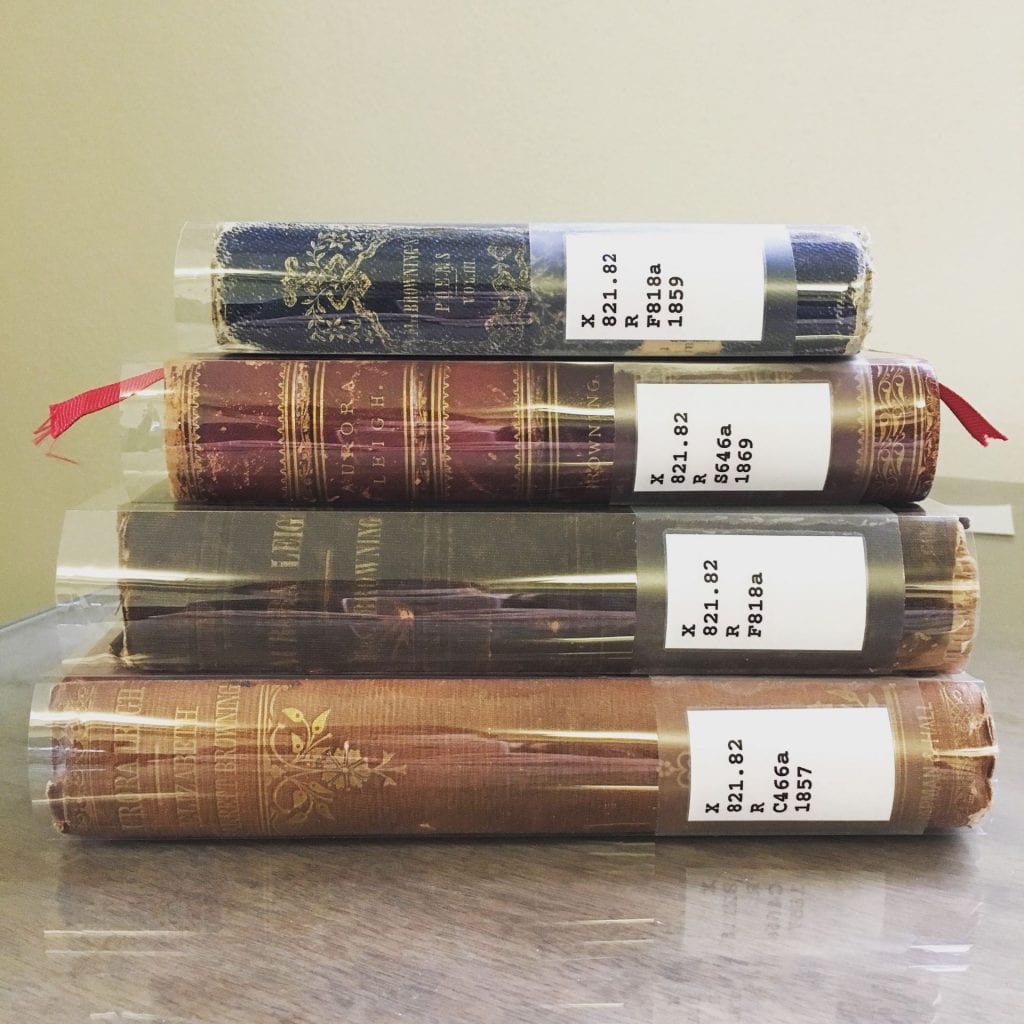

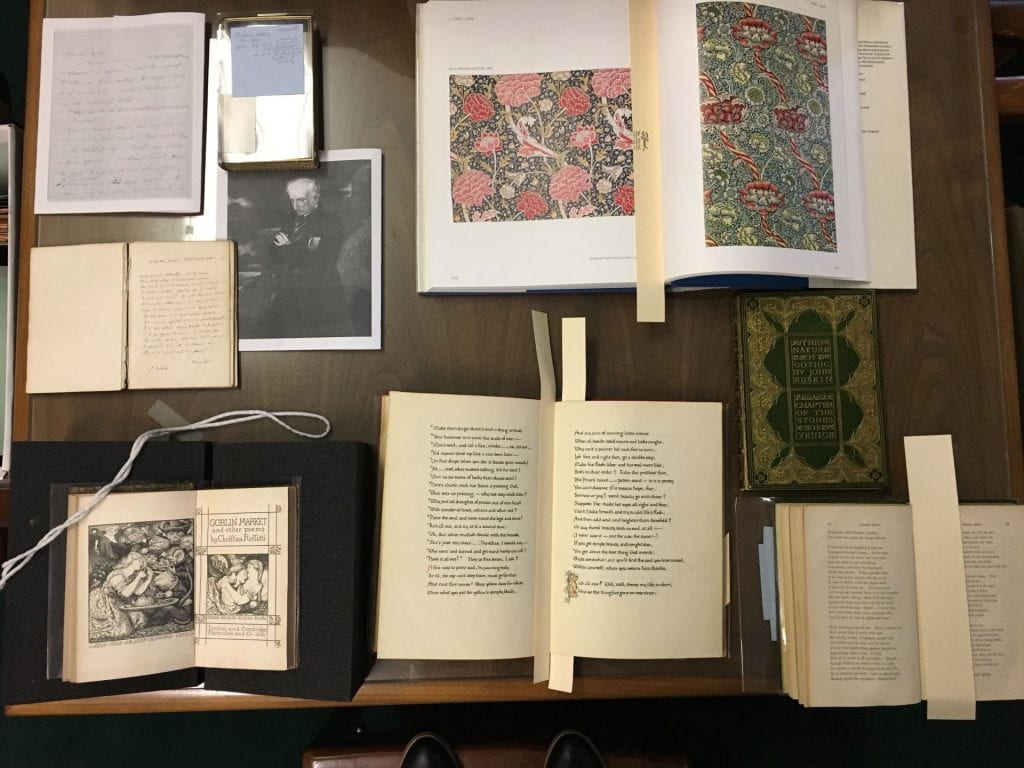

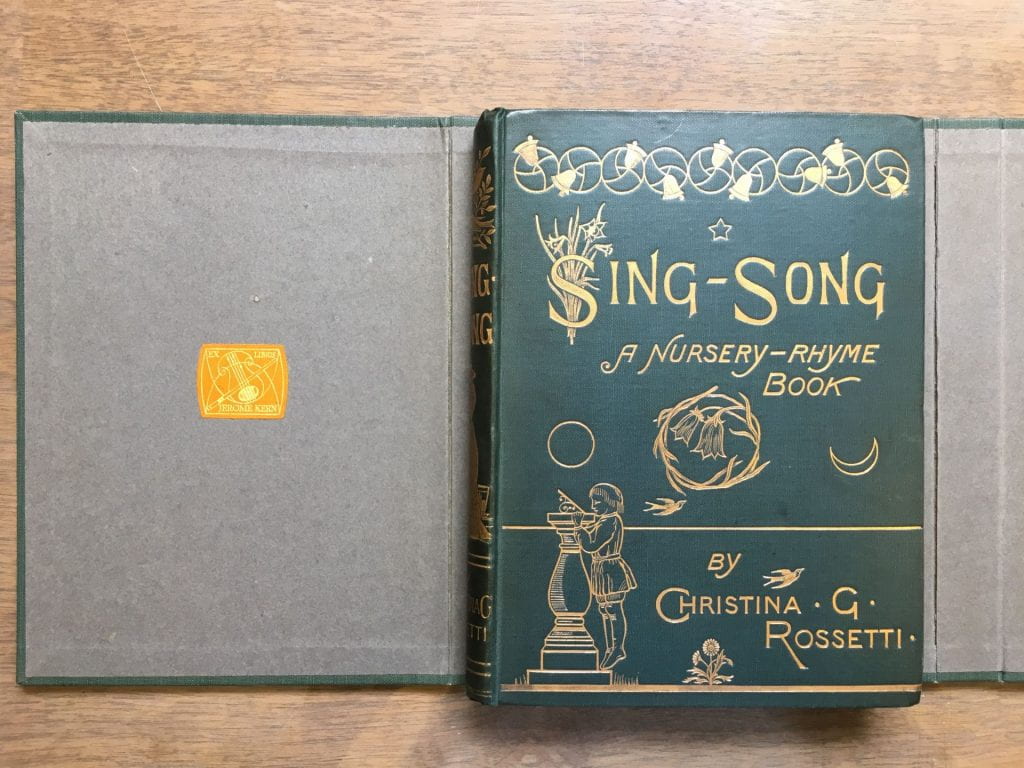

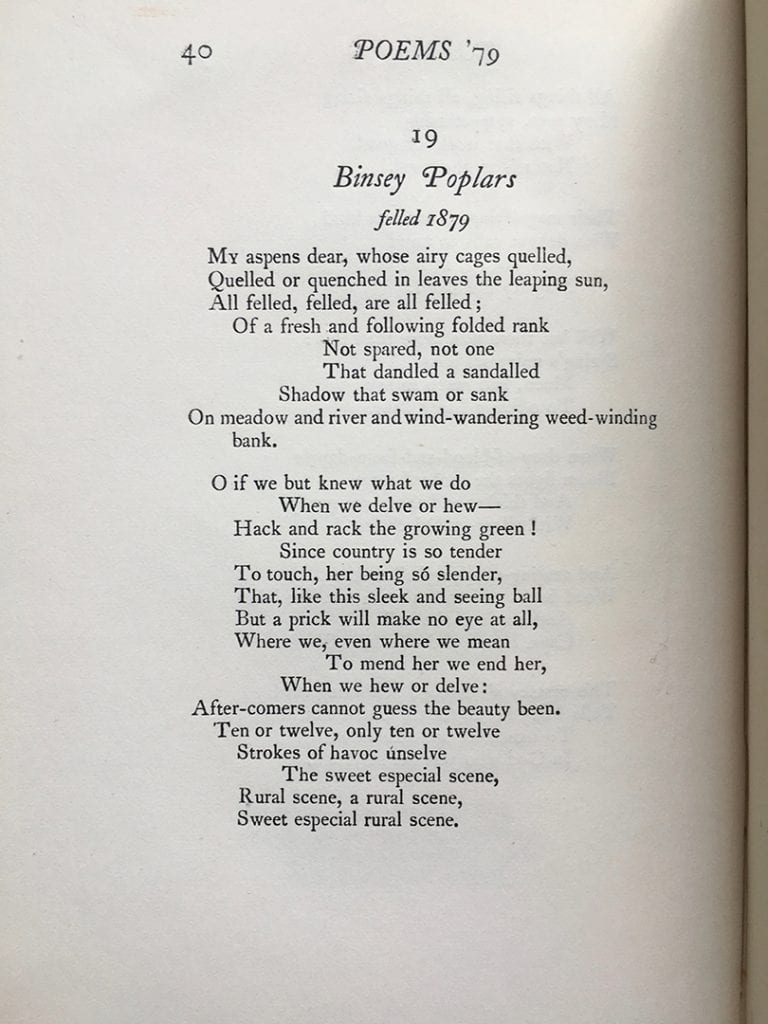

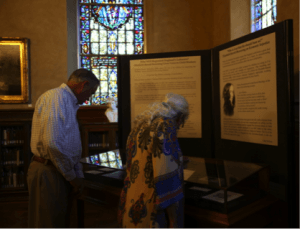

On December 9th at 9:05am, Dr. Kristin Pond’s English 3351: Literary Networks in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Centuries course will be presenting their Great Exhibition. This is a class project which requires students to explore what artifacts, including original letters, manuscripts and books, photographs, and actual objects exist at the Armstrong Browning Library related to each student’s assigned author.

The exhibition will be on display in the Hankamer Treasure Room for the entire morning December 9th, 2019.

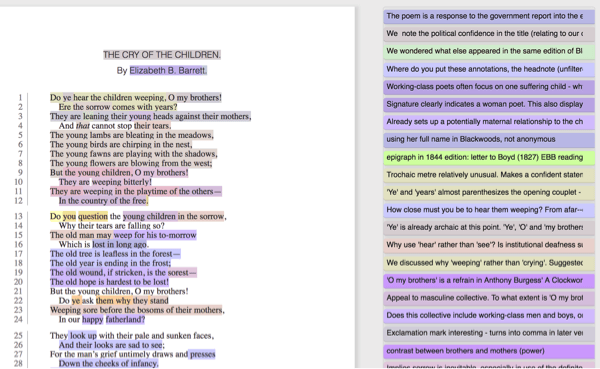

To prepare for the exhibition, students wrote a short biography of their author and practiced analyzing an artifact for what it reveals about their author. A sample of one student’s preliminary research follows.

The Life and Literary Connections of Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens was born in 1812 as the second of eight children. His parents did their best to make ends meet, but they were a poor family, and