By Michael Milburn, Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

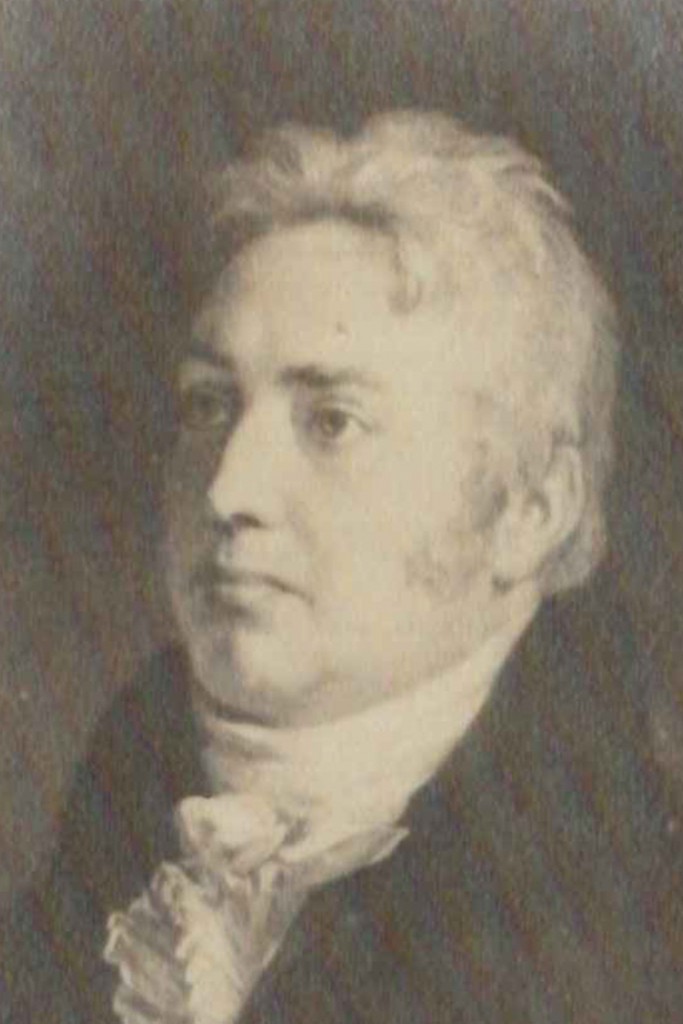

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a first-generation Romantic best known for his poetry and literary criticism, also wrote widely on the subjects of theology, philosophy, science, and politics, in spite of his in part self-made reputation as an opium addict who failed to live up to his potential. He is renowned for such classics as “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” “Christabel,” and “Kubla Khan.”

The ABL has ten letters by Coleridge, eight of which are addressed to his brother George, several first editions, two annotated volumes, and over ninety other books which belonged to members of his family, primarily his descendants.

Draft or Copy of a Letter from George Coleridge to Samuel Taylor Coleridge. [10 March 1798].

Coleridge and his brother George disagreed over Britain’s military actions against the revolutionary government in France. George, who was in favor of the British, wrote this letter in order to extend his hospitality to Coleridge despite their political differences.

We may forget that we are not political Brothers, and call to our Mind, that to philosophize on Government and to legislate are the Duty of a few, to cultivate domestic affections of all.

The lack of signature, however, indicates that unless the document was a transcript, this version of the text, at least, remained an unsent draft.

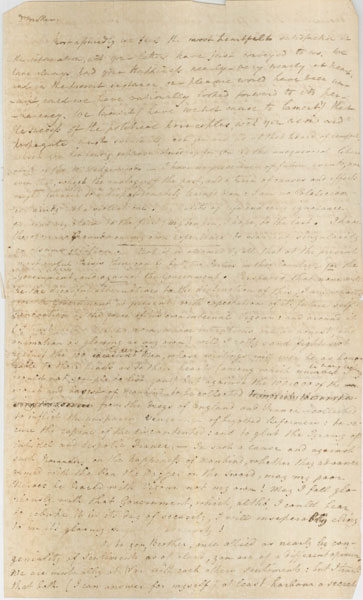

Autograph draft manuscript of Hints respecting Beauty

Letter from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to [Mary Russell Mitford]. [8 July 1811].

