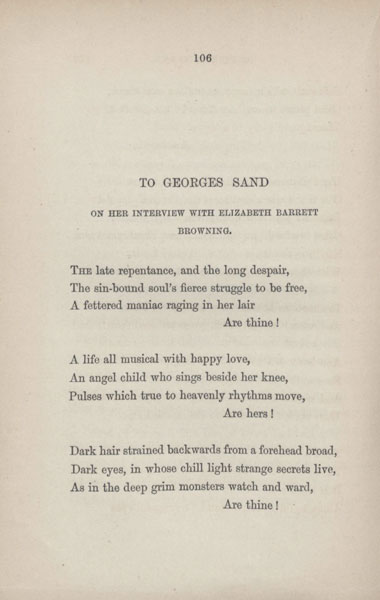

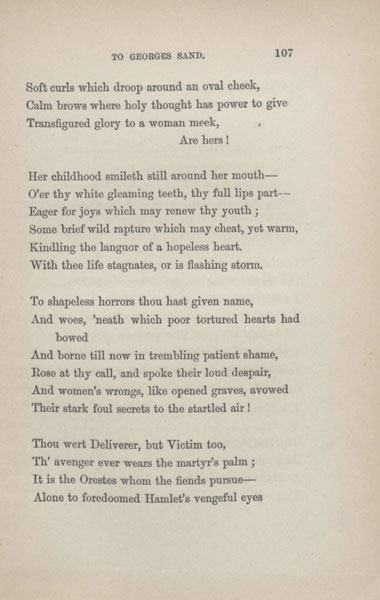

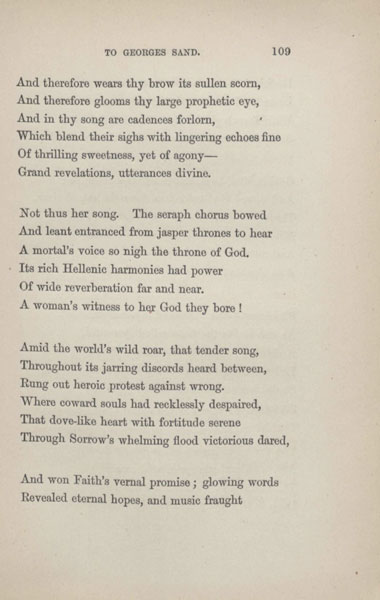

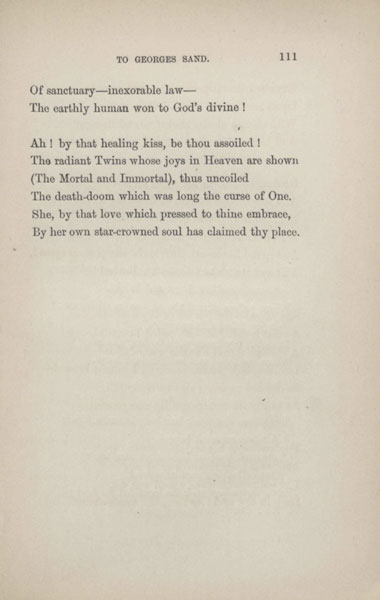

Letters of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning at Wellesley College

In 2012, Wellesley College graciously collaborated with Baylor University in allowing the love letters between Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning housed in Wellesley’s special collections to be digitized and made freely available for viewing on The Browning Letters page of the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections site. In evidence of their continuing partnership and commitment to make the compelling story of the two poets available to scholars and enthusiasts around the globe, this fall eighteen boxes (1,050 letters) traveled to Baylor University from Wellesley College in Massachusetts to be added to The Browning Letters digitization project. A selection of these letters is presented here in celebration and appreciation of the Armstrong Browning Library’s donors and supporters.

The letters on display from Elizabeth Barrett Browning are to some of her most frequent correspondents and intimate friends. Among the recipients are scholar Hugh Stuart Boyd, artist and writer Benjamin Robert Haydon, cousin John Kenyon, writer Mary Russell Mitford, art critic and writer Anna Brownell Jameson, and family friend Julia Martin. In the letters, Elizabeth shares the joy she feels after becoming the wife of Robert and the mother of a healthy baby boy. She dramatically recounts an incident in which her pet Spaniel Flush was dognapped and recovered. She also reveals the pain she experienced when her close friend Mary Russell Mitford betrayed her trust and when her father’s death ended the possibility of reconciliation with him.

The letters on display from Robert Browning to John Kenyon and Julia Martin provide further insight into Elizabeth’s dispute with Mary Russell Mitford and her estrangement from her father. In a letter to William Cornwallis Cartwright, a friend and former Member of Parliament in London, Robert recalls the engagement and marriage of his son Pen. Also included is a letter from John Ruskin, leading art critic of the nineteenth century, to Robert praising Elizabeth’s Aurora Leigh as the greatest poem in the English language.

§

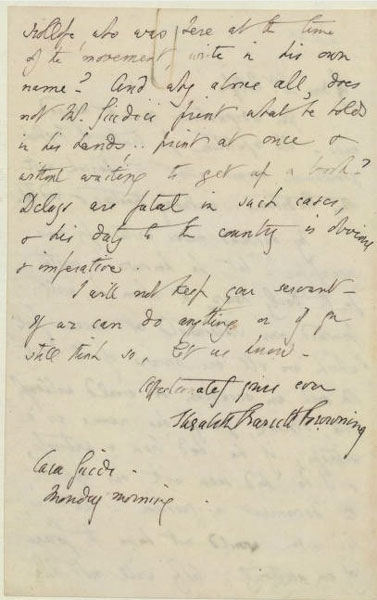

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett to Hugh Stuart Boyd.

28 [-29] May 1828.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Hugh Stuart Boyd (1781-1848) was a scholar with whom EBB shared a passion for Greek literature. He was also an admirer of her poetry.

In this letter, EBB thanks Mr. Boyd for reading The Battle of Marathon, a poem she wrote at a very young age.

I am at once sorry & pleased that you should have actually read thro’ the little book which forms the subject of your letter—sorry, to have inflicted such dulness on you,—& pleased, to receive such a proof of your friendship.

§

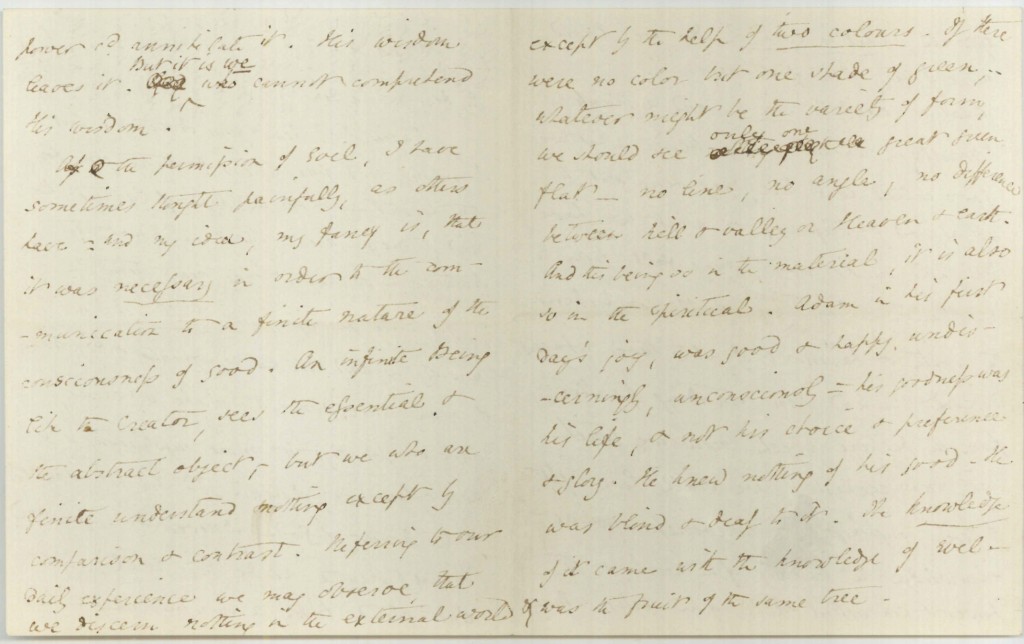

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett to Benjamin Robert Haydon.

