The slightest emotion of disinterested kindness that passes through the mind improves and refreshes that mind, producing generous thought and noble feeling, as the sun and rain foster your favourite flowers. Cherish kind wishes, my children; for a time may come when you may be enabled to put them in practice.

Mary Russell Mitford

Our Village: Sketches of Rural Character and Scenery

London: Ward, Lock and Company, 1870

“The Residuary Legatee,” vol. 5, p. 145

Mary Russell Mitford was the only daughter of a father with excessive spending habits. At age ten Mitford won a substantial sum of money in a lottery, which her father quickly spent. Mitford had to work hard to earn enough to support both herself and her father. Luckily, Mitford’s writing was well liked and she and her father were able to survive primarily on the proceeds of her literature. As a poet, novelist, dramatist, and playwright, Mitford was a diverse writer but her prose was the most popular.

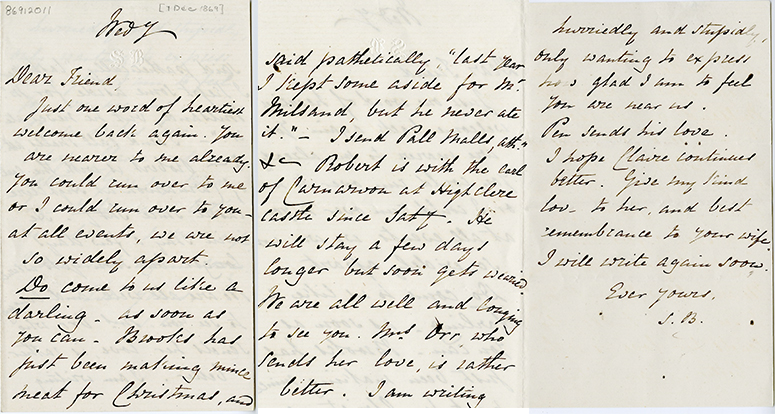

Mitford was a close friend and frequent correspondent of Elizabeth Barrett’s, particularly before Barrett’s marriage to Robert Browning. Their letters to each other are full of literary commentary as well as discussions of their daily lives. As a token of their friendship, Miss Mitford gave Elizabeth Barrett an important gift—Flush, EBB’s beloved spaniel. The Armstrong Browning Library has 24 volumes written by Miss Mitford and nine letters.

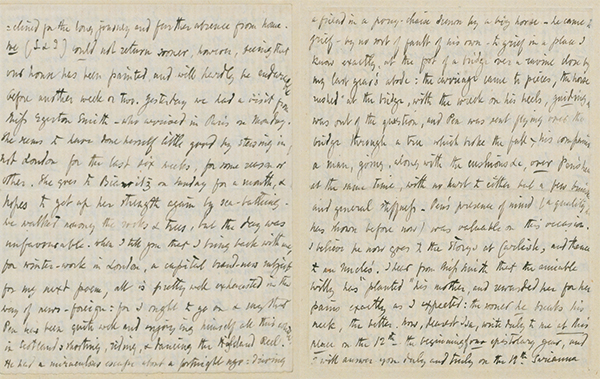

One of Miss Mitford’s acquaintances was John Kenyon, who was a distant cousin of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. This letter from Miss Mitford to Mr. Kenyon talks about geranium seeds given to her by Miss Catharine Sedgwick, then progresses to a review of Miss Sedgwick’s book, presents an offer to share geranium cuttings with Mr. Kenyon, and ends with a discussion of American authors. The letter provides a glimpse into this popular and appealing author, known for her unaffected spontaneous humor, quick wit, and literary skill.

Melinda Creech