By Michael Tilby, PhD, Selwyn College, Cambridge, UK

And why shouldn’t Balzac have a beard?

EBB to Mary Russell Mitford, 11 February 1845

On my tombstone may be written ‘ci-gît the greatest novel reader in the world’

EBB to Henry Fothergill Chorley, [10] March 1845

Michael Tilby, PhD, at the Armstrong Browning Library

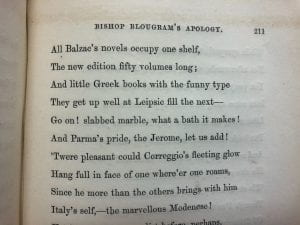

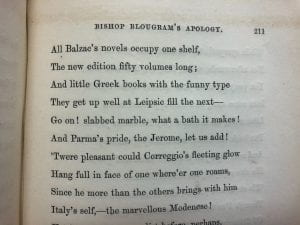

The extremely productive and enjoyable month I spent as a Visiting Fellow at the Armstrong Browning Library (ABL) was devoted to researching the response of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning to the works of the French novelist Honoré de Balzac, whom they never met in person but read avidly. The declaration in Bishop Blougram’s Apology ‘All Balzac’s novels occupy one shelf/The new edition fifty volumes long’, which would later be cited by various writers and essayists concerned to advance Balzac’s literary reputation in Victorian England, harked back to an ambition the Brownings had harboured from early in their Italian sojourn and which EBB described to Mary Russell Mitford in her letter of [4] July 1848: ‘When Robert & I are ambitious, we talk of buying Balzac in full some day, to put him up in our bookcase from the convent–if the carved wood angels, infants & serpents shd not finish mouldering away in horror at the touch of him. But I fear it will be rather an expensive purchase even here,’ though, for all their obvious humour, her words are also illustrative of a readiness to relish Balzac’s reputation as a dangerous or forbidden author, most of whose works had indeed been placed on the Papal Index.

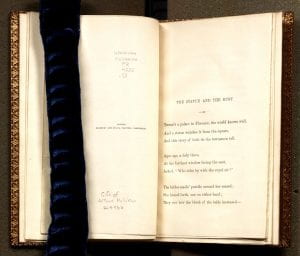

Lines 108-109 of Browning’s “Bishop Blougram’s Apology” from Men and Women, Chapman and Hall, 1855. ABL Rare Collection X821.83 P7 C466m v. 1.

The Brownings’ fascination with Balzac’s works, initially conceived and pursued independently and then, following their engagement and marriage, jointly, has long been recognized by Browning scholars, receiving, for example, relatively detailed illustration in Roy E. Gridley’s helpful ‘chronicle’ The Brownings and France (1982). As a Balzac specialist, my concern has been to analyse the phenomenon from a complementary perspective, examining it less in respect of the bearing it has on an understanding of RB and EBB’s poetic principles and practice and more in relation to the reception of Balzac in nineteenth-century England. From this perspective, the Brownings’ reflections on their reading of the French author are of exceptional interest. Although caution is needed with regard to the impression sometimes given that they had read most, if not all, of what Balzac wrote, the number of his novels they are known to have read may justly be considered uncommonly high. What makes their position unique is the prominence they accorded to discussing their reading of them. This, at a time when the paucity of translations of his work meant that many English readers were more likely to have read accounts of Balzac in the periodical press than actually to have read examples of his work. Although the Brownings were not alone amongst Victorian literati to possess a more or less adequate reading knowledge of French, they can be seen to demonstrate a rare appreciation of Balzac’s creative disregard for linguistic and literary norms. If Aurora Leigh’s confidence ‘I learnt my complement of classic French /(Kept pure of Balzac and neologism)’ may fairly be regarded as an instance of her creator in strictly autobiographical mode, it was indirect acknowledgement by EBB of how far her familiarity with the French language had developed since the equivalent stage in her own linguistic education.

