By Allison Scheidegger, PhD Student, Department of English, Baylor University

This spring, the Armstrong Browning Library is hosting “Puppy Love: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships,” an exhibition on dog ownership and depictions of dogs in the Victorian period, with a focus on Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, Flush. January 15, 2022 – August 15, 2022.

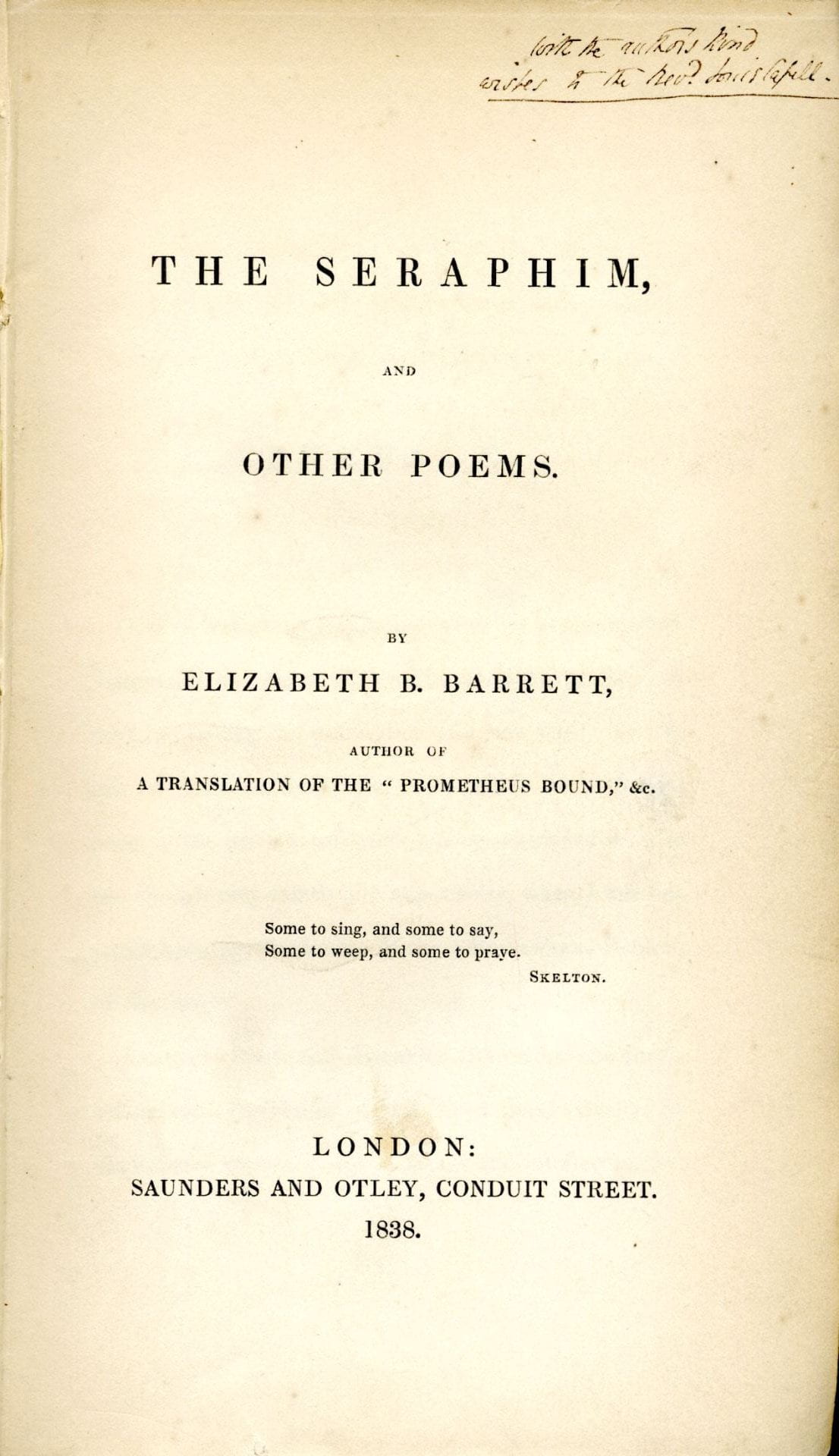

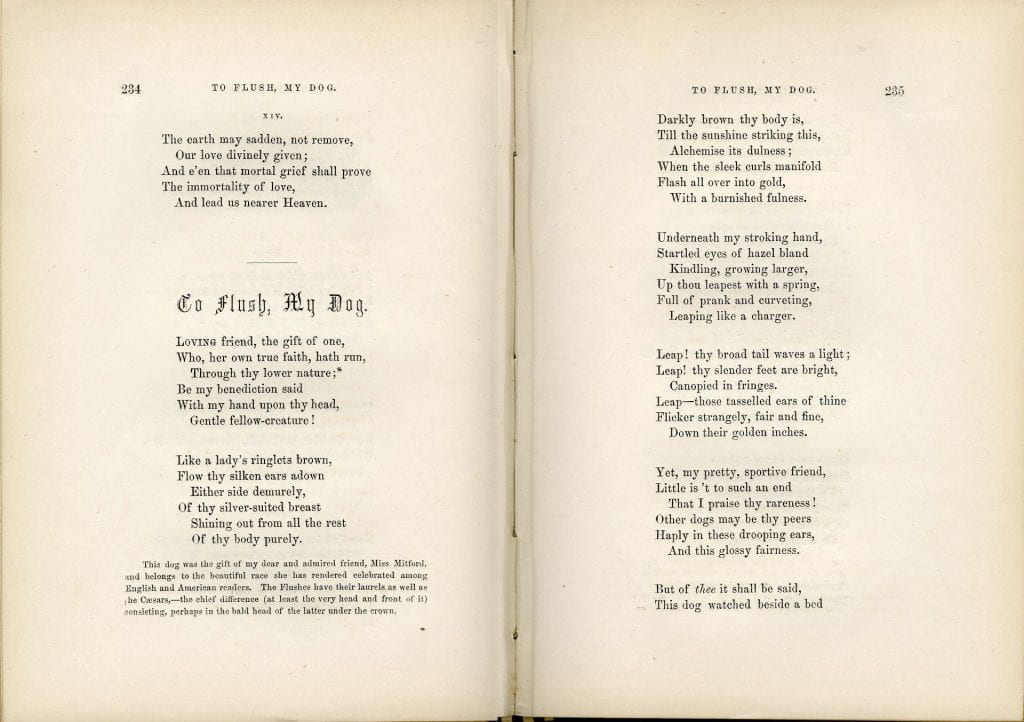

Although “Puppy Love” considers Victorian dog ownership and depictions of dogs more broadly, the exhibit concept began with Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel, Flush, and the literature he inspired. Elizabeth Barrett Browning to wrote two poems and multiple letters describing Flush’s appearance and antics. Nearly a century later, the modernist author Virginia Woolf revisited this celebrity dog in the novel Flush: A Biography, which retells Flush’s story through his own perspective. This blog post explores how Browning and Woolf viewed their own dog writings, how their popular and critical audiences received them, and how these perspectives illuminate cultural attitudes about female authors and animal writing.

In the nineteenth century, prejudice lingered regarding female authors’ ability to produce great literary works. In 1850, a writer for The English Review lamented,

Female Poetry! this scarcely seems to us, ungallant as we are, a delightful theme, or a glorious memory; for is it not, generally speaking, mawkish, lackadaisical, and tedious? To us, at least, it is. Look at the “Literary Souvenir,” or “Book of Beauty,” if you want to see the kind of thing we mean: what people denominate poetry of the affections. (Gurney)

