When Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), abolitionist and author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, visited the White House in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln purportedly welcomed her by saying, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this Great War!” But Stowe was not alone. As the Baylor University Libraries observe the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War by mounting exhibits under the overarching theme “with charity for all,” taken from President Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, the Armstrong Browning Library’s exhibit Imagining Charity for All highlights works by some of the men and women who, like Stowe, used their literary talent to promote freedom and equality. The items on display from the collection of the Armstrong Browning Library represent a small, but powerful, portion of the large body of anti-slavery writings produced prior to and during the Civil War that furthered the cause of ending slavery.

When Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), abolitionist and author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, visited the White House in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln purportedly welcomed her by saying, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this Great War!” But Stowe was not alone. As the Baylor University Libraries observe the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War by mounting exhibits under the overarching theme “with charity for all,” taken from President Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, the Armstrong Browning Library’s exhibit Imagining Charity for All highlights works by some of the men and women who, like Stowe, used their literary talent to promote freedom and equality. The items on display from the collection of the Armstrong Browning Library represent a small, but powerful, portion of the large body of anti-slavery writings produced prior to and during the Civil War that furthered the cause of ending slavery.

Imagining Charity for All is on display in the Hankamer Treasure Room of the Armstrong Browning Library through June 1, 2015. Items on display can also be viewed below.

***

Harriet Beecher Stowe

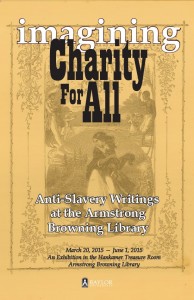

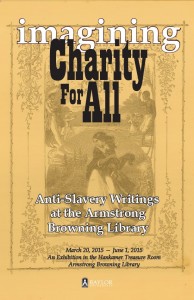

Harriet Beecher Stowe. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. London: J. Cassell, 1852.

Harriet Beecher Stowe. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. London: J. Cassell, 1852.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-known work Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which originally appeared in serial format in the weekly newspaper The National Era from 5 June 1851 to 1 April 1852, became an immediate bestseller when it was published in Boston as a book in two volumes in 1852. The anti-slavery novel sold 300,000 copies in the United States and 1.5 million copies in Great Britain in its first year of publication and was translated into over 60 languages. This London edition was published the same year in one volume, with illustrations by George Cruikshank. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS2954 .U5 1852]

***

***

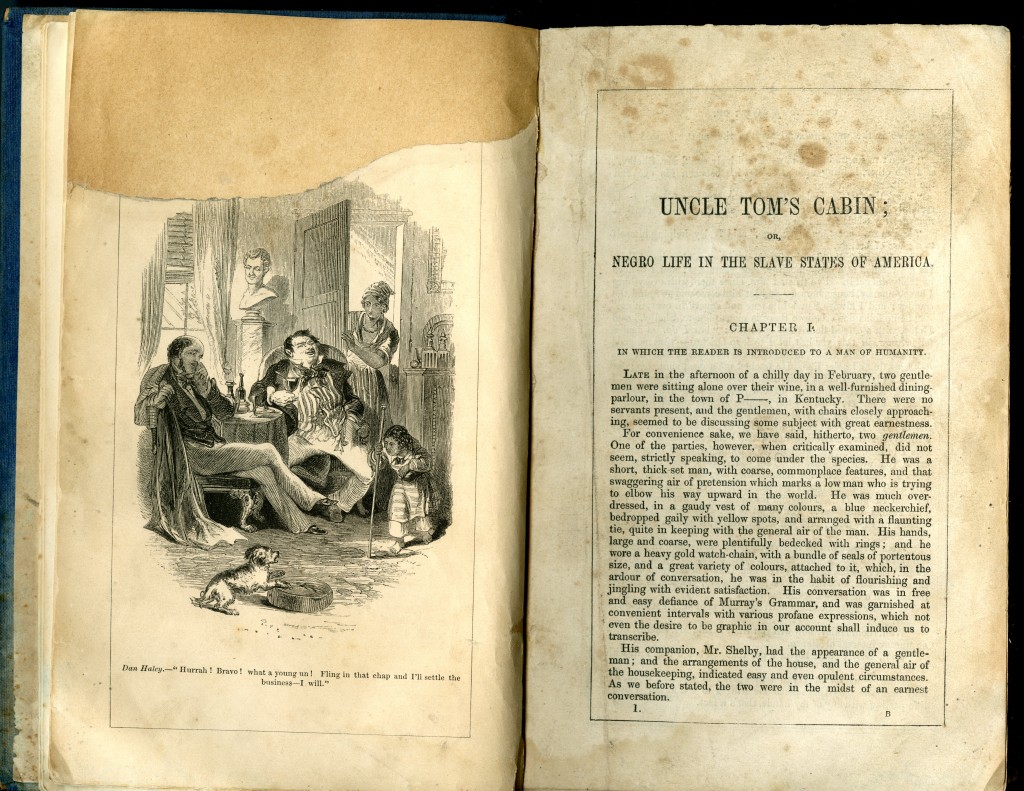

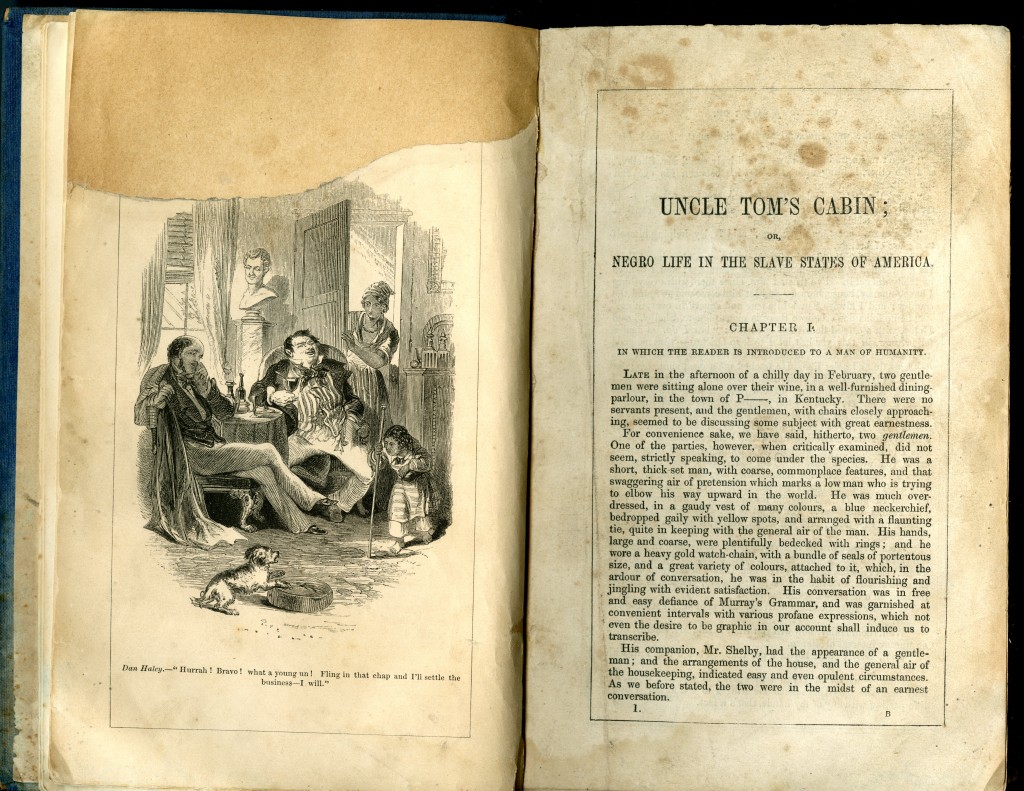

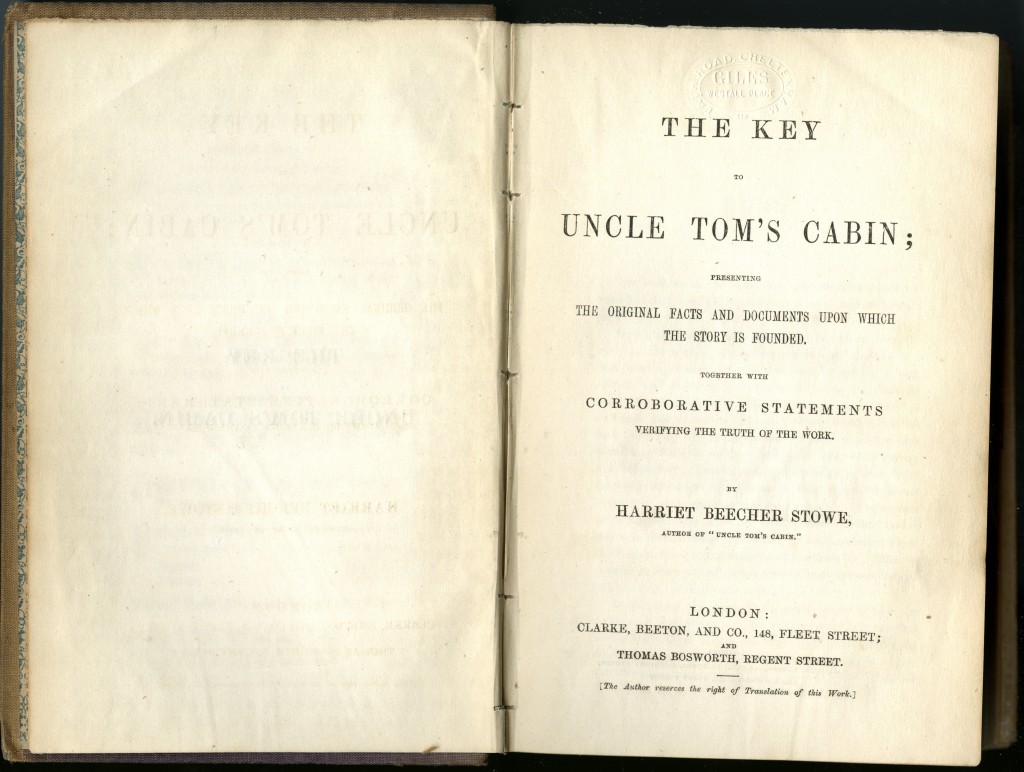

Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin; Presenting the Original Facts and Documents Upon Which the Story Is Founded. Together with Corroborative Statements Verifying the Truth of the Work. London: Clarke, Beeton, and Co., 148 Fleet Street; and Thomas Bosworth, Regent Street, [1853].

Responding to critics who challenged her depiction of slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe published The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1853, which contained documentary evidence in the form of newspaper accounts and legal proceedings to support the claims she made in her novel. [ABLibrary 19thCent E449 .S896 1850z]

***

***

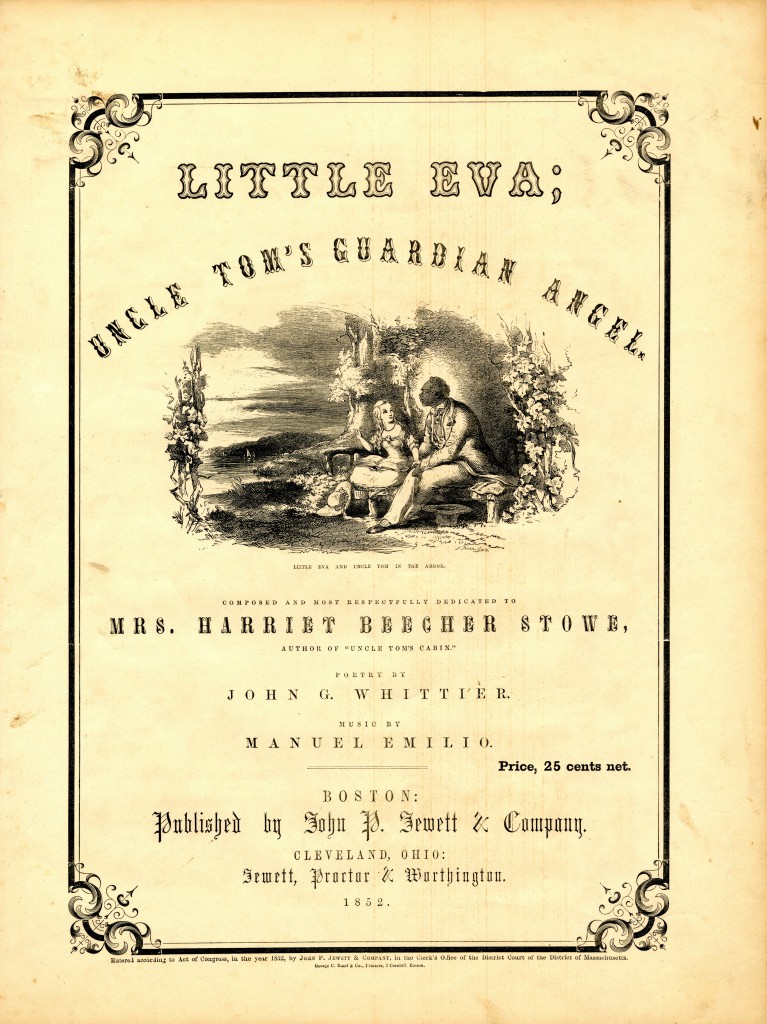

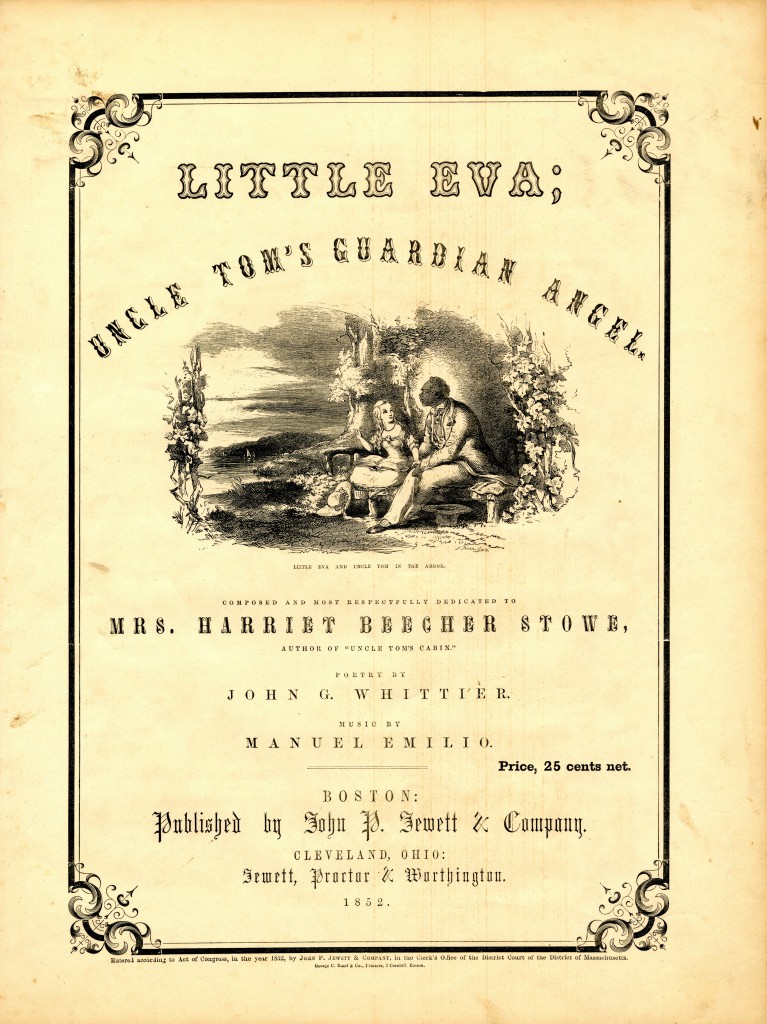

Little Eva; Uncle Tom’s Guardian Angel. Composed and Most Respectfully Dedicated to Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Poetry by John G. Whittier. Music by Manual Emilio. Boston: Published by John P. Jewett & Company; Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor & Worthington, 1852.

As part of his efforts to increase the circulation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe’s American publisher John P. Jewett commissioned John Greenleaf Whittier to write a poem about the novel’s young abolitionist character Little Eva. The poem, which first appeared in the anti-slavery newspaper The Independent, was set to music by Manuel Emilio. [ABLibrary 19thCent Jumbo M1619.5.E45x L5 1852]

***

***

[Harriet Beecher Stowe]. Pictures and Stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Boston: Published by John P. Jewett & Co., [1853].

This version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published by John P. Jewett as part of his Juvenile Anti-Slavery Toy Books series, was “designed to adapt Mrs. Stowe’s touching narrative to the understandings of the youngest readers and to foster in their hearts a generous sympathy for the wronged negro race of America.” [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ PS2854 .U5 1853c]

The last page of Picture and Stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which includes John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “Little Eva Song. Uncle Tom’s Guardian Angel,” printed with music.

The last page of Picture and Stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which includes John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “Little Eva Song. Uncle Tom’s Guardian Angel,” printed with music.