From the perspective of Balzac studies, consideration is needed not only of what the Brownings did read but also of the French author’s works they appear not to have read and of which they may even have been unaware, though the absence of reference to such titles in the letters of theirs to have survived does not constitute categorical proof. That notwithstanding, the construction on that basis of a list of EBB’s Balzac reading, at least, contains both some surprising inclusions and some surprising omissions, at the level of individual titles and category alike. Tracing their reading of his work in both cases reveals its essentially haphazard nature. Awareness of his writings was acquired unsystematically and was dependent on chance mentions in the periodical press or the personal recommendations of others. Obstacles to knowledge were sometimes encountered, if only temporarily, as a result of Balzac’s partiality for re-naming his novels and stories in subsequent editions. Regardless of whether or not the original title was retained, later editions invariably represented revised versions that were sometimes significantly expanded. Works were read as and when they proved available. The two enthusiasts for Balzac were subject to the vagaries of booksellers and the proprietors of circulating libraries. Although some of his titles were serialized in newspapers to which the Brownings had ready access, others appeared in organs that were less accessible.

Still more importantly, coming to the enquiry from a position of familiarity with Balzac’s oeuvre encourages analysis that goes beyond the reproduction of comments which, when considered in isolation from the individual work that provoked them, largely restricts their import to an illustration of the extent of the Brownings’ enthusiasm for the author and the overall importance they assigned to his writing. A more analytical assessment, rooted in a concern to pinpoint further, more specific, levels of significance, requires recognition of the remarkable diversity of Balzac’s compositions. There is no one comprehensively typical Balzac novel. There is therefore a need to take into account the particular characteristics of the form and subject matter of the composition in question and the weighting of its various compositional elements, with attention paid to potentially relevant factors in the work’s genesis and the novelist’s advertised intentions, both internal and external to the text. Also pertinent to the discussion is the extent to which the novel or story is to be seen as distinctive or typical when viewed in relation to the author’s oeuvre as a whole. Rather than treating a single observation as if it were a considered, not to say definitive, judgment, it is more appropriate to see it as part of an unfolding discussion in need of chronological reconstruction. In this way, the various pronouncements acquire significance from the position they occupy on a scale running between, on the one hand, continuity and, on the other, tensions or contradictions. Ultimately, it is a question of also bringing into play what RB and EBB do not say. Their preferences within his disparate oeuvre, the works they come to prioritize, provide, in other words, instructive pointers to what they find significant or important in his writing,

At the same time, the importance of a reflection on the status of the documentary evidence became increasingly clear as my research progressed. At one level, it is simply a matter of identifying errors or misunderstandings committed by the Brownings or by one of their correspondents or acquaintances. More important, especially with regard to the predominance of letters from EBB, is to recognize the imbalance (and potential distortion) stemming from the lacunary nature of the correspondence and, as is the case with the exchanges between RB and EBB, the transition from letters to oral discussions that survive, if at all, only in the odd reference in a letter to a third party. As with all correspondence, the tone and content of the remarks will reflect a degree of sensitivity to the identity and character of the recipient. (This is separate from the absence of letters containing reference to Balzac from certain other figures who had strong opinions both for and against his worth as a writer; of these the acerbic Thomas Carlyle is one likely to have communicated his view of Balzac to RB particularly forcefully, whether by letter or face-to-face.) This leads to the most important factor of all, namely that these letters are not embryonic critical essays designed for publication. The reflections on Balzac they contain, especially those of EBB, are the responses of readers rather than critics, even if it can be shown that they were often provoked by views disseminated by the literary critical fraternity.

Following on from that observation, two further forms of context are essential in determining the significance of the Brownings’ assertions on the subject of Balzac. Together they take us beyond the realm of personal literary preferences and allow their cult of Balzac to be seen as part of the wider picture of the reception of Balzac in Victorian England. The first is the Brownings’ commitment (echoed by Mary Russell Mitford) to assessing Balzac’s novels in relation to those of a group of other novelists regarded as belonging, with Balzac, in a ‘new school of French literature’, namely George Sand, Victor Hugo, Eugène Sue, Alexandre Dumas, Frédéric Soulié, Jules Janin, and Charles de Bernard. EBB strode into an already established debate as to whether Balzac or Sand was the greater writer. There is evidence to suggest that in the 1830s and 1840s in England Sand was the more highly acclaimed of the two. She certainly appears to have been the more popular. Writing in 1844, G.H. Lewes reported that he had been told by a prominent foreign bookseller in London that scarcely a day passed without his being asked for a work of Sand’s, whereas Balzac’s works, with the exception of his latest title, were rarely asked for. There exist statements by EBB that, if taken in isolation and at face value, provide strong support for Juliette Atkinson’s contention, in her magisterial 2017 study French Novels and the Victorians, that the author of Aurora Leigh placed Sand above Balzac, but it can also be argued that the totality of EBB’s remarks on the question, expressed over a period, betray a certain hesitation and ambivalence, and that the nature of her engagement with Balzac’s writing was such as to imply a recognition of his greater importance.

