There were two more literary allusions in this week’s episode of Downton Abbey, both of which connect to the Brownings.

When Lord Grantham and Mr. Drewe, the son of the recently deceased tenant farmer, are discussing whether or not he will be allowed to remain as a tenant, Lord Grantham says he is no “Simon Legree.” This, of course, is a reference to the cruel slave dealer in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the best-selling novel of the 19th century and the second best-selling book of that century, following the Bible.

The author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, was one of the many American correspondents of the Brownings. (Soon the Armstrong Browning Library will shortly be featuring an exhibit, “…from America: The Brownings’ American Correspondents.) There are six recorded letters between the Brownings and Harriet Beecher Stowe between 1857 and 1861, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning makes references to Stowe in six more letters. One of these letters is in the collection at the Armstrong Browning Library.

The author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, was one of the many American correspondents of the Brownings. (Soon the Armstrong Browning Library will shortly be featuring an exhibit, “…from America: The Brownings’ American Correspondents.) There are six recorded letters between the Brownings and Harriet Beecher Stowe between 1857 and 1861, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning makes references to Stowe in six more letters. One of these letters is in the collection at the Armstrong Browning Library.

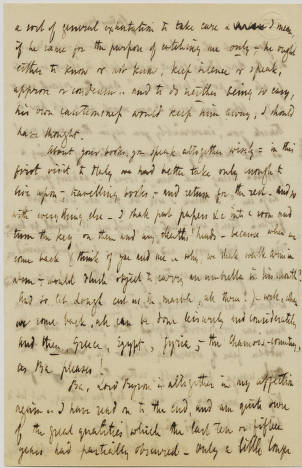

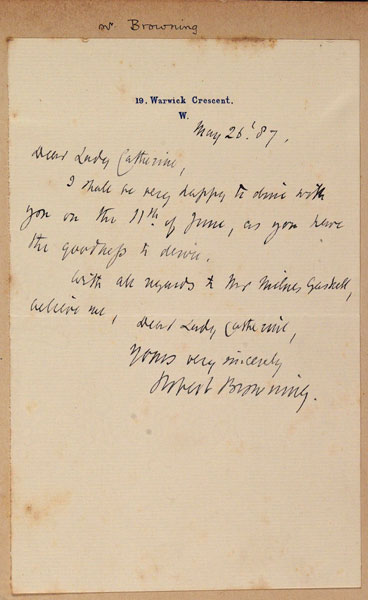

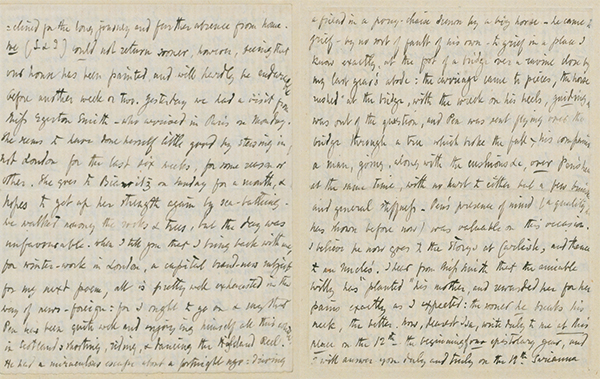

Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Harriet Beecher Stowe

[?24 March 1860]

Fifteen Harriet Beecher Stowe books are in the ABL’s collection, including a first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Among the books are two volumes of Stowe’s poetry, which are in the digital collection of 19th Century Women Poets.

The other literary allusion focused on Lord Byron. Lord Grantham is complimented on his rather pithy statement about the past and the future. His dowager mother responds, “It was too good. One thing we don’t want is a poet in the family.” When Isobel Crawley asks if that would be a bad thing, the dowager answers, “The only poet peer I am familiar with is Lord Byron. And I presume we all know how that ended.” The dowager was referring to Byron’s divorce, remarriage, accusations against him of sodomy and incest, his affairs, and his eventual flight from England to Italy. Obviously, his lifestyle was not the sort that the dowager would approve.

