By Denae Dyck, PhD Candidate, University of Victoria, Canada

For two weeks in March, I spent time as a visiting scholar at the Armstrong Browning Library (ABL). I am grateful to have had the opportunity to do research at a library with unique and extensive collections related to the texts, writers, and intellectual traditions that I am examining in my PhD studies at the University of Victoria, Canada. My dissertation looks at the uses of biblical wisdom literature by Victorian writers responding to the higher criticism, criticism that broke new ground by approaching the Bible primarily as a composite, historical, and literary document. This focus means that I am interested not only in the particular place of this wisdom literature within changing ideas about authority and revelation in nineteenth-century thought but also in the broader field of hermeneutics. Working with manuscripts and marginalia at the ABL has helped me to think about the task of interpretation from some new angles.

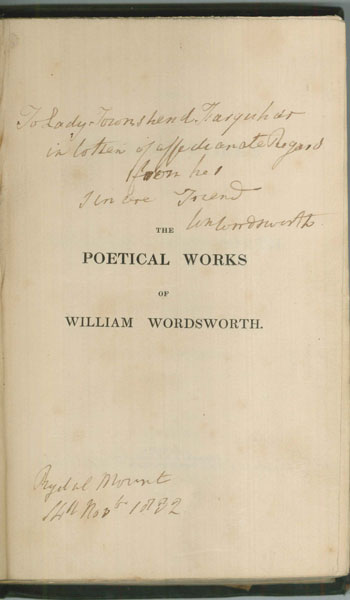

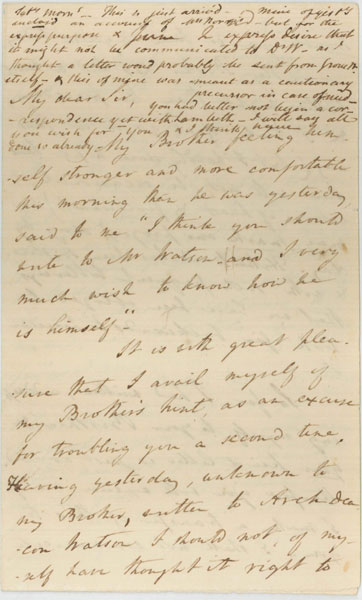

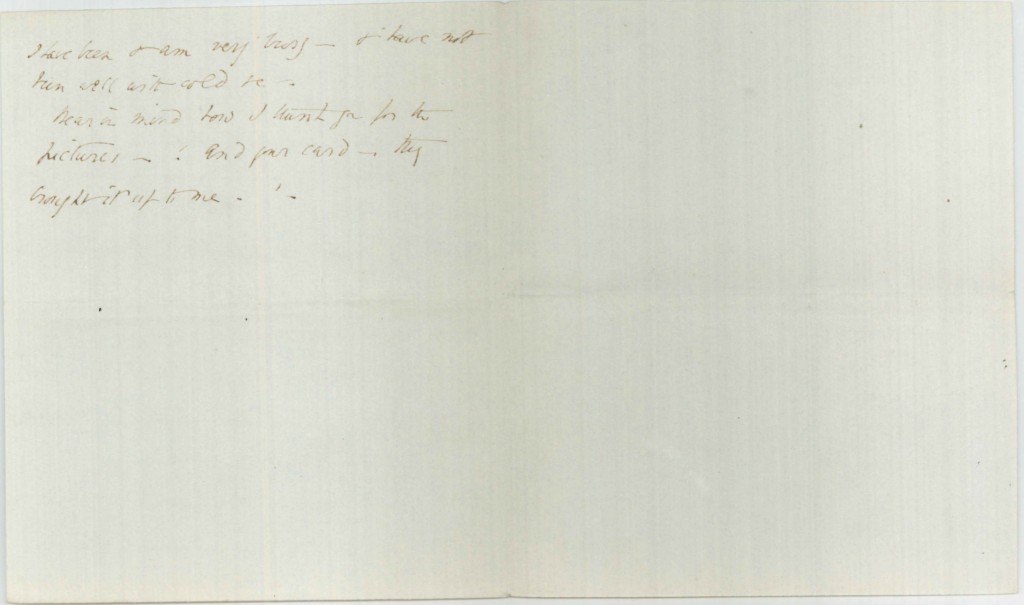

Among the many intriguing materials at the ABL, the autograph manuscript of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s (EBB’s) A Drama of Exile (her poetic engagement with the biblical narrative of humankind’s expulsion from Eden) held special interest for me because this poem is one of the primary texts that I am analyzing in my dissertation. Beginning where the third chapter of Genesis concludes—the fallout of the fall, if you will—EBB’s dramatic poem of 2272 lines takes up questions about the order of the cosmos and the meaning of suffering, the very questions raised by biblical wisdom literature, especially the book of Job. First published in 1844, A Drama of Exile incorporates elements of an earlier, unpublished piece entitled “Adam’s Farewell to Eden in His Age,” which is also held at the ABL and which has recently been published in the fifth volume of The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning (2010). Through studying the manuscript of A Drama of Exile at the ABL, I was able to further trace the development of EBB’s thought.

