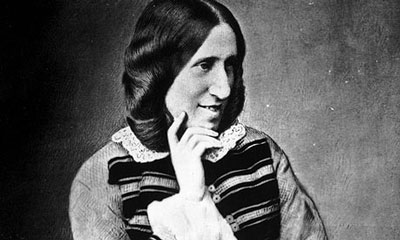

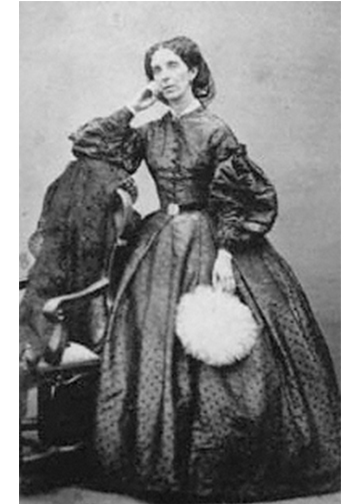

Jean Ingelow

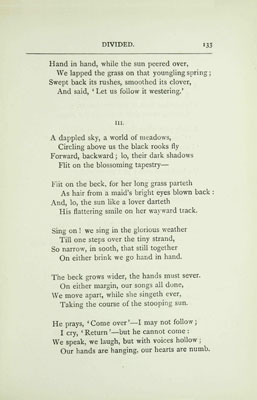

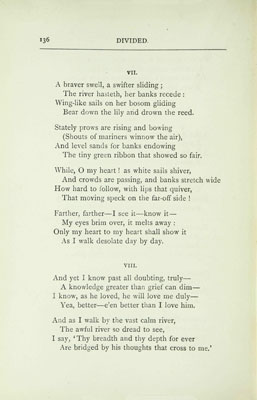

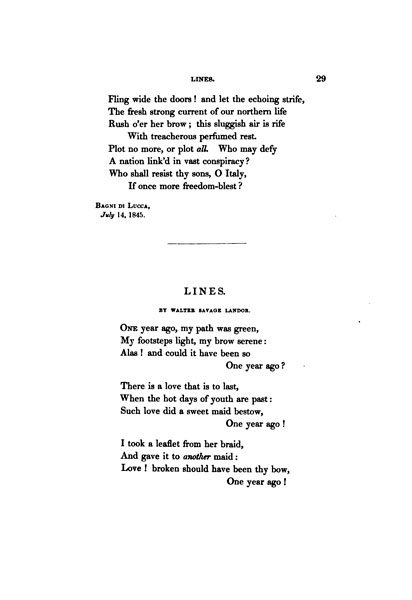

“Divided”

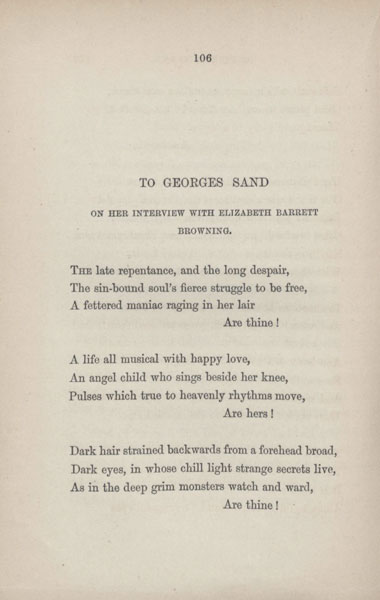

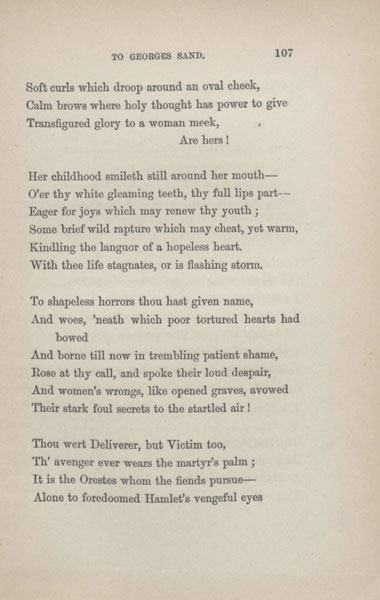

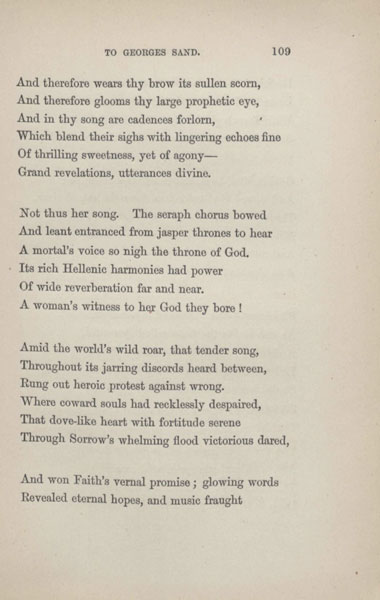

Lyrical and Other Poems

Selected From the Writings of Jean Ingelow (1886)