his father was sent to debtor’s prison in 1824. Because of this, Dickens dropped out of school and was forced to work in a factory in order to help provide for his family, spending long hours at a job that gave him meager pay in exchange for his labor. Although he returned to school for a short time, he was forced to give it up again, this time going to work at a newspaper, where his career quickly took off. He began as a reporter and quickly began writing his own short stories, which eventually lead to the writing and ‘conducting’ of his own middle class periodical, Household Words, which was later followed by All the Year Round. Dickens married Catherine Hogarth and had ten children, but his life fell apart in the 1850s with the death of two of his children and a dramatic separation from his wife. He was also known to have had an affair around the time of the end of his marriage with a much younger girl named Ellen Ternan. He wrote fifteen novels throughout his life and died at age 58 with his last work uncompleted.

One of Dickens’s most influential relationships in his lifetime was Wilkie Collins, a man twelve years his junior, who he met in 1851 when Dickens was already at the height of his career, having already published multiple novels and launched Household Words. They met by acting in a play together, and Collins quickly became one of Dickens’s most frequent travel and correspondence companions, forging a friendship which would last until Dickens’s death two decades later. Their literary relationship began with the contributions of Collins to Household Words and eventually morphed into a partnership in multiple works such as The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices, Frozen Deep, and The Wreck of the Golden Mary. Collins provided Dickens with a welcome respite from the collectedness and decency that was expected from him as a public figure of his status. Michael Slater, an author who spent much of his career studying Dickens, writes in his biography, Charles Dickens, that he “seems… to have found the younger man’s Bohemian attitude attractive” (Slater, 383). In some ways, the relationship between Collins and Dickens was extremely beneficial for them both, as Dickens’s experience and status complemented well the prodigy and playfulness of young Collins. He gave Dickens the opportunity to feel free from his constraints as a celebrity while also challenging him intellectually as a writer.

