By Melinda Creech

Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

Joseph Milsand (1817-1886) was a French critic, philosopher, theologian, and close friend of Robert Browning. The Joseph Milsand Archive, now owned by the Armstrong Browning Library, contains over 4,000 autograph letters as well as numerous rare books, pamphlets, journals, photographs, drawings, newspapers, and albums. It includes original manuscripts of nearly all of Milsand’s known writings, together with a large number of annotated proofs and most of his printed works, documenting his career from the age of twenty until his death. Over 62,000 manuscript pages of Milsand’s articles, essays, study notes, and personal journals (mostly handwritten in French) record his thoughts and observations relating to the Brownings, the Milsand family, and the Anglo-French literary scene from the 1860s to 80s.

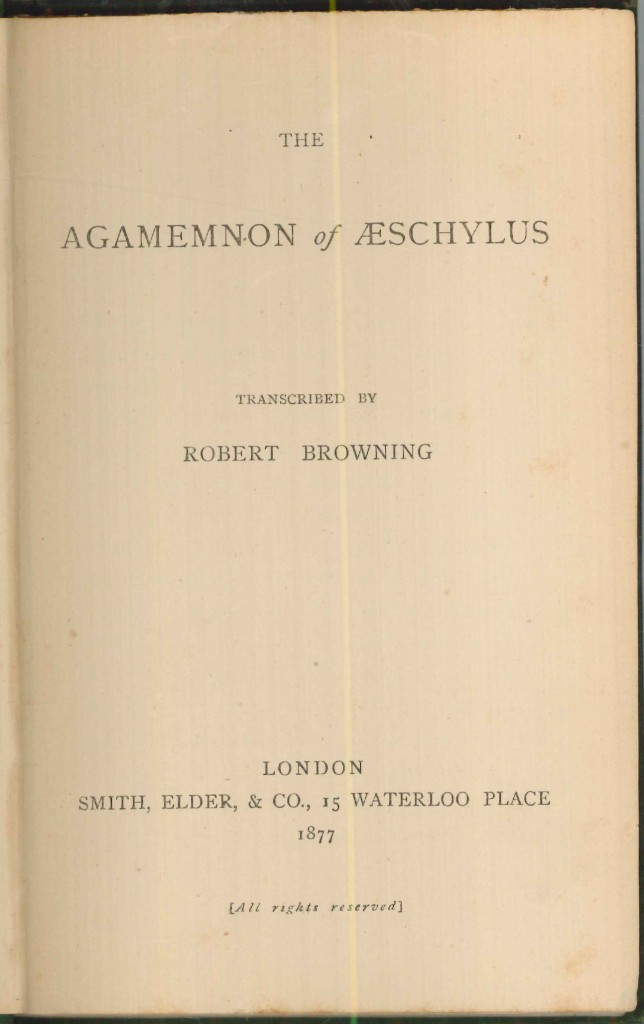

Milsand, who often wrote for the French journal, Revue des Deux Mondes, published two articles about Ruskin in that periodical, “Nouvelle theories de l’art, en Angleterre” 1 July 1860, and “De l’influence de la littérature,” 15 August 1861. The two articles, along with a preface, were published as a book, L’Esthétique anglaise, étude sur John Ruskin, in June 1864.