***

***

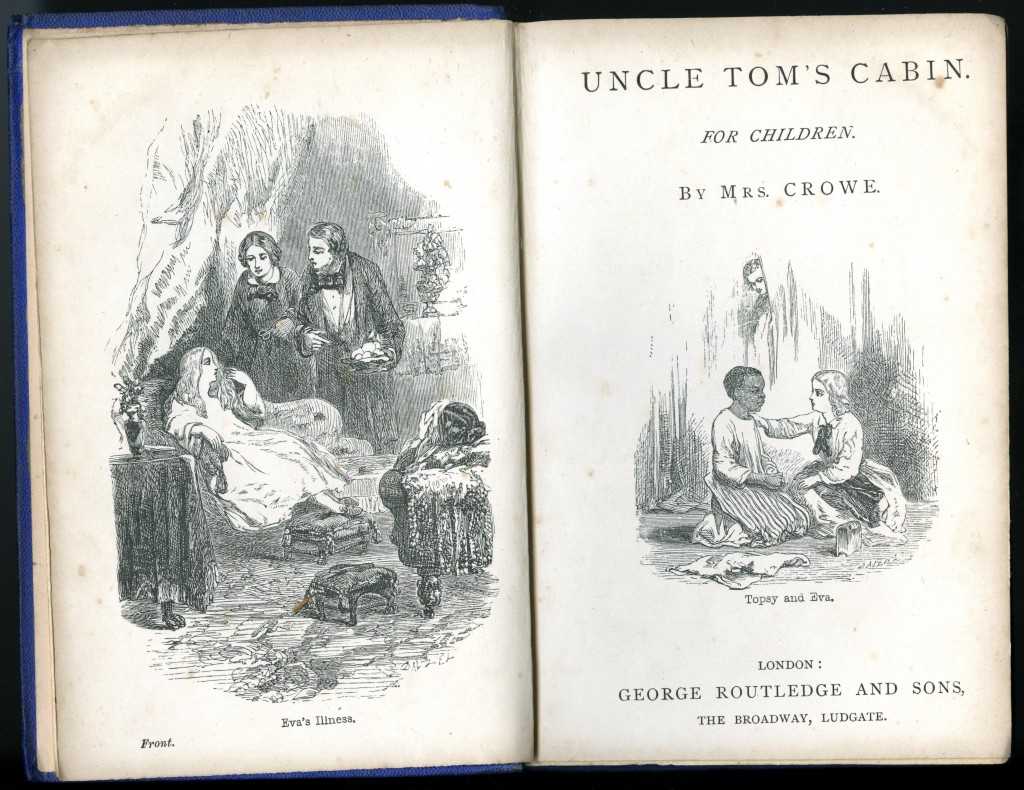

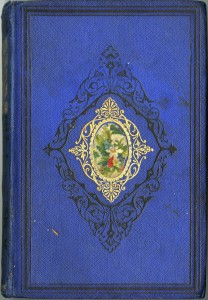

Catherine Crowe. Uncle Tom’s Cabin for Children. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1867.

Catherine Crowe. Uncle Tom’s Cabin for Children. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1867.

This version of Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was adapted for children by Catherine Crowe (1790–1872), an English writer best known for her novels, including The Adventures of Susan Hopley, or, Circumstantial Evidence (1841), The Story of Lilly Dawson (1847), and The Night Side of Nature, or, Ghosts and Ghost Seers (1848). [ABLibrary Offices]

***

***

Harriet Beecher Stowe. Dred; A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp [2 vols.]. Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Company, 1856.

Harriet Beecher Stowe. Dred; A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp [2 vols.]. Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Company, 1856.

Stowe wrote her second anti-slavery novel Dred in response to the violence that broke out between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces in Kansas following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed white male settlers in those territories to determine through popular sovereignty whether they would allow slavery within each territory. The novel was popular, selling over 100,000 copies in its first month of publication. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS2954 .D7 1856 v.1-2]

***

John Greenleaf Whittier

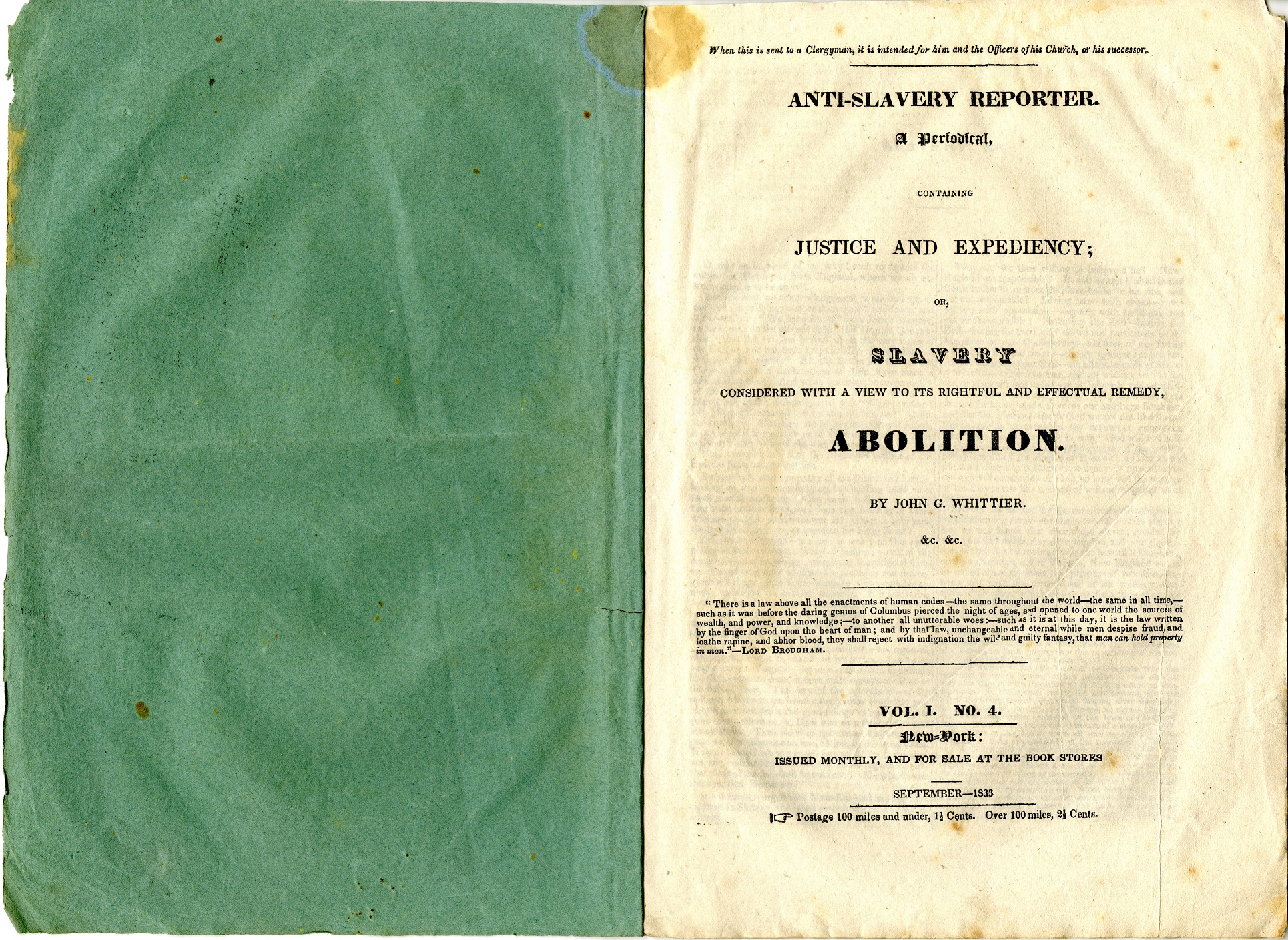

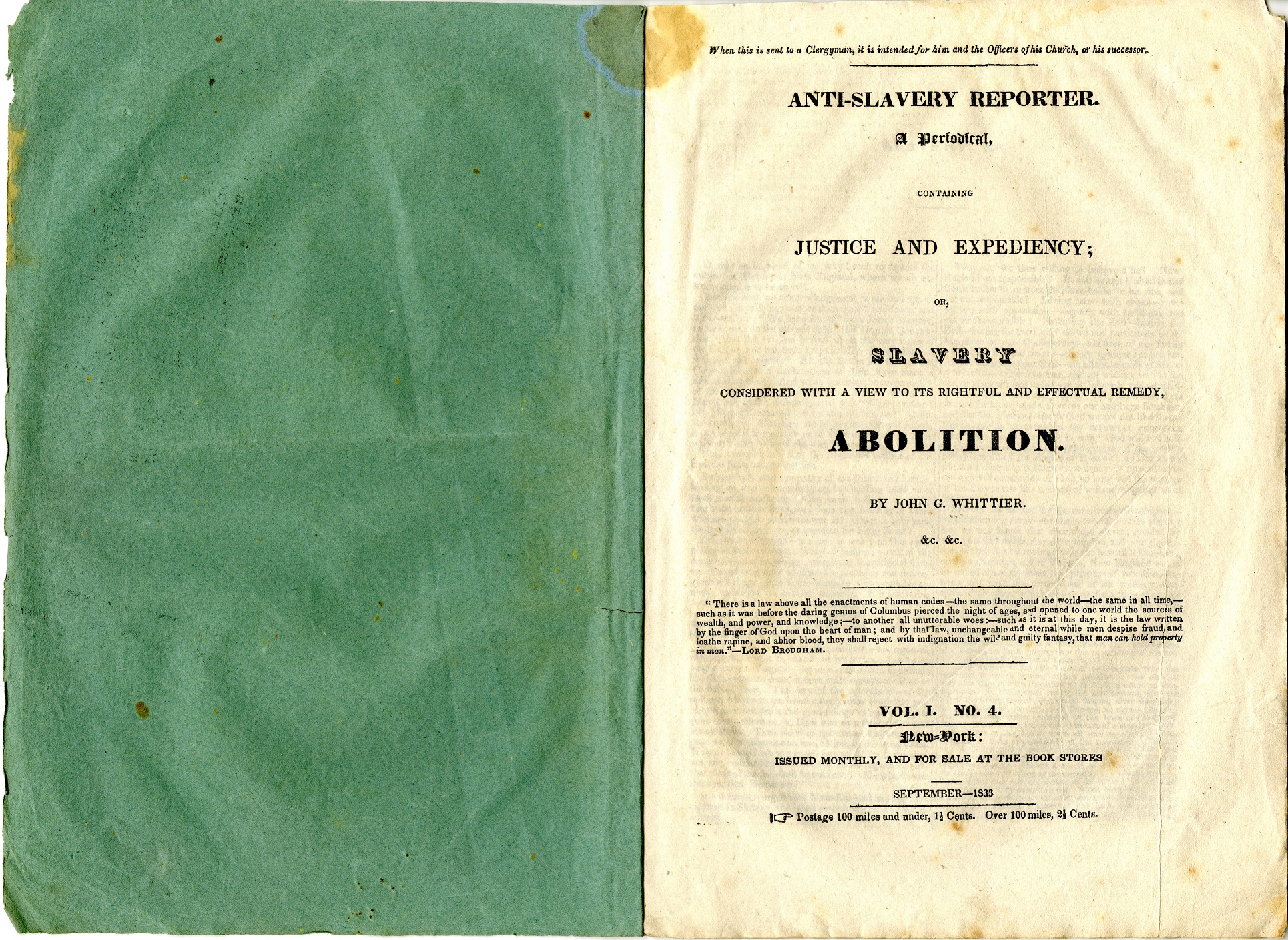

John Greenleaf Whittier. Anti-Slavery Reporter. A Periodical, Containing Justice and Expediency; or, Slavery Considered with a View to Its Rightful and Effectual Remedy, Abolition. Vol. 1, No. 4. New York: Issued monthly, and for sale at the book stores, September, 1833.

John Greenleaf Whittier. Anti-Slavery Reporter. A Periodical, Containing Justice and Expediency; or, Slavery Considered with a View to Its Rightful and Effectual Remedy, Abolition. Vol. 1, No. 4. New York: Issued monthly, and for sale at the book stores, September, 1833.

John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) was a Quaker, a popular American poet, and a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. In this pamphlet published in 1833, he called for the immediate and unconditional emancipation of slaves. With 5,000 copies printed and distributed for free by abolitionist Arthur Tappan, this appeal publicly aligned Whittier with the anti-slavery cause and made him a leading figure of the abolitionist movement. [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ HT1031 .W54x 1833]

***

***

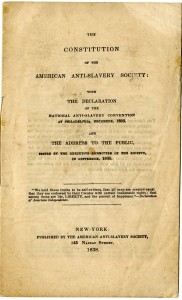

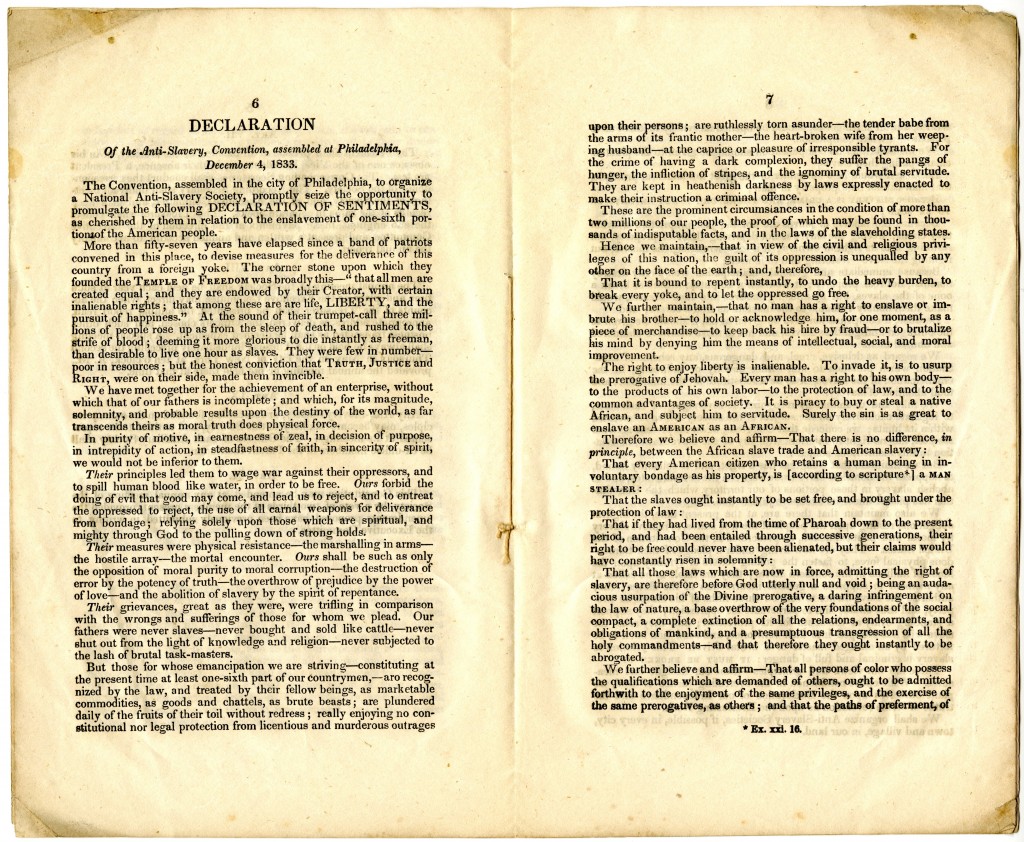

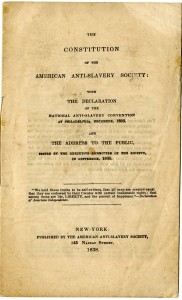

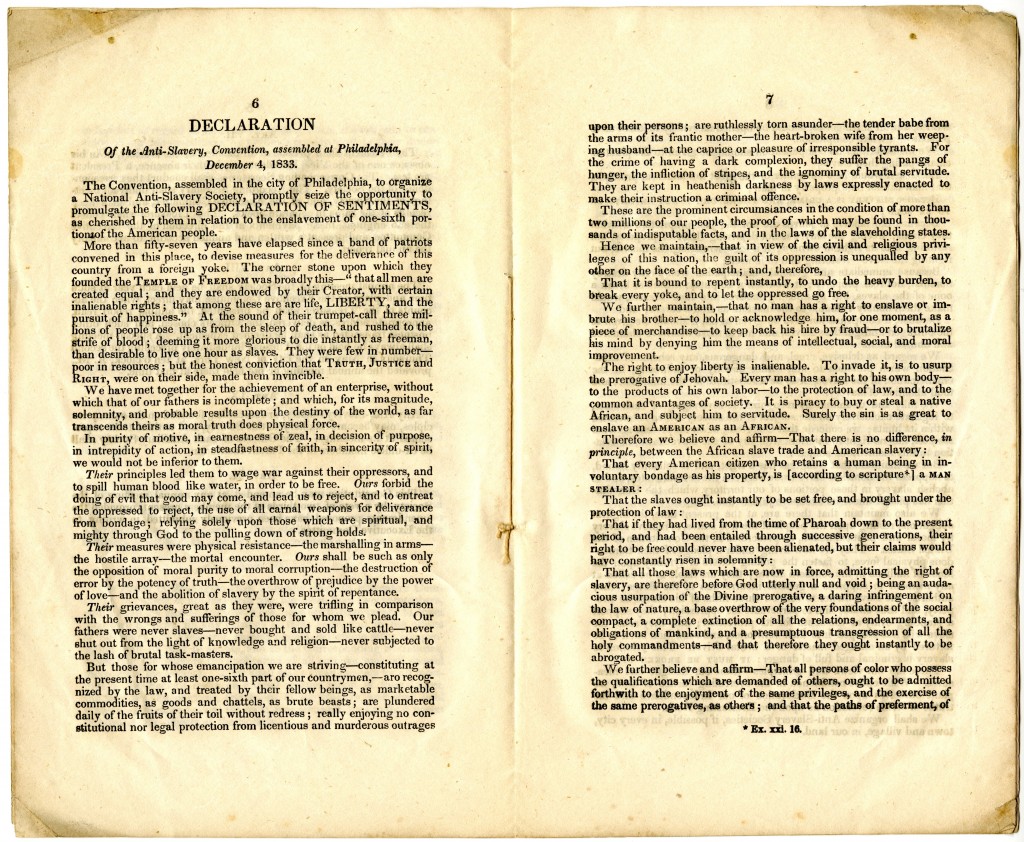

The Constitution of the American Anti-Slavery Society: with the Declaration of the National Anti-Slavery Convention at Philadelphia, December 1833, and the Address to the Public, Issued by the Executive Committee of the Society, in September 1835. New York: Published by the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1838.