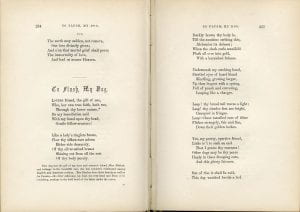

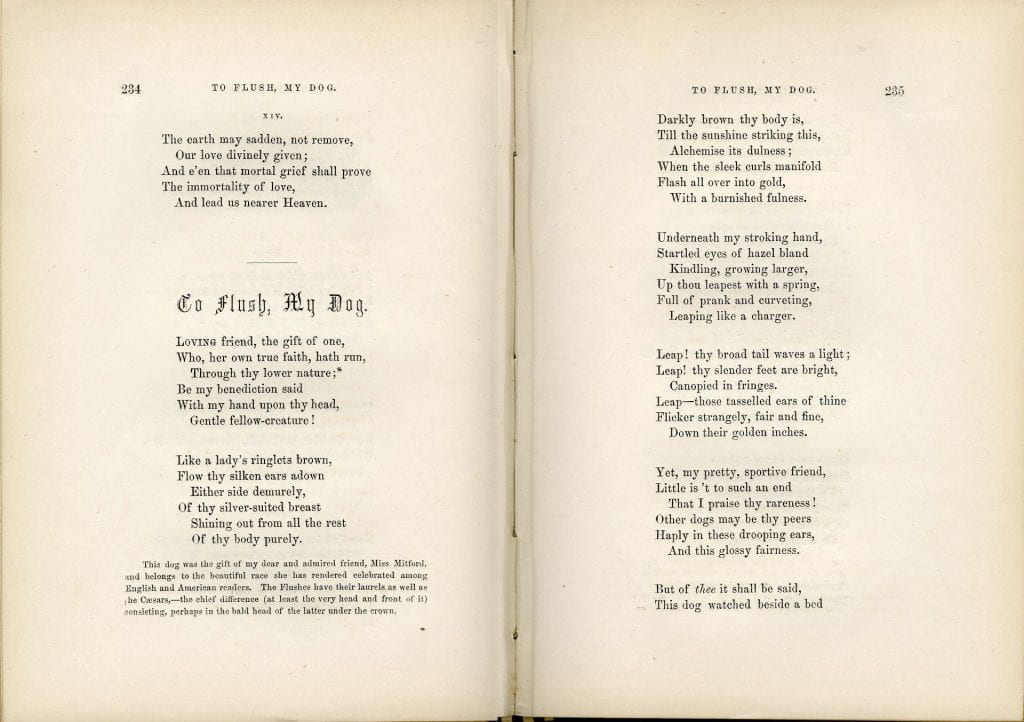

In this reviewer’s mind, female poetry is associated with mediocrity, dullness, and sentimentality: it is not true poetry. The reviewer explicitly exempts Browning from this critique and even counts the poem “To Flush, My Dog” among his favorites in the recent edition of Browning’s Poems. But despite this ultimately positive verdict, the threat of being dismissed as a “poet of the affections” would have been a real concern to Browning as she considered how the inclusion of such a “light” poem might affect her literary reputation.

Browning’s “To Flush” in The Poetic Album. 1854.

“To Flush” is certainly a poem of affection and sentiment, as Browning recognized. But Browning was determined to keep “To Flush” in Poems, despite the cautions of a few of her friends, because Flush was important to her.

Writing about animals as a female author was doubly dangerous. As still holds true today, animal stories were frequently written for the purpose of entertaining and educating children. By comparing and contrasting themselves with misbehaving pets or loyal and brave pets, children could learn a moral lesson. One of the most popular examples of this sort of book is Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s Lessons for Children, which E. B. Browning grew up reading.

-

-

Barbauld’s Lessons for Children. 1830.

-

-

Barbauld’s Lessons for Children. 1830.

-

-

Barbauld’s Lessons for Children. 1830.

Animal writing after Barbauld tended to target children, a trend of which the “Puppy Love” exhibition displays several examples. Because of this intended audience and the desire to teach moral lessons, animal writing was often highly sentimental and moralizing—harsh critics might lump animal writing with female poetry as “mawkish, lackadaisical, and tedious.” Despite this risk, and despite their budding reputations as serious female authors, both Browning and Woolf experimented with animal writing for the sake of Flush.