In this draft of a letter to Mary Russell Mitford, Coleridge developed some of the aesthetic ideas that would become famous in his “Essays on the Principles of Genial Criticism” and Biographia Literaria. After noting the errors that can arise from using words merely to express degree, he defines beauty in kind as “the reconciliation of ‘the many’ with ‘the one,’” offering the simple example of a triangle, in which three sides are reconciled into a single shape, and the ideal example of a circle, in which radii of many angles are brought together by the one center on which they converge.

Letter from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to George Coleridge. 2 October 1803.

Coleridge experienced night terrors all his adult life, probably worsened by his addiction to opium and the periods of withdrawal when he would try to quit. In this letter, he tells his brother that when he tries to sleep, “such a Host of Horrors rush in—that three nights out of four I fall asleep struggling to lie awake, and start up & bless my own loud screams, that have awakened me.” He had described the experience poetically in “The Pains of Sleep,” written during the previous month, though not published until 1816.

Coleridge’s first volume of poetry

Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Poems on Various Subjects. London, Bristol: G. G. and J. Robinsons; J. Cottle, 1796.

Note the contemporary full tree calf binding, a technique in which the leather was stained to create a pattern resembling a tree.

Percy Bysshe Shelley. Queen Mab. London: Printed and published by W. Clark, 1821.

In a note on his own poem, Percy Bysshe Shelley, a second-generation Romantic writer, advocates for a vegetarian diet as the most expedient solution to the problems facing humanity, whether medical or moral, decrying in particular “the brutal pleasures of the chase.” Coleridge could not resist the opportunity to let the wind out of Shelley’s sails by writing in the margin, “Mr. Shelley’s favourite diversion at present (1822) is hunting.”

The comment is not in Coleridge’s collected marginalia.

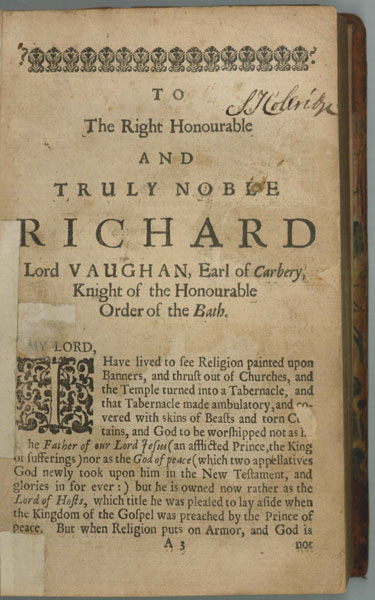

Jeremy Taylor. The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living …: Together With Prayers Containing the Whole Duty of a Christian. The eleventh ed. London: Printed by Roger Norton for Richard Royston, 1676.

This volume by the seventeenth-century divine Bishop Jeremy Taylor belonged to Coleridge and contains a brief marginal note by him.  Coleridge’s son Hartley, a poet in his own right, inscribed the copy in order to remind himself of his father’s legacy: “Hartley Coleridge / a small but precious / portion / of his promised inheritance.”

Coleridge’s son Hartley, a poet in his own right, inscribed the copy in order to remind himself of his father’s legacy: “Hartley Coleridge / a small but precious / portion / of his promised inheritance.”