Although Dickens was an avid writer of letters, he burned all correspondence that he received so no letters to him exist today; however, there is a plethora of letters that are documented from him to others, including many written to Collins. In these letters, it is easy to discern the care that they felt for one another. One such letter from Dickens says, “I always feel your friendship very much, and prize it in proportion to the true affection I have for you” (Letter [25 May]). Collins even dedicated one of his novels, Hide and Seek, to Dickens as “a token of admiration and affection” (Wilkie Collins Info). Dickens thought highly of his friend’s writing, and, after reading Collins’s ‘The Diary of Anne Rodway’ on his train home he was so moved that wrote to Collins, “My behavior before my fellow-passengers was weak in the extreme, for I cried as much as you could possibly desire. . . . I think it excellent, feel a personal pride and pleasure in it, which is a delightful sensation, and I know no one else who could have done it.” These men deeply appreciated the intellect and companionship of one another, and they spent much of their time together critiquing, dreaming, and discussing as they travelled and wrote together.

However, there are some downsides to Dickens finding such a similar companion. Slater points out in his biography that in 1854 Dickens writes to Collins encouraging him to join him in London in his “career of amiable dissipation and unbounded license in the metropolis.” Later in the letter Dickens states, “If you will come and breakfast with me about midnight… I should be delighted to have so vicious an associate” (Slater, 384)(Letter [July 1854]). They were known to often frequent the streets of London and Paris late into the night, and Slater refers to Collins as the friend who “helped to provide Dickens with a desperately-needed new outlet or distraction” (Slater, 406). It could be argued that Collins assisted rather than stopped Dickens when he found himself infatuated with a young actress, Ellen Ternan, whom he saw perform. It is probable that one of the motivations behind the creation of The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices was so that Dickens and Collins could have a reason to travel Europe and meet up with her multiple times across the cities. In short, Dickens was a man who tended to make decisions based on what he was feeling, and because Collins was also known for being a bit looser in mannerisms, their close association did not help either one of them.

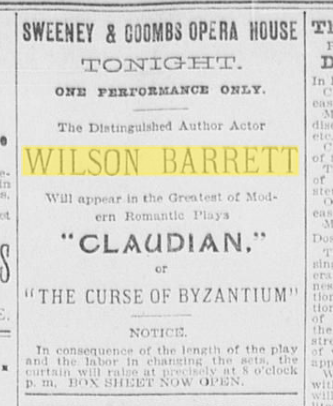

Apparently, this mindset that Dickens possessed bled into his writing in a noticeable way, many readers of his time and later periods found difficulty in reconciling him as a person with the literature that he produced. Elizabeth Barrett Browning is one of those critics, and she writes to a friend that she “was not such an enthusiast as people call themselves… but that he makes me feel his power again and again…” (Browning, Elizabeth Barrett). There were many who, like EBB, were skeptical of his approach to life but at the same time were compelled to his work due to his brilliance as a developer of characters and plot. It is very likely that Collins had something to do with the way that Dickens’ writing and lifestyle pushed boundaries more than was comfortable for readers such as EBB. Charles Dickens’s friendship with Wilkie Collins was one that brought the world a unique brand of literature, a brand that combined old and new, expert and amateur. Without this friendship, the literature that we associate with Dickens would not only be different, but it would be incomplete.

Works Cited

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett. Browning, Elizabeth Barney to Mitford, Mary Russell. 13 June 1843. In The Browning Letters, http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu

“Charles Dickens.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 29 Aug. 2019, www.biography.com/writer/charles-dickens.

Dickens, Charles. Dickens, Charles to Collins, Wilkies. 13 April 1856. In Letters of Charles Dickens to Wilkie Collins. Edited by Laurence Hutton. https://jhrusk.github.io/wc/letters

Dickens, Charles. Dickens, Charles to Collins, Wilkies. 25 May 1858. In Letters of Charles Dickens to Wilkie Collins. Edited by Laurence Hutton. https://jhrusk.github.io/wc/letters

Dickens, Charles. Dickens, Charles to Collins, Wilkie. July 1854. In Wilkes Collins and Charles Dickens.

Letters of Charles Dickens to Wilkie Collins, jhrusk.github.io/wc/letters/letters.html.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. Yale University Press, 2009.

WILKIE COLLINS AND CHARLES DICKENS, wilkie-collins.info/wilkie_collins_dickens.htm.

https://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/the-great-friendship-of-charles-dickens-and-wilkie-collins