29 November 1842.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

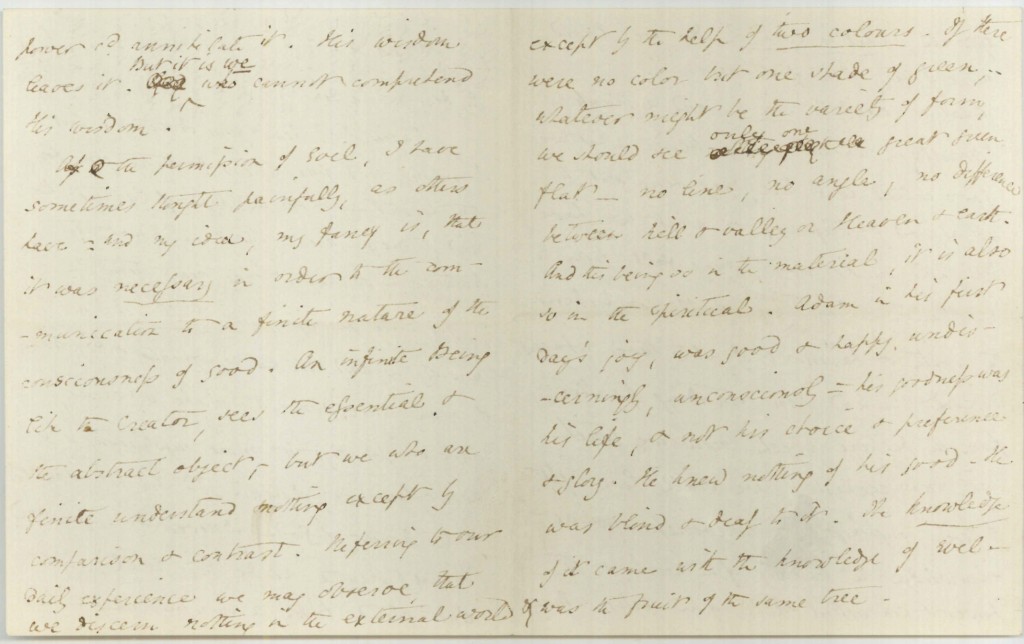

Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786-1846), an artist and writer, and EBB became acquainted in 1841 through their mutual friend Mary Russell Mitford. The pair corresponded frequently “by little notes on great subjects,” EBB wrote to Miss Mitford on 6 December 1842.

One example follows:

An infinite Being like the Creator, sees the essential & the abstract object; but we who are finite understand nothing except by comparison & contrast. Referring to our daily experience we may observe, that we discern nothing in the external world except by the help of two colours. If there were no color but one shade of green, .. whatever might be the variety of form, we should see only one great green flat—no line, no angle, no difference between hill & valley or Heaven & earth. And this being so in the material, it is also so in the spiritual. Adam in his first day’s joy, was good & happy, undiscerningly, unconsciously: his goodness was his life, & not his choice & preference & glory. He knew nothing of his good. He was blind & deaf to it. The knowledge of it came with the knowledge of Evil—& was the fruit of the same tree. After all, what is evil? Do we know more of that, than of its origin?

§

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett to John Kenyon. 19 May 1843.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

John Kenyon (1784-1856) was a distant cousin of EBB’s and a mutual family friend of EBB and RB. He was responsible for bringing the two poets together.

In this letter, EBB thanks Mr. Kenyon for sending her a letter from RB in which he praises her poem “The Dead Pan.”

And then Mr Browning’s note! Unless you say ‘nay’ to me, I shall keep this note which has pleased me so much—yet not more than it ought– Now I forgive Mr Merivale for his hard thoughts of my easy rhymes.– But all this pleasure my dear Mr Kenyon, I owe to you, & shall remember that I do–

§

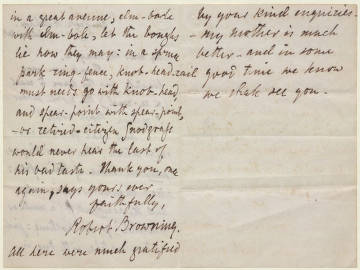

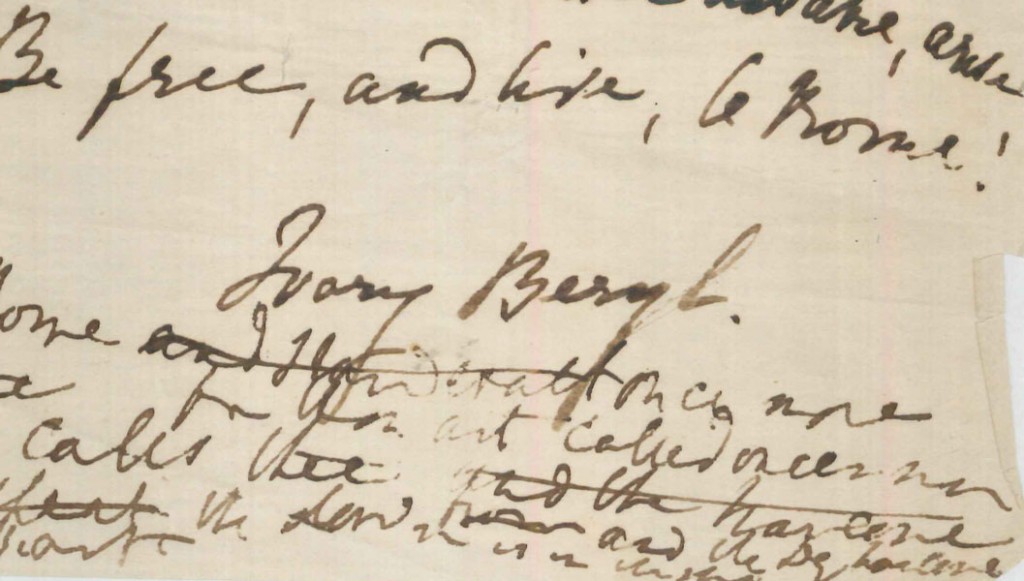

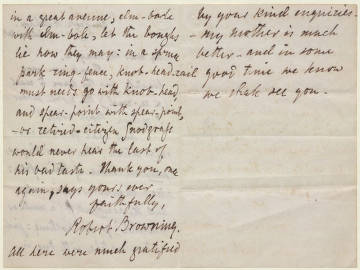

Courtesy of Armstrong Browning Library

RB’s letter to Mr. Kenyon about EBB’s poem “The Dead Pan” is housed at the Armstrong Browning Library. It is here reunited with EBB’s letter to John Kenyon housed at Wellesley College.

Thank you very heartily for the leave to read (& re-read) the noble verses I return. Most noble!

And what famous versification! The grand rhymes pair in virtue of their essential characteristics only, and the accidents (of a mute or a liquid) go for nothing: just as tree matches with tree in a great avenue, elm-bole with elm-bole, let the boughs lie how they may: in a spruce park ring-fence, knob-head-rail must needs go with knob-head, and spear-point with spear-point,—or retired-citizen Snodgrass would never hear the last of his bad taste.