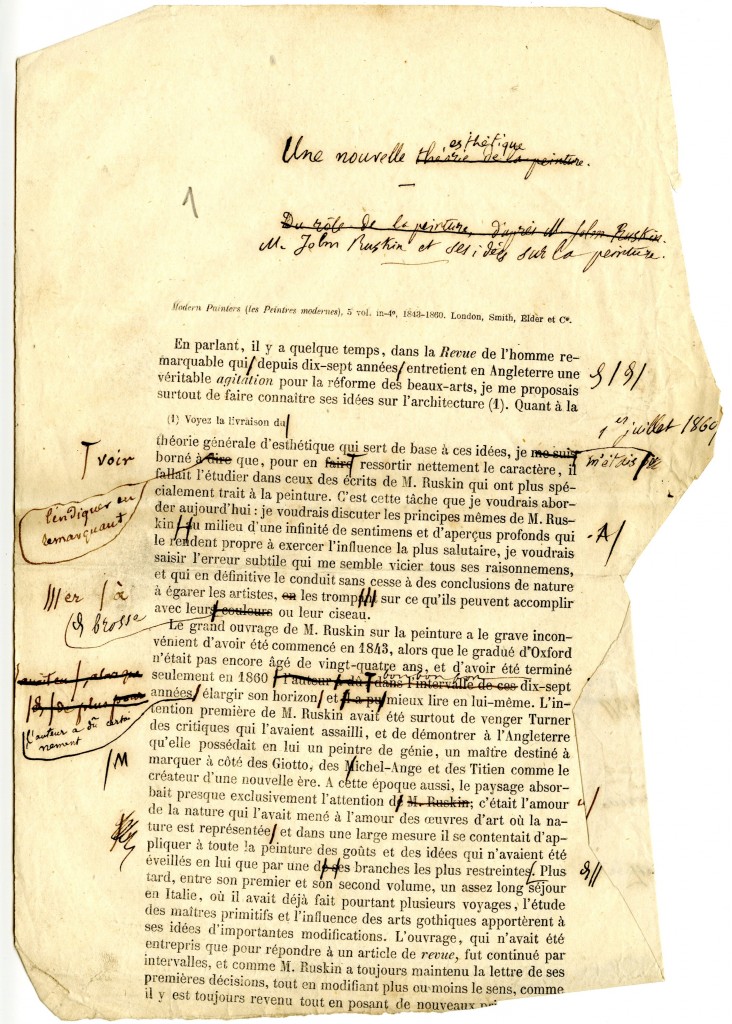

Shown below is Milsand’s copy of his first publication on John Ruskin, “Nouvelle theories de l’art en Angleterre.”

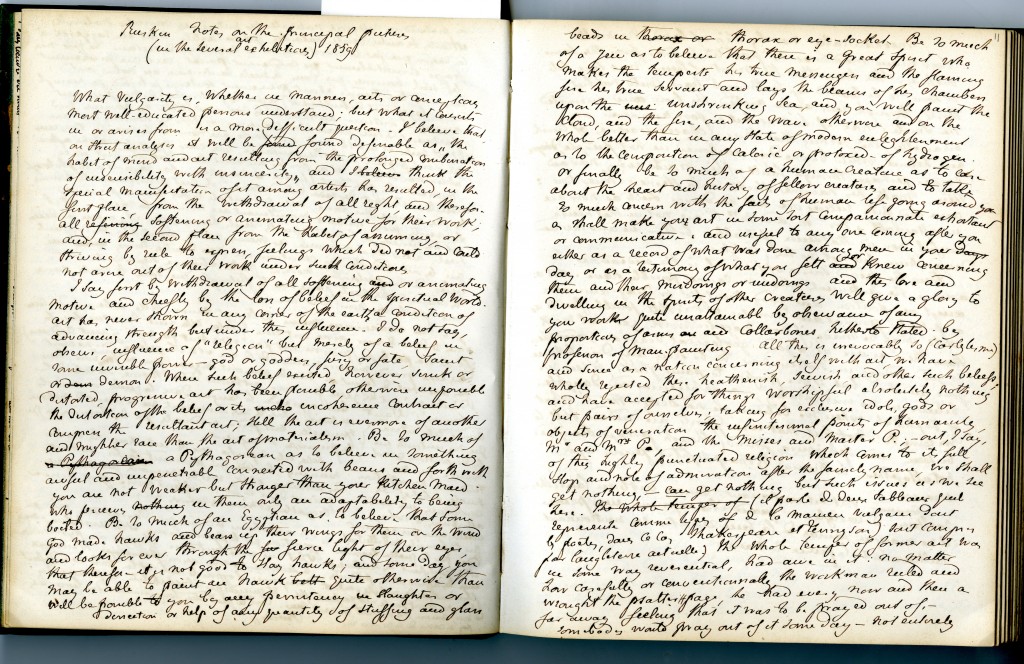

Several pages of Milsand’s notes on John Ruskin can be found in this journal kept from 1850-65.

