Each month, we post an update to notify our readers about the latest archival collections to be processed and some highlights of our print material acquisitions. These resources are primed for research and are just a sampling of the many resources to be found at The Texas Collection!Continue Reading

Baptist history

Sharing Student Scholarship: Access at Baylor University, 1900-1910

Our Sharing Student Scholarship blog posts showcase original scholarship written by Baylor students who conducted research using primary source materials in The Texas Collection. This post is the second of five in a series of blog posts written by graduate and PhD students from the Fall 2018 Foundations & History of Higher Education Leadership course.

by Rachel Jones, Rachel Ticknor, Rachel Henson, Jillian Haag, and Lela Lam

Following its merger with Waco University in 1886, Baylor University set forth a series of initiatives that were progressive in terms of extending college access to various student groups-specifically to women and transfer students. These initiatives included Baylor’s promotion of coeducation and the university’s establishment of formal articulation agreements with Texas high schools and other Baptist colleges. Because of these efforts, a Baylor education had become more accessible to a wider network of students. However, despite these progressive strides, some students (mainly female students) still faced inequality and a lack of access to certain resources/activities once they actually matriculated on campus.

With the establishment of the Baptist General Convention of Texas (BGCT)’s Education Commission in 1897, Baylor focused on leveraging the Commission’s existing partnerships in order to create formal articulation agreements with the other correlated Baptist colleges. Under these agreements, students that completed a standardized two-year curriculum and graduated from the affiliated colleges could transfer to Baylor, without an entrance examination, in order to complete their four-year degree. Baylor utilized a similar model in order to establish formal articulation agreements with a variety of high schools. These two initiatives collectively increased access for, and enrollment of, students who graduated from the affiliated high schools and colleges.

Despite their successes, it is possible that some of Baylor’s most groundbreaking initiatives were inherently exclusionary towards students who did not belong to/identify with the parameters that had been established (e.g. students who did not attend the affiliated high schools or colleges). Moreover, Baylor did not ensure that all students would receive equal levels of access to campus resources and programs once they actually enrolled at Baylor, which resulted in a sense of tension among the university community.

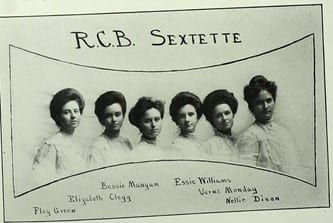

This tension is perhaps most evident in the experiences documented by Baylor’s female students and faculty members between 1900 and 1910. Although Baylor had taken a rather progressive stance on coeducation and allowed men and women to meet in the classroom and in the chapel together, women still faced unfair treatment in terms of housing policies and educational, financial, and extracurricular opportunities. Two examples of this treatment are evident when one takes a closer look at the student literary societies and faculty job opportunities.

As with most topics regarding student access during this time, the issue of women’s participation in literary societies was complex. There was collaboration and partnership between the male and female societies, but this did not always result in equality for their respective members. Though there were a number of benefits that came from women’s membership in literary societies, it is evident that when compared to their male counterparts, female students who chose to participate in such societies faced marginalization. This marginalization is especially evident when one considers the limited opportunity for scholarships.

In a similar vein, female faculty members at Baylor also experienced inequality. Although Baylor had taken a progressive stance on hiring more female faculty members, women comprised less than half of the faculty, were paid less than their male counterparts, and were generally considered lower-level “instructors” rather than full professors. In addition, Baylor rarely hired married female faculty members, notwithstanding that the majority of male faculty were married. All of these examples confirm that Baylor female faculty members faced inequality that was similar to what Baylor female students faced.

As progressive as Baylor was in 1900 to 1910, it was still a far cry from the experience that Baylor women have today. Finally, as Baylor continues to extend access to a variety of students, the university should build intentional partnerships whilst remaining mindful of any possibilities of exclusion.

Research Ready: January 2019

Each month, we post an update to notify our readers about the latest archival collections to be processed and some highlights of our print material acquisitions. These resources are primed for research and are just a sampling of the many resources to be found at The Texas Collection!Continue Reading

Research Ready: October 2018

Each month, we post an update to notify our readers about the latest archival collections to be processed and some highlights of our print material acquisitions. These resources are primed for research and are just a sampling of the many resources to be found at The Texas Collection!Continue Reading

Research Ready: September 2018

Each month, we post an update to notify our readers about the latest archival collections to be processed and some highlights of our print material acquisitions. These resources are primed for research and are just a sampling of the many resources to be found at The Texas Collection!Continue Reading

Lives in the Archives: The A. Reilly and Eunice B. Tooley Copeland Papers

by Jackson Hager, Graduate Assistant

One of the great joys of being able to work in an archive like The Texas Collection is how often one, amid the stacks and piles of collections, encounters remarkably human stories. Even when the collection is just a few folders, an archivist can sometimes feel like they have encountered a real person, with all the flaws and perfections that come with being a human. That was my experience as I was processing the A. Reilly and Eunice B. Tooley Copeland papers, where I came to catch a glimpse of the Waco’s past through the eyes of a passionate Baptist preacher and his wife.

