trip to a friend of hers, her friend immediately gushed that she had been reading EBB, admired her work, and thought how wonderful it would be to read the original letters between EBB and RB.

Alas, EBB’s handwriting can sometimes be difficult to decipher and therefore the pleasure of seeing and feeling the pages is blunted by a degree of frustration, at least for me, at the inability to read the words. Such was the case when I first encountered her writing: her notes on two of her Bibles housed at a library elsewhere. I was therefore pleased to discover at the ABL that all her poems have all now been published, so I could divert my attention elsewhere, such as the wealth of secondary materials and historical reviews relating to EBB’s poetry.

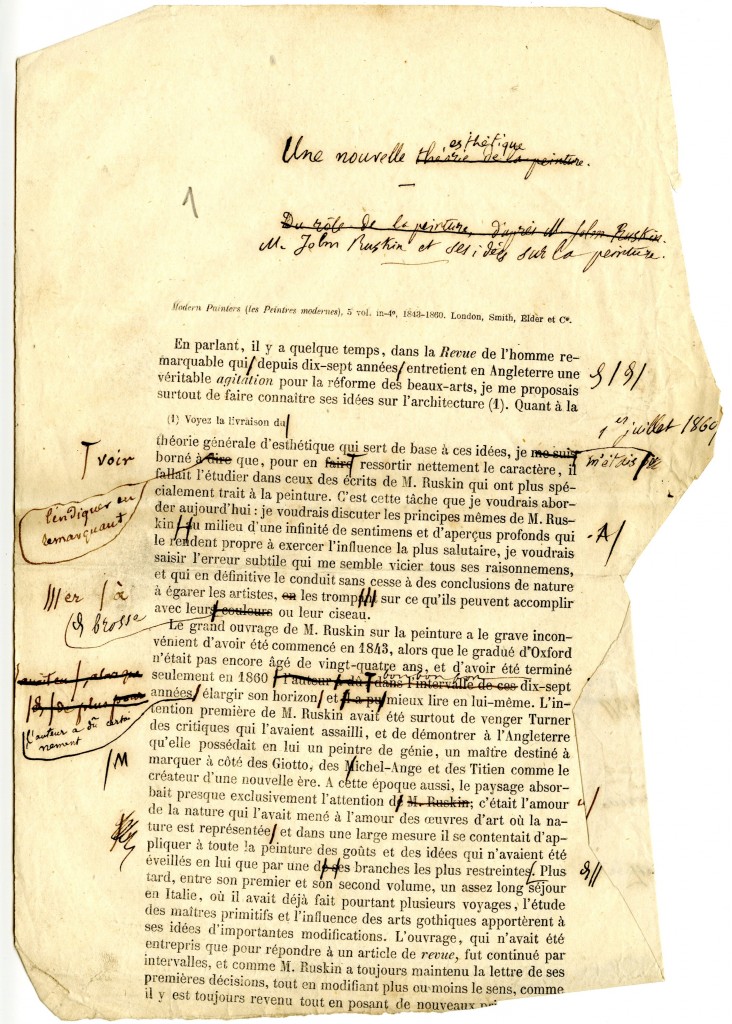

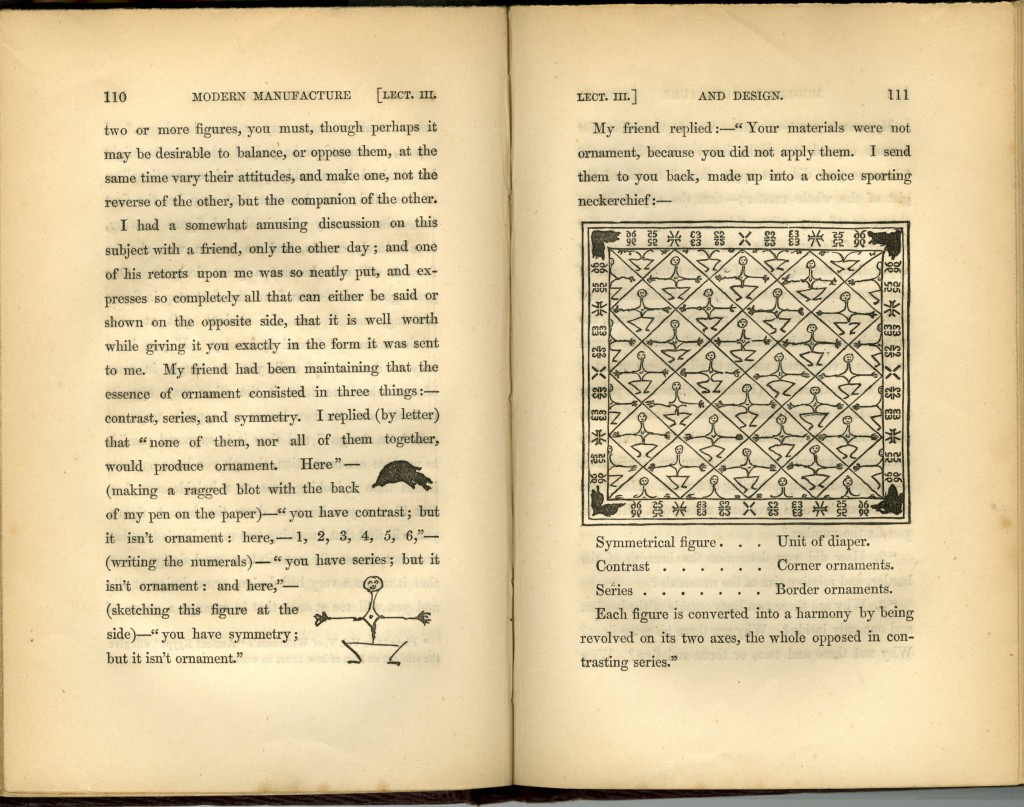

A page from Line upon Line in which EBB has altered the text to meet her approval (ABLibrary Brownings’ Lib X BL 220.95 H362l v.1-2)

The ABL has acquired items from EBB and RB’s library over the years, and one of the most fascinating books that ABL librarian Cynthia Burgess found for me was a two-volume religious instruction guide for their son Pen. Line upon Line; or, a Second Series of the Earliest Religious Instruction the Infant Mind is Capable of Receiving interprets the Bible through a Christian lens, acting as a didactic tool for children. What I found most fascinating was the fact that EBB had altered select passages to her liking. Every so often a word, several words, or even an entire sentence, would be altered, whited out, to meet her approval. Sometimes these sections are left blank, but usually EBB has written (legibly) over them. Ever the poet, she would occasionally seek to improve on the didactic rhymes dotted throughout the two volumes. Thus, being able to access such items owned and altered by EBB offers scholars an insight into her religious thinking and indeed her personality. At the ABL I was able to delve deeper into my work on the kinds of romantic, religious, and communal love based on Song of Songs imagery in EBB’s works.