§

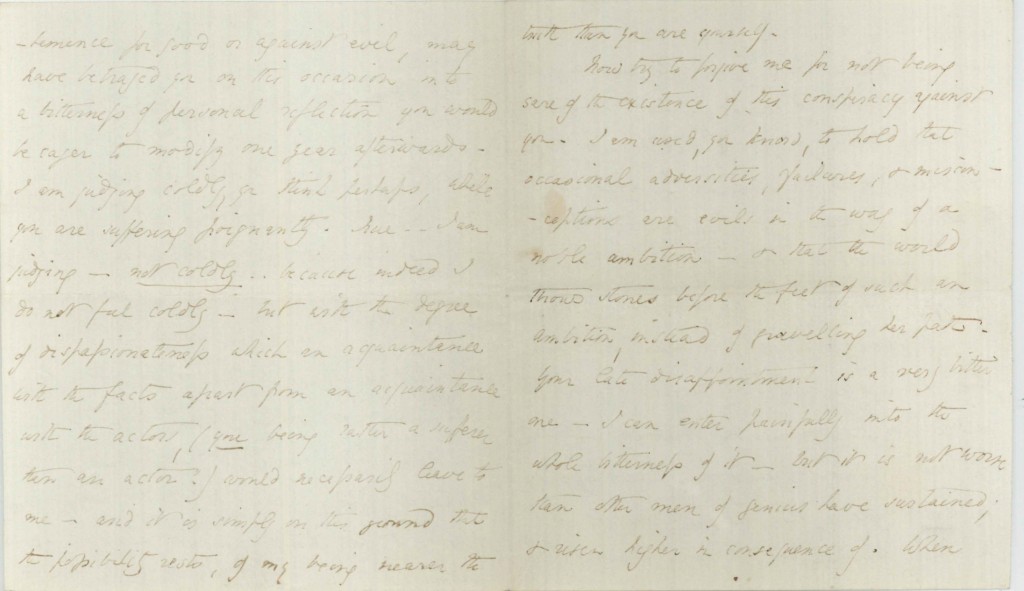

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett to Benjamin Robert Haydon.

19 July 1843.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

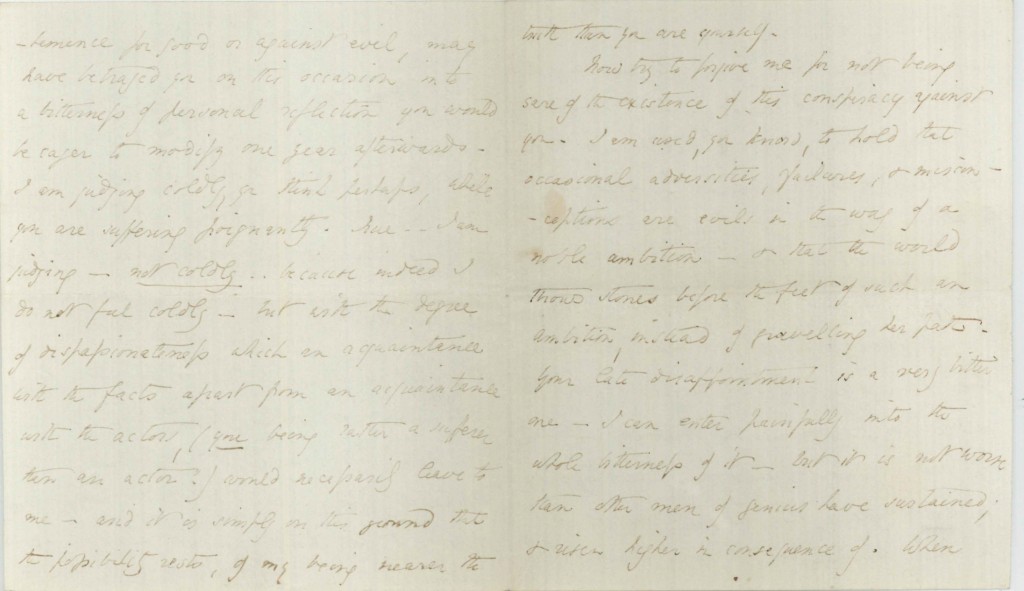

In 1843, Mr. Haydon submitted “cartoons” in a competition to select frescoes for the new Houses of Parliament. Mr. Haydon’s entries were not included among the winners, and he was resentful of the loss. Of his reaction to the outcome, EBB writes to Mr. Haydon:

Now try to forgive me for not being sure of the existence of this conspiracy against you– I am used, you know, to hold that occasional adversities, failures, & misconceptions are evils in the way of a noble ambition—& that the world throws stones before the feet of such an Ambition, instead of gravelling her path. Your late disappointment is a very bitter one—I can enter painfully into the whole bitterness of it—but it is not worse than other men of genius have sustained, & risen higher in consequence of. When Corinna took the crown from over Pindar’s head, all Greece looking on, he was mortified & grieved of course—but he did not upbraid his judges with treachery: and who speaks now of Corinna? Wordsworth, all the reviewers & three quarters of the public laughed to scorn, as an inarticulate idiot; but he upbraided none of them with conspiracy: and who scorns Wordsworth now?

§

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett to Mary Russell Mitford.

16 September 1843.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Mary Russell Mitford (1787-1855) was a well-known writer and was introduced to EBB by John Kenyon in 1836. EBB corresponded with Miss Mitford for nearly two decades and wrote more letters to her than to any other person.

In this letter, EBB dramatically recounts the dognapping and recovery of her pet Spaniel Flush, a gift from Miss Mitford after the death of her brother “Bro” in 1840.

[The dogstealer] said also with most marvellous coolness, “that they had been for two years on the watch for Flush, & that they had hoped to get hold of him the other day when he was out with the lady in the chair, as he had been several times lately.” Conceive the audacity!—and the hardheartedness!! They must have guessed at my state of health, by the very movement of the chair,—drawn for a few steps & then resting!—and to calculate cooly on such an opportunity of taking away the little dog of which I was obviously so fond!– I said so to my brothers; & they laughed. “Hardheartedness! Why they wd have cut your own throat for five pounds”!– And that is true.