Antonio Reilly Copeland was born on January 7, 1889, in Marquez, Texas. His future wife, Eunice Bessie Tooley, was born in Buffalo Springs, Texas, on November 30, 1891. The couple first met in 1903 and married in the summer in 1916. While Eunice studied music in Houston, Reilly attended college first in Commerce, then Tehuacana, Rome, and finally the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. After the couple had had several children, the family made their entrance into Waco history when they moved there in 1923, as Reilly had been offered the pulpit at the Tabernacle Baptist Church, located at 1500 15th and Clay Street.

During his four decades of leading the Tabernacle community, Reilly was a prolific speaker and writer. His writings reveal a strong sense of right and wrong, and a zeal for adhering to what he saw as biblical truth. His confrontational style of writing, however, brought conflict. The most famous example of this is when Reilly was charged with criminal libel in 1925, after writing several letters detailing the moral failings of local Waco politicians. The charges were dropped in 1928, however, and Reilly continued to preach and write. He spent the latter half of his career delving deep into biblical study and debate. As evidenced by his letters, Reilly participated often in the debates surrounding Fundamentalism and Neo-Orthodoxy, and his journals show a deep interest in biblical prophecy and how it related to world at large. Reilly’s preaching was not just reserved for the pulpit, as he hosted a radio program for station WACO from 1941 to 1954. By the time of his resignation in the early 1960’s, Reilly had been a public voice for Baptists within the Waco community for almost forty years.

While Reilly’s writings may provide one picture of who he was, Eunice’s own memoirs help fashion a fuller image. Eunice dedicated more than half of her book to her time with Reilly and the family they made together, and we find that Reilly was a kind and loving husband and father. Eunice’s writings help shine a light on what it was like to be a preacher’s wife in the early 20th century, and how they dealt with the many changes that occurred during those turbulent years.

The lives of A. Reilly and Eunice Copeland may appear, in the grand scheme of things, of little impact. But it is through the small, personal stories of regular people that we obtain a deeper human connection to our past.

If you are interested in learning more about A. Reilly and Eunice Copeland, feel free to contact us at The Texas Collection and view the collection’s finding aid here!

We Want That Picture! Fred Gildersleeve’s Record Breaking Texas Cotton Palace Print

By Geoff Hunt, Audio and Visual Curator

In 1905 or 1906, Fred Gildersleeve came from Texarkana, Arkansas to Waco to work in the photography business. He later became a pioneer in the field of industrial photography in the state. One of his more famous pieces of work was his enlargement of the Texas Cotton Palace Main Building in Waco, Texas. Shown is a picture of the enlargement being processed. At the time, this photograph set a world record among photo prints at 120 inches wide. A representative from Eastman Kodak personally delivered the large roll of photo paper it required and supervised the enlargement process. The photo was exhibited for some time until it was sold for $50.00 to the building’s architect, Roy Ellsworth Lane. Gildersleeve later recalled that was “a good price in those days…as you remember, at that time 1913 the largest enlargement ever made. Eastman Kodak sent George McKay to supervise this. It was written up in Studio Light Magazine and also used this photo.”Continue Reading

Research Ready: July 2018

Each month, we post an update to notify our readers about the latest archival collections to be processed and some highlights of our print material acquisitions. These resources are primed for research and are just a sampling of the many resources to be found at The Texas Collection!Continue Reading

Part II: A History of the Baptist Joint Committee and the Protection of Religious Liberty

Baptist Joint Committee records, Accession #3193, Box #652, Folder #23, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

by Thomas DeShong, Project Archivist

This blog is the first of two that highlights a recently processed collection, the Baptist Joint Committee records, and its place in history.

The 1930s were a desperate time in the history of the United States. The nation had been plunged into the Great Depression following the crash of the stock markets. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his brain trust crafted the New Deal in an effort to combat unemployment and economic depression. In order to enact Roosevelt’s proposals, however, the powers of the federal government began to increase dramatically. Concerned about potential infringements on individual freedom, particularly religious liberty, Baptists across the country began to organize.

In 1936, the Southern Baptist Convention created a Committee on Public Relations to monitor the government’s activities. Rufus W. Weaver, a prominent Baptist educator and writer, served as its first Chairman. Under his leadership, the committee tackled various church-state issues including American attempts at diplomacy with the Vatican, the mistreatment of missionaries in Romania, and the formation of the United Nations. Weaver also facilitated cooperative efforts among the Southern Baptist Convention, the Northern Baptist Convention, and the predominantly African American National Baptist Convention U.S.A., Inc. to maximize their ability to enact change.Continue Reading

Research Ready: June 2018

Each month, we post an update to notify our readers about the latest archival collections to be processed and some highlights of our print material acquisitions. These resources are primed for research and are just a sampling of the many resources to be found at The Texas Collection!Continue Reading