They [people who do not like poetry] are totally ignorant that Poetry is identified and incorporated in the primitive elements of all that makes God visible, and man glorious…. These people have no ear for music in a “babbling brook,” without the said brook turns a very profitable mill. They find no “sermons in stone,” beyond those preached by the walls of a Royal Exchange. They see nothing in a mob of ragged urchins loitering about the streets in a spring twilight, busy over a handful of buttercups and daisies, lugged with anxious care from Putney or Clapham—they see nothing but a tribe of tiresome children who deserve, and sometimes get, a box on the the ears for “being in the way.” They see nothing in the attachment between a poor man and his cur dog, but a crime worthy the imprisonment of one, and the hanging of the other.

Eliza Cook

“People Who Do Not Like Poetry”

in Eliza Cook’s Journal (1849)

In “People Who Do Not Like Poetry,” Eliza Cook not only deprecates those who do not appreciate poetry written on pages or lived out in the world around them, but she also admires the poor who, lacking a knowledge of the technical details of poetic verses, nevertheless, find the spirit of poetry all around them.

She was the youngest of eleven children. Although primarily self-educated, Eliza was heavily encouraged by her mother to pursue her gifts and began to compose poetry as a young child, publishing her first volume, Lays of a Wild Harp, when she was only seventeen. The volume was well-received, and she began submitting poetry to magazines. For almost a decade she published Eliza Cook’s Journal, a weekly periodical.

Despite Cook’s popular appeal, her poetry was not admired by some of her literary contemporaries. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, in a letter to Mary Russell Mitford in 1845, stated that “Her [Cook’s] poetry, so called, I cannot admire—though, of course, she has a talent of putting verse together, of a respectable kind.” Likewise, Christina Rossetti told her brother he could call her “Eliza Cook” if he thought her verses mediocre.

Although her verses were not admired by either Elizabeth Barrett Browning or Christina Rossetti, at that time Cook was the most influential and widely read working-class author, editor, and essayist, according to Florence Boos in Working-Class Women Poets in Victorian Britain: An Anthology. Most popular among the working-class for her sentimental poetry, she ultimately used her strong voice to champion the causes of the underprivileged and to advocate political freedom for women. Boos notes that she wrote poetry about “factory conditions, concepts of ‘property,’ worker’s education, the dignity of manual labor, enclosure, church disestablishment, class distinctions, the wanton destruction of war, the griefs of emigration, … and the humane treatment of animals.”

The ABL owns five volumes of Eliza Cook’s poetry, several of which can be viewed at the Armstrong Browning Library – 19th Century Women Poets Collection page of the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections site. In addition, the ABL owns a letter from Eliza Cook to William Johnson Fox, which discusses her successful effort to raise money to furnish the grave of Thomas Hood, a popular Brisitsh humorist and poet, with a marker.

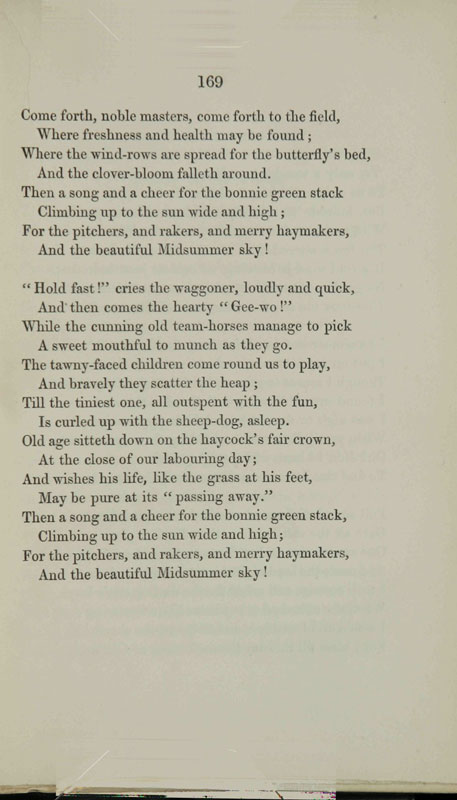

The poem below, “Song of the Haymakers,” is described in “Of ‘Haymakers’ and ‘City Artisans’: The Chartist Poetics of Eliza Cook’s Songs of Labor” by Solveig C. Robinson as “the most striking of Cook’s songs of rural England and agricultural labor.”

Eliza Cook

“The Song of the Haymakers”

Poems: Second Series (1864)