§

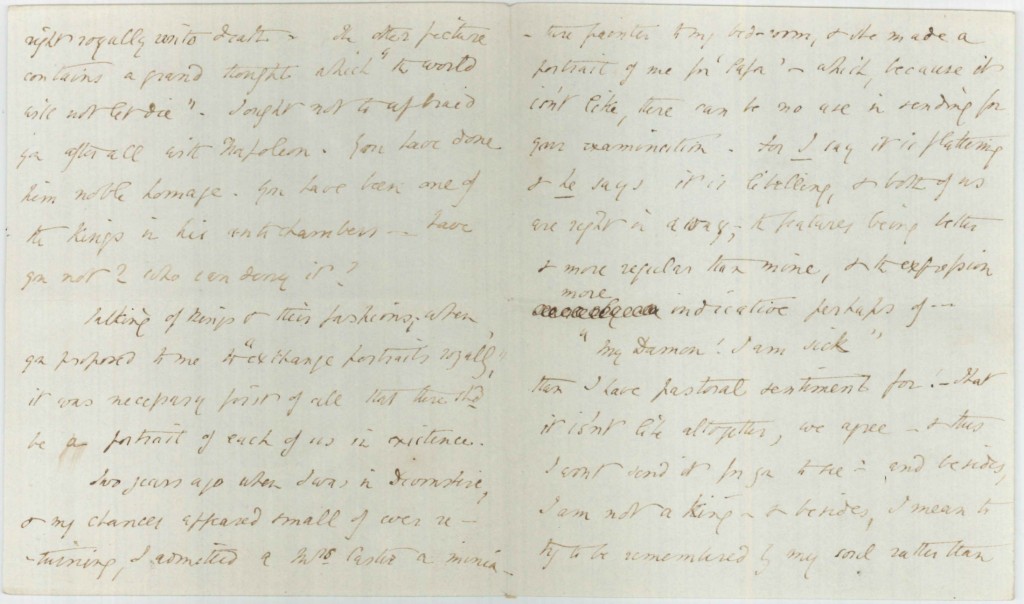

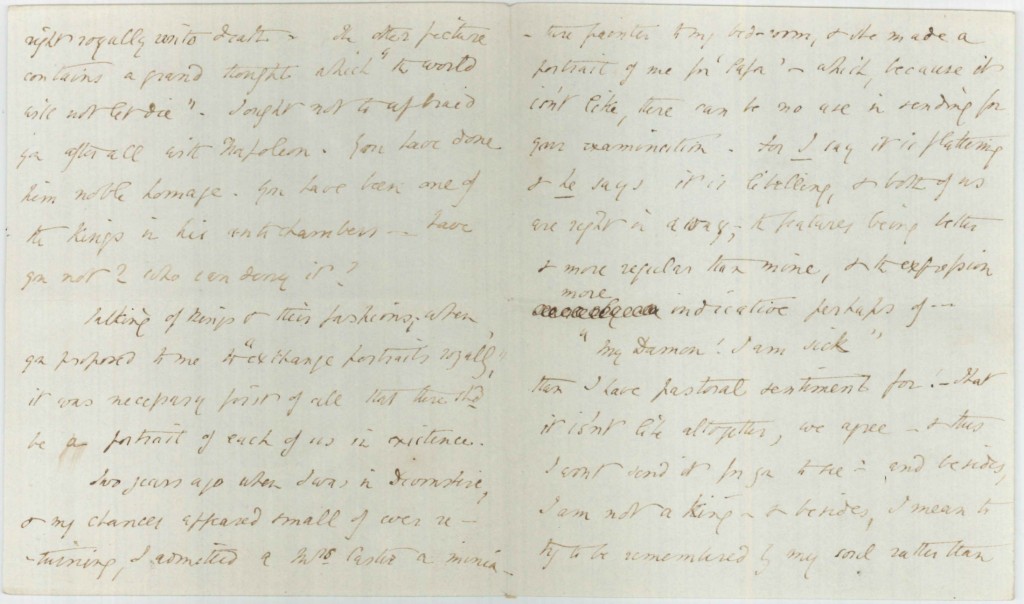

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett to Benjamin Robert Haydon.

1 January 1844.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Although they corresponded with one another for three years, EBB and Mr. Haydon never met in person. In this letter, EBB responds to Mr. Haydon’s request to exchange portraits. Not having a suitable image available, EBB determines to describe herself in prose.

I mean to try to be remembered by my soul rather than by my body […] Yet to give scanty data to your fancy,—thus,—I am “little & black” like Sappho, en attendant the immortality—five feet one high,—with the latitudes straight to correspond—eyes of various colours as the sun shines— .. called blue & black, without being accidentally black & blue—affidavit-ed for grey—sworn at for hazel—& set down by myself (according to my ‘private view’ in the glass) as dark-green-brown—grounded with brown; & green otherwise; what is called “invisible green” in invisible garden-fences .. I shd be particular to you who are a colourist. Not much nose of any kind, .. certes no superfluity of nose; but to make up for it, a mouth suitable to a larger personality—oh, and a very very little voice, to which Cordelia’s was a happy medium. Dark hair & complexion. Small face & sundries.

§

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett to Hugh Stuart Boyd.

[Early July 1846].

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

EBB hints at her plans to marry RB:

From my heart I may say to you, that, looking back to that early time, the hours spent with you, appear to me some of the happiest of my life .. a life in which the “happiest part has not prevailed,” as is the chorus of Agamemnon. A prophet said to me (by his way) a week since, that God intended me compensation, even in the world, & that the latter time would be better for me than the beginning.

Mr. Boyd was supportive of RB and EBB’s marriage, and his home was the first place EBB visited after the secret marriage ceremony on 12 September 1846.