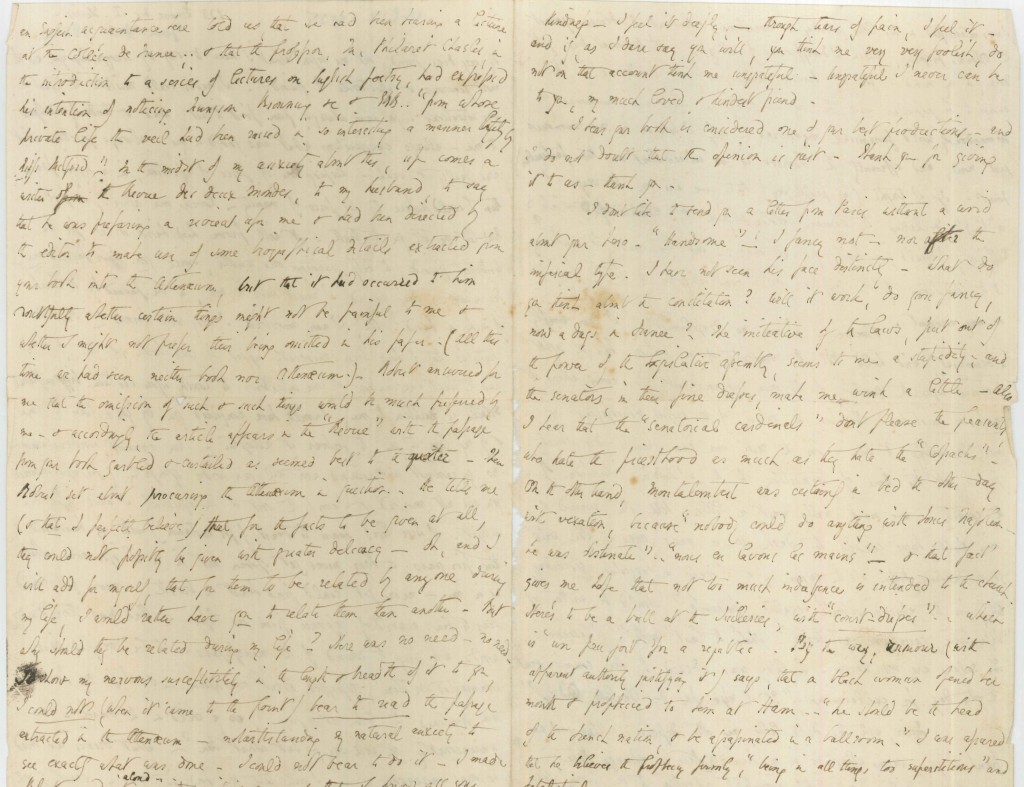

The experience of transcribing EBB’s small (and sometimes untidy) handwriting gave me the thrill of seeing familiar lines made strange: her manuscript differs from the published text in subtle yet interesting ways. As I found, seemingly small changes in word choice or sentence structure often reflect larger patterns and themes. For instance, whereas this manuscript compares the angelic songs heard by Adam and Eve in the wilderness to a “healing rain,” the published poem likens this music to a “watering dew,” a simile that brings Edenic imagery into the wilderness. Changes such as these intensify EBB’s overall emphasis on divine immanence within the mortal, material world. Although this manuscript does not include the entire poem, I was delighted to find that it contains two variants of EBB’s first scene with Adam and Eve. Comparing these versions against each other and against the published text of A Drama of Exile shows the non-linear elements of EBB’s writing process: even though one draft had more similarities to the final text than the other, the published poem includes distinctive elements from both fragments. One page from what I take to be the latter of these two versions offers an exciting glimpse into EBB’s thought. In the margins of a speech wherein Eve declares “since I was the first in the transgression, with my little foot / I will be the first to tread from this sword-glare / Into the outer darkness of the waste,” EBB has pencilled in an “x” and commented at the bottom of the page, “I do not like ‘little’ – it is almost coquettish—with my firm foot?” In the published version, the line reads “with a steady foot” (l. 547). This substitution reinforces EBB’s reinterpretation of Eve from the original sinner blamed in centuries of patriarchal exegesis to a figure of strength and insight.