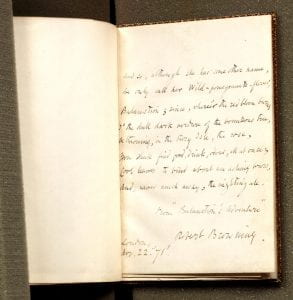

Letter from EBB to Mary Russell Mitford, dated 11 February 1845. Original housed at Wellesley College, Margaret Clapp Library, Special Collections.

The second of these two additional contexts, of which the first was, in fact, a consequence, was constituted by the assessment of Balzac’s writings in critical essays and reviews in the English periodical press, principally George Moir [Bussey], John Stuart Mill, John Wilson Croker, Henry Fothergill Chorley, G.W.M. Reynolds, G.H. Lewes, and Jules Janin, together with certain authors of unsigned articles who remain to be identified. (Some of these essays and reviews are widely known, but others have not previously been adduced in relation to either the Brownings or the reception of Balzac in Victorian England.) Although some of the journalist-critics in question aspired to the title of aristarch, the articles were not universally negative. In some cases, it is possible to detect instances of a particular essay shaping EBB’s responses, even if her evaluation of Balzac ended up being diametrically opposed to that of the critic in question. Atkinson has perceptively noted that EBB tempers her laudatory assessment of his work by appending what one might term a ‘moral health warning’ that retains from Balzac’s contemporary English denouncers elements of their outrage, but I am inclined to go beyond seeing this as either genuine queasiness or an expedient attempt at disculpation (with reference to a verbal sketch of Alfred de Musset EBB sent to Mitford in 1852, Elisabeth Jay, in British Writers and Paris 1830-1875 (2016) speaks of her managing ‘the neat trick of maintaining her reputation for moral probity […] by providing a brief coda of disapprobation to her salacious inventory of gossip’) and argue for its being part of a thinly disguised delight in the very ‘wickedness’ of the majority of his novels. At the same time, with reference to Balzac, Charles de Bernard and Soulié, she insisted, in her letter to Mitford of 11 February 1845: ‘if you had not a pleasure just as I have, in abstract faculty & power, you would not bear one of these writers…& scarcely one of their works.’

*****

My research has focused on four main areas as follows:

1. RB’s early works and Balzac’s philosophical fictions

2. EBB and Mary Russell Mitford as readers of Balzac

3. RB and EBB’s shared interest in Balzac

4. RB and Balzac: the later years

1. RB’s early works and Balzac’s philosophical fictions

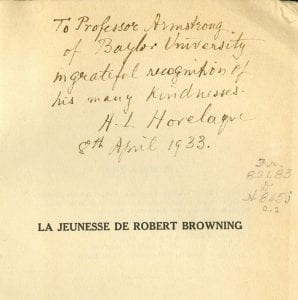

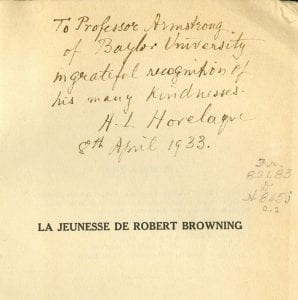

Manuscript inscription to Dr. Armstrong in the presentation copy of Henri-Léon Hovelque’s La Jeunesse de Robert Browning. ABL Foreign Languages Collection Fr 821.83 D H845j.