§

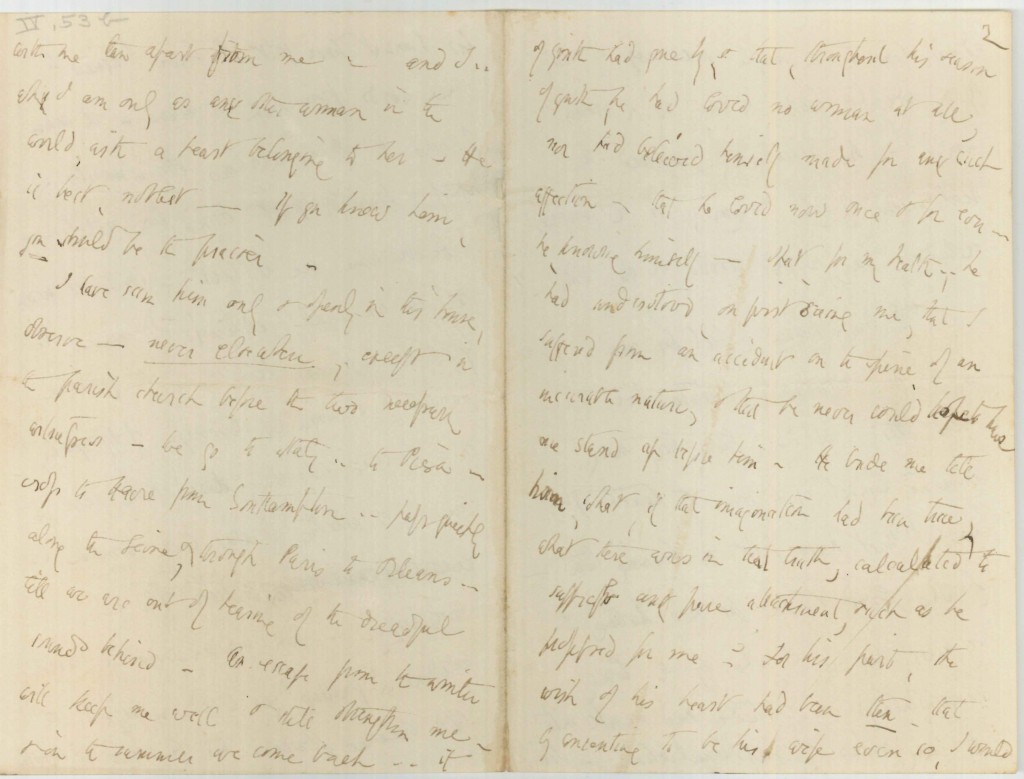

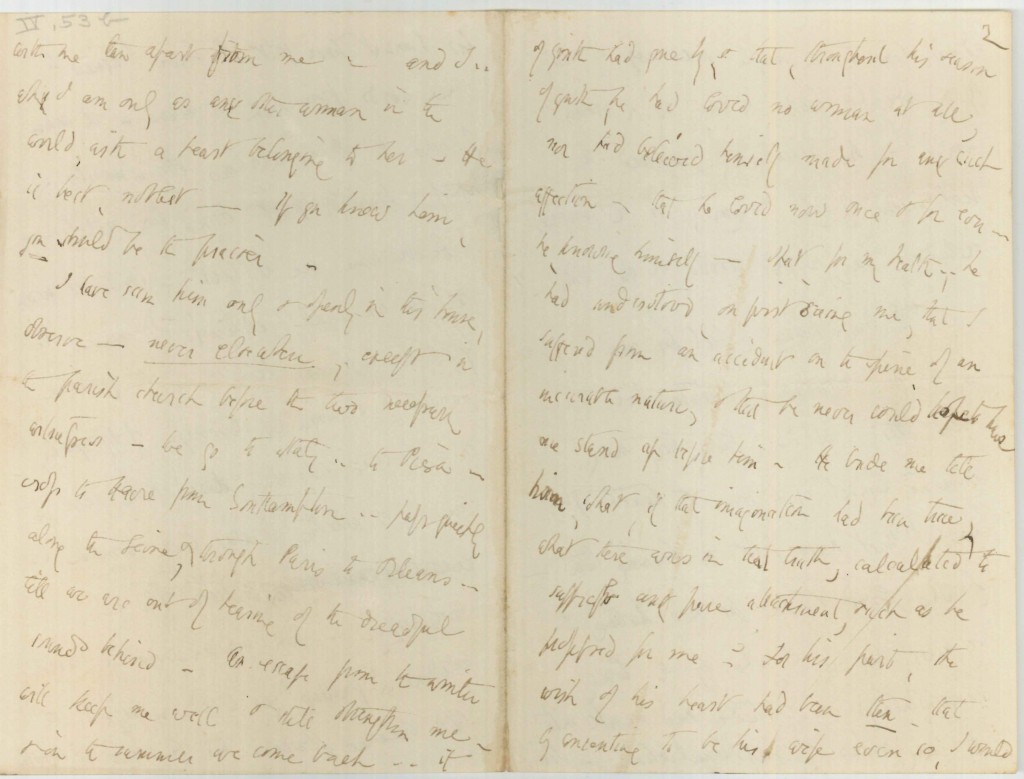

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford.

[18 September 1846].

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

EBB reveals in this letter to Miss Mitford that she has married RB. Miss Mitford did not think favorably of RB, writing of her first impressions of the poet to Charles Boner on [22 February 1847]: “I saw Mr Browning once & remember thinking how exactly he resembled a girl drest in boy’s clothes.” She described his poetry in the same letter as “one heap of obscurity confusion & weakness.”

EBB writes to Miss Mitford:

… when you read this letter I shall have given to one of the most gifted & admirable of men, a wife unworthy of him. I shall be the wife of Robert Browning. Against you, .. in allowing you no confidence, .. I have not certainly sinned, I think—so do not look at me with those reproachful eyes. I have made no confidence to any .. not even to my & his beloved friend Mr Kenyon—& this advisedly, & in order to spare him the anxiety & the responsibility. It would have been a wrong against him & against you to have told either of you—we were in peculiar circumstances—& to have made you a party, would have exposed you to the whole dreary rain—without the shelter we had– If I had loved you less—dearest Miss Mitford, I could have told you sooner.

…..

How can I tell you on this paper, even if my hands did not tremble as the writing shows, how he persisted & overcame me with such letters, & such words, that you might tread on me like a stone if I had not given myself to him, heart & soul. When I bade him see that I was bruised & broken .. unfit for active duties, incapable of common pleasures .. that I had lost even the usual advantages of youth & good spirits—his answer was, “that with himself also the early freshness of youth had gone by, & that, throughout his season of youth, he had loved no woman at all, nor had believed himself made for any such affection—that he loved now once & for ever

…..

Think how I must have felt to have listened to such words from such a man. A man of genius & of miraculous attainments .. but of a heart & spirit beyond them all!——

…..

the truth became obvious that he would be happier with me than apart from me—and I .. why I am only as any other woman in the world, with a heart belonging to her. He is best, noblest—— If you knew him, you should be the praiser.

§

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Anna Brownell Jameson.

30 April [1849].

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Anna Brownell Jameson (1794-1860) was an art critic and writer and a mutual friend of RB and EBB before their courtship and marriage. She traveled to Italy with the Brownings shortly after their marriage and remained a close friend of EBB’s until her death in 1860.

In this letter, EBB delights at the health of her son Robert Wiedeman Barrett Browning, later known as “Pen,” who was born on 9 March 1849 when EBB was forty-three.

Dearest friend, if you could see him at this moment you would wonder how such a child could be my child, .. just as I wonder myself. Such large round cheeks, such a superfluity of chins, such a broad chest, and vigorous legs & arms—and really a beautiful child too—called “a model for Michal Angelo” by the accoucheur and “un Jesu bambino” by the monthly nurse, the wet nurse being of opinion that “the Signora must have seen some very pretty people when she walked out in the streets!”– What has been curiously beautiful from the beginning is his complexion– No “red gum” nor rashes of any kind, nor weak eyes, nor other common scourges of early babyhood– Now his two cheeks have roses in them, one on each side. And such a good baby! So serene & unfretful! Robert walks with him in his arms up & down the terrace, & I could’nt if I tried ever so, the weight is so great.