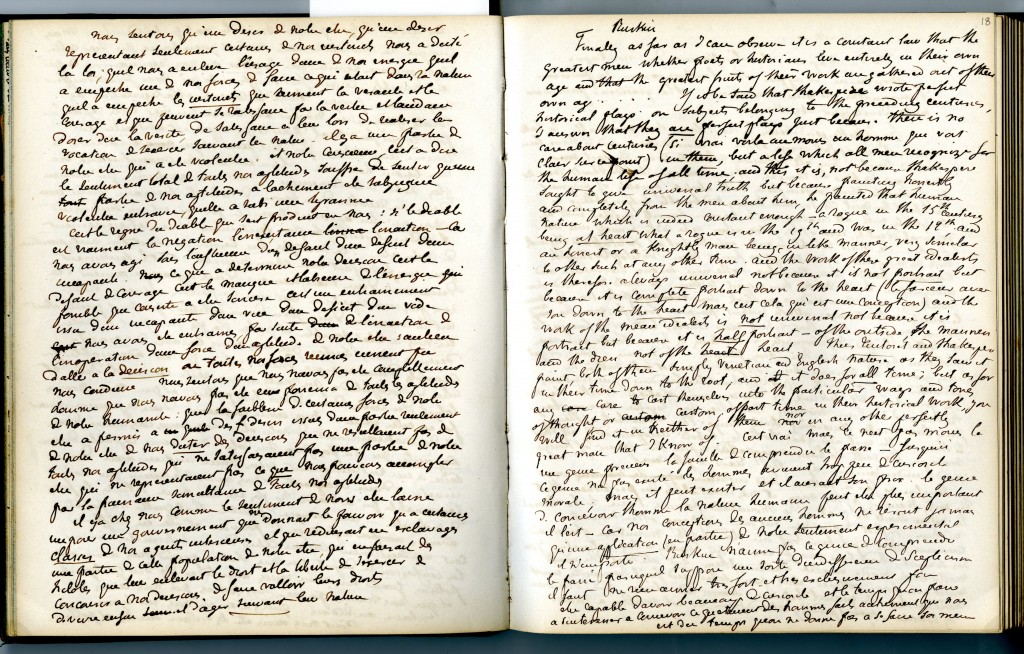

The Armstrong Browning Library also owns twenty-four pages of heavily revised galley proofs of the article, “Nouvelles theories de l’art en Angleterre,” which was published in Revue des Deux Mondes, 1 July 1860.

The Armstrong Browning Library also owns twenty-four pages of heavily revised galley proofs of the article, “Nouvelles theories de l’art en Angleterre,” which was published in Revue des Deux Mondes, 1 July 1860.

