By Allison Scheidegger, PhD Student, Department of English, Baylor University

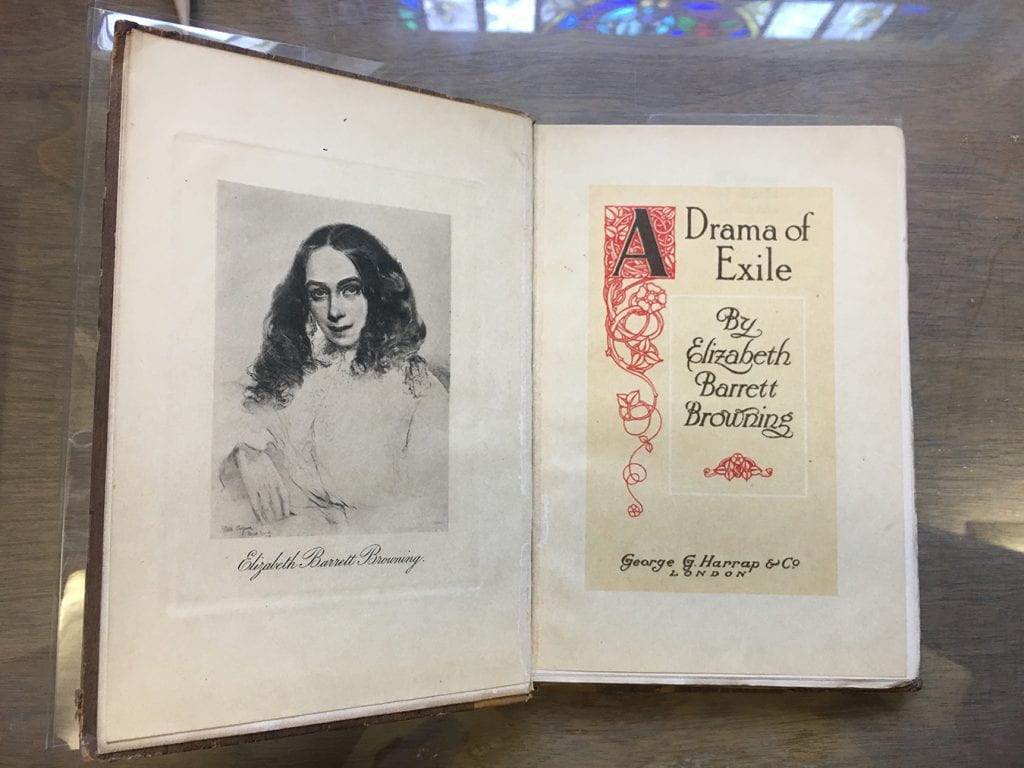

This spring, the Armstrong Browning Library is hosting “Puppy Love: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships,” an exhibition on dog ownership and depictions of dogs in the Victorian period, with a focus on Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, Flush. January 15, 2022 – August 15, 2022.

When friends asked me what I was doing this past summer, and I replied, “I’m curating a museum exhibit about dogs,” I always got one of two responses: “How cool!” or “How odd!” Both have been accurate. I should admit it: I’ve never been a pet person. I’ve kept a safe distance from dogs all my life, but I love the Brownings, and came to Baylor intending to write my dissertation on Robert Browning. When I saw the opportunity to spend time browsing the ABL archives and immersing myself in the Browning atmosphere, I immediately applied for the internship. I figured I could tolerate the dogs for the sake of the Brownings. I’ll tell the story of my personal puppy love journey in a later blog post, but for now, I want to share a peek into my process of researching Victorians’ interactions with their dogs.

“Puppy Love” began with the idea that it would be fun to do an exhibit on Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, Flush. As I explored Flush’s story alongside secondary sources on pet ownership, I realized that Flush’s story reflects major themes of nineteenth-century pet ownership. And once I expanded my focus to include Victorian dogs more broadly, I realized how much we have in common with the Victorians.