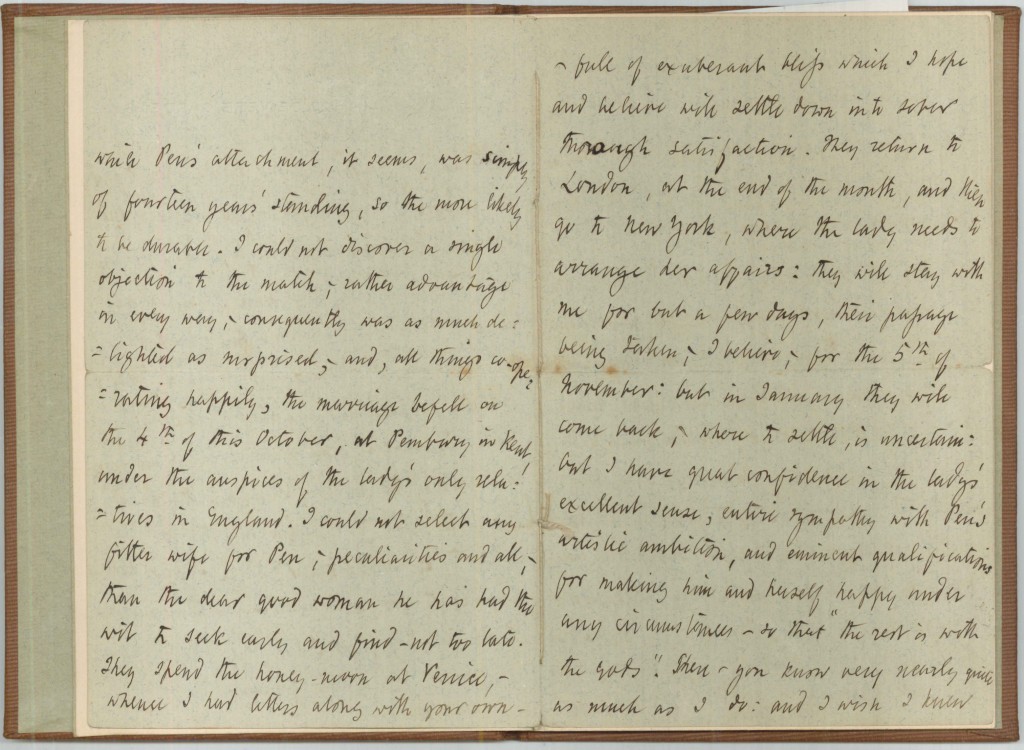

While this annotation shows the dialogue of the poet’s mind with itself, I was able to further explore the exchange of ideas that shaped A Drama of Exile through perusing unpublished letters to EBB from her cousin John Kenyon. Reading these letters allowed me to fill in some of the missing pieces from the multi-volume collection of The Brownings’ Correspondence, which contains EBB’s letters to Kenyon but not all of his to her. Kenyon played an interesting role in the poem’s formation: when EBB fell into despair and felt inclined to burn her manuscript, her cousin intervened by offering to give her his honest opinion, as EBB explains to her scholarly mentor H.S. Boyd in a letter that is included in The Brownings’ Correspondence (volume 8, pp. 267-68). The letters from Kenyon at the ABL, which date from sometime after this incident, provide both encouragement and critique. He tells EBB, “The more I read of your poem the more I admire & love it”; nevertheless, he also questions some of her archaic diction choices (“Why do you – who taught me to say – between – say betwixt?”) and makes suggestions involving characterization. These letters reinforce that the process of composition does not take place in a vacuum.

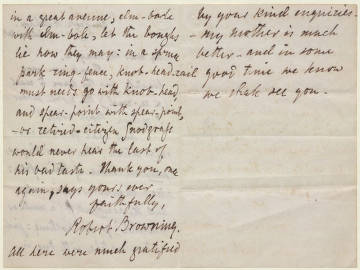

![Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Detail of Marginalia in Xenophon’s Memorabilia. Page 181. [ABLibrary Brownings’ Library XBL 888.3x55m]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-3-10qn32q-225x300.jpg)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Detail of Marginalia in Xenophon’s Memorabilia. Page 181. [ABLibrary Brownings’ Library XBL 888.3x55m]