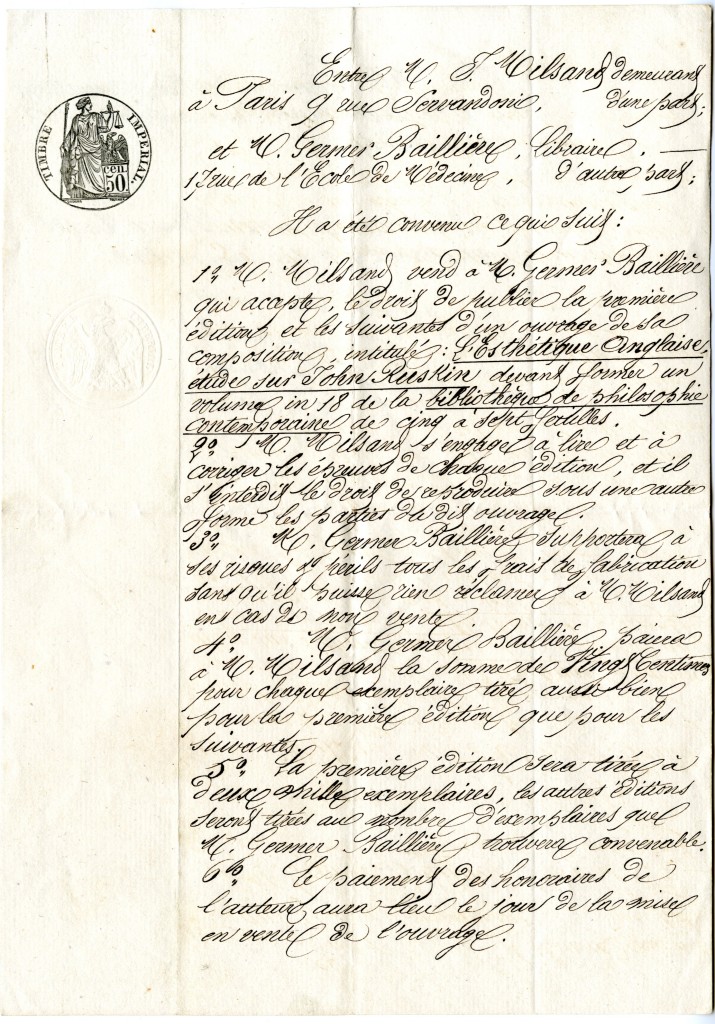

I had worked with the original Michael Field material at the British Library, but left much of it untouched as a result of time restraints. At the ABL I had free access to the collection on microfilm, which saved me a great deal of time. My work on Michael Field focuses on how passages from the Song of Songs appear when the authors write about death, particularly at the deaths of Edith’s mother, their mentor and literary hero RB, and their beloved dog Whym Chow. At the ABL I focused on their letters to Browning and on their journal entries written around the time of their conversion to Roman Catholicism and Edith’s final months before her death from cancer. While Edith and Katharine wrote their journal for posterity and publication, they could not have known the identities of their future readers and that I would be one of them, scrolling through their journals in the small microfilm room at the ABL.

Edith and Katharine’s grief at the loss of loved ones is profound in their journals and letters. Their writing about grief furnishes scholars with compelling insights into Victorian mourning, their love of animal companions, and the complex feelings associated with the conversion experience. The poets’ grief at the death of Whym Chow runs over many, many pages, much of it unpublished. They expressed their wish to be reunited with him after death. They wrote a book of poems about him titled Whym Chow: Flame of Love. He was the “flame of love,” whose death, they believed, was the tragedy that brought them into the arms of the church.

For scholars, researching about death and writings concerned with death is never a happy task. It was poignant to see Edith Cooper’s writing deteriorating noticeably in the months leading up to her death from cancer. She had refused painkillers and was in extreme pain. Unlike a novel, a journal does not have a typical beginning or ending; as she wrote she could not have known when her last breath would be. At one point, Edith talks about receiving Viaticum, the Eucharist given to a person in danger of death. At the time she must have thought she was living her final hours. But she was to live and suffer for a few more months.

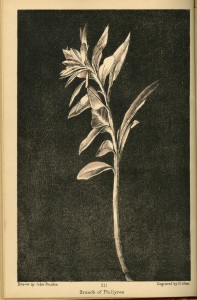

In the final months she wrote often about flowers, whether they be from the garden, or gifts, or offerings on the altar. She often spoke about lilies and roses. On the day she wrote about “my Solemn Vow of Chastity” Edith says, “So the crucifix is ‘inter lilia’, as the Beloved is among the spouses in Paradise; & ‘inter lilia’ in His real earthly Presence, as the Holy Host, He will rest when he comes to our Home.” The Latin phrase “inter lilia” means “among the lilies,” and derives from the Song of Songs. In this entry, the poet uses the biblical reference to describe lilies on a shrine and then progresses to its rich, theological significance about spiritual purity, union with the divine, and the incarnation. Elsewhere in the journal, Edith reflects on prematurely blossoming roses, “[t]heir rich, marvellous blossoming [that] fades as a very dream.” One feels that she might also have been reflecting on her own premature demise; she would die relatively young, at the age of 51.