§

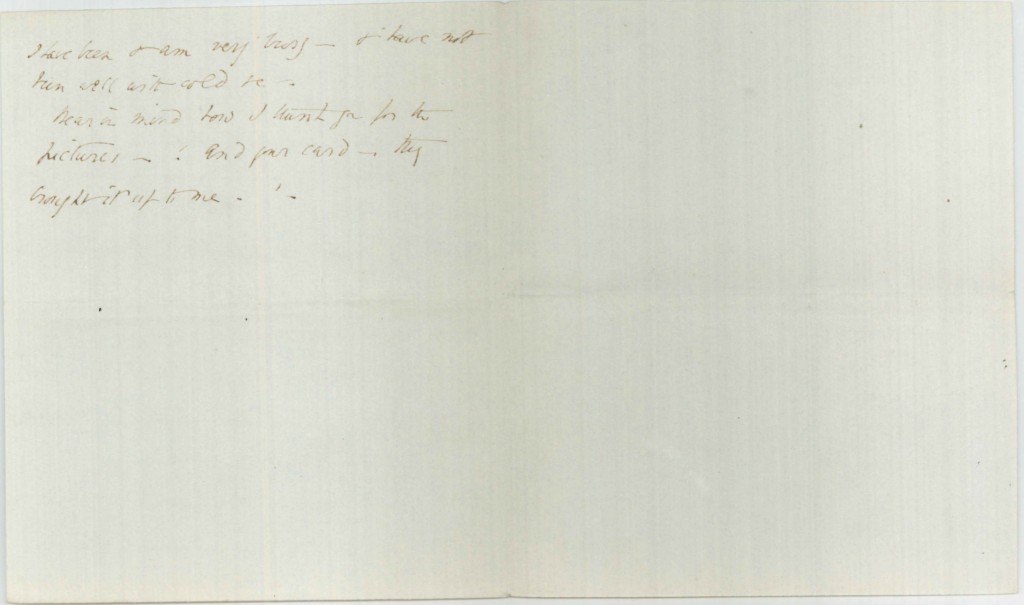

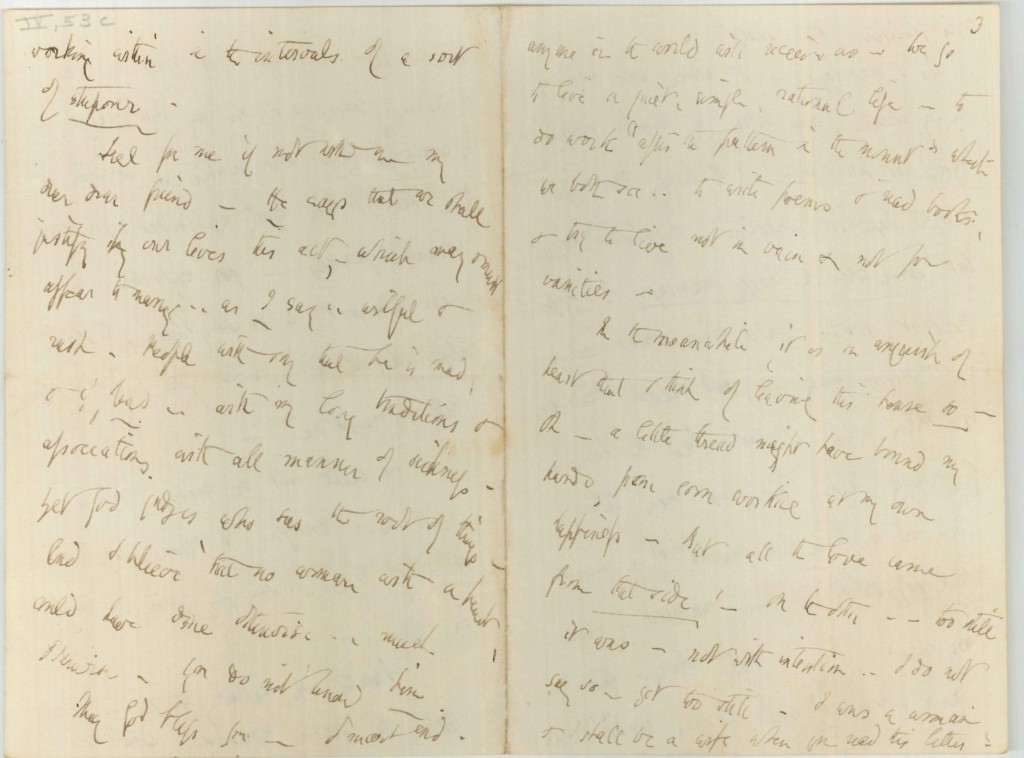

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Julia Martin. [17 September 1851].

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Julia Martin (1792-1866) was a neighbor of the Moulton-Barrett family when they lived at Hope End, their large estate in Herefordshire. Supportive of EBB’s marriage to RB, Mrs. Martin encouraged the reconciliation of Edward Moulton-Barrett and his daughter after her elopement with RB.

In this letter to Mrs. Martin, EBB describes her father’s refusal to see her during a trip to England.

For the rest, the pleasantness is not on every side. It seemed to me right, notwithstanding that dear Mr Kenyon advised against it, to apprize my father of my being in England. I could not leave England without trying the possibility of his seeing me once .. of his consenting to kiss my child once. So I wrote—and Robert wrote– A manly, true, straightforward letter his was, yet in some parts so touching to me, & so generous & conciliating everywhere, that I could scarcely believe in the probability of its being read in vain. In reply he had a very violent & unsparing letter, .. with all the letters I had written to Papa through these five years, sent back unopened .. the seals unbroken. What went most to my heart was, that some of the seals were black, with black-edged envelopes,—so that he might have thought my child or husband dead, yet never cared to solve the doubt by breaking the seal. He said, he regretted to have been forced to keep them by him until now, through his ignorance of where he should send them. So, there’s the end. I cannot of course write again. God takes it all into His own Hands, & I wait.

§

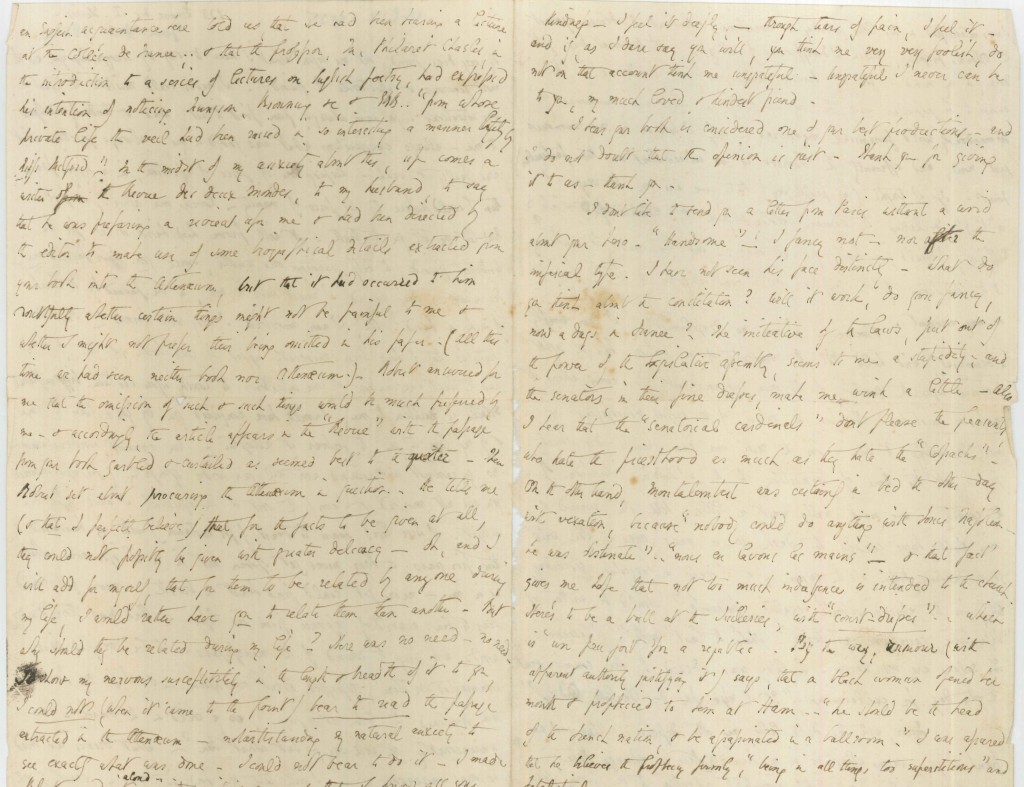

Letter from Robert Browning to John Kenyon. 14 January 1852.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

EBB and Mary Russell Mitford’s friendship was tested in 1852 when Miss Mitford published an account of the tragic drowning death of EBB’s brother “Bro” in her book Recollections of a Literary Life.

RB writes of the indiscretion to Mr. Kenyon:

I was informed last week, by a lady-friend, that Mr. Philarète Chasles, one of the Professors at the College de France, had mentioned in his lecture (on “Literature derived from Germanic sources,” or some such title[)], that in the course of his labours he should need to treat of such & such English Poets, and of “their greatest poetess, E.B.B, from whose life such a veil had just been raised by Miss Mitford”—with much flourish that I omit. We knew Miss M. had been bookmaking, criticising &c—but had no notion she could be so silly & thoughtless as to leave that legitimate business for a notice of anybody’s private life, least of all, Ba’s—whose acute, even morbid feeling on the subject she well knows.

§

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford.

[21-22 January 1852].

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

EBB writes of the distress Miss Mitford has caused her by making the painful memory of her brother’s death public knowledge in Recollections of a Literary Life:

My very dear friend, Let me begin what I have to say by recognizing you as the most generous & affectionate of friends. I never could mistake the least of your intentions: you were always, from first to last, kind & tenderly indulgent to me—always exaggerating what was good in me, always forgetting what was faulty & weak—keeping me by force of affection, in a higher place than I could aspire to by force of vanity—loving me always, in fact. Now let me tell you the truth. It will prove how hard it is for the tenderest friends to help paining one another, since you have pained me. See what a deep wound I must have in me, to be pained by the touch of such a hand … But the truth is that I have been miserably upset by your book, & that if I had had the least imagination of your intending to touch upon certain biographical details in relation to me, I would have conjured you by your love to me & by my love to you to forbear it altogether.