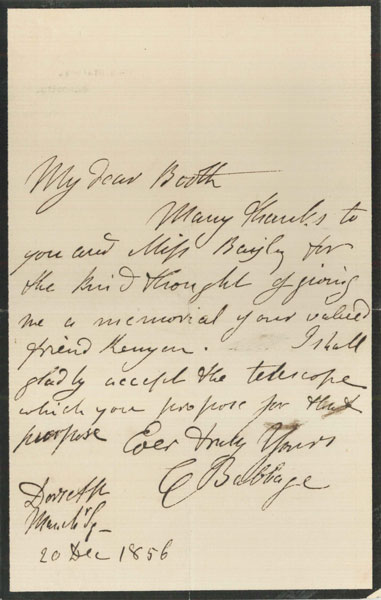

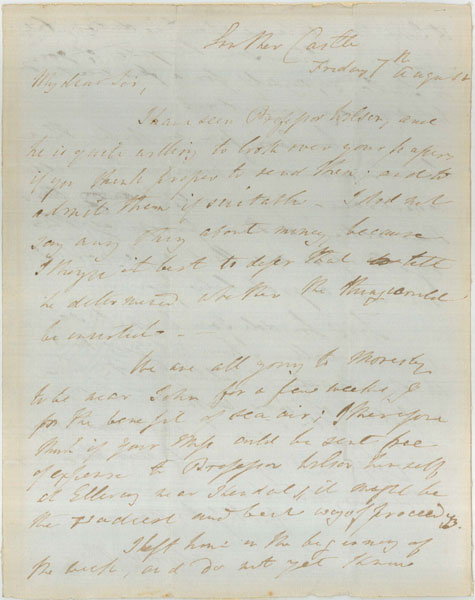

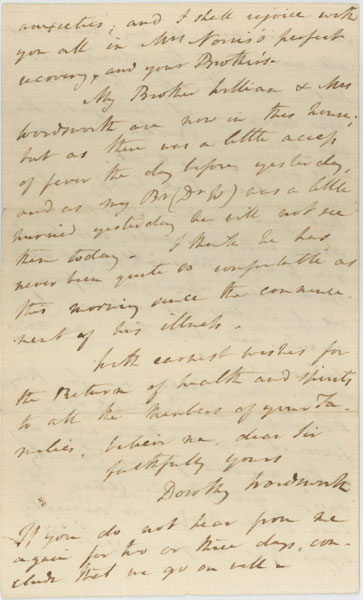

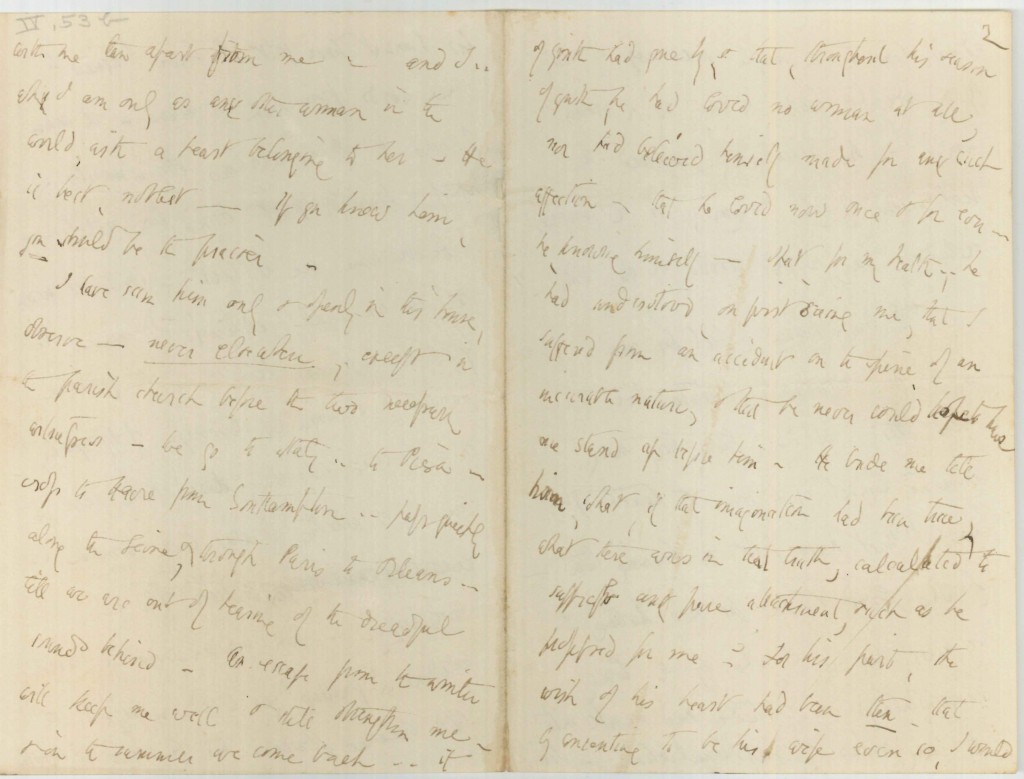

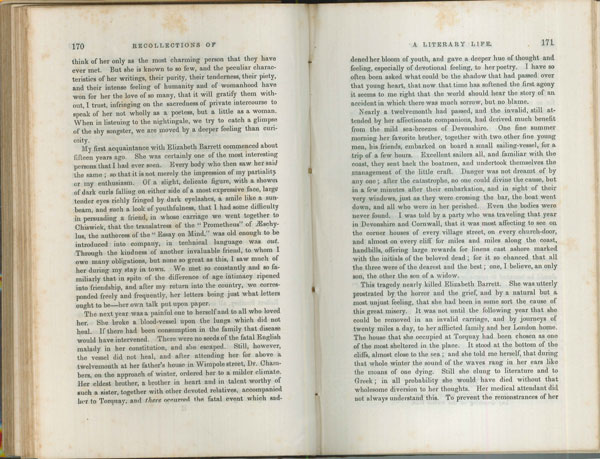

In addition to manuscripts and unpublished letters, the ABL has a large collection of books from the library of EBB and Robert Browning that show the breadth and depth of these two poets’ intellectual engagement—all the more so because many of these volumes contain marginal notes. For instance, EBB’s markup in her four-volume set of Henry Hallam’s Introduction to the Literature of Europe of the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Seventeenth Centuries (1837) critiques Hallam’s arguments on subjects ranging from the Protestant Reformation to John Donne’s poetry. Such marginal commentary underscores the fact that creative writing is often a form of rewriting—A Drama of Exile, for instance, responds not only to biblical texts but also to John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), along with other literary precedents. Given my interests in hermeneutics and wisdom literature, I was curious about the Brownings’ volumes of Socratic dialogues and their notations therein. As I discovered, these notes highlight points of intersection between classical and biblical traditions. In her copy of Xenophon’s Memorabilia, EBB likens Socrates’ words about the duties of a general to the pastoral advice given in 1 Timothy chapter 3. The holdings from the Brownings’ library also include their copy of Introduction to the Dialogues of Plato (1836) by Friedrich Schleiermacher, the theologian whose work brought together religious and secular hermeneutics. The pencil markings in this book call attention to Schleiermacher’s view of dialogue not merely as a rhetorical trick but, more importantly, as a method for catalyzing the search for knowledge.