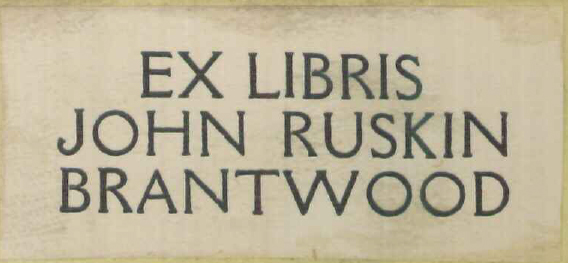

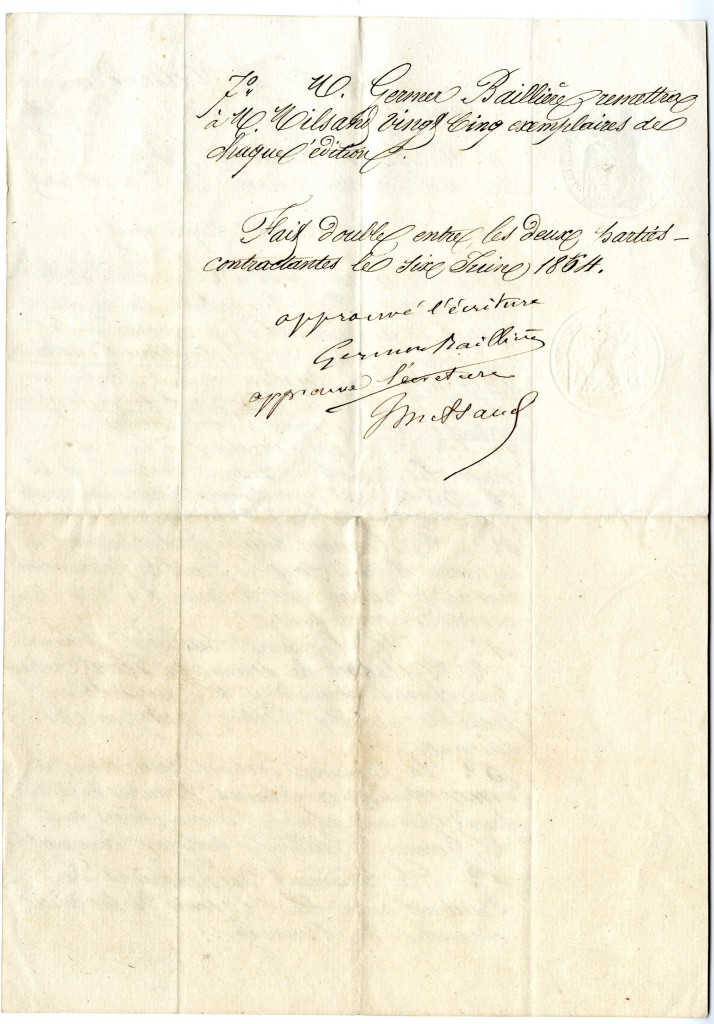

RB’s copy of The Father’s Tragedy, Etc., by Michael Field, inscribed: “R. Browning Esq./with sincere regards./Michael Field./June 8th 1885.” (ABLibrary Brownings Lib X BL 821.89 F445f)

I’d like to conclude by saying that, while much of the intellectual work at the ABL occurs among books and manuscripts (among the lilies of the library, as it were), I also found many moments of intellectual stimulation from the lively conversations about poetry, religion, politics, relationships, and Texas with staff and graduate students in the reading rooms, corridors, and kitchen. I was also able to meet or catch up with some of the leading scholars in my field at the library’s fantastic “The Uses of ‘Religion’ in 19th Century Studies” Conference, held in the final week of my visit. All these factors contributed to making my trip to the ABL so pleasurable and memorable.

Dr Duc Dau is a research fellow in English and Cultural Studies at The University of Western Australia, whose position is funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award. Author of Touching God: Hopkins and Love (2012) and co-editor of Queer Victorian Families: Curious Relations in Literature (2015), her articles have appeared in such journals as Literature and Theology, Religion and Literature, The Hopkins Quarterly, Victorian Literature and Culture, and Victorian Poetry.

To learn more about the Armstrong Browning Library’s Visiting Scholars Program, visit our website.

![Letter from John Ruskin to [William] Kingsley. 18 February 1886. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-William-Kingsley015-1nh5387-658x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to Tom Taylor. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Taylor014-1bq7kpb-673x1024.jpg)

![Letter from John Ruskin to [Unknown]. [Undated].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Unk-14a52wp-807x1024.jpg)

![John Ruskin to Mrs. Johnson. [31 January 1865].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Johnson-1-16kewxa-641x1024.jpg)