Authors’ Self-Perceptions and Critical Reception

Perhaps because of the common perception that animal writing was didactic, sentimental literature for children, both Browning and Woolf seemed to assume that their writings about Flush could not be serious literature. Browning dismissed “To Flush, My Dog” as light poetry and Woolf found Flush an embarrassment. When Browning shared “To Flush, My Dog” with friends before publishing it, she often described the poem critically. When Browning’s friend and mentor Hugh Stuart Boyd critiqued “To Flush,” she wrote in reply that she was “humbled” by his “hard criticism of [her] soft rhymes about Flush.” She admitted, “As for Flush’s verses, they are what I call cobweb verses, thin and light enough” and their significance is not “worth a defence” (Letter to Hugh Stuart Boyd). But Browning’s belittling of her work may be a kind of self-protection, a way to show that she is aware that animal poems are not serious and also to suggest that she is capable of greater things. Browning seems to want to set herself apart from the stereotypical female author who writes only such “cobweb verses.” Yet these supposedly “soft” verses grapple with interspecies relations, the death of a brother, and Browning’s mourning process.

The same is true of Flush: A Biography. Woolf was even more dismissive of her work: “I wanted to play a joke on Lytton – it was to parody him. But then it grew too long, and I dont think its [sic] up to much now” (23 February 1933, Virginia Woolf to Ottoline Morrell, Letters 5, 161–62). Lytton Strachey, the author of Eminent Victorians, wrote biographies in a detailed psychological style, commenting on Victorian culture through the study of individuals. Woolf thought it would be delightful to give as much (mock) serious attention to the life of an eminent Victorian dog. Woolf’s inspiration to write Flush came from reading the correspondence between Robert and Elizabeth Browning: “I was so tired after the Waves, that I lay in the garden and read the Browning love letters, and the figure of their dog made me laugh so I couldn’t resist making him a Life” (Woolf to Morrell 161). Following the Browning correspondence, Flush traces the story of the Brownings through their courtship, marriage, and escape from London to Italy, but with the difference that the events are filtered through the perspective of Flush. This perspective shift enables Woolf to engage in social and psychological exploration. The first meeting of Browning and Flush, for example, does not read like a lighthearted pet story for children.

-

-

Woolf’s Flush: A Biography. 1933.

-

-

Woolf’s Flush: A Biography. 1933.

Although Woolf says that Flush is a “joke,” the mock biography deals with serious issues such as animal psychology, eugenics, and fascism. Woolf’s self-evaluation of Flush and her judgment that it is “not up to much now” seem to overlook its significance.

Ultimately, such postures as Woolf’s and Browning’s are responses to a shared sense that they have jeopardized their literary reputations by dabbling in animal writing as female authors. Woolf worried that the publication of Flush would ruin her reputation as a serious author. She counseled herself in her diary to remember that she produced quality writing and that Flush was a rare aberration:

Flush will be out on Thursday & I shall be very much depressed, I think, by the kind of praise. They’ll say its “charming” delicate, ladylike. And it will be popular. . . . And I shall very much dislike the popular success of Flush. No, I must say to myself, this is a mere wisp, a rill of water; & so create, hardly [?] fiercely, as I feel now more able to do than ever before. (Diary 4, 181)

“Charming” was, at least in Woolf’s mind, the most offensive praise for a female author to receive. Both Browning and Woolf did in fact receive this critical verdict on their Flush pieces. An American reviewer, for example, characterized “To Flush” as “a charming little copy of verses to the Poet’s Dog” (Mathews). In general, critics judged Browning’s “To Flush” more favorably than Woolf’s Flush, perhaps due to the passing of a century and shifting expectations for female authors. Browning’s cousin John Kenyon reported that “To Flush” was one of John Forster’s favorites from Browning’s recently released Poems: “Dog Flush was a great favorite of his from the mixture—he says—of humor and tenderness” (Kenyon). Although some critics bewailed sentimental “Female Poetry,” writers of “charming” poetry in the mid-nineteenth century were not quite so despised in the mid-nineteenth century as they were in the mid-twentieth.

Popular Reception and Economic Considerations

Although Browning and Woolf (and some of their critics) disparaged the Flush writings, their readers felt differently. Both “To Flush, My Dog” and Flush: A Biography enjoyed significant popular success. “To Flush, My Dog” first appeared in the Athenaeum, then was included in Browning’s Poems (which was appeared in multiple editions), in addition to being frequently selected for inclusion in poetry collections like The Poetic Album above. Woolf’s Flush-focused novel earned still more significant popular (and therefore financial) success. According to Anna Snaith, Flush sold almost 19,000 copies within six months, thus becoming Woolf’s “best-selling novel in Britain” (618).