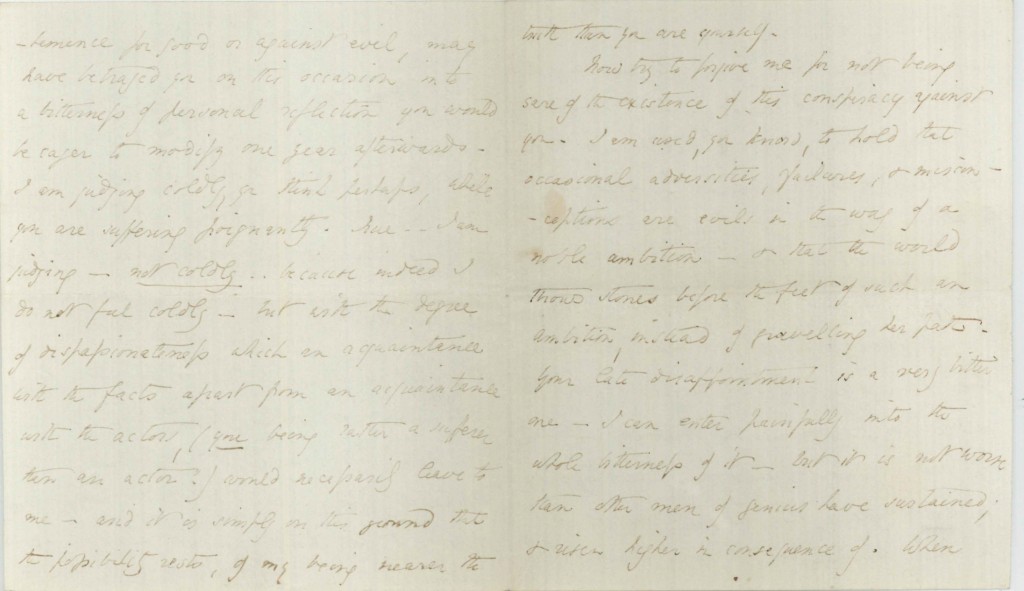

![George MacDonald. Marginalia in Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day: A Poem, by Robert Browning. London: Chapman and Hall, 1850. Page 15. [ABLibrary Rare X821.83 P5 C466c c.13]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-4-1wekpt0-225x300.jpg)

George MacDonald. Marginalia in Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day: A Poem, by Robert Browning. London: Chapman and Hall, 1850. Page 15. [ABLibrary Rare X821.83 P5 C466c c.13]