The Constitution of the American Anti-Slavery Society: with the Declaration of the National Anti-Slavery Convention at Philadelphia, December 1833, and the Address to the Public, Issued by the Executive Committee of the Society, in September 1835. New York: Published by the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1838.

Whittier signed the Declaration of the National Anti-Slavery Convention in 1833, an action he considered more important than any of his literary achievements. The Anti-Slavery Declaration is reprinted in this pamphlet along with the Constitution of the American Anti-Slavery Society. [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ HT853 .A53x 1838]

***

***

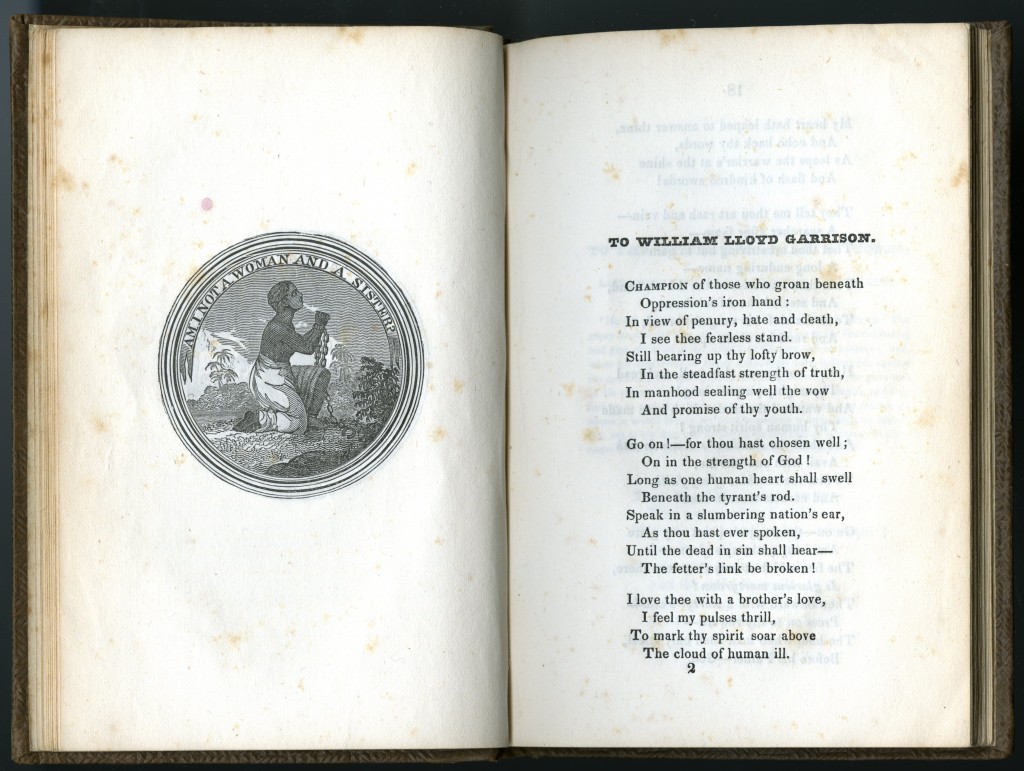

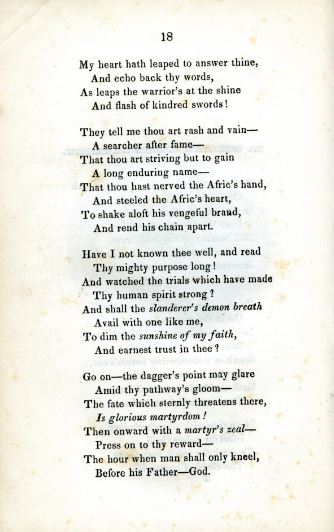

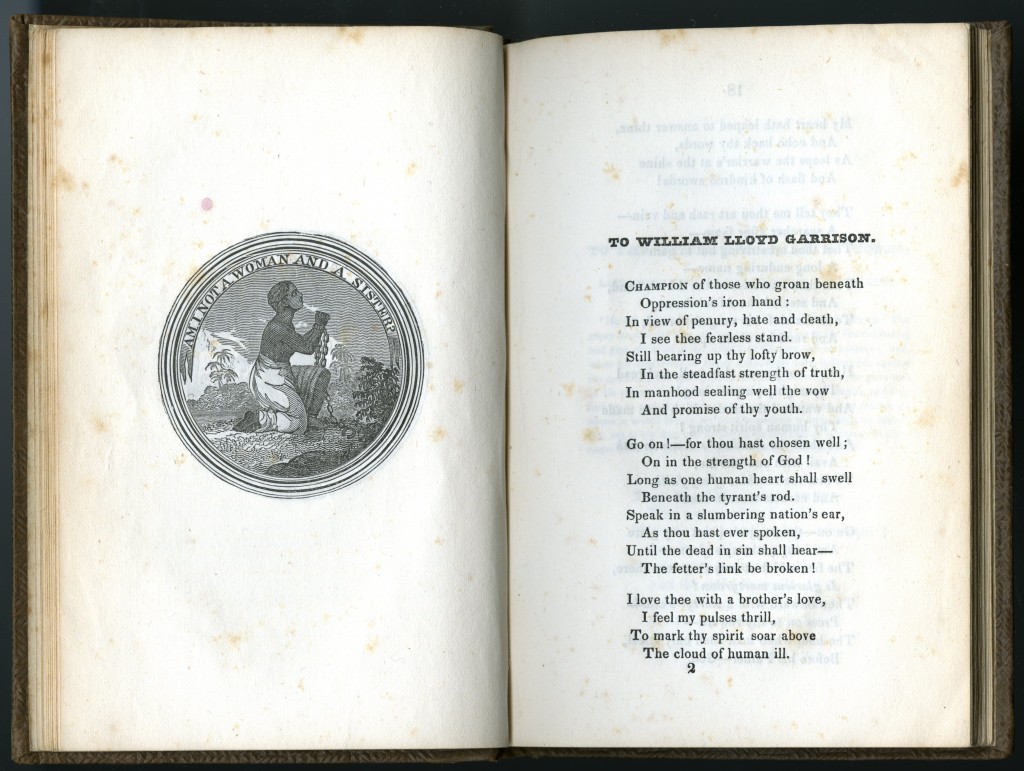

John Greenleaf Whittier. Poems Written During the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States, Between the Years 1830 and 1838. Boston: Published by Isaac Knapp, 1837.

Whittier’s anti-slavery poems, which appeared in various periodicals during the 1830s, were published collectively in this volume in 1837 by Isaac Knapp, publisher of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. The volume begins with a tribute to William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), a prominent abolitionist, editor of The Liberator, and a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS3250 .E37a]

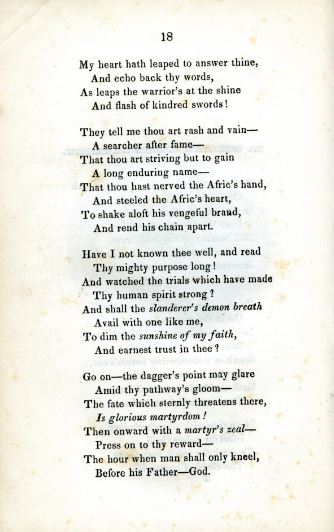

The conclusion of Whittier’s poem “To William Lloyd Garrison.”

The conclusion of Whittier’s poem “To William Lloyd Garrison.”

***

***

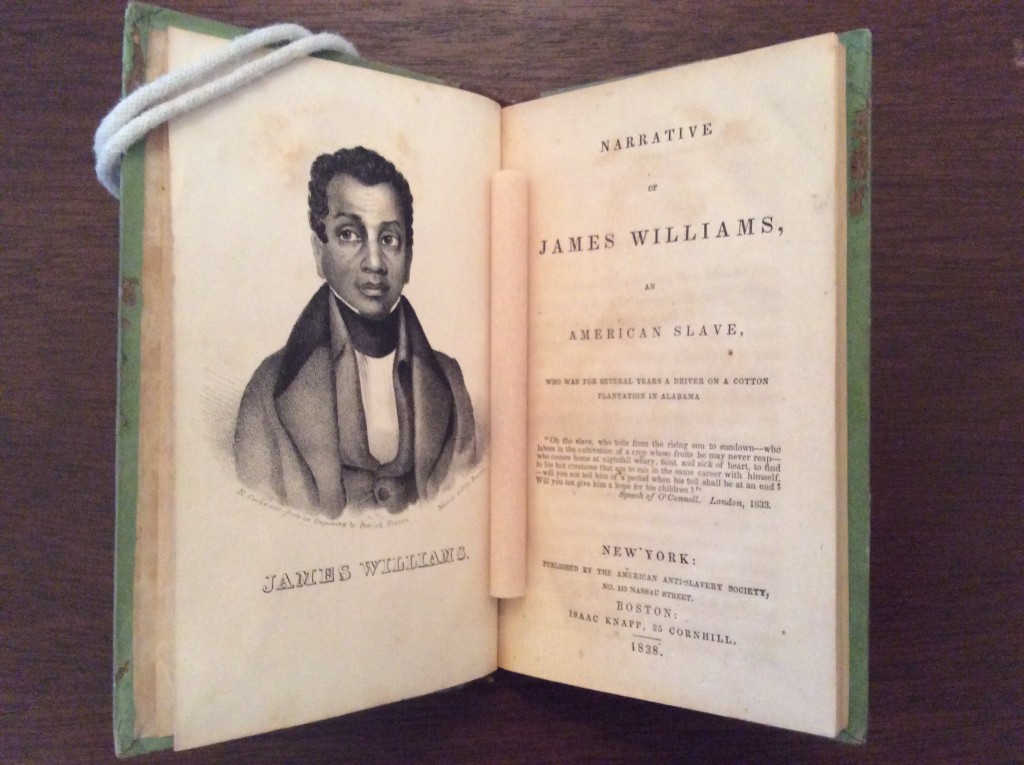

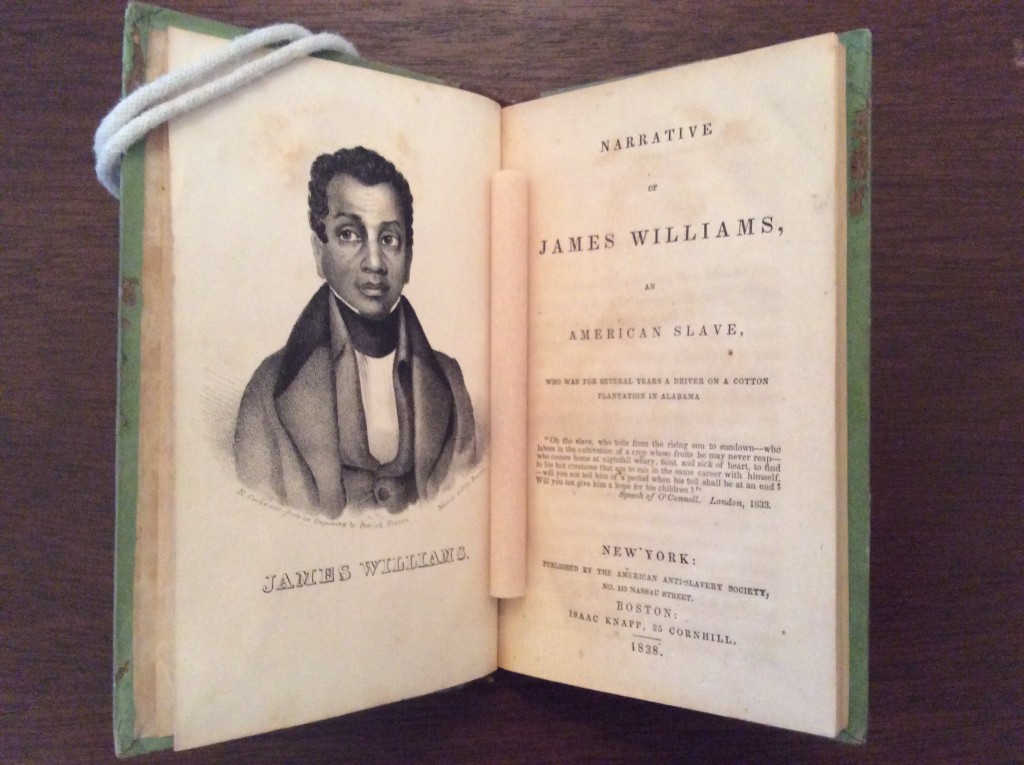

Narrative of James Williams, an American Slave, Who was for Several Years a Driver on a Cotton Plantation in Alabama. New York: Published by the American Anti-Slavery Society; Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838.

Despite widespread attacks on escaped slave James Williams’s credibility, the American Anti-Slavery Society published this account of Williams’s life as an enslaved man in Virginia and Alabama. John Greenleaf Whittier, who was working as the secretary of the American Anti-Slavery Society at the time, met Williams, heard his story firsthand, and produced the text for this narrative, which he stated in the preface to the published work “presents an unexaggerated picture of slavery as it exists on the cotton plantations of the South and West.” [ABLibrary 19thCent E444 .W743 1838]

***

***

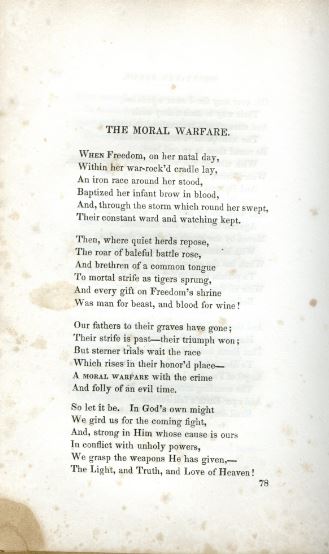

John Greenleaf Whittier. Poems. Philadelphia: Published by Joseph Healy; Boston: Weeks, Jordan & Co.; New York: John S. Taylor, 1838.

This collection of Whittier’s poems was edited by Whittier and published by Joseph Healy, financial agent of the Anti-Slavery Society of Pennsylvania. The volume contains 24 anti-slavery poems and 26 poems on miscellaneous subjects. Whittier placed the following quotation from Samuel Taylor Coleridge on the book’s title page:

“There is a time to keep silence,” saith Solomon; but when I proceeded to the first verse of the fourth chapter of the Ecclesiastes, “and considered all the oppressions that are done under the sun, and beheld the tears of such as were oppressed, and they had no comforter; and on the side of the oppressors there was power;” I concluded this was not the time to keep silence; for Truth should be spoken at all times, but more especially at those times when to speak Truth is dangerous. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS3250 .E38 c.2]

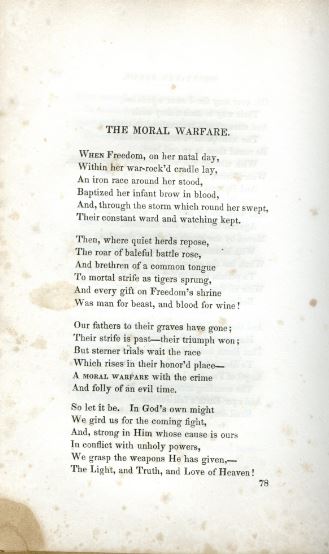

Whittier’s poem “The Moral Warfare” in Poems (1838).

Whittier’s poem “The Moral Warfare” in Poems (1838).

***

***

John Greenleaf Whittier. The Branded Hand. [Salem, Ohio: The Anti-Slavery Bugle, 1845].