It has proved profitable here to re-open the question of Balzac’s Louis Lambert as a significant element in the genesis of Pauline, starting from a re-consideration of the claims made in 1932 by the Belgian academic Henri-Léon Hovelaque. That these should have been given short shrift by subsequent Browning scholars is understandable in the light of the demonstrable shortcomings in Hovelaque’s presentation of his thesis. His fundamental belief is nonetheless supported by certain observations contained in a previously unidentified nineteenth-century lecture that was obscured from view by the combination of an incorrect attribution and the absence of bibliographical information, though, in turn, some of that author’s suggested textual parallels harking back to Balzac’s are invalidated by dint of being additions Balzac made to his text after the publication date of Pauline. It has also been necessary to revisit, in context, RB’s assertion, made to Ripert-Monclar in 1835, that he did not know Balzac’s work as well as he would have wished. The rehabilitation of Louis Lambert in this connection does not however invalidate the relevance that RB’s editors are inclined to accord La Peau de chagrin in relation to the poem. The discovery of a hitherto unrecorded unsigned review of Pauline can be used as additional support for their view. This leaves the question of how Browning became aware of La Peau de chagrin (1831). His personal contact with his uncle, William Shergold Browning, in Paris and his French tutor in London are possible sources of information. In the case of the former, his neglected miscellaneous writings betray a certain awareness of contemporary French writing, though they contain no reference to Balzac. There are grounds on which to consider also John Stuart Mill, whose close engagement with Browning’s poem in preparation for a review that never reached publication was accompanied by an early interest in all things French. (Although the author of Pauline may not have known Mill personally at that point, he was an intimate of W. J. Fox and Eliza Flower.) Above all to be taken into account, though, are various accounts of La Peau de chagrin that had appeared in the English periodical press immediately prior to the composition of RB’s poem. Certain textual details of RB’s poem can likewise be shown to echo at least one of Balzac’s contes philosophiques from the same period, while Paracelsus parallels the same author’s frequent mentions of the physician and alchemist.

2. EBB and Mary Russell Mitford as readers of Balzac

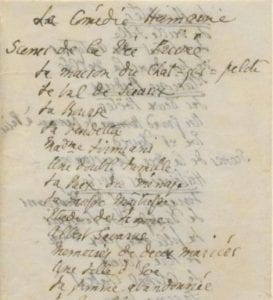

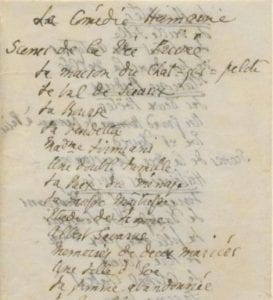

EBB’s handwritten list of Balzac titles appended to her letter to Mary Russell Mitford, dated 8 February [1847]. Original housed at Wellesley College, Margaret Clapp Library, Special Collections.

As indicated above, my concern here is to analyse in detail this unique exchange of letters both chronologically and in context in order to tease out the significance of the way Balzac is viewed by the two correspondents and how it evolved over time from initial doubts and even hostility to a shared passion that was nonetheless able to accommodate temporary instances of dissension. This evolution, in which

Le Père Goriot was a watershed experience for EBB, requires also to be seen against shifts of emphasis in their allegiance to the principal French rivals for their admiration. In addition to re-evaluating the elements of moral disapprobation and highlighting the piecemeal way in which they acquired familiarity with Balzac’s writings; the interaction of their discussion of their reading with the critical reception of his work in early Victorian England; and their concern to rank Balzac, Sand and their contemporaries in order of importance, the aim has been to identify the elements of Balzac’s writing to which they were particularly drawn. Thus, notwithstanding their (and especially EBB’s) self-confessed, though unrealized, desire to read his entire oeuvre, they were especially enthused by the many works of his in which a major concern was with writers (or journalists), creative genius, or the predicament of single women, themes which were not infrequently interwoven.

Draft MS of EBB’s translation of a poem (‘Chant d’une jeune fille’/’The Song of a Young Girl’) ascribed to the fictional poet Canalis in Balzac’s Modeste Mignon. D1204.