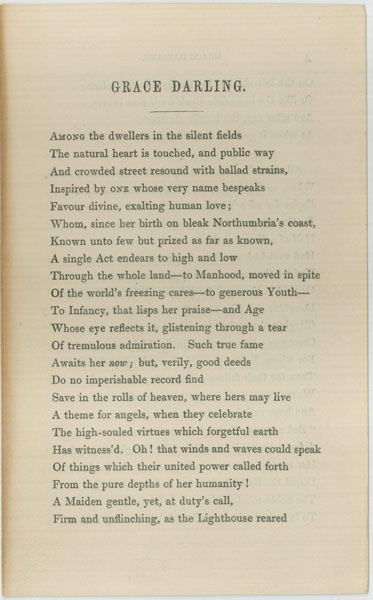

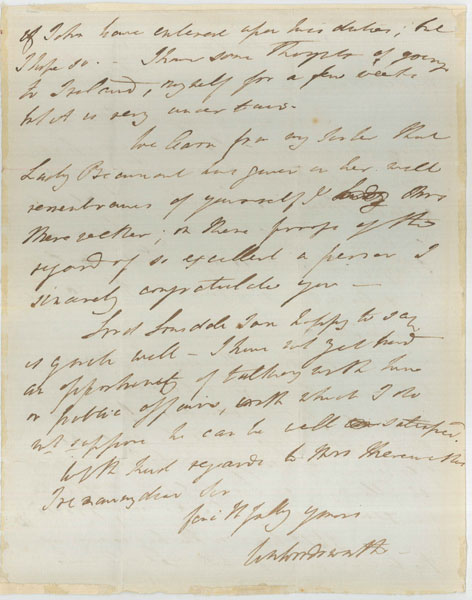

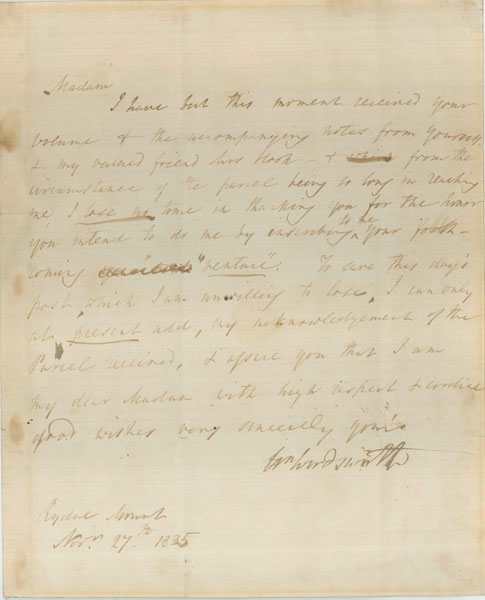

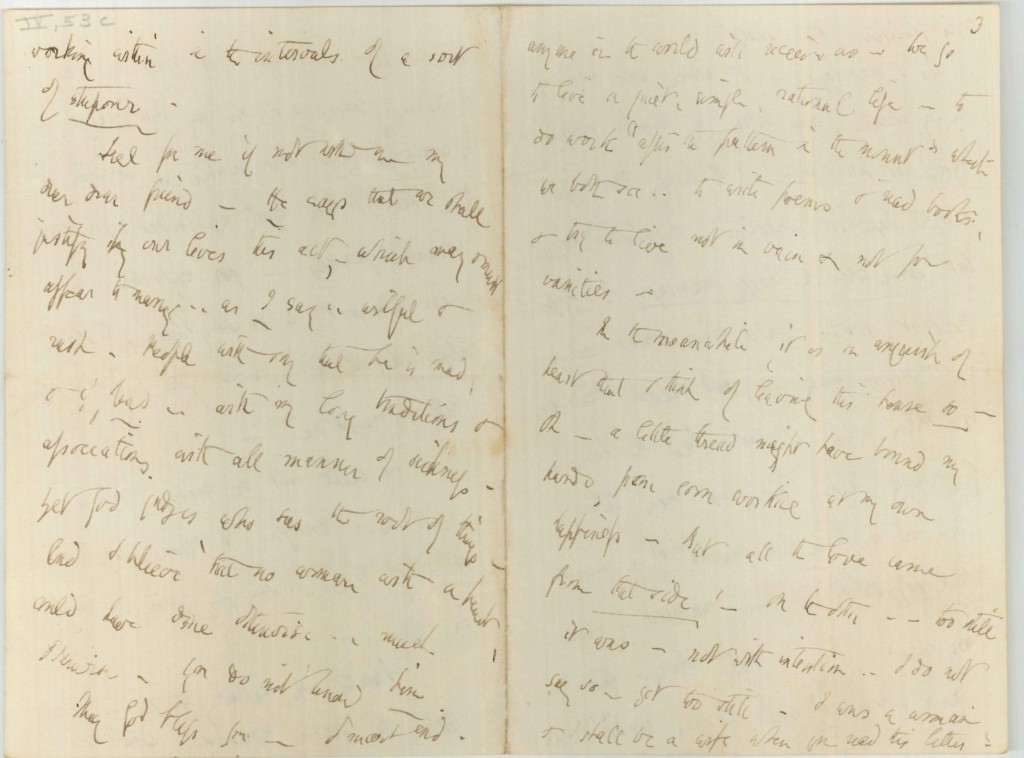

Of further interest to me were the marginal notations in George MacDonald’s first edition of Robert Browning’s Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day (1850), two dramatic monologues that wrestle with the topics raised by the higher criticism. In “Christmas-Eve,” the speaker moves from a satiric rejection of what he regards as a misguided sermon to a sympathetic recognition of all interpretation as imperfect, going on a supernatural night-time journey that takes him from a British dissenting chapel to a Roman catholic church to a German lecture hall—not unlike the journey of Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843). Engaging with this comic yet thoughtful poem at the level of both sound and sense, MacDonald indicates stressed and unstressed syllables in select lines and writes “remark” or “remarks” in the margins of key passages. These notes lay the foundation for MacDonald’s review of this poem in The Monthly Christian Spectator (May 1853), as well as for the lectures he gave on Browning in subsequent decades.

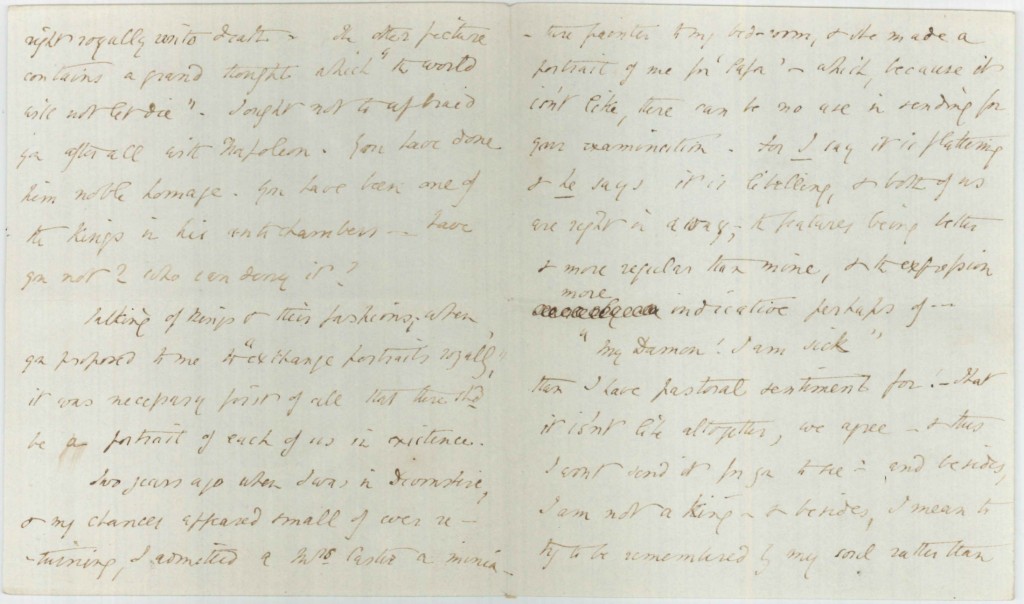

![Robert Browning. Marginalia in Sartor Resartus, by Thomas Carlyle. Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1837. Page 72. [ABLibrary Brownings’ Library X BL 824.8 C286s 1837]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-5-1zhpfd5-225x300.jpg)

Robert Browning. Marginalia in Sartor Resartus, by Thomas Carlyle. Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1837. Page 72. [ABLibrary Brownings’ Library X BL 824.8 C286s 1837]