Whittier wrote The Branded Hand in response to an event in 1844 in which a tradesman named Jonathan Walker tried to help seven slaves escape by boat from Florida. Walker was caught, tried, convicted in a federal territorial court, and branded with the initials “S.S.” for “slave stealer,” which is depicted on the first page of this tract. Walker was considered a hero by abolitionists and images of his branded hand and literary praises like Whittier’s were widespread. [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ E450 .W17]

***

***

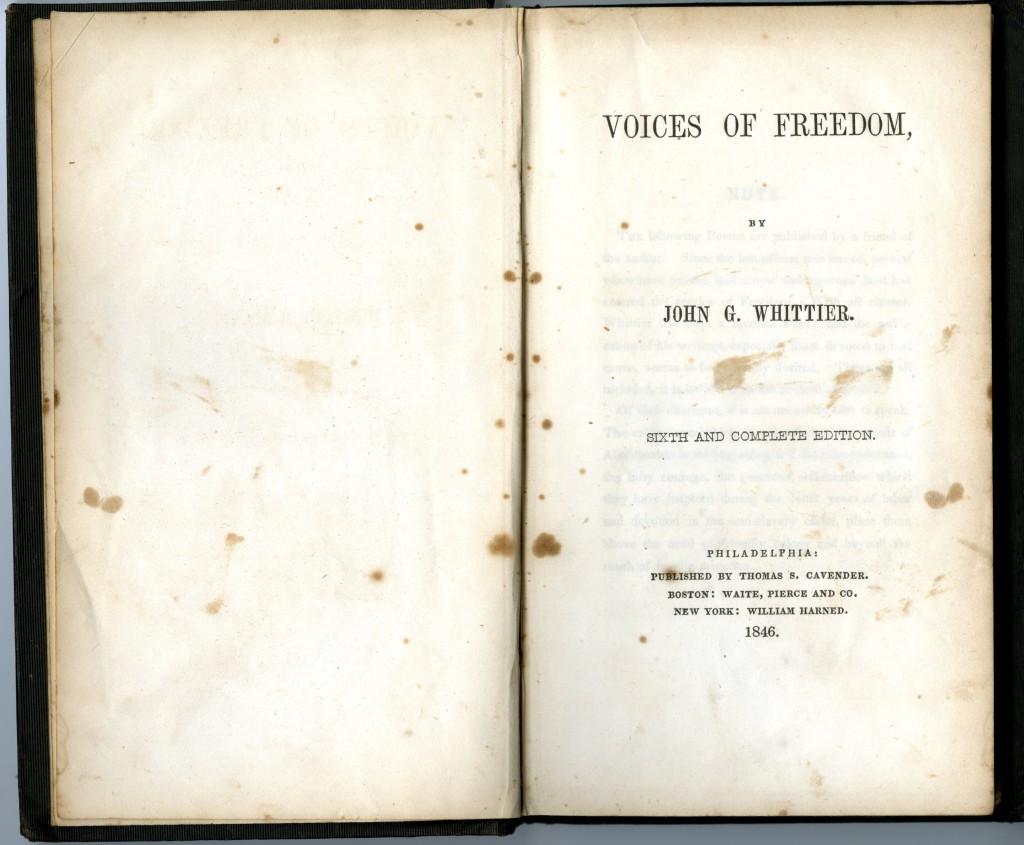

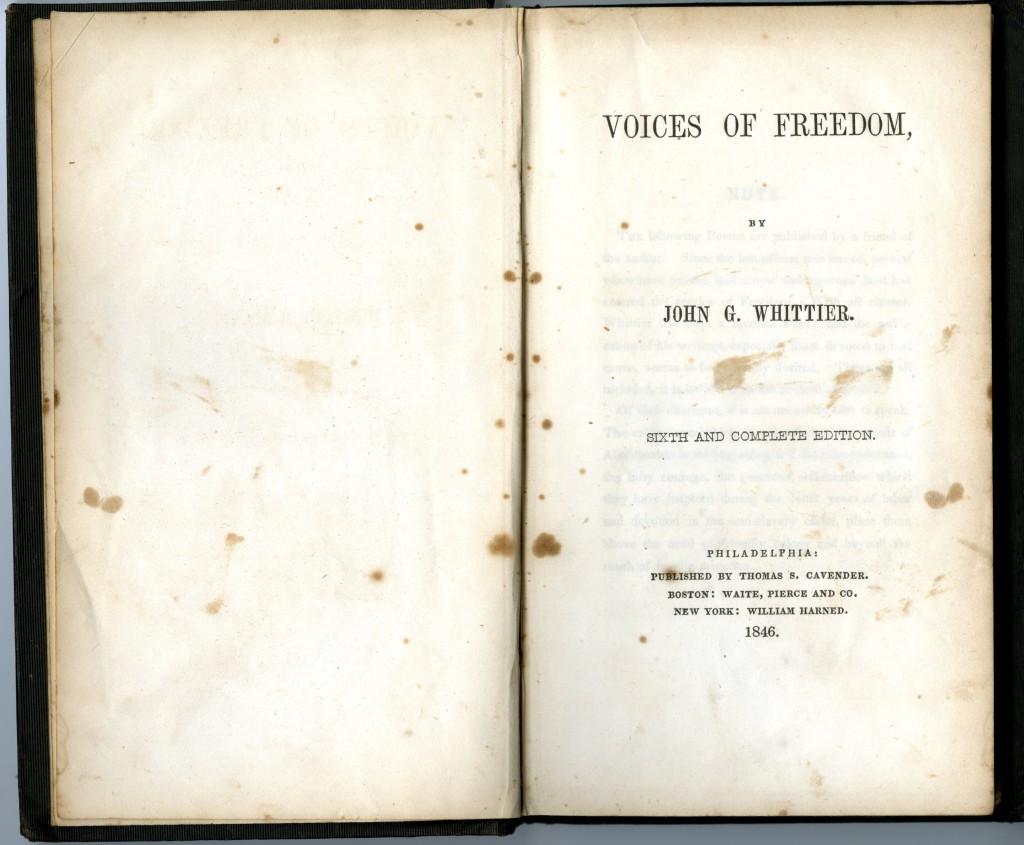

John Greenleaf Whittier. Voices of Freedom. Sixth and Complete Edition. Philadelphia: Published by Thomas S. Cavender; Boston: Waite, Pierce and Co.; New York: William Harned, 1846.

The introductory note to this collection of anti-slavery poems states:

Since the last edition was issued, several years have passed, and a new and vigorous host has entered the service of Freedom. With all classes, Whittier has been a favorite Poet; and the publication of his writings, especially those devoted to that cause, seems to be generally desired. These are all included, it is believed, in the present collection.

[ABLibrary 19thCent PS3269 .V6 1846]

***

***

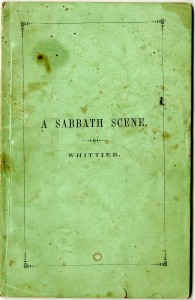

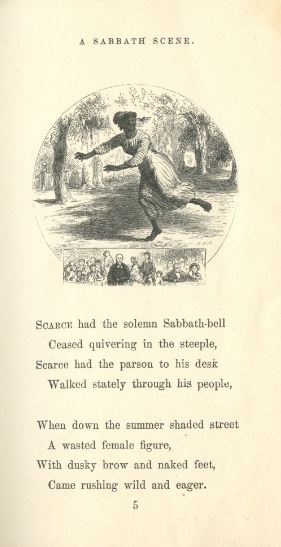

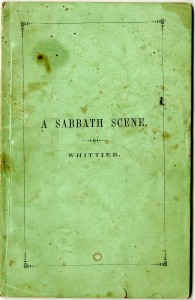

John Greenleaf Whittier. A Sabbath Scene. Boston: John P. Jewett and Company; Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor, and Worthington; London: Sampson, Low, Son and Company, 1854.

John Greenleaf Whittier. A Sabbath Scene. Boston: John P. Jewett and Company; Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor, and Worthington; London: Sampson, Low, Son and Company, 1854.

The headnote to Whittier’s poem “A Sabbath Scene,” appearing in the Riverside Edition of The Writings of John Greenleaf Whittier (1888) reads:

This poem finds its justification in the readiness with which, even in the North, clergymen urged the prompt execution of the Fugitive Slave Law as a Christian duty, and defended the system of slavery as a Bible institution.

Passed by the United States Congress on 18 September 1850, the Fugitive Slave Law required that all escaped slaves be returned to their masters upon capture. Law enforcement officers and citizens in the free states were expected to comply with this law. [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ PS3265 .S2 1854]

The first page of Whittier’s poem “A Sabbath Scene.”

***

***

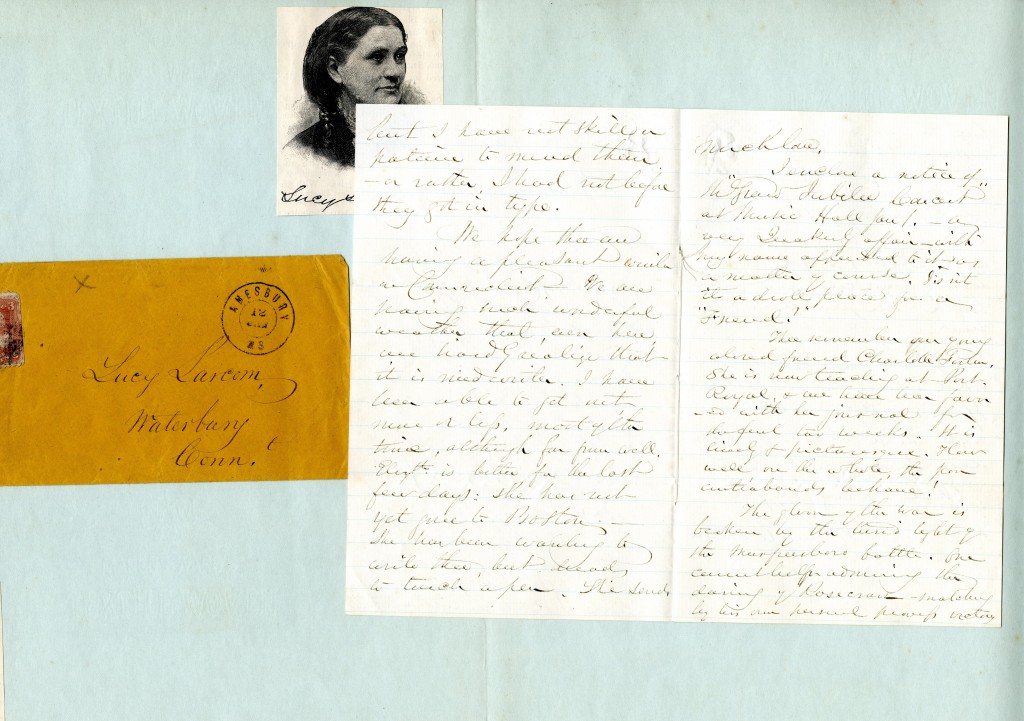

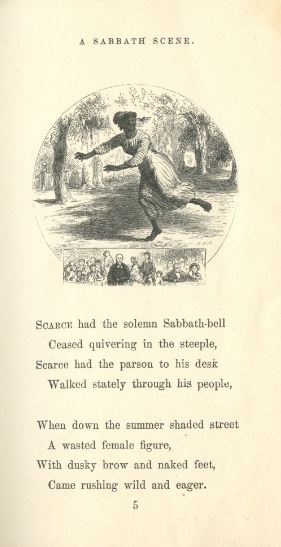

Letter from John Greenleaf Whittier to Lucy Larcom. 10 January 1863.

In this letter to poet Lucy Larcom (1824-1893), Whittier mentions the work of Charlotte Forten (later Grimké, 1837-1914), an African-American anti-slavery activist, poet, and educator, who taught freedmen in the South Carolina Sea Islands in a program known as the Port Royal Experiment. He also reflects on the outcome of the Second Battle of Murfreesboro, which had been fought from 31 December 1862 to 2 January 1863, resulting in Confederate withdrawal from Middle Tennessee.

Whittier writes:

Thee remember our young colored friend Charlotte Forten. She is now teaching at Port Royal, & we have been favored with her journal for the last two weeks. It is lively & picturesque. How well, on the whole, the poor contrabands behave!

The gloom of the war is broken by the lurid light of the Murfeesboro battle. One cannot help admiring the daring of Rosecrans—snatching by his own personal prowess victory from the very jaws of defeat. I shudder to think of the lives that must be sacrificed to open the Mississippi at Vicksburg. Ah me! It is hard to be a Quaker at these times! Yet never was I more convinced of the truth of our principles, than now.

***

***

John Greenleaf Whittier. In War Time and Other Poems. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1864.

Whittier’s poem “At Port Royal,” first published in the Atlantic in 1862 and reprinted in this collection of poems, contains the “Song of the Negro Boatmen,” in which Whittier imagines the singing of the slaves who were freed in the South Carolina Sea Islands after Union forces captured Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861. Written in dialect, the poem became a popular song during the Civil War. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS3259 .I5 1864]

The “Song of the Negro Boatmen” begins:

Oh, praise an’ tanks! De Lord he come

To set de people free;

To set de people free;

An’ massa tink it day ob doom,

An’ we ob jubilee.

De Lord dat heap de Red Sea waves

He jus’ as ‘trong as den;

He say de word: we las’ night slaves;

To-day, de Lord’s freemen.

De yam will grow, de cotton blow,

We’ll hab de rice an’ corn:

Oh, nebber you fear, if nebber you hear

De driver blow his horn!

***

Lydia Huntley Sigourney

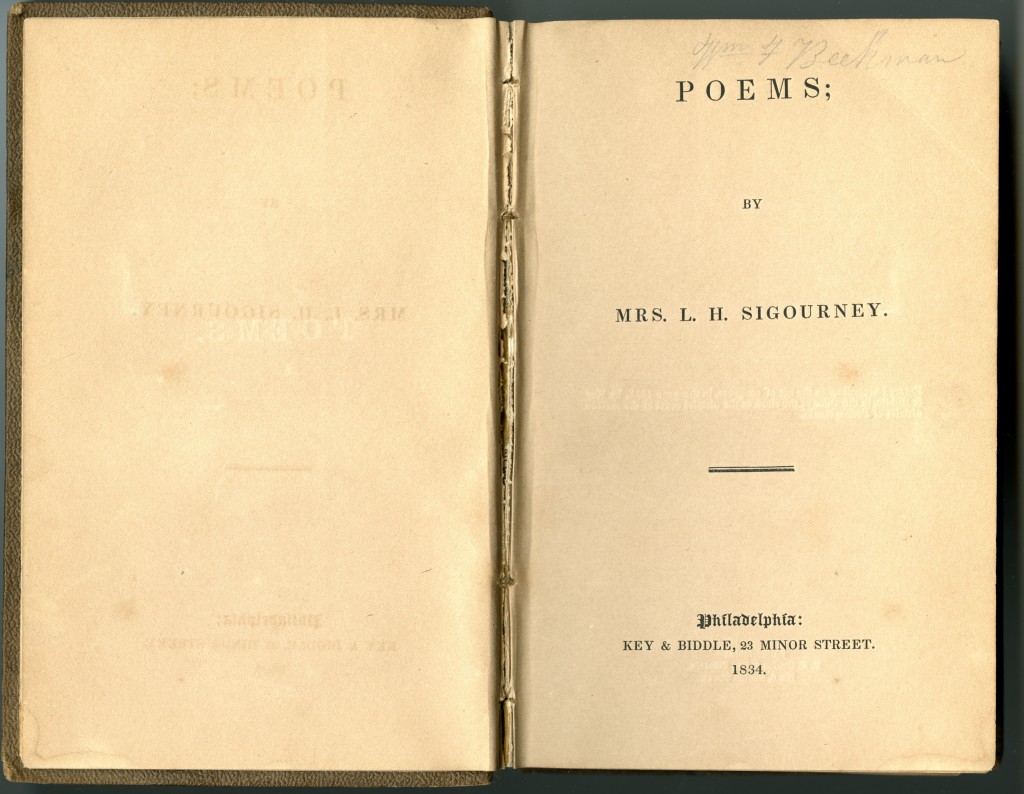

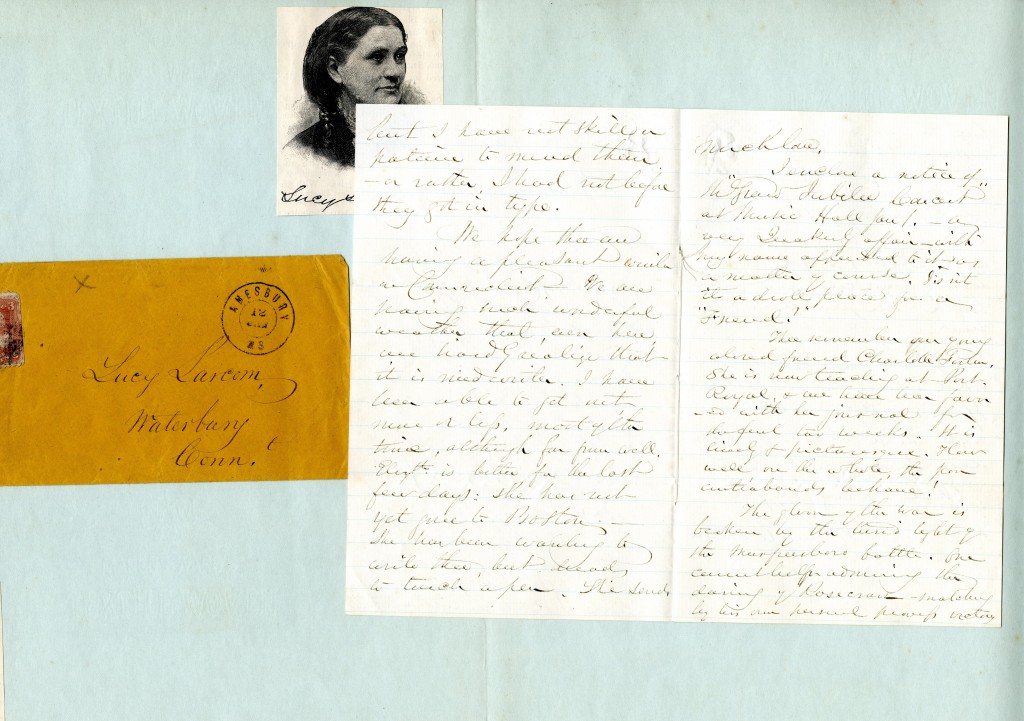

Lydia Huntley Sigourney. Poems by Mrs. L.H. Sigourney. Philadelphia: Key & Biddle, 1834.