Of particular significance in the case of each correspondent is her reaction to reading Béatrix (featuring a character obviously modelled in part on George Sand), Modeste Mignon, the tripartite Illusions perdues (with, in the second part, its notorious attack on journalists which was at the root of the subsequent spat between Balzac and Janin) and the first three parts of its sequel, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, which presented the eagerly awaited answer to the question of the destiny of the failed poet Lucien de Rubempré. In addition to providing a portrait of another poet of questionable merit, Modeste Mignon featured in its eponymous heroine a character who sets to music a poem that EBB would translate into English, a draft of her version being preserved in ABL. This requires to be related to the discussion in these letters of translating Balzac and, indeed, of his ‘untranslatability’. Especially noteworthy, in a wider context that is dominated by moral anxiety, is the responsiveness of EBB and Mitford to Balzac, George Sand, and Victor Hugo’s creative extension of the possibilities of the French language, though it would be to RB that she would most eloquently express Balzac’s pre-eminence in this regard. At the same time, a would-be complete appreciation of these letters needs to acknowledge that on a personal level, the reading of Balzac for EBB and Mitford was a prism through which to create a sentimental relationship sustained by the cultivation of a shared sense of moral boldness and linguistic and cultural superiority. Every opportunity was seized by them to drop the name of ‘our Balzac’, or some such phrase, even in contexts unlinked to him or his works. The picture is further completed by consideration of Mitford’s observations on Balzac in letters to others and in her 1855 volume of reminiscences.

3. RB and EBB’s shared interest in Balzac

First installment of Béatrix in Le Siècle, 13 April 1839. Available online via Gallica.

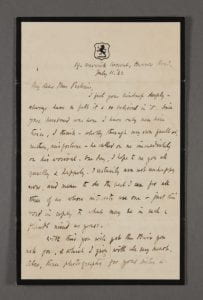

The first concern here is to establish the extent to which RB, like EBB, developed a familiarity with Balzac’s novels prior to their relationship. In the years after the publication of Pauline and Paracelsus, he eagerly followed the serialization of the first part of Béatrix in Le Siècle in 1839, though it was the initial chapters describing the small Breton town of Guérande and its environs that exerted a particular attraction. He would have been unaware, however, that the version he was reading had been doctored out of respect for the susceptibilities of a mass audience. It may be that he read in this format some or all of the other works of Balzac that were serialized in the same newspaper. There is, on the other hand, no trace of his having read the short story Un drame au bord de la mer (1834), which was set in the same area in Brittany and offered the added interest of employing Louis Lambert as narrator. Unlike EBB, RB showed no sign of wishing to proselytize with regard to Balzac’s compositions; it was Hugo’s work in this period that he pressed upon the attentions of Alfred Domett. In the letters the Brownings exchanged prior to their marriage, Balzac is prominent and it may be assumed that discussion of works such as La Recherche de l’absolu continued during his visits to Wimpole Street. It is difficult to imagine EBB not being as wide-ranging in her later references to his work as she was in her letters to Mitford. Balzac’s pre-eminence in their estimation was bolstered by the fact that RB did not share his wife’s admiration of Sand, though his objections to Consuelo were not phrased in the reprehensible language to which Carlyle had recourse when denouncing her writings a few years previously. He was quick to pick up on any reference to Balzac in the press, especially hostile mentions in English literary periodicals, and was keen to read any work of his, whether new or less recent. And only partly out of knowledge that this was guaranteed to please EBB and provide a fertile topic of conversation. Although textual evidence is relatively scant for the years separating their departure for Italy and EBB’s death, it is clear that both continued to read Balzac’s novels and remained committed to making them fundamental reference points in their discussions, though it was probably EBB who ensured that this was so. This was in spite of obstacles in the way of reading Balzac in Italy that were both logistical and the result of censorship. Their shared interest in the writer and his work was kept alive by several expatriate residents or visitors who had either known him or were keen to share their own interest in him. The most easily documented example is that of Margaret Fuller Ossoli. The Brownings’ joint reading of Le Cousin Pons in 1850 merits particular attention. EBB reported that they were both greatly affected by Balzac’s death a few months’ later, an event that deprived them of making his acquaintance during their Parisian sojourn of 1852, when, however, they attended one of Sand’s ‘evenings’. At the same time, there are signs that, to a certain extent, they employed different yardsticks in their assessment of Balzac as a creative artist, though this can only have served to provide a basis for stimulating debate. The view frequently advanced that, following their reading of Madame Bovary in 1858, Balzac was toppled from the pedestal on which RB had placed him nonetheless invites qualification.

4. RB and Balzac: the later years

Page from the opening chapter of the first edition of Béatrix containing references to Guérande, Batz, and Le Croisic. Available online via Gallica.

