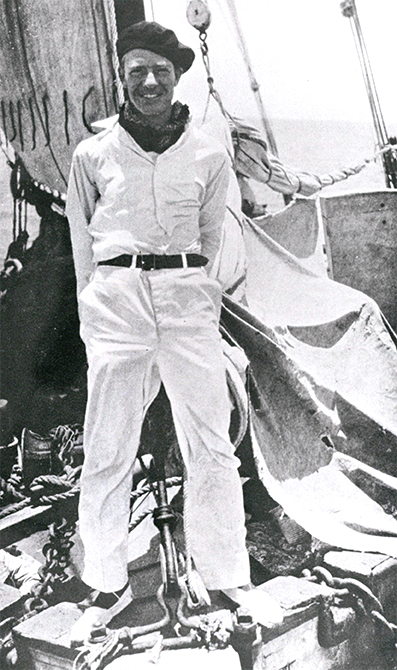

By Gerard Wozek

In anticipation of the Armstrong Browning Library & Museum’s Browning Day Celebration on April 16, we are excited to present a recently completed video poem titled, “Not Death But Love,” produced by myself, Gerard Wozek as writer, and directed by artist Mary Russell in collaboration with Rob Kurland. In this brief film collage, it is our intention to honor the buried personal history of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. By reimagining her meditative garden strolls, our poetry video seeks to reveal her abiding love with her husband Robert Browning, her deep affinity for nature, her later experiments with the occult, and her ability to transcend the boundaries of time.

In anticipation of the Armstrong Browning Library & Museum’s Browning Day Celebration on April 16, we are excited to present a recently completed video poem titled, “Not Death But Love,” produced by myself, Gerard Wozek as writer, and directed by artist Mary Russell in collaboration with Rob Kurland. In this brief film collage, it is our intention to honor the buried personal history of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. By reimagining her meditative garden strolls, our poetry video seeks to reveal her abiding love with her husband Robert Browning, her deep affinity for nature, her later experiments with the occult, and her ability to transcend the boundaries of time.

My creative partner Mary Russell and I have had the idea for years to develop a tribute video that honors Elizabeth Barrett Browning, her life as a writer and what informed her creative process. Our keen interest in the life of the poet really hit a peak when we were teaching in a study abroad program offered through our university that took us to Florence, Italy. There we discovered Barrett Browning’s attraction for long strolls in the Florentine Boboli Gardens and her life at Casa Guidi. We were so enchanted with what we discovered about the life of the poet in Italy, that we at once began to put together the idea of “restaging” and reimagining her walks alongside a narrative that would serve as an homage to the poet’s craft and genius.

I developed a tribute poem that would take the reader and listener on a journey through various elements and time periods inhabited by Barrett Browning. I wanted the viewer to feel as though they were walking alongside the poet, in order to not only see what she might be encountering in the Boboli Gardens of Florence, but also to feel and connect with her internal creative vision:

We listen for Pan’s pipes. A leopard’s growl as it grazes the bark of an overgrown cypress. Your hushed voice moving through the lines of a sonnet.

Elizabeth! Your handwriting is the black-ink edge of a storm cloud curling into infinity.

Puffs of red dust that once clung to your petticoat, now stain our sandal straps as we make our way to the Egyptian obelisk.

Poetry video is a unique way of expressing this particular kind of tribute to a poet. Also known as videopoems, cine-poetry, or poetry films, poetry video unites spoken text (or sometimes text that is written on the screen or text that is simply interpreted by the visual artist) with imagery and music. Situated somewhere between installation art and music video, poetry video is an evolving genre. When a resonant image couples with the poet’s text, alchemy can occur between the two disciplines of poetry and film. The visual images often deepen the author’s meaning, provide startling contrast, or locate new alliances within the inherent metaphors of the poet’s text. Stills, animation, computer graphics, and filmed imagery, complimented often by a soundtrack and/or the poet’s voice, can broaden and enhance the experience of the listener/viewer.

“Not Death But Love,” which was completed earlier last year, will screen this summer at the 2021 International Poetry Video Festival in Athens, Greece. We were so thrilled that Jennifer Borderud, Director of the Armstrong Browning Library at Baylor University, offered us an opportunity to share our newly completed work with the community at Baylor, and most especially with those individuals who will celebrate the University’s annual Browning Day held virtually on April 16, 2021.

The video is available below. You can also contact me at Gerard.Wozek@gmail.com for more information about the video.

The Armstrong Browning Library & Museum’s annual Browning Day Celebration will be held virtually this year on April 16. For more information, visit baylor.edu/library/browningday.