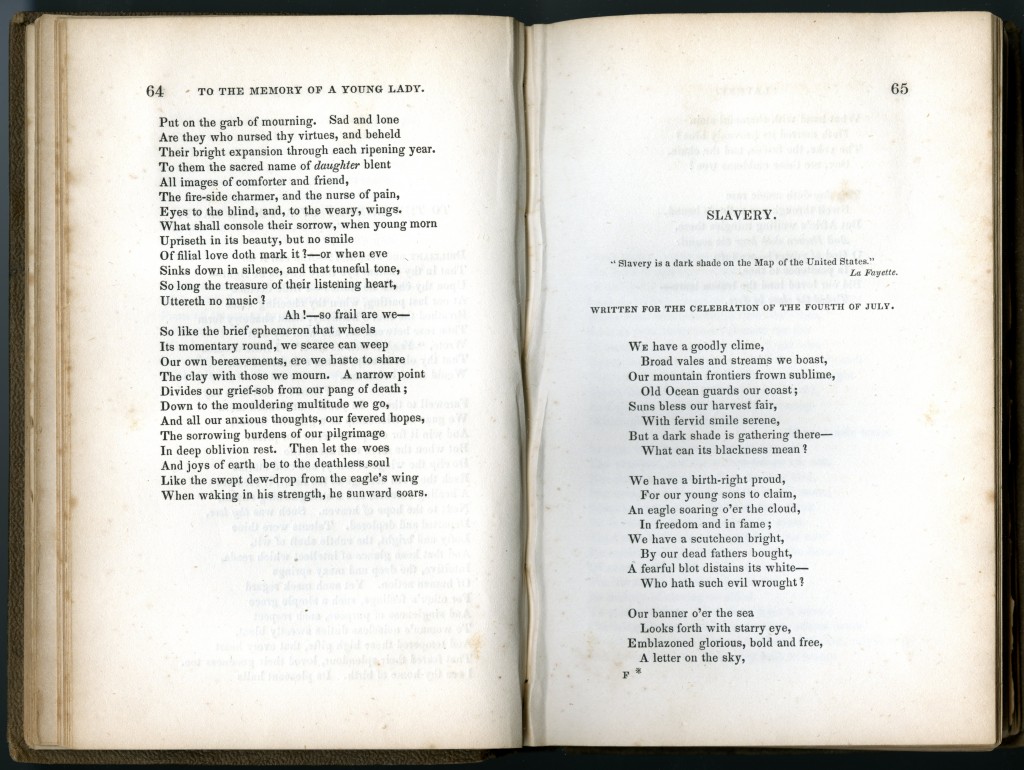

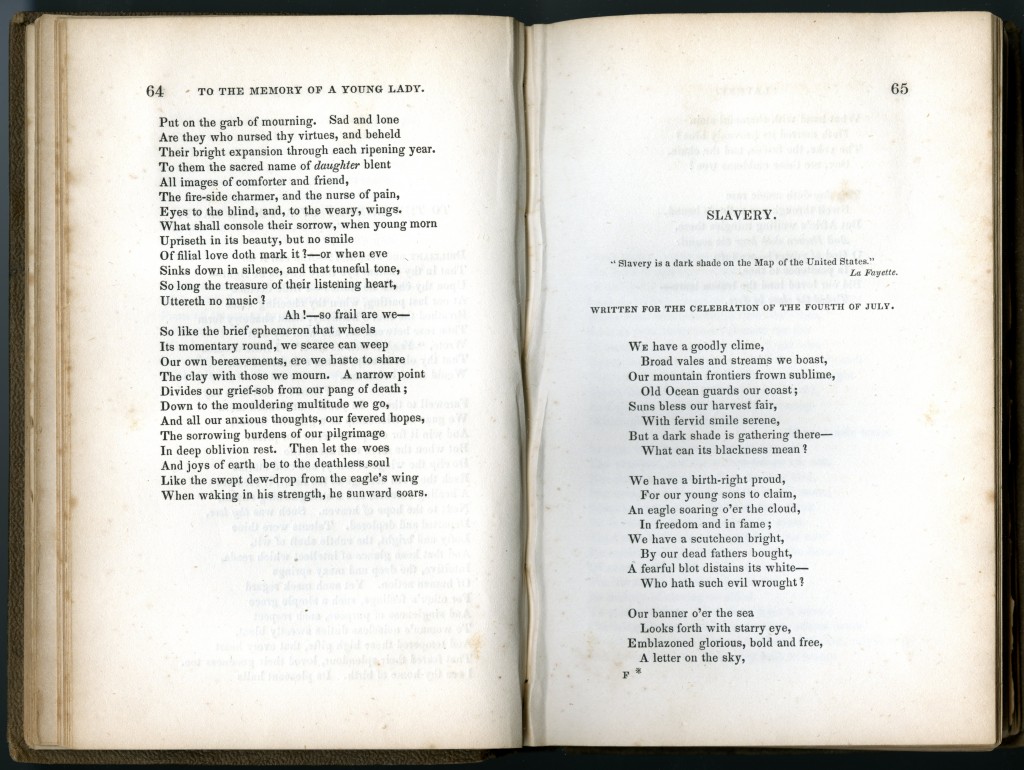

Lydia Huntley Sigourney (1791-1865) was a popular American poet in the early and mid-nineteenth century, who supported rights for women and the abolition of slavery, among many other reform causes. Her poem “Slavery: Written for the Celebration of the Fourth of July,” first published in this collected edition of Poems, was set to music in 1844 by lyricist and composer George W. Clark in his anti-slavery songbook The Liberty Minstrel. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS2830 .A2 1834]

The poem concludes on page 66:

The poem concludes on page 66:

What hand with shameful stain

Hath marred its heavenly blue?

The yoke, the fasces, and the chain,

Say, are these emblems true?

This day doth music rare

Swell through our nation’s bound,

But Afric’s wailing mingles there,

And Heaven doth hear the sound:

O God of power!—we turn

In penitence to thee,

Bid our loved land the lesson learn—

To bid the slave be free.

***

Eliza Lee Cabot Follen

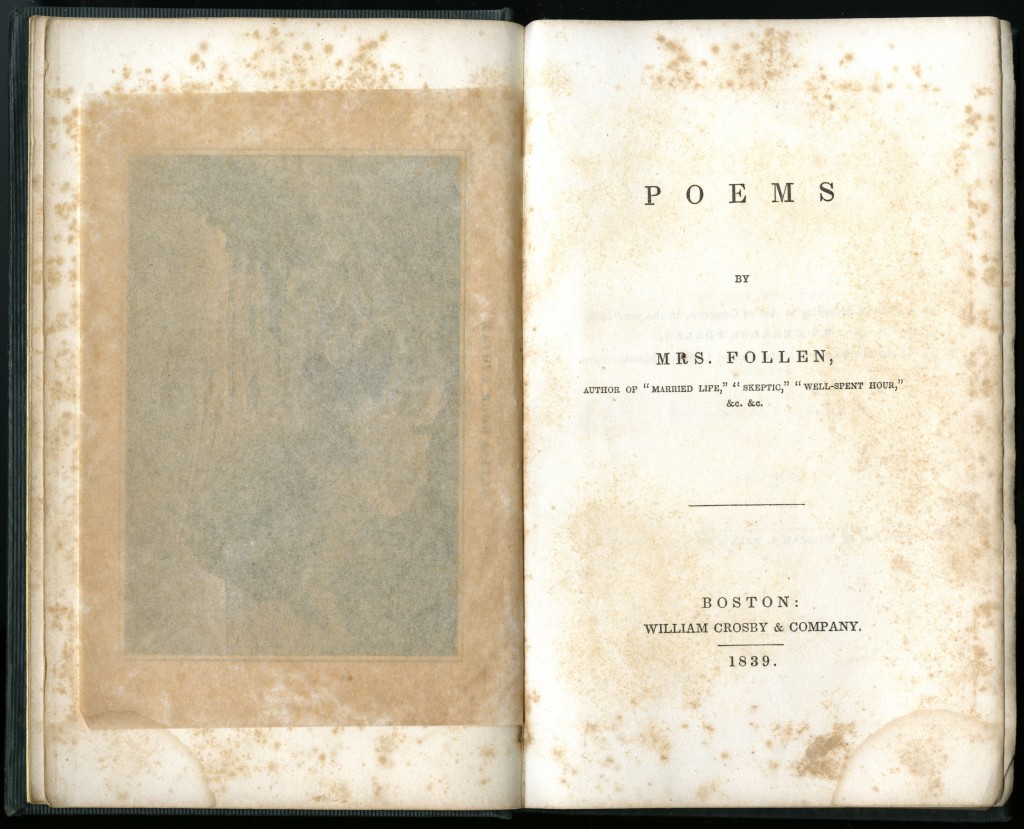

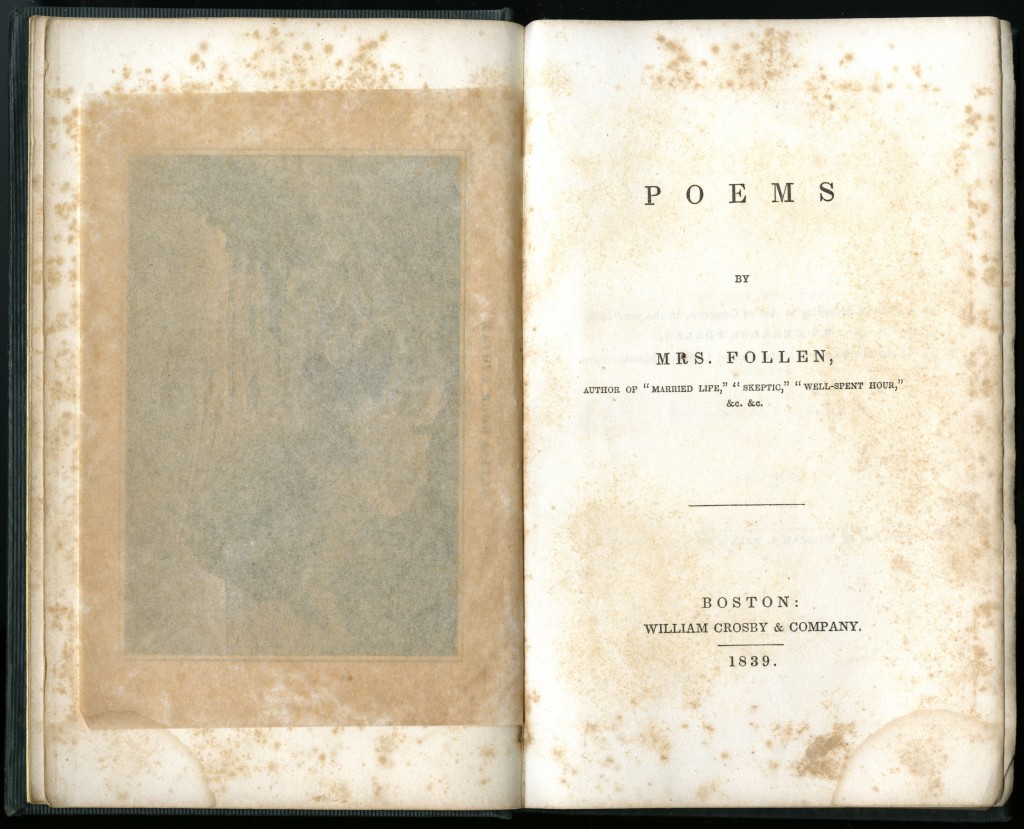

Eliza Lee Cabot Follen. Poems by Mrs. Follen. Boston: William Crosby & Company, 1839.

Eliza Lee Cabot Follen (1787-1860) was an editor, biographer, novelist, poet, playwright, children’s author, and lifelong abolitionist. Her Poems, published in 1839, includes political and religious verse, translations from German, and poems about slavery, including “Children in Slavery” shown here. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS1683 .F4]

***

***

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

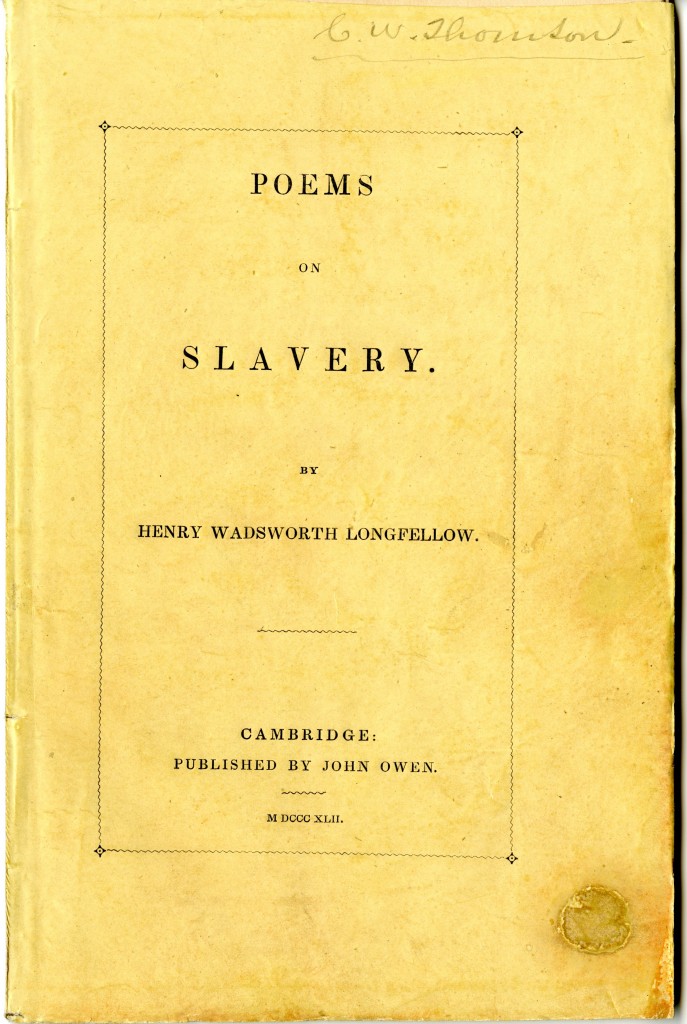

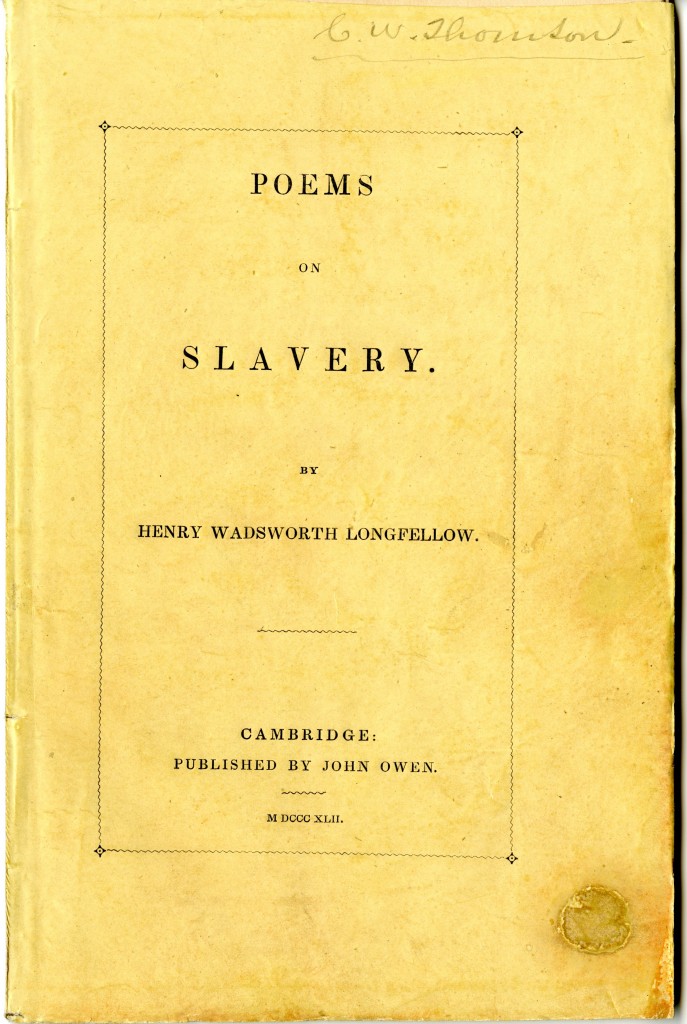

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Poems on Slavery. Cambridge: Published by John Owen, 1842.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Poems on Slavery. Cambridge: Published by John Owen, 1842.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), author of “Paul Revere’s Ride,” The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline, was one of the most popular American poets of the nineteenth century. He expressed his public support of abolitionism in this volume of poems, published in 1842. Considered the most overtly political of his writings, Longfellow composed seven of the eight poems in this small volume on his return voyage to the United States after visiting with and being inspired by radical poet Ferdinand Freiligrath (1810-1876) in Germany and Charles Dickens (1812-1870) in England. [ABLibrary 19thCent PS2265 .A1 1842]

Longfellow’s “The Warning” from Poems on Slavery (1842).

Longfellow’s “The Warning” from Poems on Slavery (1842).

Beware! The Israelite of old, who tore

The lion in his path,–when, poor and blind,

He saw the blessed light of heaven no more,

Shorn of his noble strength and forced to grind

In prison, and at last led forth to be

A pander to Philistine revelry,–

Upon the pillars of the temple laid

His desperate hands, and in its overthrow

Destroyed himself, and with him those who made

A cruel mockery of his sightless woe;

The poor, blind Slave, the scoff and jest of all,

Expired, and thousands perished in the fall!

There is a poor, blind Samson in this land,

Shorn of his strength and bound in bonds of steel,

Who may, in some grim revel, raise his hand,

And shake the pillars of this Commonweal,

Till the vast Temple of our liberties

A shapeless mass of wreck and rubbish lies.