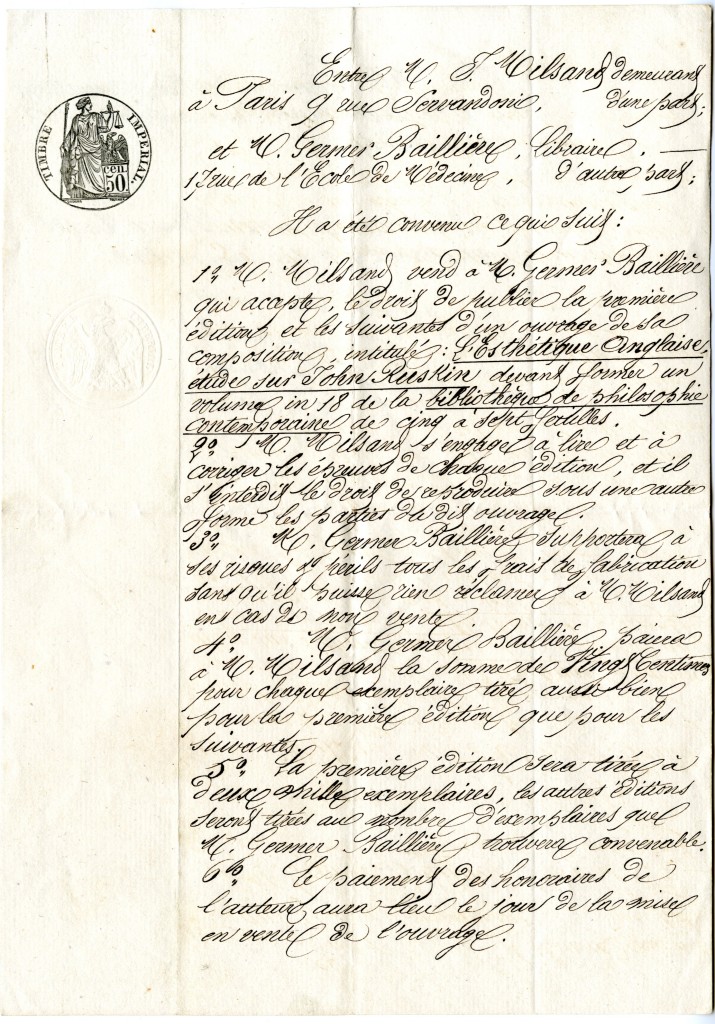

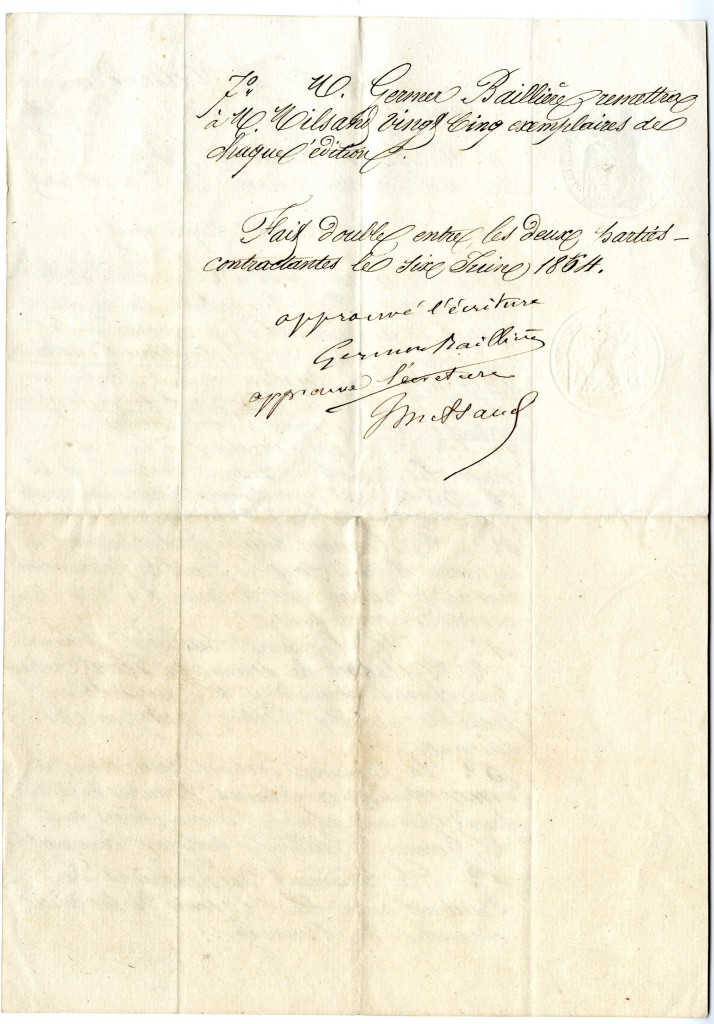

Milsand collected this article about Ruskin, “Nouvelles theories de l’art en Angleterre,” and another article also published in Revue des Deux Mondes, 15 August 1861, “De l’influence de la littérature,” written the next year, and added a preface to complete a book on John Ruskin, L’Esthétique anglaise, étude sur John Ruskin (1864). The following is a contract Milsand signed with Germer Baillière for the publication of L’Esthétique anglaise, étude sur John Ruskin (1864), dated 6 June 1864.

Milsand collected this article about Ruskin, “Nouvelles theories de l’art en Angleterre,” and another article also published in Revue des Deux Mondes, 15 August 1861, “De l’influence de la littérature,” written the next year, and added a preface to complete a book on John Ruskin, L’Esthétique anglaise, étude sur John Ruskin (1864). The following is a contract Milsand signed with Germer Baillière for the publication of L’Esthétique anglaise, étude sur John Ruskin (1864), dated 6 June 1864.