The principal focal point in this period is RB’s discovery of the area of Brittany that Balzac had immortalized in Béatrix and which he himself went on to celebrate in The Two Poets of Croisic (1878). The same place names are present in both works: Guérande, Batz, and Le Croisic. A closer comparative study of the two works can certainly be envisaged, though Balzac recalls druidic monuments in other of his works of fiction as well. There is no reason to challenge Mrs Orr’s statement: ‘His [RB’s] allegiance to Balzac remained unshaken, though he was conscious of lengthiness when he read him aloud.’ An entry in Evelyn Barclay’s Venice diary a month before RB’s death records a visiting French art historian and historian of literature professing that ‘he had never met any one, who had such a deep and thorough knowledge of french literature’ before going on to state categorically that RB’s ‘favourite french author was Balzac.’ It is notable that RB’s later works, e.g. The Inn Album and Red Cotton Night-Cap Country, stimulate such author-critics as Swinburne, Stevenson, W.E. Henley, John Addington Symonds, Arthur Symons, Saintsbury (in the 1911 edition of Britannica) and Gerard Manley Hopkins (albeit with regard to the opening of The Ring and the Book in a comment that was unflattering to both writers) to propose parallels with Balzac’s novels, while the forgotten minor French poet, Charles des Guerrois, who translated poems by both RB and EBB, stands out by virtue of his claim in 1885 that ‘Aurora Leigh me fait penser par moments à notre Balzac.’ (The previous year an Italian critic had emphasized the Balzac-like detail of RB’s descriptions.) Although the probing of such affinities lies outside the scope of my study, certain shared characteristics suggest themselves for further consideration, amongst them a positive form of prolixity and a penchant for neologism and stylistic hybridity, together with an intellectual and cultural eclecticism that results in evocative bric-à-brac or clutter and poses interpretative difficulties of an epistemological nature. Also ripe for further comparison are the effects created on occasion by each author’s embedding of a central narrative in a related secondary one.

*****

Literary-historical research invariably has unintended consequences. In my case, a fascination with the French novel in Pen Browning’s French Abbé Reading at the top of the staircase at ABL resulted in an additional project that has continued on my return from Baylor in the form of an article with the working title ‘Pen Browning’s French abbé revisited.’

French Abbé Reading by Robert Barrett Browning, 1875. Armstrong Browning Library.

*****

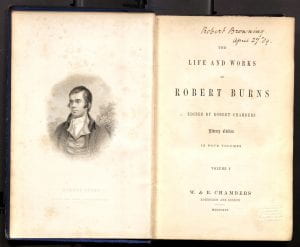

My research at the Armstrong Browning Library was made possible by the award of a Visiting Research Fellowship funded by Baylor University. It is with pleasure that I extend warmest thanks to the Director, Jennifer Borderud, and her staff, all of whom went out of their way to ensure that my time at ABL was as enjoyable as it was rewarding. Melvin Schuetz not only brought research materials to my table with preternatural rapidity, but willingly placed his unrivalled knowledge of the collections and their history at my disposal. No question of a practical nature was either too great or too trivial for Christi Klempnauer, who unfailingly produced information or a solution with the warmest of smiles. It was a privilege to be able to work undisturbed in such comfortable surroundings. Immediate access to key works and the remarkable Wedgestone online edition of The Brownings Correspondence (including content not generally available) made for extremely efficient working practices, especially for someone new to the bibliography. As for the richness of the specialized holdings, I was able to make a number of related discoveries that would not have been possible in any other single library. A supplementary pleasure was afforded by an awareness of the provenance of certain volumes, especially those that had been presented by their author to Dr Armstrong. Along with all other Visiting Fellows, I imagine, I felt it was incumbent on me to end up producing a study that he would have approved of. Since my return, Philip Kelley has shown great kindness in revealing to me not only the facts behind an enigmatic 1961 newspaper report of the discovery of a Pen Browning painting that turned out to be his portrait of Joseph Milsand and which is now in ABL, but also the extraordinary story of his own involvement in establishing the sitter’s identity and the provenance of the painting was well as keeping track of its whereabouts prior to its long-delayed appearance at auction. He has also been equally generous in drawing my attention to several items related to my main topic of research of which I would otherwise have remained unaware.