Courtesy of the Armstrong Browning Library

Jean Ingelow published poetry, a novel which explored the relationship between evangelicals and the traditional Anglicans in the Church of England, and a series of fanciful, didactic stories for children. She is most remembered for her poetry, which is reminiscent of Wordsworth. Dr. Maura Ives, Associate Professor at Texas A & M University and Associate Director of The Initiative for Digital Humanities, Media, and Culture, suggests that “Divided” is one of Ingelow’s most famous poems. The poem is a fascinating description of two lovers walking along hand in hand on opposite sides of a rivulet. They are separated as the rivulet increases to a stream, a river, and an estuary. The lovers call to each other to cross over, but neither does, and they remain divided.

Dr. Ives also reports that her personal favorite is a children’s story “Nineteen Hundred and Seventy Two” in Stories Told to a Child (1872). She discusses the story in “Jean Ingelow in the Youth’s Magazine” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 102.2 (2008): 197-220. Dr. Ives’ research suggests that the story was first printed as “Nineteen Hundred and Fifty-Two” (February 1852) in Youth’s Magazine and signed “E. D.” It was reprinted as “Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Two” in The Little Wonder Horn (1872), in Stories Told to a Child (1872), The Little Wonder Box (1887), and in Good Words for the Young (February 1872).

Ingelow became a bit of a maverick in writing this fantasy story for children. Most of the fantasy literature in the nineteenth century was written by men; women wrote realistic stories of home life and school days. The story, written in 1872, predicts what the world would look like in 1972. She uncannily gives a surprisingly accurate description of the “acoustigraph” twenty-five years before Edison’s invention in 1877.

“…he began to describe what was evidently some great invention in acoustics, which, he said (confusing his century with mine), ‘…you are going to find out very shortly…you know something of the beginnings of photography?’

“I replied that I did.

“‘Photography’ he remarked, ‘presents a visible image; cannot you imagine something analogous to it which might present an audible image? The difference is really that the whole of a photograph is always present to the eye, but the acoustigraph only in successive portions. The song was sung and the symphony played at first and it recorded them, and gave them out in one simultaneous, horrible crash; then when we had once got them fixed science soon managed, as it were, to sketch the image and now we can elongate it as much as we please.’

“‘This is very queer!’ I exclaimed. ‘Do you mean to tell me these notes and those voices are only the ghosts of sounds?’

“‘Not in any other sense,’ he answered, ‘than you might call a photograph a ghost of sight.’