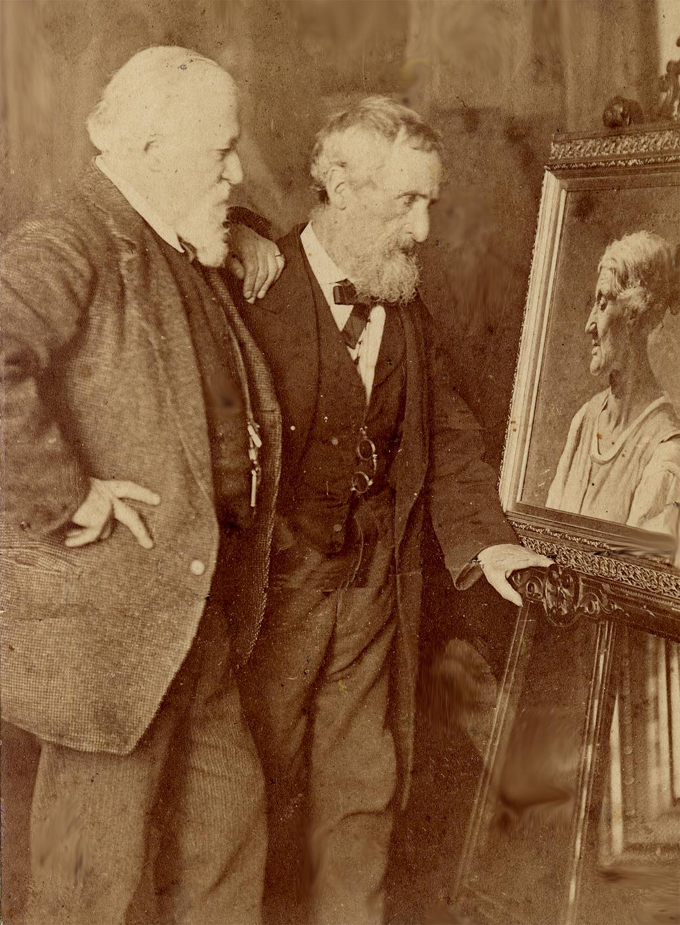

The Armstrong Browning Library also owns two letters written from John Ruskin to Joseph Milsand related to Milsand’s critique of Ruskin’s Modern Painters in his book, L’Esthétique anglaise, étude sur John Ruskin.

The Armstrong Browning Library also owns two letters written from John Ruskin to Joseph Milsand related to Milsand’s critique of Ruskin’s Modern Painters in his book, L’Esthétique anglaise, étude sur John Ruskin.

On 12 February 1865, John Ruskin wrote to Joseph Milsand, offering him thanks for the “deep and careful” praise given in Milsand’s review of Modern Painters. Ruskin tells Milsand that he accepts “his strictures as heartily and frankly as I do your praise,” affirming that “nothing has given me so much encouragement—or so much of the rare happiness which comes of a discovered sympathy, as your review of me.”

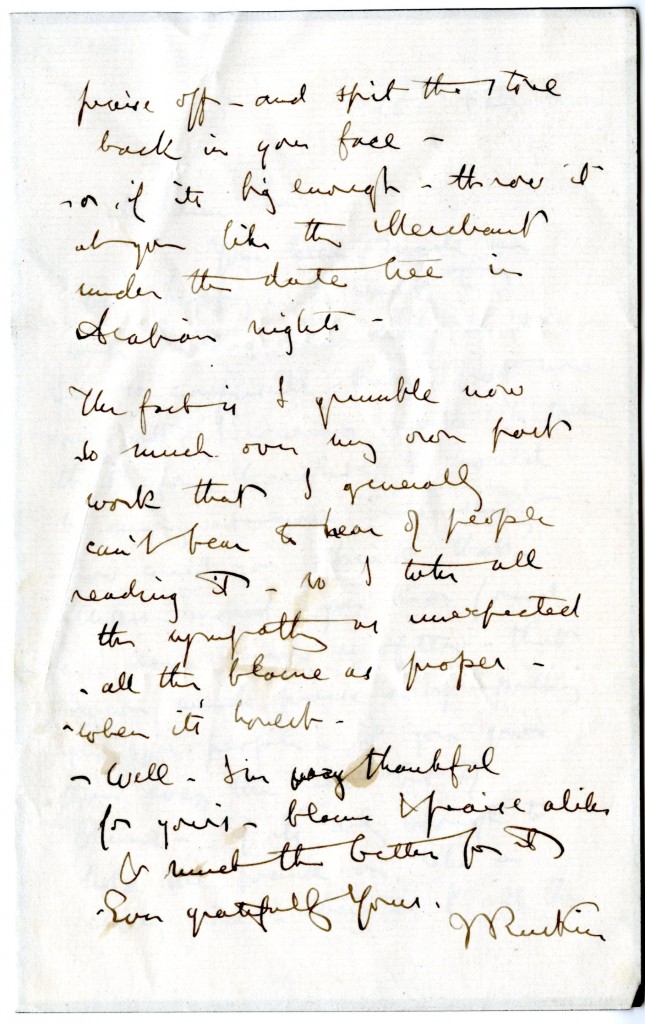

In the following letter, 28 February [1865], Ruskin thanks Milsand for his letter of response. He says that Browning had written to him saying that he thought Milsand would think Ruskin would have been angry about his criticism. However, Ruskin says this about praise and censure:

“…how could you think that? Unless indeed you have found as I have found so often that however much praise or sympathy you give people if you give them even the least bit of blame if it’s only enough to hold the praise on, like a cherry stone—they suck all the praise off—and spit the stone back in your face—or, if its big enough—throw it at you like the Merchant under the date tree in Arabian nights…. I’m very thankful for yours—blame & praise alike & much the better for it.”

![John Ruskin to Mrs. Johnson. [31 January 1865].](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/10/Ruskin-to-Johnson-1-16kewxa-641x1024.jpg)