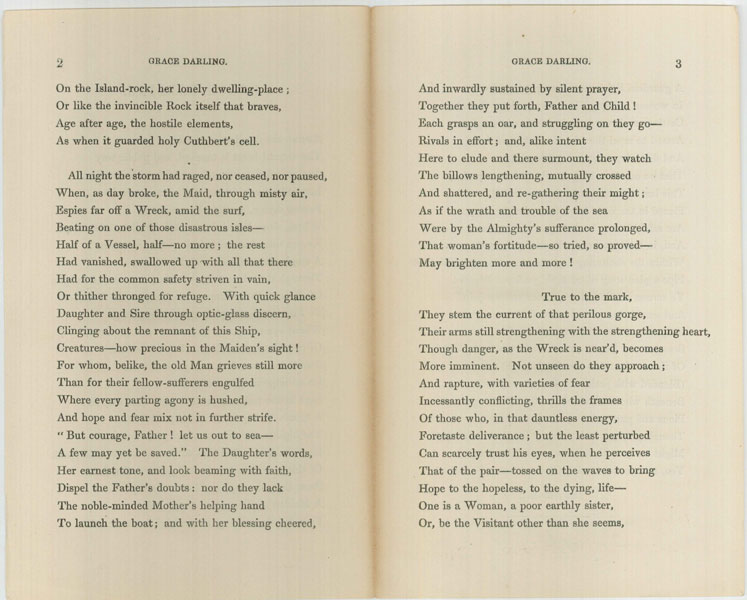

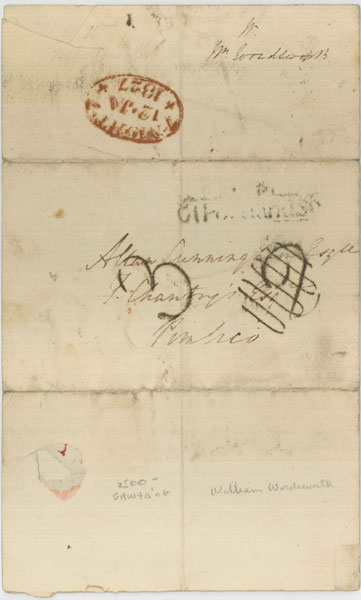

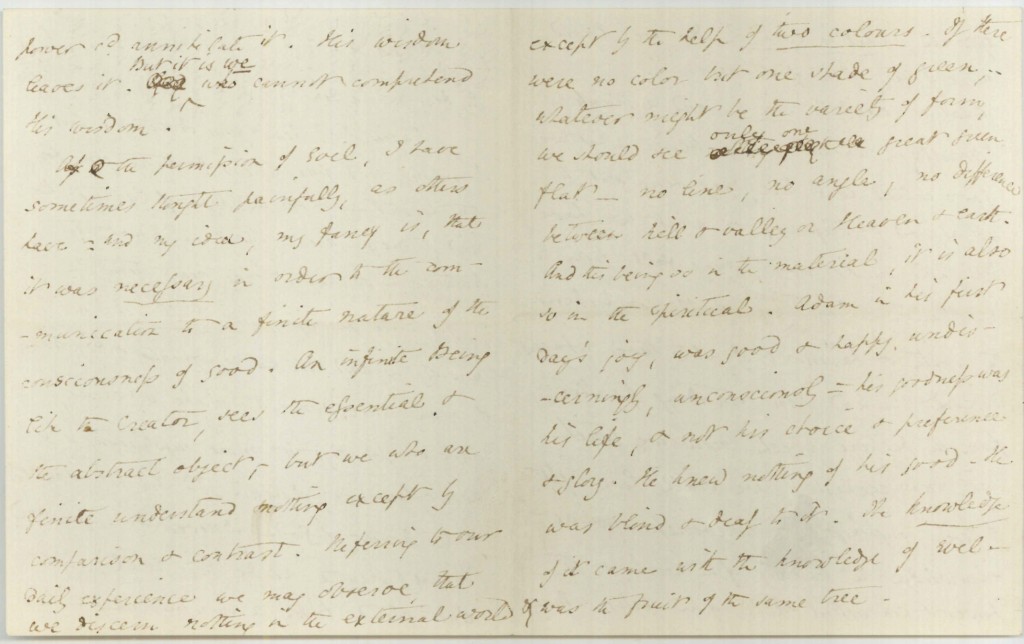

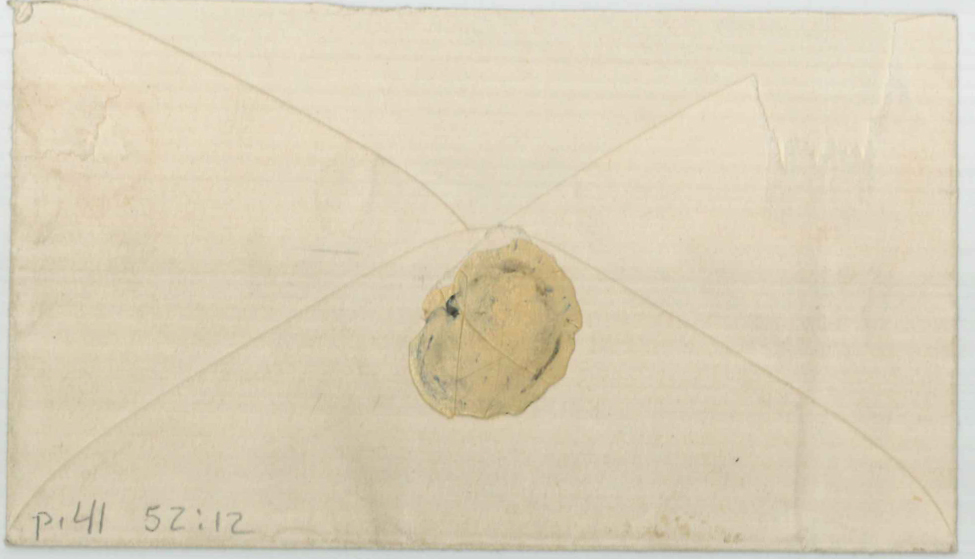

Browning’s own influences can be seen in his copy of the 1837 edition of Thomas Carlyle’s experimental prose essay Sartor Resartus. This densely allusive text emphasizes the challenge of interpretation, as Carlyle adopts the metafictional guise of an English editor translating the work of a German professor. In addition to tracking some of Carlyle’s references to writers such as Jonathan Swift or William Shakespeare, Browning’s notes thicken the book’s intertextual dialogue. In a chapter where Carlyle discusses wonder with reference to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1796), Browning writes, “In wonder all knowledge begins – in wonder it ends & admiration fills up the interspace. But the first wonder is the child of ignorance – the last is the parent of admiration – the first is the birth-throe of knowledge: the last its culmination & apotheosis.” These sentences paraphrase Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s words in a passage from Aids to Reflection (1829), a collection of aphorisms that quote from and comment on various theologians and philosophers in what amounts to a Victorian equivalent to the book of Proverbs. Here, Browning comments on Carlyle’s reflections on Goethe by evoking Coleridge (who, in turn, develops arguments from Aristotle’s Metaphysics) . . . and so on.

These examples are just few of the gems held at the ABL. Other items that I had the chance to look at included pages of EBB’s unpublished girlhood writings that show the growth of her literary ambitions, as well as a notebook of additional manuscript material from the 1840s containing drafts of poems that vary in interesting ways from her published pieces. The rare books collection at the ABL features two illustrated versions of MacDonald’s Phantastes (1858), his first fairy tale for an adult audience: one set of illustrations by John Bell (1894) and the other by Arthur Hughes (1905), each of which offer very different visual interpretations of this story. The library also holds MacDonald’s copy of Coleridge’s Aids to Reflection, which shows evidence of longstanding and affectionate use: the inside cover has the bookplate of MacDonald’s son, while other front matter bears the signature of MacDonald’s father, as well as what appears to be an unpublished sonnet from George MacDonald dated 5 November 1847 and addressed to Louisa Powell, whom he married on 8 March 1851. (My thanks go to manuscript specialist Melinda Creech for helping me to identify this handwriting).

As a result of my time at the ABL, I have not only uncovered additional content for my dissertation but also deepened the way that I understand this content. In addition to informing my current research, the materials here have provided me with ideas for further study that I hope to pursue at a later date. My experience was made all the more enriching by the hospitality of the ABL faculty and staff, who made me feel welcome and generously shared their expertise with me in the kind of conversations that are the very best part of intellectual inquiry.

![Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Manuscript of A Drama of Exile. Page 25. [D0216]](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2018/04/Figure-2-v0mlin-225x300.jpg)