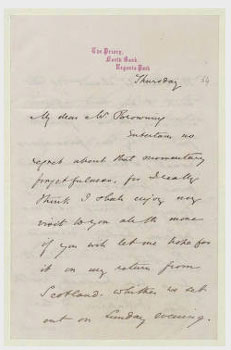

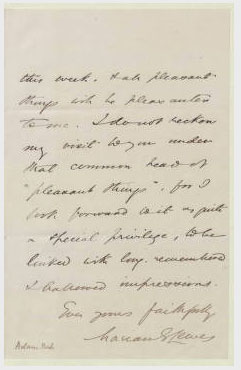

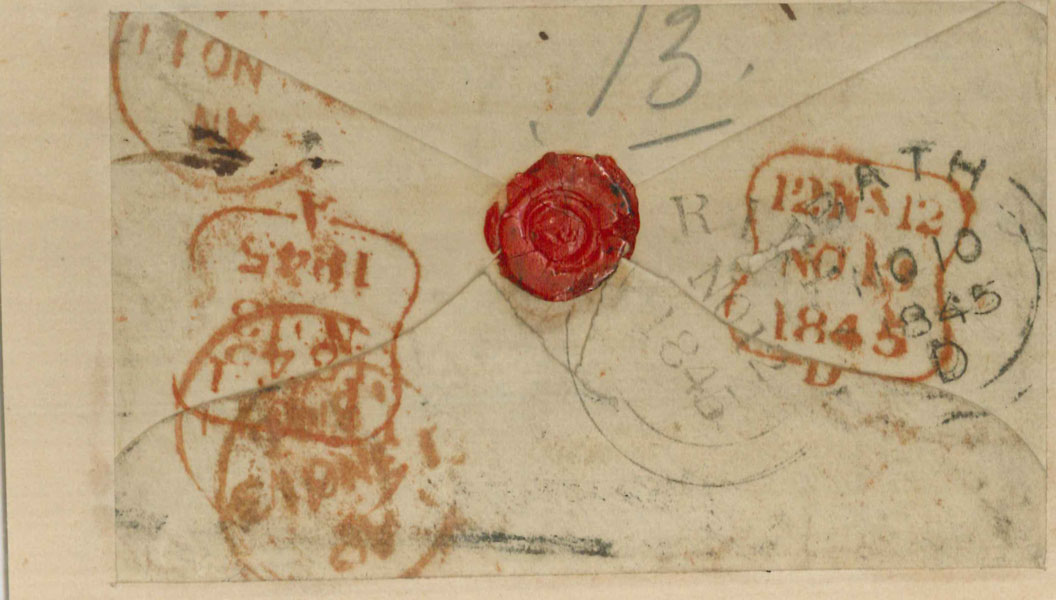

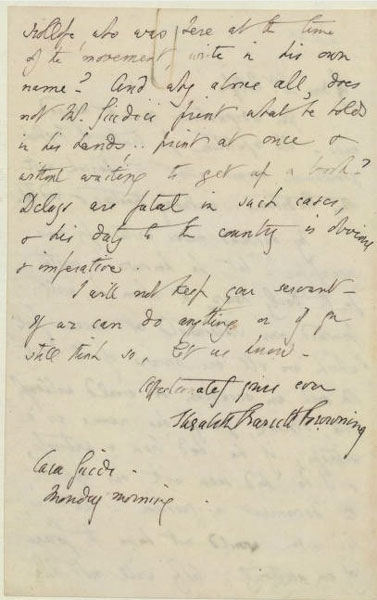

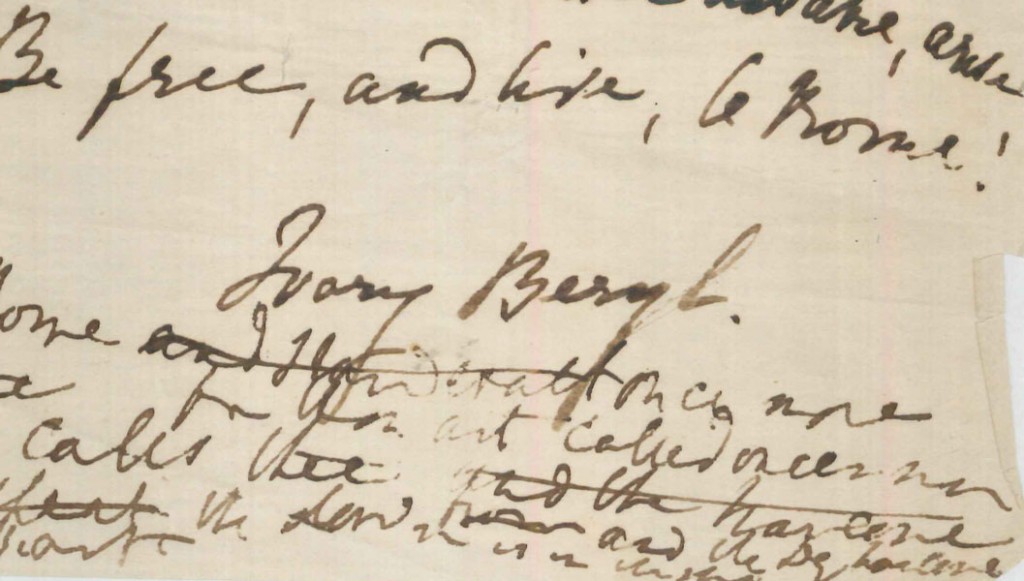

ABL has one letter and six books by Ingelow, one of which, A Story of Doom and Other Poems, 1867, was in the Brownings’ library. The ABL also owns a letter from Jean Ingelow to Robert Browning [23 July [1867]] referring to A Story of Doom and Other Poems. The letter states “I send with this note a little volume of verses which I hope you will do me the favour to accept.”