***

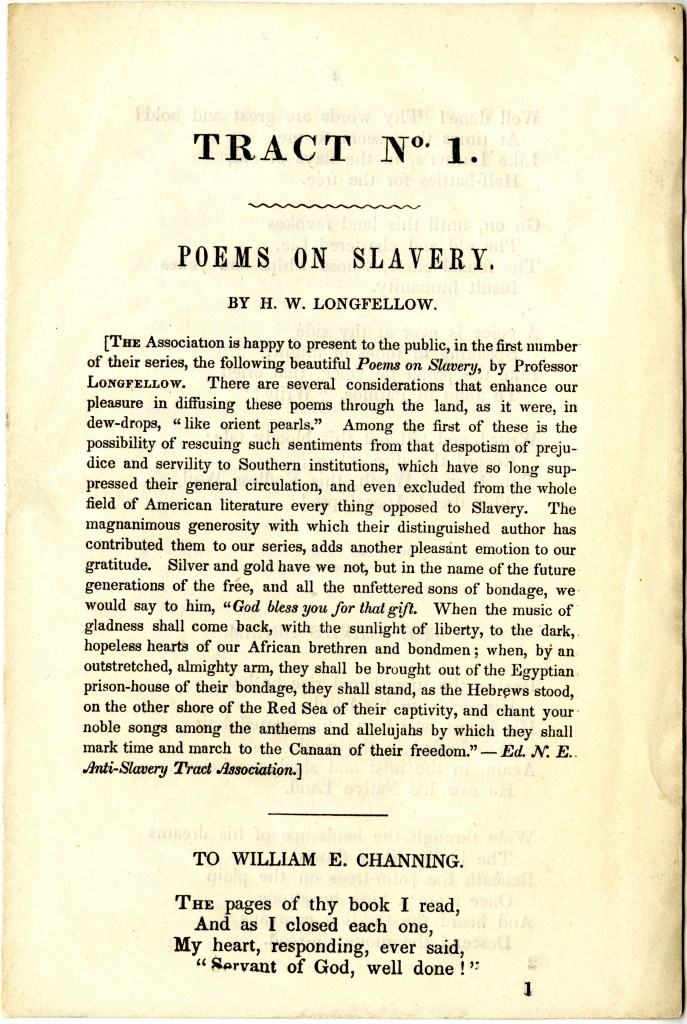

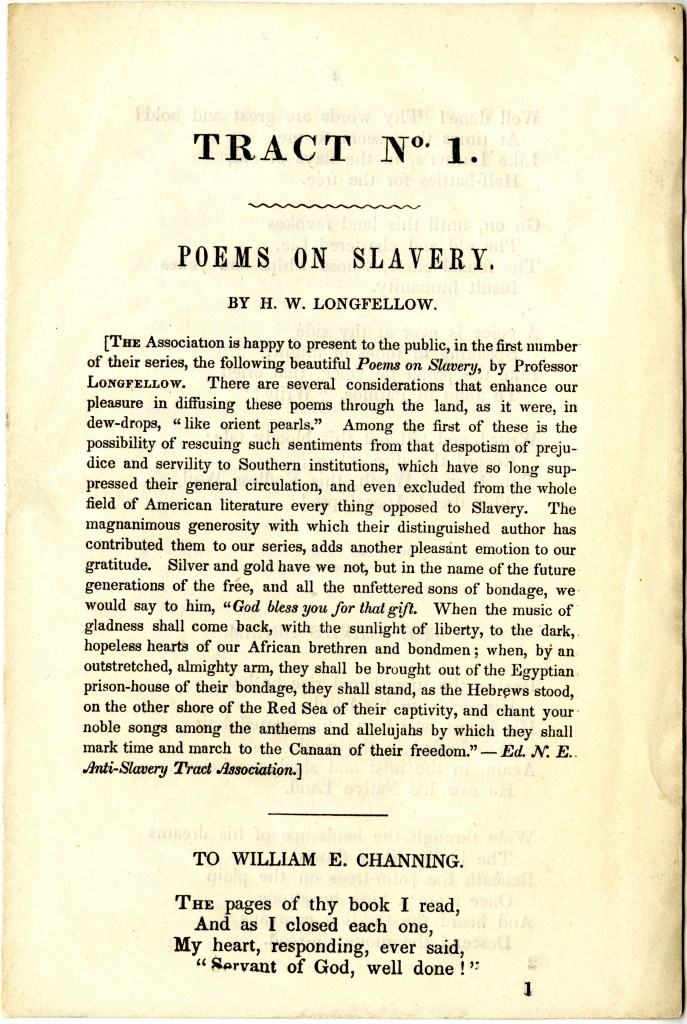

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Poems on Slavery. [Boston]: Published by the New England Anti-Slavery Tract Association, J.W. Alden, Publishing Agent, Boston, [1843].

Seven of Longfellow’s anti-slavery poems from his volume Poems on Slavery (1842) were reprinted by the New England Anti-Slavery Tract Society and distributed for free. [ABLibrary 19thCent OVZ PS2265 .A1 1843]

***

***

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Flower-de-Luce. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Flower-de-Luce. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

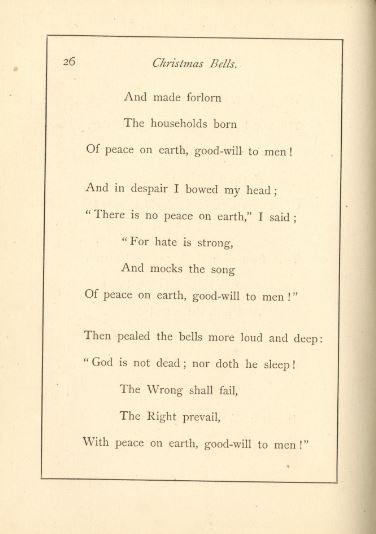

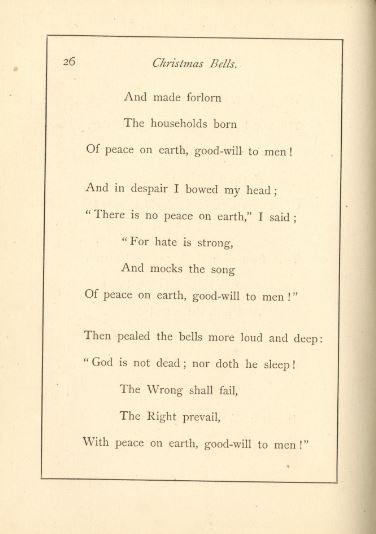

Although he did not return to the theme of slavery in his poetry after 1842, Longfellow did express hope for a reconciliation between the northern and southern states in the poem “Christmas Bells,” which he wrote on Christmas day in 1863 after his son Charles Appleton Longfellow, a soldier in the Union army, was severely injured in the Battle of New Hope Church in Virginia. The poem later served as the basis for the carol “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day.” [ABLibrary 19thCent PS2271 .F5 1867 c.2]

The conclusion of Longfellow’s poem “Christmas Bells” from Flower-de-Luce (1867).

The conclusion of Longfellow’s poem “Christmas Bells” from Flower-de-Luce (1867).

***

***

Charles Dickens

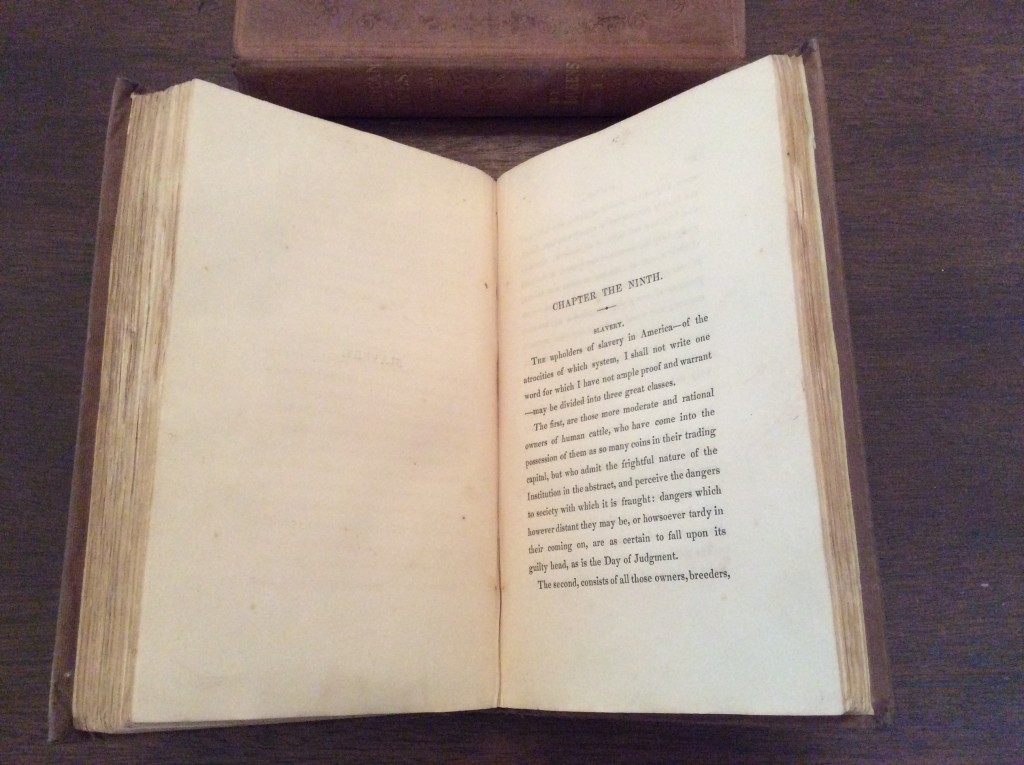

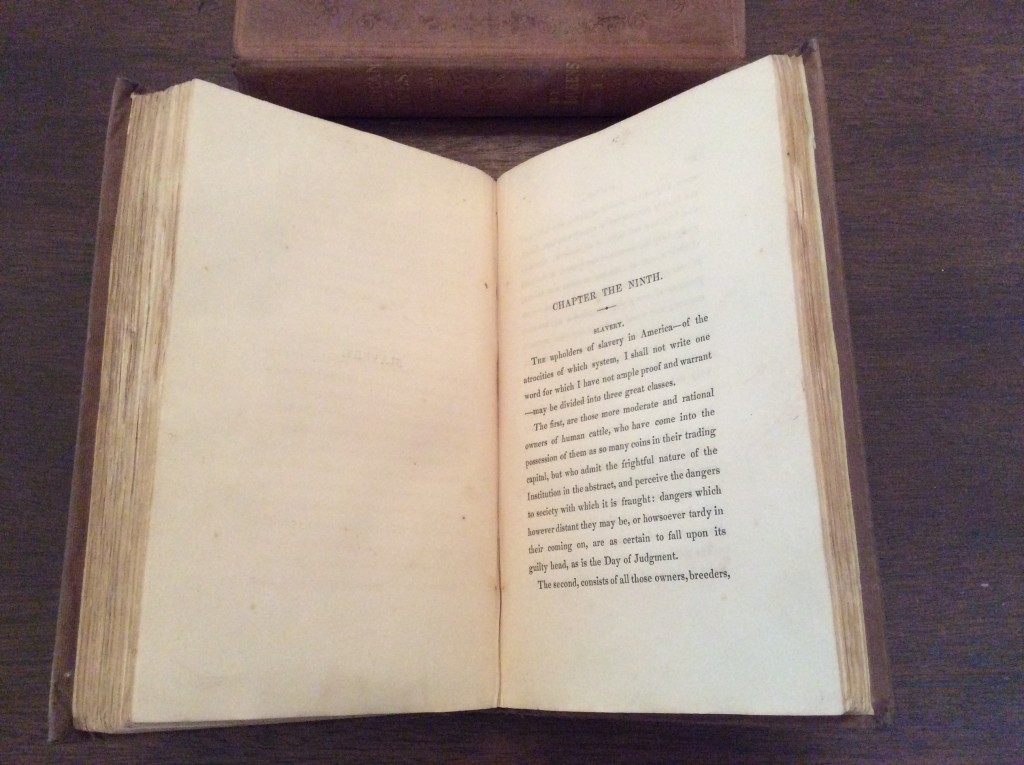

Charles Dickens. American Notes for General Circulation [2 vols.]. London: Chapman and Hall, 1842.

Charles Dickens. American Notes for General Circulation [2 vols.]. London: Chapman and Hall, 1842.

While visiting Charles Dickens in England in 1842, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow read Dickens’s recently-published American Notes for General Circulation, a travel book recounting Dickens’s visit to the United States earlier that year. Dickens offered a scathing critique of the institution of slavery in the penultimate chapter of this book, which English critic John Forster described as “one of the most powerful, effective antislavery tracts yet issued from the press.” [ABLibrary 19thCent E165 .D53 v.1-2]

***

***

Harriet Martineau

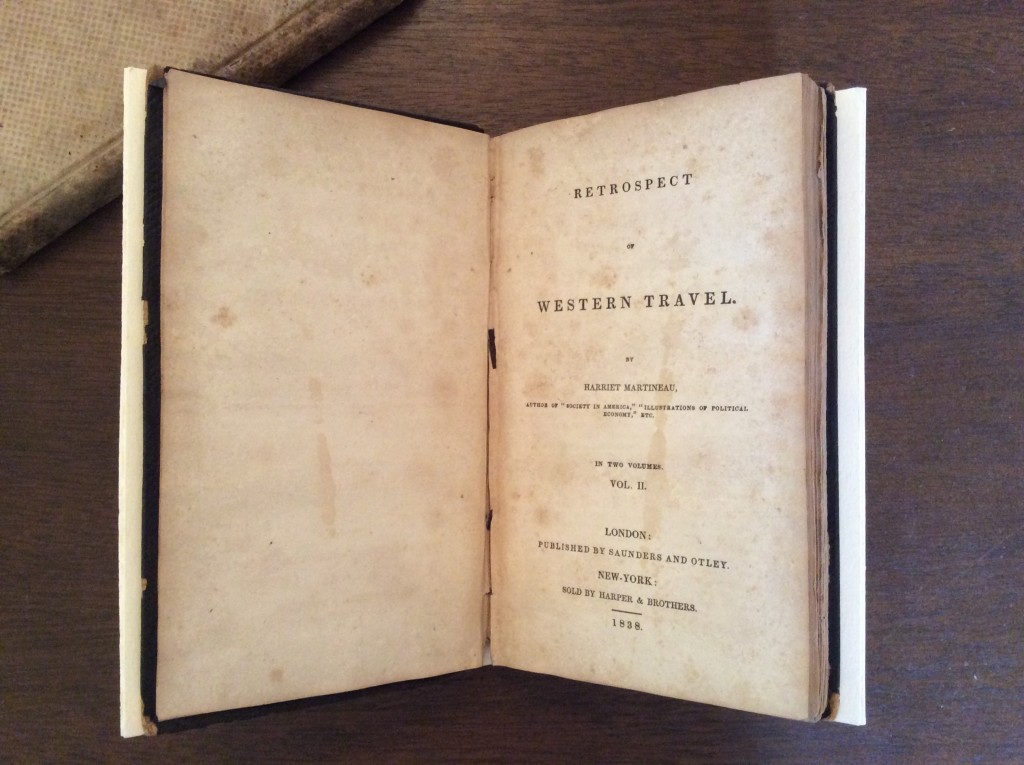

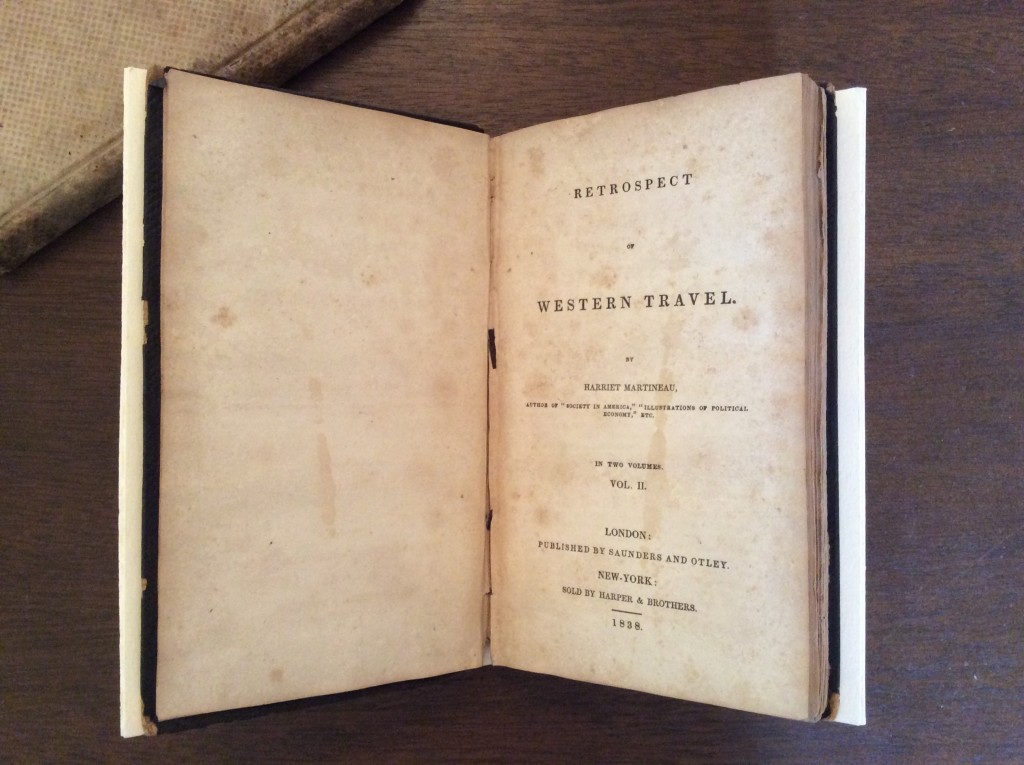

Harriet Martineau. Retrospect of Western Travel [2 vols.]. London: Published by Saunders and Otley; New York: Sold by Harper & Brothers, 1838.