Given Woolf’s intense dread of Flush being popular, it is ironic that she needed Flush to be popular. After the failure of her previous work, The Waves, Woolf hoped that her “little escapade” of writing Flush could provide some financial support (16 September 1931, Virginia Woolf to Vita Sackville-West, Letters 4, 380). While Browning, who relied on her father’s comfortable means, did not have to support herself by writing popular poems, other female authors were not so fortunate. In this awareness of the financial pressures of authorship, Woolf resembles E. B. Browning’s friend Mary Russell Mitford, who served as editor of and contributor to Findens’ Tableaux in order to support herself and her father. These may not have been the prestigious works she wished to write, but they sold well.

However, commercial success was a third strike against animal writing by female authors. As Woolf recognized, a work’s popularity and feminine “charm” nearly guaranteed an icy critical reception. A look back at the past century reveals why Woolf made this assumption. The Victorian and Edwardian era was marked by the proliferation of ornate collector’s albums of sentimental poems and stories, often written by and for women. Mary Russell Mitford’s Findens’ Tableaux is an example of such an album. The critic from The English Review who condemned “Female Poetry” also specifically castigates poets who contribute to sentimental collections. About the poet L.E.L, he rants,

This woman undertook for years to fill a large annual with nothing but her poetry, in illustration of certain prints to be furnished her, whatever they might be! Now this fact alone expresses far more than any condemnation of ours could do. What a vista of dreary, morbid, boundless common-place does this disclose to us! And contemporary criticism could applaud, could think this annual undertaking perfectly natural, and rather sublime.

Although the reviewer heaps shame on L.E.L. while excusing E. B. Browning, Browning’s poems would also appear in such contexts. “To Flush, My Dog” and “Flush or Faunus” both appear in The Poetic Album (1854), a collection which places decorative engravings of ladies’ heads alongside poetry, with little regard for relevancy. The social and economic pressures on female authors, particularly when compounded with the lowly status of animal writing, often placed them in the difficult position of risking their literary reputation because of financial need or (in the case of Browning) because of their real affection for the subject of their work. Perhaps saddest of all, existing stereotypes made female authors reticent to consider their animal writing worthwhile.

Works Cited

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett. Letter to Hugh Stuart Boyd. 6 [or 8] September 1843.

—. “To Flush, My Dog.” In The Poetic Album: Containing the Poems of Alfred Tennyson, Mrs. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Alexander Smith. Willis P. Hazard, 1854.

Gurney, Archer Thompson. “Poetesses—Mrs. Browning and Miss Lowe.” The English Review, December 1850, pp. 320–332. As reprinted in The Brownings’ Correspondence, 16, 325–329.

Kenyon, John. Letter to Elizabeth Barrett Browning. 4 October 1844. Browning Correspondence.

Mathews, Cornelius. “A Drama of Exile.” The United States Magazine, and Democratic Review, October 1844, pp. 370–377. Reprinted in The Brownings’ Correspondence, vol. 9, pp. 340–345.

Snaith, Anna. “Of Fanciers, Footnotes, and Fascism: Virginia Woolf’s Flush.” Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 48 no. 3, 2002, p. 614-636.

Woolf, Virginia. The Letters of Virginia Woolf. Edited by Nigel Nicholson and Joanne Trautmann, vol. 4: 1929-1931, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

—. The Letters of Virginia Woolf. Edited by Nigel Nicholson and Joanne Trautmann, vol. 5: 1932-1935, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

—. The Diary of Virginia Woolf. Edited by Anne Olivier Bell, assisted by Andrew McNeillie, vol. 4: 1931-1935, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977.

—. Flush: A Biography. Hogarth Press, 1933.

Read more in this series of blog posts about the exhibit “‘Puppy Love’: An Exploration of Victorian Pet-Owner Relationships”: