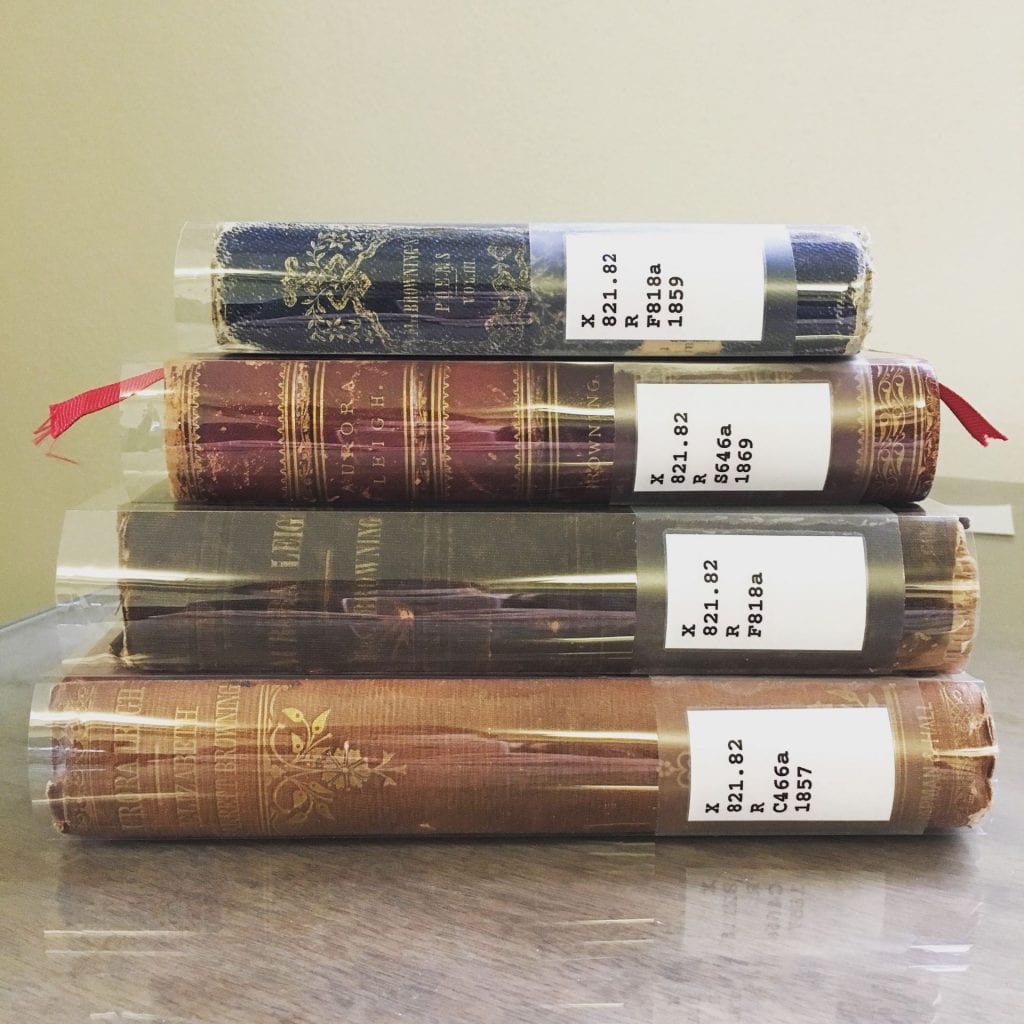

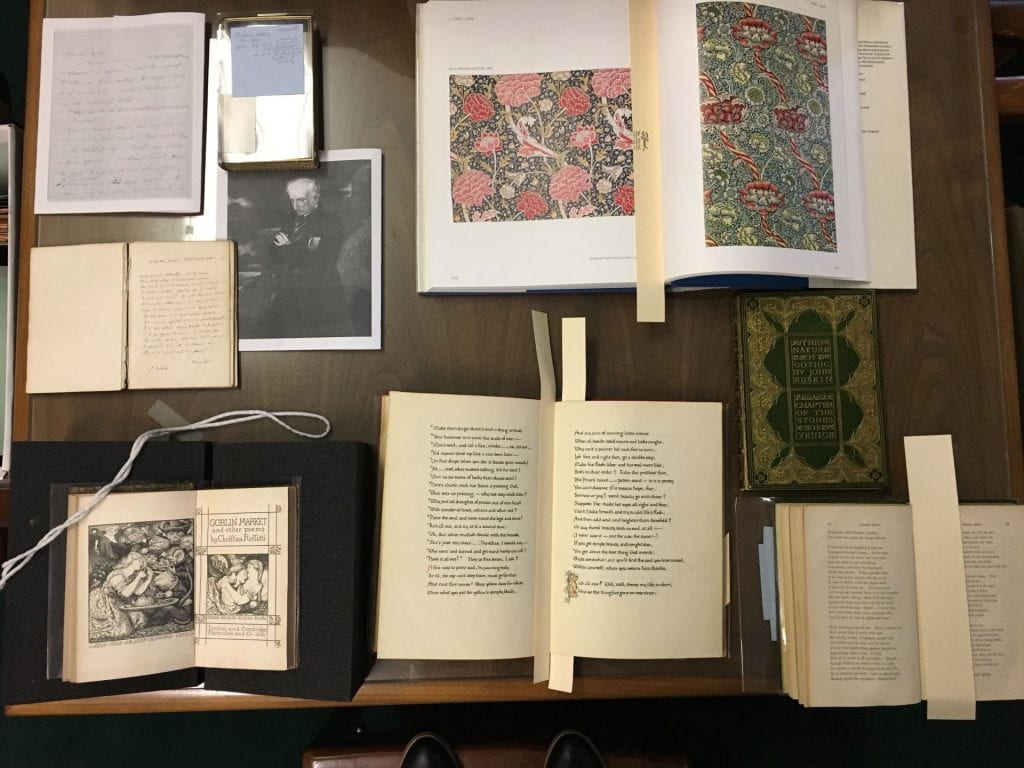

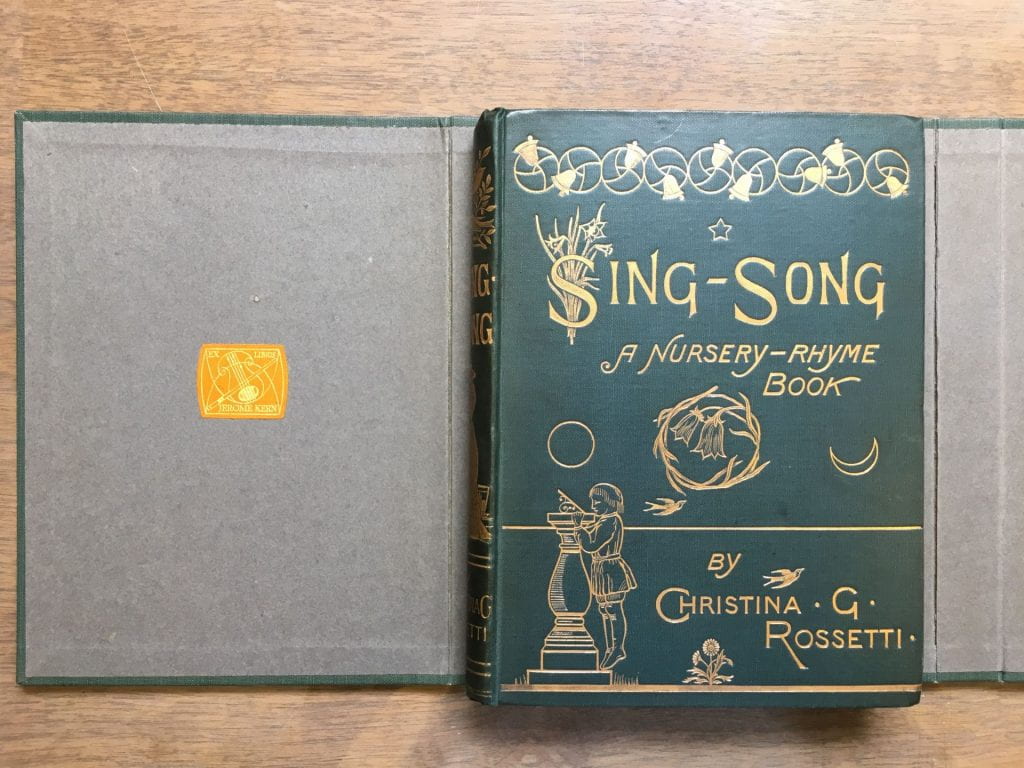

On December 9th at 9:05am, Dr. Kristin Pond’s English 3351: Literary Networks in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Centuries course will be presenting their Great Exhibition. This is a class project which requires students to explore what artifacts, including original letters, manuscripts and books, photographs, and actual objects exist at the Armstrong Browning Library related to each student’s assigned author.

The exhibition will be on display in the Hankamer Treasure Room for the entire morning December 9th, 2019.

To prepare for the exhibition, students wrote a short biography of their author and practiced analyzing an artifact for what it reveals about their author. A sample of one student’s preliminary research follows.

John Keats

The April 1818 edition of The Quarterly Review reads “Keats is unhappily a disciple of the new school [of] Cockney poetry; which may be defined to consist of the most incongruous ideas in the most uncouth language (1).”

Before John Keats reached worldwide fame, he could not escape being a subject of harsh criticisms such as the sentiment above. The Quarterly Review, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, and other prominent literary magazines all branded Keats into a pejorative group known as the Cockney school. This group included English writers such as Leigh Hunt, William Hazlitt, and Percy Shelly, and they were all collectively criticized for a number of shaky reasons. Keats in particular was attacked because of his lower-class upbringing; an editor of The Quarterly Review particularly disapproved highly of the working class meddling with intellectual forms such as poetry. The Review’s editor labels Keats an ‘uneducated and flimsy stripling’ and slams Endymion as an “imperturbable drivelling idiocy” before concluding that “It is a better and wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the shop Mr John. (2)” We cannot be sure exactly how Keats reacted to this virulence. It’s possible that he was completely undeterred, and it is possible that it adversely affected his health (Shelly actually thought that the criticism contributed to his early death (3)). Whatever the reaction of Keats, the latter opinion was loud enough to cause Blackwood Magazine to go on the defense after his death, writing:

Mr. Keats died in the ordinary course of nature. Nothing was ever said in this Magazine about him, that needed to have given him an hour’s sickness; and had he lived a few years longer, he would have profited by our advice, and been grateful for it, although perhaps conveyed to him in a pill rather too bitter. Hazlitt, Hunt, and other unprincipled infidels, were his ruin. Had he lived a few years longer, we should have driven him in disgust from the gang that were gradually affixing a taint to his name. His genius we saw, and praised; but it was deplorably sunk in the mire of Cockneyism (4).