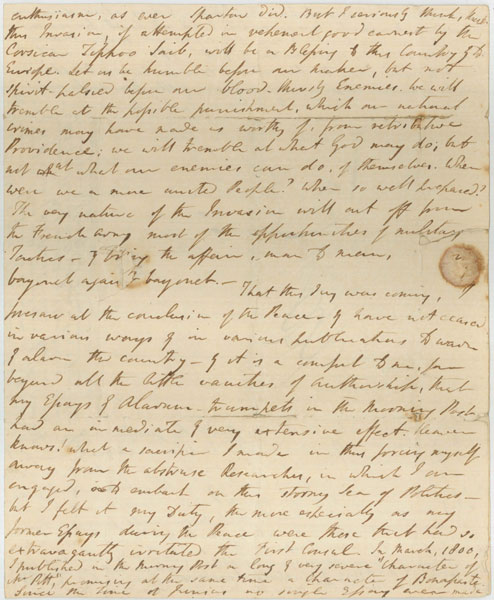

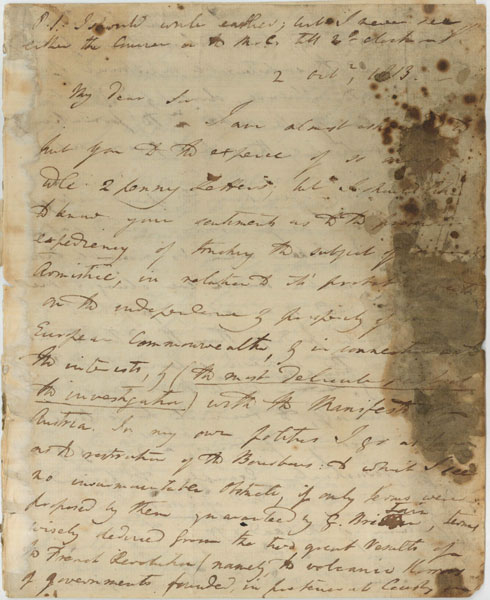

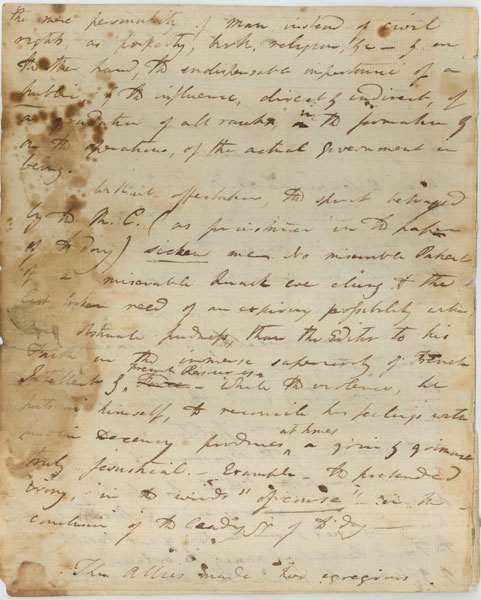

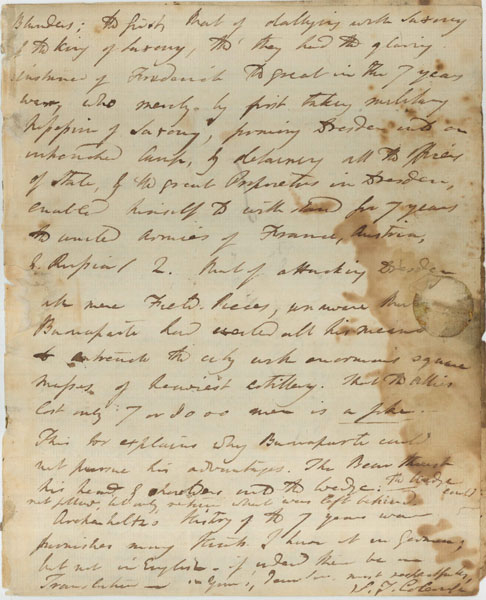

Letter from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to T. G. Street.

2 October 1813.

Coleridge wrote to Street, the editor of the Courier, to complain of the Morning Chronicle’s coverage of the Napoleonic Wars. On this page, Coleridge refers to “the volcanic” Horrors of the French Revolution. The letter has yet to be published.