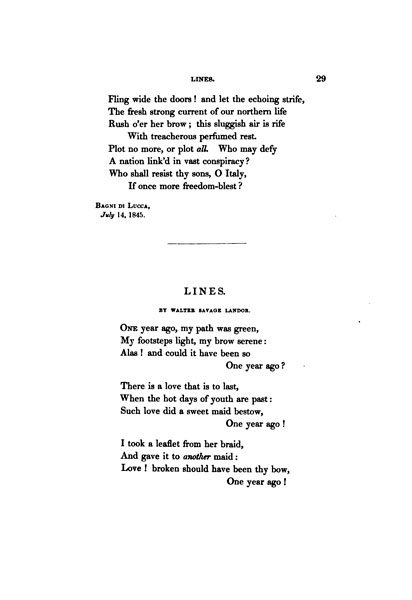

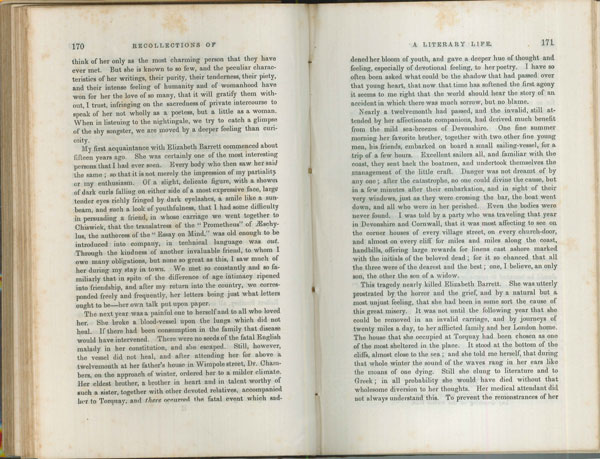

Mary Russell Mitford. Recollections of a Literary Life; or, Books, Places and People. New York: Harper, 1852.

The passage that so offended EBB begins at the bottom of page 170.

The passage that so offended EBB begins at the bottom of page 170.

§

§

Letter from John Ruskin to Robert Browning. 27 November 1856.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

In this letter to RB, John Ruskin (1819-1900), the leading art critic of the 19th century, praises EBB’s Aurora Leigh:

I think Aurora Leigh the greatest poem in the English language: unsurpassed by anything but Shakespeare—not surpassed by Shakespeares sonnets—& therefore the greatest poem in the language. I write this, you see, very deliberately, straight, or nearly so, which is not common with me, for I am taking pains that you may not think—(nor anybody else) that I am writing in a state of excitement, though there is enough in the poem to put one into such a state.

§

Letter from Robert Browning to Julia Martin. 3 May 1857.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

RB reflects on the death of EBB’s father on 17 April 1857:

So it is all over now, all hope of better things, or a kind answer to entreaties such as I have seen Ba write in the bitterness of her heart. There must have been something in the organisation, or education, at least, that would account for and extenuate all this; but it has caused grief enough, I know; and now here is a new grief not likely to subside very soon. Not that Ba is other than reasonable and just to herself in the matter: she does not reproach herself at all; it is all mere grief, as I say, that this should have been so; and I sympathise with her there.

§

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Julia Martin. 1 July [1857].

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

EBB writes of her estrangement from her father:

I believe hope had died in me long ago of reconciliation in this world. Strange, that what I called ‘unkindness’ for so many years, in departing should have left to me such a sudden desolation! And yet, it is not strange, perhaps.

