Julia Margaret Cameron

and Her Children Charles and Henry (1859)

Photograph taken by Lewis CarrollTherefore it is with effort I restrain the overflow of my heart and simply state that my first [camera and] lens was given to me by my cherished departed daughter and her husband, with the word, “It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater.”

The gift from those I loved so tenderly added more and more impulse to my deeply seated love of the beautiful and from the first moment I handled my lens with a tender ardour, and it has become to me as a living thing, with voice and memory and creative vigour…. I longed to arrest all beauty that came before me….

I turned my coal-house into my dark room, and a glazed fowl house I had given to my children became my glass house! The hens were liberated, I hope and believe not eaten. The profit of my boys upon new laid eggs was stopped, and all hands and hearts sympathised in my new labour, since the society of hens and chickens was soon changed for that of poets, prophets, painters and lovely maidens, who all in turn have immortalized the humble little farm erection.

When I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavored to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man. The photograph thus taken has been almost the embodiment of a prayer.

Julia Margaret Cameron

Annals of my Glass House (1874)

Julia Margaret Cameron was born in Calcutta, India. She met her husband, Charles Cameron, on a trip to southern Africa. After her husband’s retirement in 1848, the family moved from India back to England. She took up photography in 1863, at the age of 48, when she was living next door to Alfred Tennyson on the Isle of Wight. She produced photographs for only ten years, but her photographic subjects included Robert Browning, Tennyson, William Makepeace Thackeray, John Ruskin, Thomas Carlyle, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, James Abbott McNeil Whistler, and G. F. Watts. Most of her photographs have a soft, ethereal quality to them.

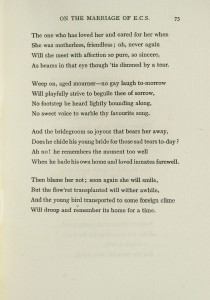

For the exhibition poster for Giving Nineteenth Century Women Writers a Voice and a Face, I chose a quotation from an untitled, unfinished poem found in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s pocket notebook, dated 1842-1844, and a photograph taken by Julia Margaret Cameron in 1864. The contemporaneity of the poem and the photo echo the timelessness of the nineteenth century women’s voices featured in the exhibit.

The subject of the photograph was sixteen-year-old Ellen Terry, a young Shakespearean actress and close friend of Cameron. Ellen had become acquainted with George Frederick Watts, a famous Victorian painter, forty years her senior, when she sat for him for a painting. At the urging of friends, they were married in February 1864. The photo was probably taken during their honeymoon on the Isle of Wight. The couple separated within a year and were formally divorced in 1877. At some later date Cameron titled the photo “Sadness.”

The ABL owns eight original photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron, many with inscriptions. A letter from Robert Browning to Julia Margaret Cameron (24 July 1866) thanking her for her generous gift of photographs is also a part of the collection. Sarianna Browning, sister of Robert Browning in a letter to Joseph Milsand (27 December 1866), records another generous Christmas gift of twelve photographs from Mrs. Cameron.

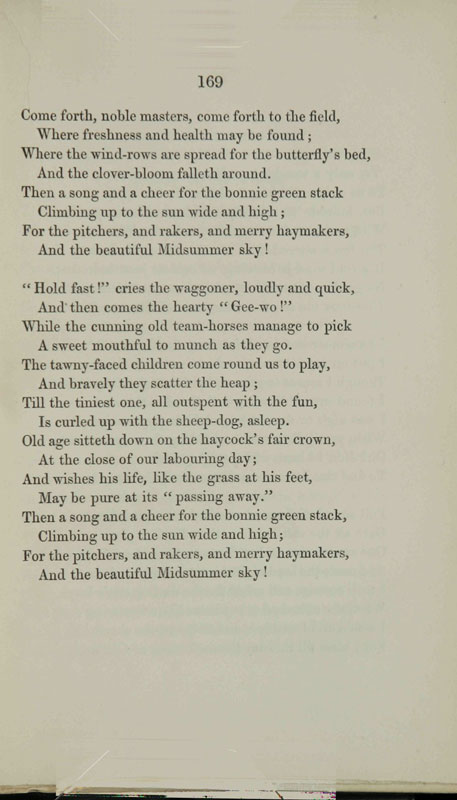

Although Mrs. Cameron turned, quite successfully, to photography later in life, her first love was literature. She wrote an autobiography, translated German, and published poems and fiction. This poem was written shortly before she and her husband left England for Ceylon.

Julia Margaret Cameron

“On a Portrait”

Macmillan Magazine (February 1876)

Notes and Queries: There is an engraving of Joseph Milsand by F. Johnson in Records of Tennyson, Ruskin, and Browning by Anne Thackeray Ritchie. The caption under the engraving reads: “Mr. Milsand / from a copyrighted photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron.” The Armstrong Browning Library has a large Joseph Milsand Collection. A letter from Joseph Milsand to Philbert Milsand (23 May [1874]) indicates that Joseph Milsand was to spend a day on Isle of Wight where Miss Thackeray would introduce him to Tennyson. Another letter from Joseph Milsand to Claire Milsand (11 Feb 1884) talks about Cameron’s beautiful photo of the tall, angel-like white lady which is displayed in his house. Does anyone know the whereabouts of either of the photographs, Milsand’s photographic portrait or the “angel-like white lady” photograph that he owned?