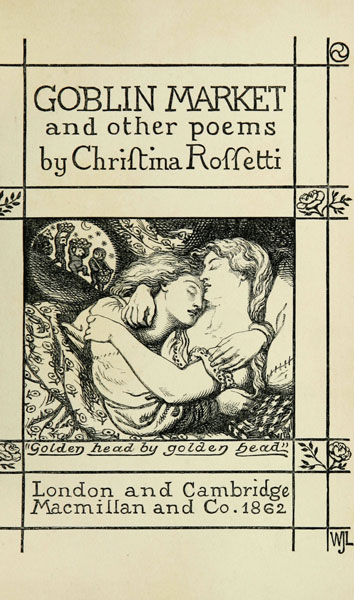

The Brownings, however, admirers of Byron’s poetry owned ten copies of Byron’s work, two portraits of the poet, and a copy of Byron’s verses in an unidentified hand.

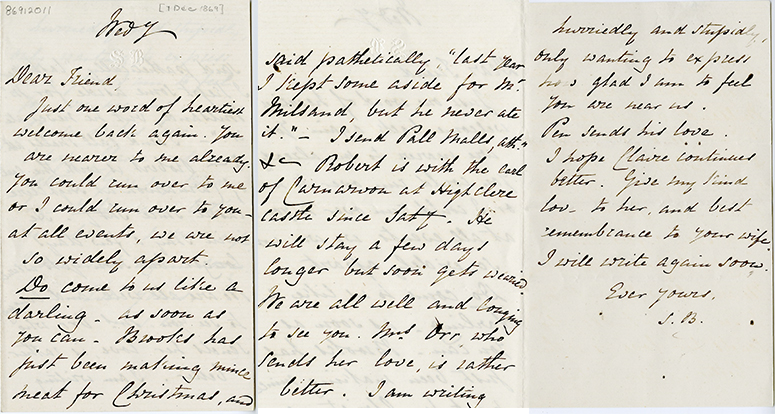

Robert makes this reference to Byron in a love letter he wrote to Elizabeth Barrett Browning on August 22, 1846:

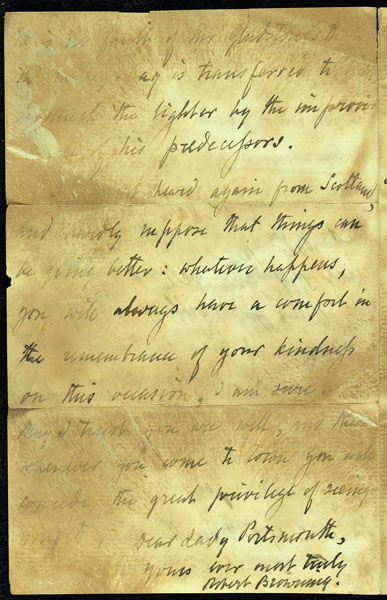

Ba, Lord Byron is altogether in my affection again .. I have read on to the end, and am quite sure of the great qualities which the last ten or fifteen years had partially obscured- Only a little longer life and all would have been gloriously right again. I read this book of Moore’s [Letters and Journals of Lord Byron: with Notices of His Life by Thomas Moore, 1830] too long ago: but I always retained my first feeling for Byron in many respects .. the interest in the places he had visited, in relics of him: I would at any time have gone to Finchley to see a curl of his hair or one of his gloves, I am sure–while Heaven knows that I could not get up enthusiasm enough to cross the room if at the other end of it all Wordsworth, Coleridge & Southey were condensed into the little china bottle yonder, after the Rosicrucian fashion .. they seem to “have their reward” and want nobody’s love or faith.

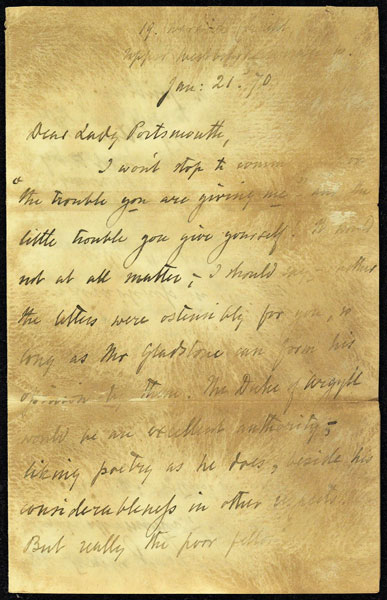

Robert Browning to Elizabeth Barrett Browning

22 August 1846

Robert Browning’s life offers some parallels to Lord Byron’s and some differences. Although his marriage to EBB was clandestine, he was a devoted and loving husband. He did leave England to live in Italy, but his leaving was not under duress, and he did return to England often and freely.

Notes and Queries:

Could other similarities and differences be found in the lives of these great poets?