Although having never corresponded to Keats (not surprising as she was only fourteen when he passed away), Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a staunch believer that the heavy criticism of Keats lead to adverse effects later on in his life. She detested how the “Cockney School” writers, especially Keats, had scurrilous attacks lobbed at them. Even when she later figured out the identity of one of the anonymous authors who took part in the harsh criticism was someone she respected, she still sided with Keats and said they erred in their criticism. She pitied the poet greatly for being “slain outright & inglouriously by the quarterly review’s tomahawk (5)”. As a poet herself Elizabeth Barrett Browning must have known the importance of a poet’s reputation. Keats was financially unstable throughout his life, and his all his earnings came from his poetry. In this sense, his reputation was not just his reputation, but also his living. Seeing a fellow poet slandered caused a justifiable outlash in several of Browning’s letters.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning could see that people did not recognize Keats’ genius. To Browning, Keats was a “grand exception from among the vulgar herd of juvenile versifiers. (6)” Keats was “a seer… Who [wrote] the things you were speaking of yesterday. (7)” He was too ahead of the times to really be appreciated at the start of the nineteenth century. To Browning, the world did not deserve such a prominent and determined poet as Keats. She notes “as singers sing themselves out of breath, he sang himself out of life (8).” Keats put every last ounce of effort into crafting his work, and nowhere was a similar sentiment expressed by his ignorant critics. According to Browning, “Nobody who knew very deeply what poetry is… could draw any case against [Keats]” (9). Keats’ critics did not hold the intellectual ability to truly appreciate his work, making their criticism against the poet inevitable. Browning felt that Keats’ critics’ imaginations could not allow them to ever dream up what Keats, “a poet of the senses” could (9). The dream expressed in “Eve of St Agnes” or anything else so creatively imagined was simply not accessible to their closed minds. Those who criticized Keats were unable to attain such “senses idealized” (9). To Browning, Keats was simply “a fine genius, – too finely tuned for the gross dampness of our atmosphere. (8)”

That Elizabeth Barrett Browning shouted such praise for someone she did not know personally might seem strange and surprising. That said, Browning had definitely become knowledgeable about his work as numerous references to Keats’ writing are sprawled throughout her letters. Robert Browning had a period where he would read Keats to a sick friend every two days, so his work was definitely present in Elizabeth’s life. But still, she never knew him personally (10). Browning’s literary circle did help fill in some knowledge of Keats’ personality, but ultimately, she was left to judge Keats based on his work alone. Sadly, this means that the connection between Keats and Elizabeth Barrett Browning was solely Elizabeth’s posthumous praise for and defense of Keats. The strength of her defense speaks to the genius of Keats’ writing, and how great writers have the potential to influence and inspire and communicate even after their deaths.

To sum up, Elizabeth Barrett Browning felt as if there were already enough burdens weighing down on Keats’ life without the criticism, as the poet’s life leads one to experience “wearing anxieties” regardless of how one’s work is received. Yet sadly Keats died before his work was honored; consequently, this makes Browning ask whether praise is necessary, and even if Keats would have been jealous of the future fame of his works. Browning obviously cannot ask for Keats’ answer, but she dreams something akin to this: Praise would just be “redundant to his content” that Keats got from the joy of creating and the “exercise of art” (11). There is comfort in such thinking.

Numbered Sources

- Wilson, John. “Review of Keats’s Endymion.” Quarterly Review, Apr. 1818, pp. 204–208.

- Lockhart, John. “Endymion Review.” Quarterly Review, Apr. 1818, p. 524.

- Shelly, Percy. “Preface.” Adonais, Methuen & Co., 1821, pp. 3–4.

- Wilson, John. “Lord Bryon and His Contemporaries.” Blackwood Magazine, 1828, pp. 403–404.

- Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 866.” Received by Mary Mitford, 26 Oct. 1841, London.

- Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 1672.” Received by John Kenyon, Aug. 1844, London.

- Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 2025.” Received by Robert Browning, 7 July 1846, London.

- Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 1029.” Received by Benjamin Haydon, 20 Oct. 1842, London.

- Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 2025.” Received by Robert Browning, 7 July 1846, London.

- Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 4252.” Received by Anna Brownell Jameson, 5 October 1858, Paris.

- Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 1829.” Received by Robert Browning, 3 Feb. 1845, 50 Wimpole Street.

Additional Sources

Keats, John. John Keats. Edited by Elizabeth Cook, Oxford University Press, 1990.

Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 4252.” Received by Anna Brownell Jameson, 5 October 1858, Paris.

Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 2472.” Received by Robert Browning, 7 July 1846, London.

Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 2025.” Received by Robert Browning, 7 July 1846, London.

Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 1706.” Received by Mary Mitford, 3 Sept. 1844, London.

Browning, Elizabeth. “Letter 1105.” Received by Mary Mitford, 30 Dec. 1842, London.