Harriet Martineau. Retrospect of Western Travel [2 vols.]. London: Published by Saunders and Otley; New York: Sold by Harper & Brothers, 1838.

English writer and journalist Harriet Martineau (1802-1876) traveled extensively throughout the United States from 1834 to 1836 and recorded her observations in two books, Society in America (1837) and Retrospect of Western Travel (1838). In both books, Martineau expressed her opposition to slavery which she witnessed firsthand during her travels, finding the practice inconsistent with the idea of American democracy. [ABLibrary 19thCent E165 .M38 v.1-2]

***

***

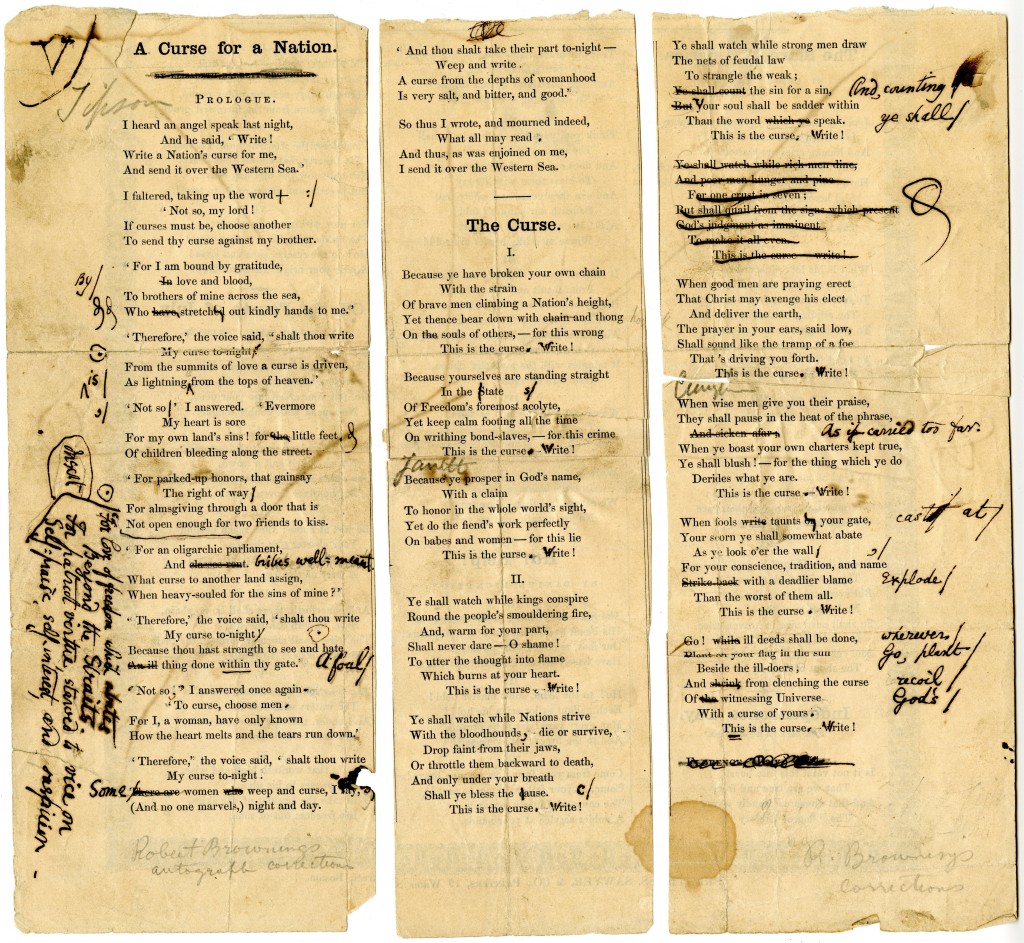

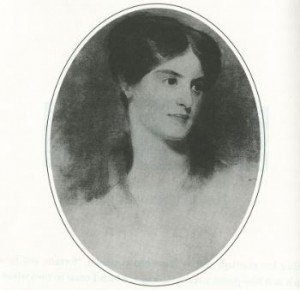

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

The Liberty Bell by Friends of Freedom. Boston: National Anti-Slavery Bazaar, 1848.

The Liberty Bell by Friends of Freedom. Boston: National Anti-Slavery Bazaar, 1848.

English poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861) wrote “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” for the Boston anti-slavery annual The Liberty Bell, published from 1839 to 1858. Barrett Browning was invited to contribute the poem for publication by Maria Weston Chapman (1806-1885), longtime editor of the annual, and poet James Russell Lowell (1819-1891), a correspondent of Barrett Browning’s since 1842. [ABLibrary Rare X 326 C466l 1848]

In a letter written to her American friend Cornelius Mathews in early 1847, Barrett Browning makes these comments about sending the manuscript of the poem to America:

My conscience has been restless about it ever since, (whenever I thought that way,) but neither head nor heart were at liberty sufficiently to do anything. What I have sent at last, my belief is, will never be printed in America, or will, if it should be, bring the writer into a scrape of disfavor. But I did only write conscientiously, you know, in writing at all; and my “Cry of the Children,” was not less written against my own country.

***

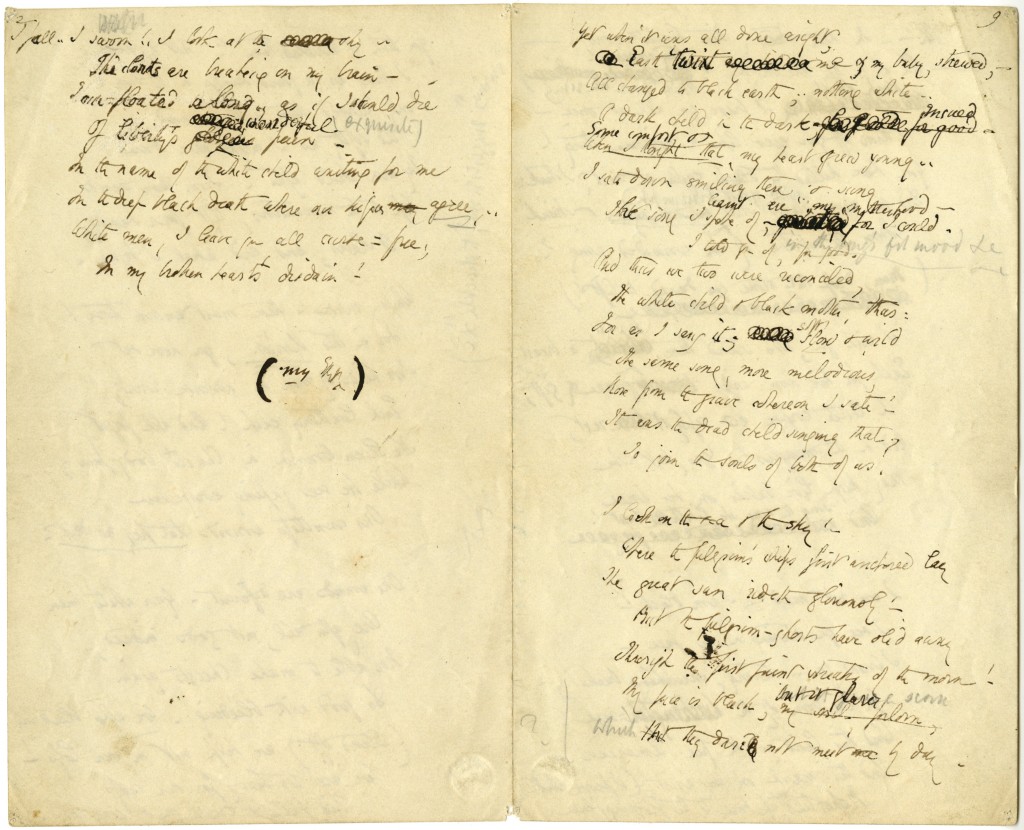

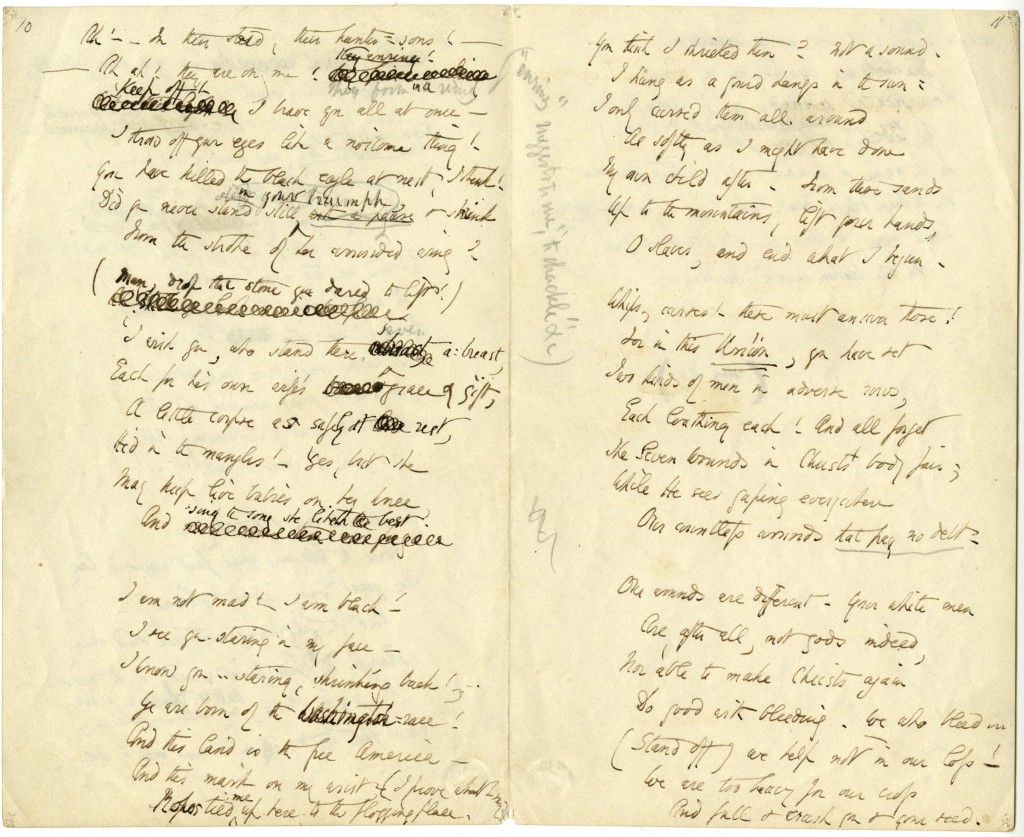

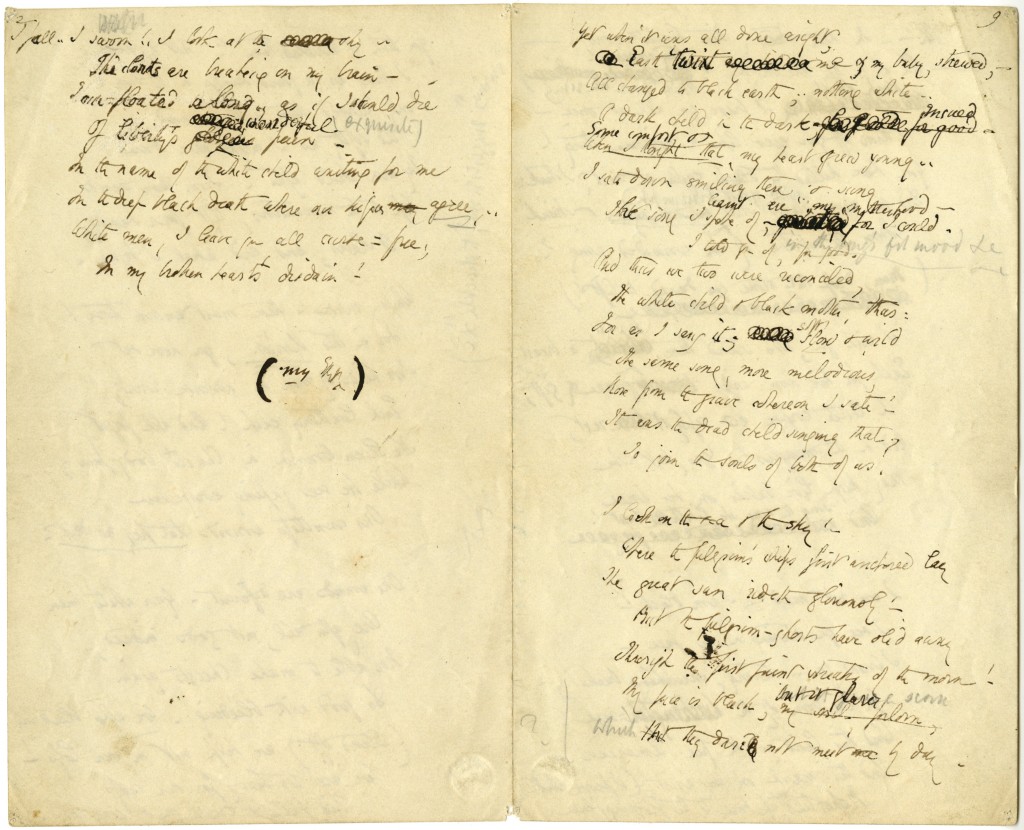

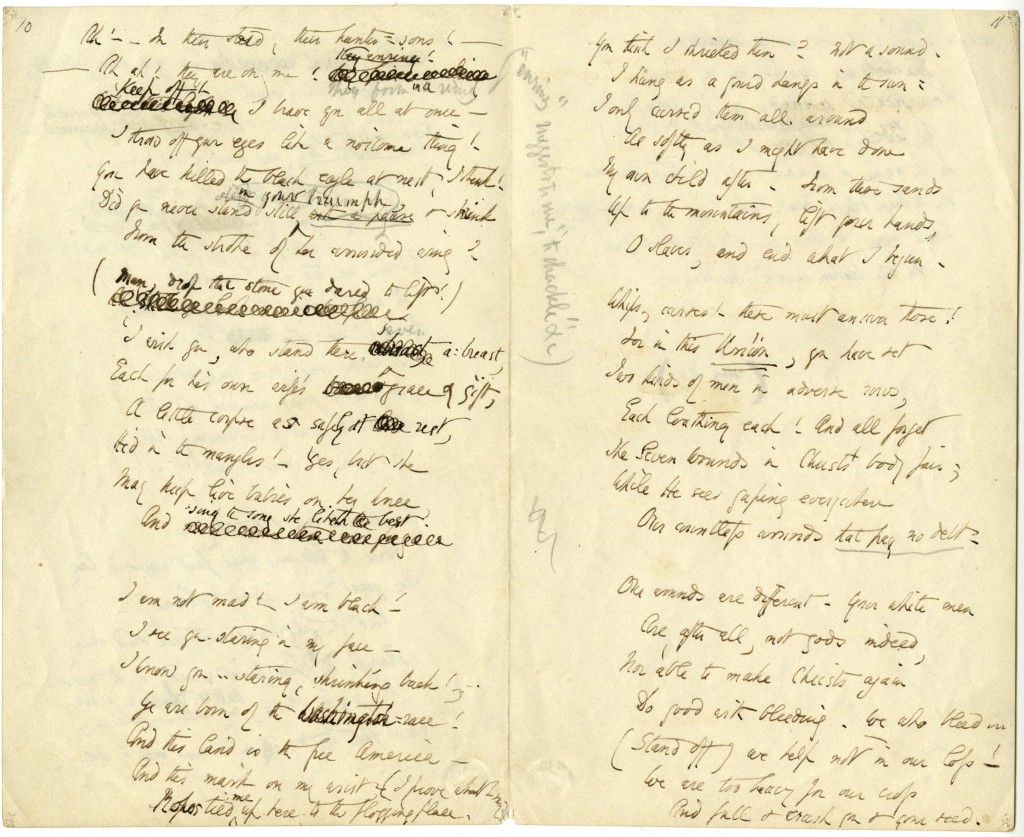

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point.” Autograph Manuscript. Undated.

This is the first part of a draft of “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point,” which includes stanzas 1-13, without stanza 7. In this draft, the poem is titled “Black and Mad at Pilgrim’s Point.” Robert Browning has annotated the draft in pencil.

***

***

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point.” Autograph Manuscript. Signed “EBB.” Undated.

This final part of the above draft includes stanzas 27-36. On the final page of the manuscript, Robert Browning has enclosed Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s initials and his written word “my” in strong brackets. The middle part of the draft, including stanzas 14-26, is at the British Library. All three parts are annotated by Robert Browning.