Our modes of expressing our affections have morphed—the Victorians wrote poems; we make posts on doggy Instagram accounts—but the sentiments haven’t. We own “fur babies,” call ourselves “dog moms/dads,” and, like the Victorians, lavish time, money, and energy on our pets. We also face similar social, economic, and ethical issues as a result of the large role of pets in our lives: we have to carefully evaluate if we can make the commitment to caring for a dog; we lament the inhumane breeding practices of puppy mills and worry about dogs left unadopted in shelters. As an increasingly wealthy middle class became interested in the companionship and status that dogs could offer, dog ownership spiked in the Victorian era, leading to the emergence of these same issues.

Because I tend to become bogged down in the details, I tried to keep long-term goals in mind in order to maximize my research time. I first read secondary articles about Flush to get a broad view of his story and the current scholarly conversations surrounding him. Instead of beginning by working through all of E. B. Browning’s letters looking for mentions of Flush, I used the digitized letters database, which provides both scans and transcripts of the Browning letters. Using the database greatly reduced the number of artifacts that had to be brought out of the archives: I could quickly isolate and evaluate relevant letters with simple keyword searches for “Flush” or “dog.”

Once I’d identified and retrieved potential artifacts, it was time to do mock exhibit layouts!

My initial layouts were very rough, and I was overwhelmed by the sheer number of decisions to be made. But in the end, doing physical layouts was the most challenging and exciting part of curating the exhibit. In most of my academic projects, I only arrange words. I enjoyed working with objects that have texture, color, and shape, and I learned so much about effective communication through the process of designing the physical layout. So many factors have to be considered: the space constraints of the exhibit cases, the fragility of the artifacts, the best way to display artifacts. Often, I would come to a layout with a plan in mind, only to realize that my plan wouldn’t work in the exhibit space. The practical limitations of my space and my materials kept my project grounded in practical communication concerns: I had to consider, above all, what would be most interesting and accessible to my audience. Thinking within the genre of the museum exhibit has trained new communication muscles. Often in writing for an academic audience, I don’t think about whether I am expressing myself as clearly as possible, but this project has taught me that clarity and accessibility should always be a primary concern. If my audience isn’t engaged by my writing, why write?

My initial layouts were very rough, and I was overwhelmed by the sheer number of decisions to be made. But in the end, doing physical layouts was the most challenging and exciting part of curating the exhibit. In most of my academic projects, I only arrange words. I enjoyed working with objects that have texture, color, and shape, and I learned so much about effective communication through the process of designing the physical layout. So many factors have to be considered: the space constraints of the exhibit cases, the fragility of the artifacts, the best way to display artifacts. Often, I would come to a layout with a plan in mind, only to realize that my plan wouldn’t work in the exhibit space. The practical limitations of my space and my materials kept my project grounded in practical communication concerns: I had to consider, above all, what would be most interesting and accessible to my audience. Thinking within the genre of the museum exhibit has trained new communication muscles. Often in writing for an academic audience, I don’t think about whether I am expressing myself as clearly as possible, but this project has taught me that clarity and accessibility should always be a primary concern. If my audience isn’t engaged by my writing, why write?

While curating this exhibition has challenged me as a thinker and writer, it will challenge me most as a teacher. I teach English composition at Baylor, and will teach British literature in the future. Curating this exhibit has made me rethink the way I structure my classes, forcing me to ask questions like “Am I stating the main point as clearly and simply as possible? Are the time blocks, sequencing, and activities in a class period all contributing to meaningful student interaction with our learning objective?” My internship also made me aware of opportunities for connecting students with the resources the Armstrong Browning Library offers. Many students who are accustomed to using only online resources are intimidated by the prospect of walking into a library and requesting physical artifacts. This summer, I learned that the ABL offers instruction sessions and teaching fellowships for faculty and graduate instructors who want their students to work with rare items relating to their class theme. I plan to use these resources when I begin teaching British literature next year.

Work Cited

Findens’ Tableaux: A Series of Picturesque Scenes of National Character, Beauty, and Costume. Edited by Mary Russell Mitford. Engraved by William and Edward Finden. 1838.

Read more in this series of blog posts about the exhibit “‘Puppy Love’: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships“:

- Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships in the ABL’s Archive (March 16, 2022)

- Victorian Print Culture and Pet Care (May 18, 2022)

- Reception of E.B. Browning’s and Virginia Woolf’s Dog Writing (June 15, 2022)

- “Puppy Love”: What I Learned Through the Process (July 13, 2022)

- “Puppy Love” Closing Announcement (August 3, 2022)