§

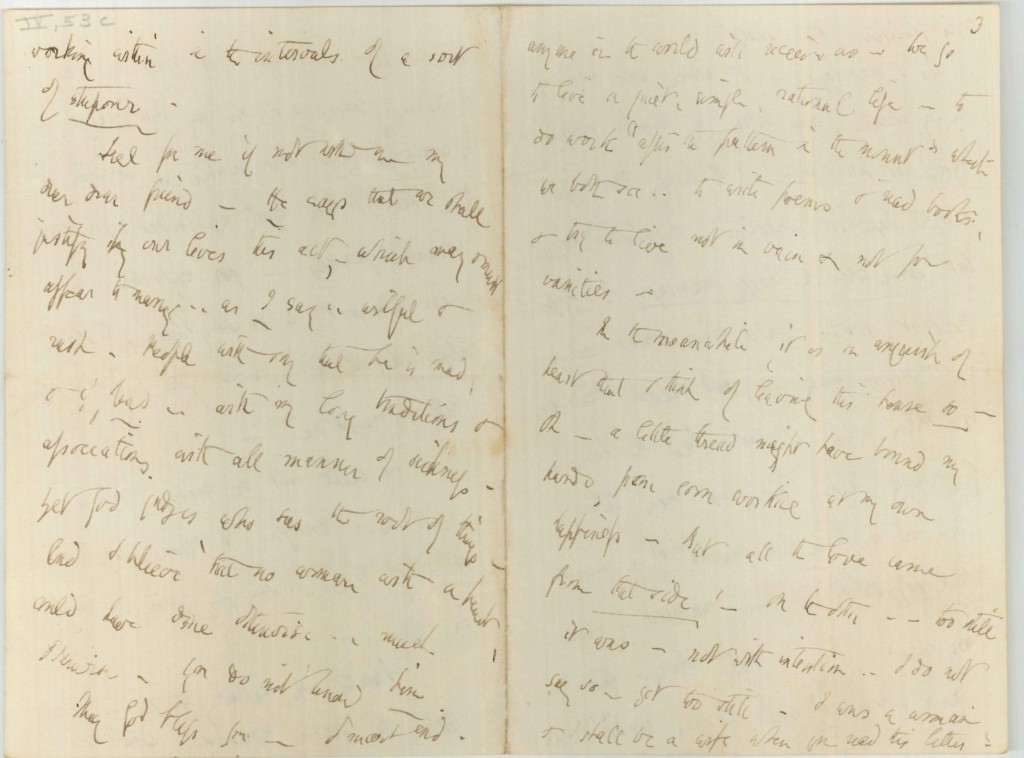

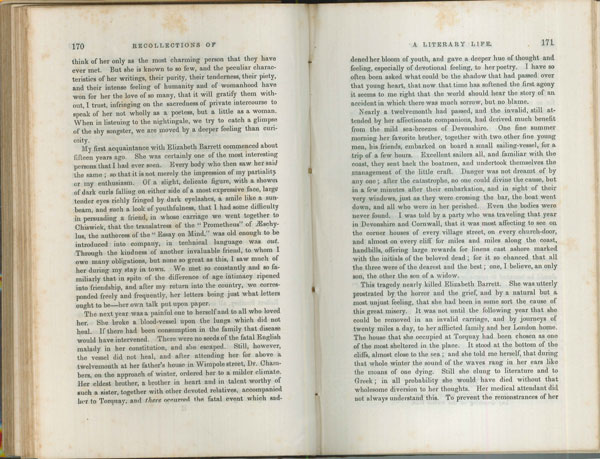

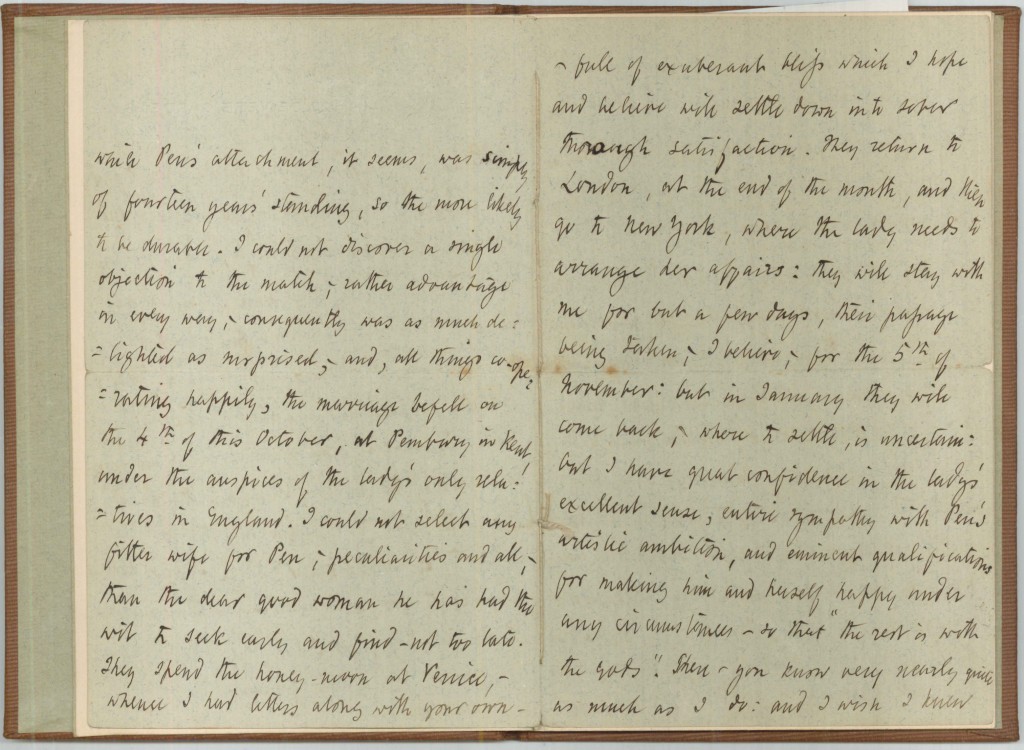

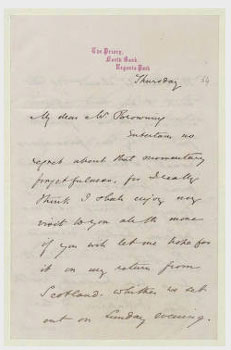

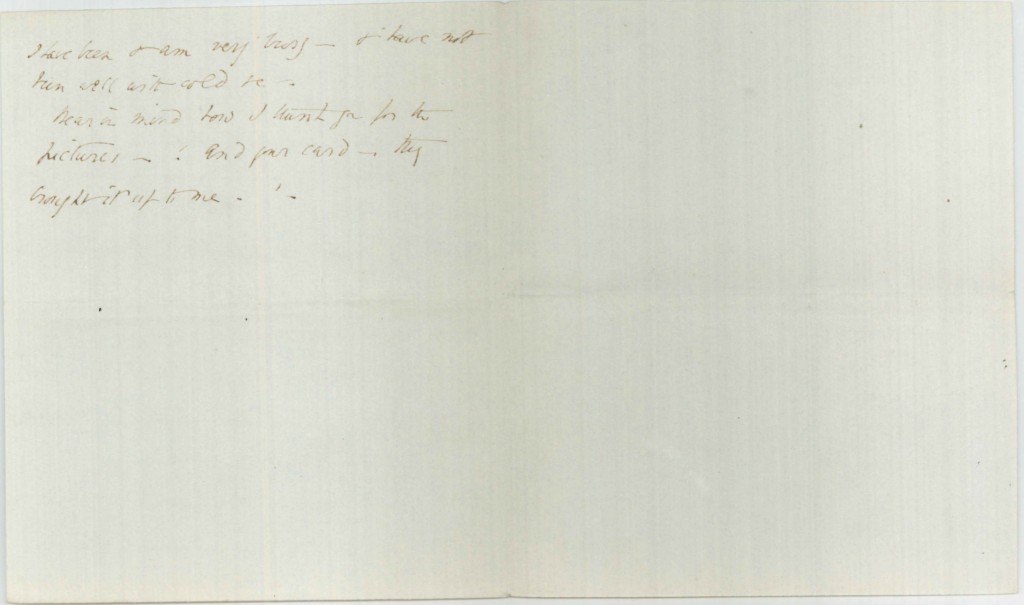

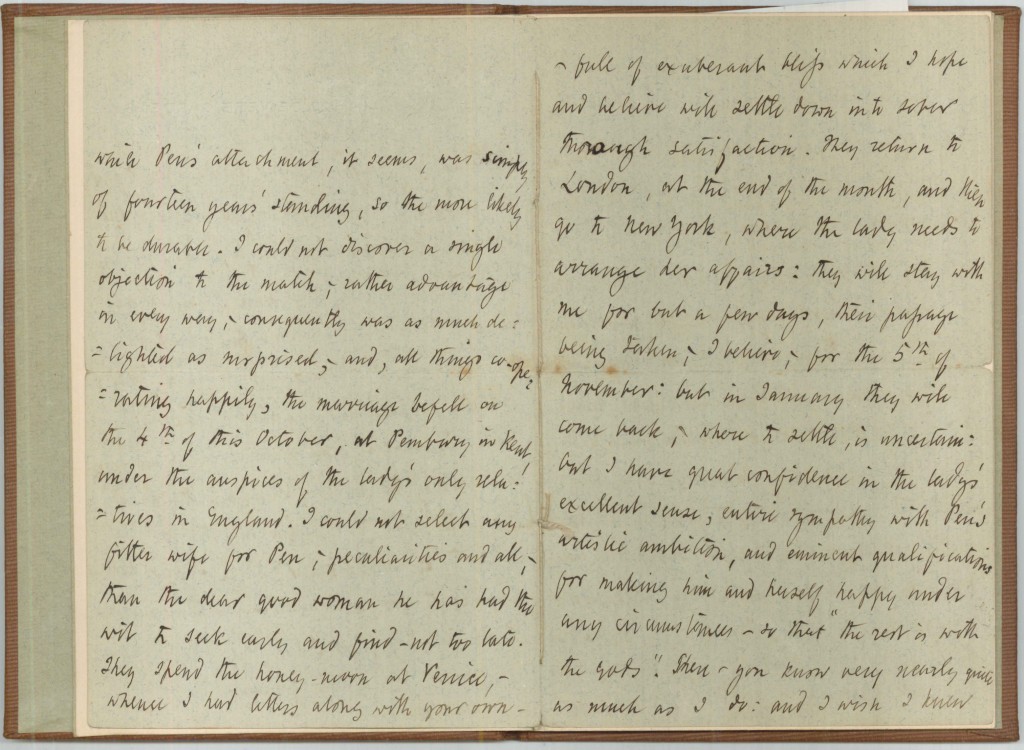

Letter from Robert Browning to William Cornwallis Cartwright. 16 October 1887.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

Courtesy of Wellesley College Library, Special Collections

In this letter to his friend William Cornwallis Cartwright (1825-1915), a former Member of Parliament in London, RB recounts the engagement and marriage of his son Pen to American Fannie Coddington:

My dear Cartwright,—had I known where to find you, be sure I would have written long ago and told you all about Pen’s engagement. Yet “long ago” is not so very long, since I only became aware of Pen’s wishes about two months ago—I being at St Moritz and he at Dinant: but the proposal and acceptance had taken place in London some weeks before,—unaware as I was of the matter,—whereupon the parties separated, Pen to Belgium, and the lady and her sister to Swizterland,—where I was duly applied to for my consent—which was given most heartily, for I had long been acquainted with the lady’s family—a most estimable one: while Pen’s attachment, it seems, was simply of fourteen years’ standing, so the more likely to be durable. I could not discover a single objection to the match,—rather advantage in every way,—consequently was as much delighted as surprised,—and, all things co-operating happily, the marriage befell on the 4th of this October, at Pembury in Kent, under the auspices of the lady’s only relatives in England. I could not select any fitter wife for Pen,—peculiarities and all,—than the dear good woman he has had the wit to seek early and find—not too late.