***

***

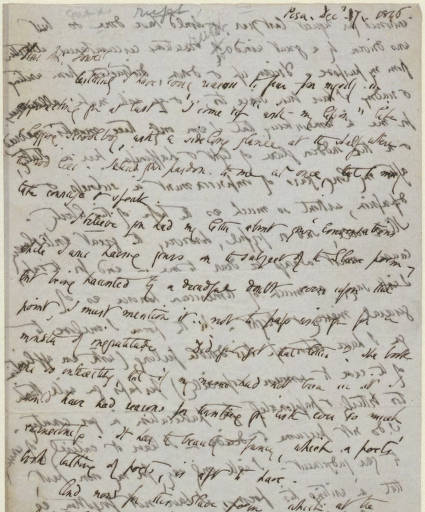

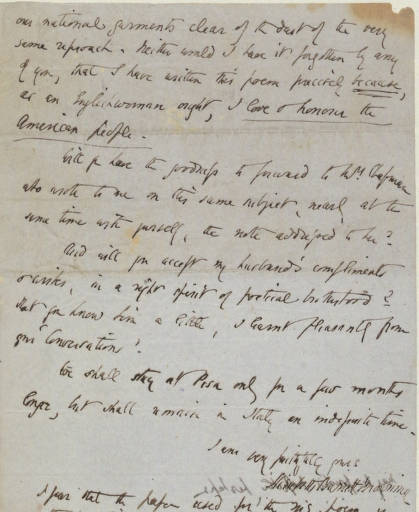

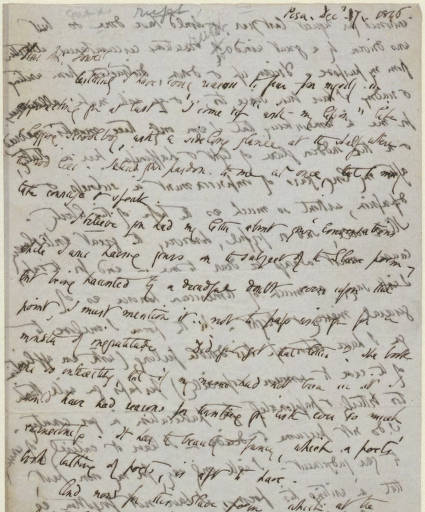

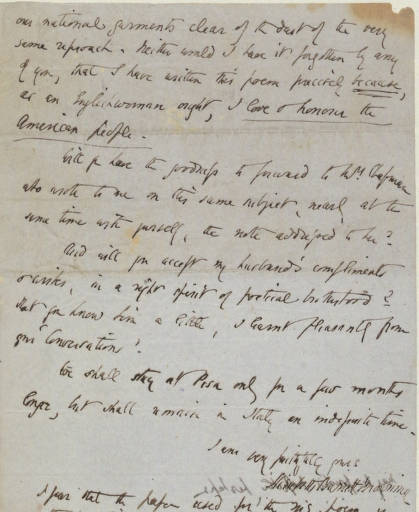

Letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to James Russell Lowell. 17 December 1846.

Enclosed with this letter to James Russell Lowell was Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s manuscript of the “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point.”

In the letter, she refers to her recent marriage and to her concern regarding the reception of the poem:

And now for this Slave-poem, which at the eleventh hour, I enclose to you. I ought to have at once answered your request last year, & should have done so but was driven by a great wind of vexatious circumstances, altogether from my purpose. Driven up & down, distracted from writing & reading I have been since, too, .. & you will make allowances for me in remembering that I am only three month’s married, & in the sudden glare of light & happiness, here in Italy, after my long years of imprisonment in sickness & depression, without so much as the hope of this liberty. Ill or well, sad or joyful, however, the great antislavery cause must always be dear to me,—and for the sake, I will say, as much of American honour as of general mercy & right– In the poem I enclose to you I have taken up this double feeling, (with an application of the case to women especially) perhaps you will think too bitterly & passionately for publication in your country. I do not presume to decide—I leave it entirely, of course, to your judgement– I will only say, for my own part, that in writing this poem, I have not forgotten, as an Englishwoman, that we have scarcely done washing our national garments clear of the dust of the very same reproach. Neither would I have it forgotten by any of you, that I have written this poem precisely because, as an Englishwoman ought, I love & honour the American people.

***

***

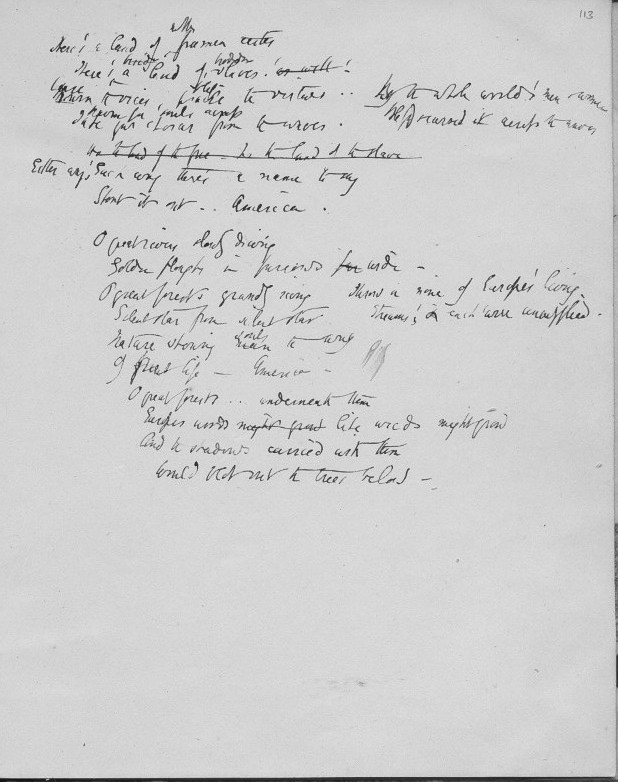

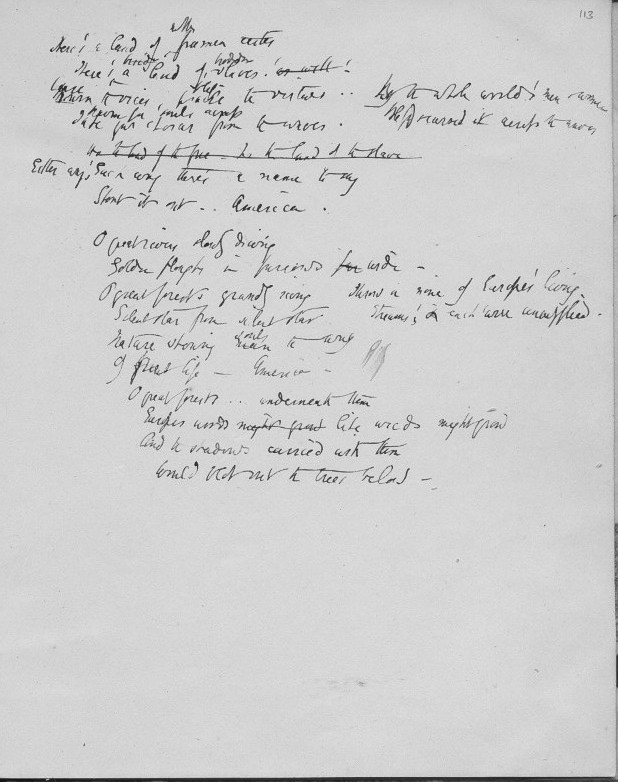

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. “An Ode to America.” Manuscript Draft. [1846].

This draft, contained in a notebook belonging to Elizabeth Barrett Browning and acquired by the Armstrong Browning Library in 2008, was likely written by the poet around the time she was writing “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point.” The poem was not published during Barrett Browning’s lifetime, but a transcription of this draft was included in The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, edited by Sandra Donaldson, in 2010.

Transcription of the manuscript draft of “An Ode to America” in The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning [5 vols.] (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010). [ABLibrary Non-Rare 821.82J D676w 2010 v.5]

Transcription of the manuscript draft of “An Ode to America” in The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning [5 vols.] (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010). [ABLibrary Non-Rare 821.82J D676w 2010 v.5]

***

***

The Liberty Bell by Friends of Freedom. Boston: National Anti-Slavery Bazaar, 1856.

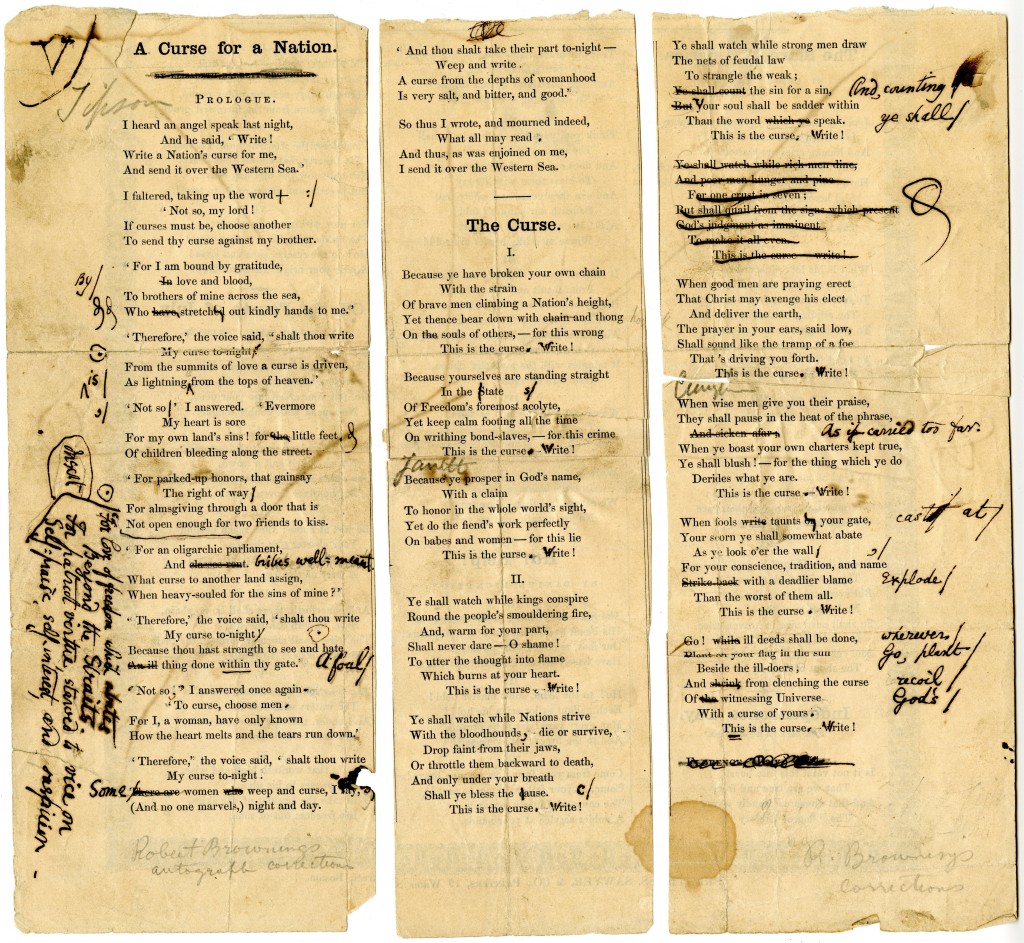

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem “A Curse for a Nation,” denouncing slavery in America, first appeared as the opening poem in the 1856 issue of the Boston anti-slavery annual The Liberty Bell. Barrett Browning wrote the poem in response to a request from her Boston anti-slavery contacts just as she had responded some years earlier with “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point.” [ABLibrary Rare X326 C466l 1856]

***

***

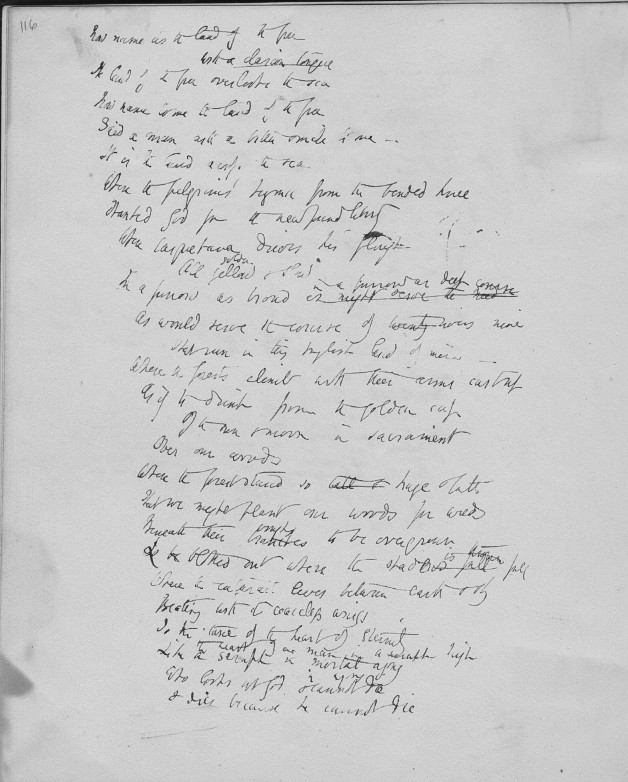

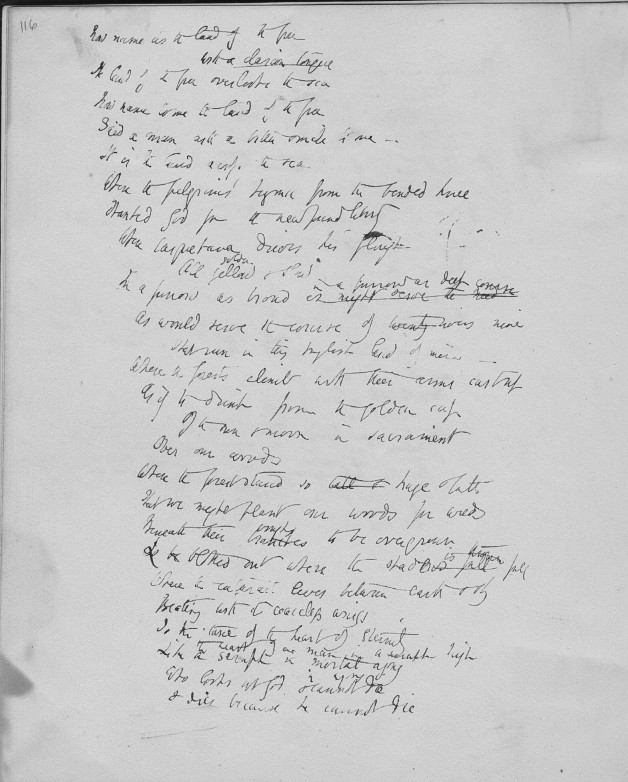

Printer’s copy of “A Curse for a Nation.” [1856].

This printer’s copy of “A Curse for a Nation” shows Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s corrections and additions for publication in The Liberty Bell of 1856.

***

***

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Napoleon III in Italy and Other Poems. New York: C. S. Francis & Co., 1860.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Napoleon III in Italy and Other Poems. New York: C. S. Francis & Co., 1860.

“A Curse for a Nation” proved to be one of Barrett Browning’s most controversial works when it was reprinted as the last poem in her Poems Before Congress (1860). The majority of the poems in this volume criticized England for its nonintervention in Italy’s struggle for liberation, leading English reviewers to believe that the curse was directed at England not America. Barrett Browning maintained that the poem was about America, but wrote to a friend:

In fact, I cursed neither England nor America … the poem only pointed out how the curse was involved in the action of slave-holding.

This copy of the first American edition of Poems Before Congress, published under the title Napoleon III in Italy and Other Poems, bears an inscription by J.S. Guitean, dated 3 July 1860, to E.N. Biddle, a Union general in the American Civil War. [ABLibrary Rare X 821.82 L F818n c.4]

***

Frances Anne Kemble

Frances Anne Kemble. Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863.

Frances Anne Kemble. Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863.

Frances “Fanny” Anne Kemble (1809-1893) was a famous British actress and writer. In 1834, she married Pierce Butler, an American who, two years later, inherited his grandfather’s cotton and rice plantations on the Sea Islands of Georgia. In an effort to convince Fanny, an abolitionist, of the benefits of slavery, Butler took her to the plantations in the winter of 1838-1839. While there Fanny wrote letters to friends and kept a diary. These writings documented her observations of slavery and circulated, against her husband’s wishes, among New England abolitionists. Eventually published in 1863 during the Civil War as Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation, the book was a best-seller. Fanny separated from her husband in 1845, and the marriage ended in divorce in 1849. [ABLibrary Rare X 975.803 K31j 1863]

***

Bibliography:

Basker, James G., ed. American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation. New York: Library of America, c2012. Print.

Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, c2004. Print.

Clinton, Catherine. Fanny Kemble’s Civil Wars. New York: Simon & Schuster, c2000. Print.

Currier, Thomas Franklin. A Bibliography of John Greenleaf Whittier. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard UP, 1937. Print.

De Rosa, Deborah C. Into the Mouths of Babes: An Anthology of Children’s Abolitionist Literature. Westport, Connecticut; London: Praeger, 2005. Print.

Donaldson, Sandra, general ed. The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. 5 vols. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010. Print.

Gerson, Noel B. Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Biography. New York: Praeger, 1976. Print.

Gray, Janet, ed. She Wields a Pen: American Women Poets of the 19th Century. London: J.M. Dent, 1997. Print.

Hansen, Andrew C. “Rhetorical Indiscretions: Charles Dickens as Abolitionist.” Western Journal of Communication 65.1 (2001): 26-44. Web. 11 March 2015

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, c2015. Web. 11 March 2015 <https://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/>

Hedrick, Joan D. Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life. New York; Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994. Print.

Martineau, Harriet. Writings on Slavery and the American Civil War. Ed. Deborah Anna Logan. DeKalb: Northern Illinois UP, c2002. Print.

Stone, Marjorie, and Beverly Taylor, eds. Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Selected Poems. Buffalo, New York: Broadview Editions, 2009. Print.

Trent, Hank, ed. Narrative of James Williams, an American Slave. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2013.

Woodwell, Roland H. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Biography. Haverhill, Massachusetts: Published under the auspices of The Trustees of the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead, 1985. Print.