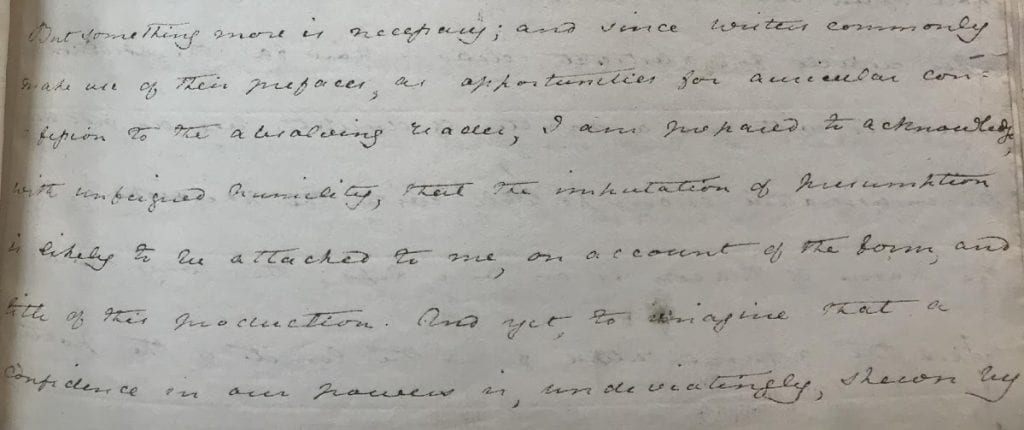

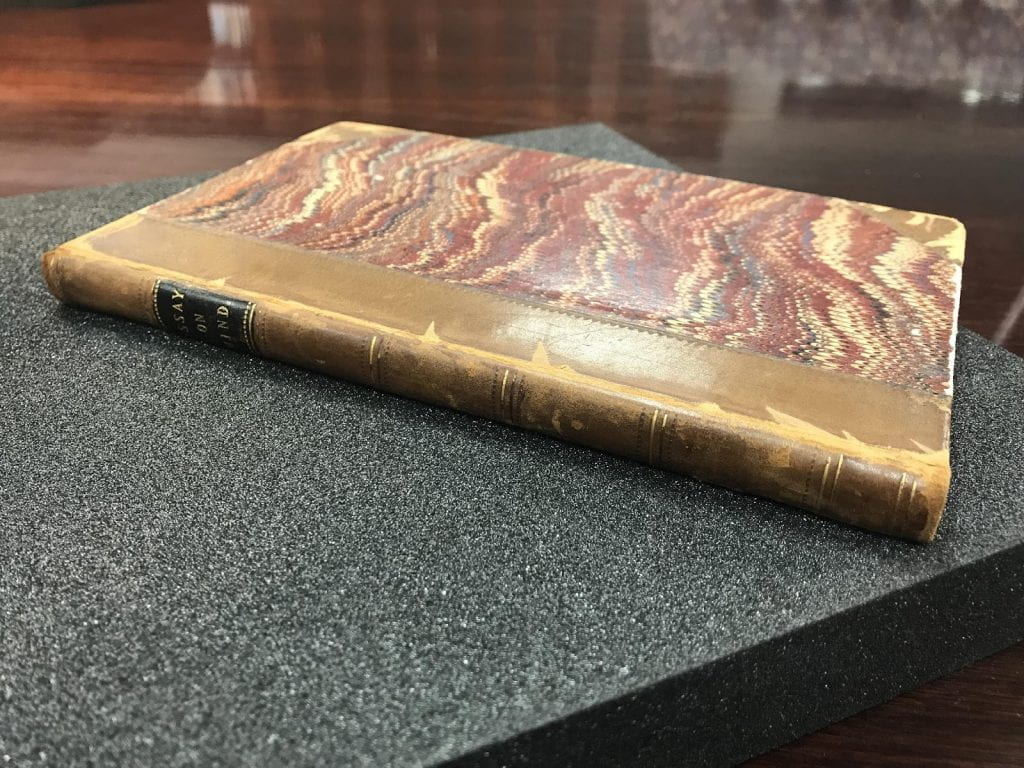

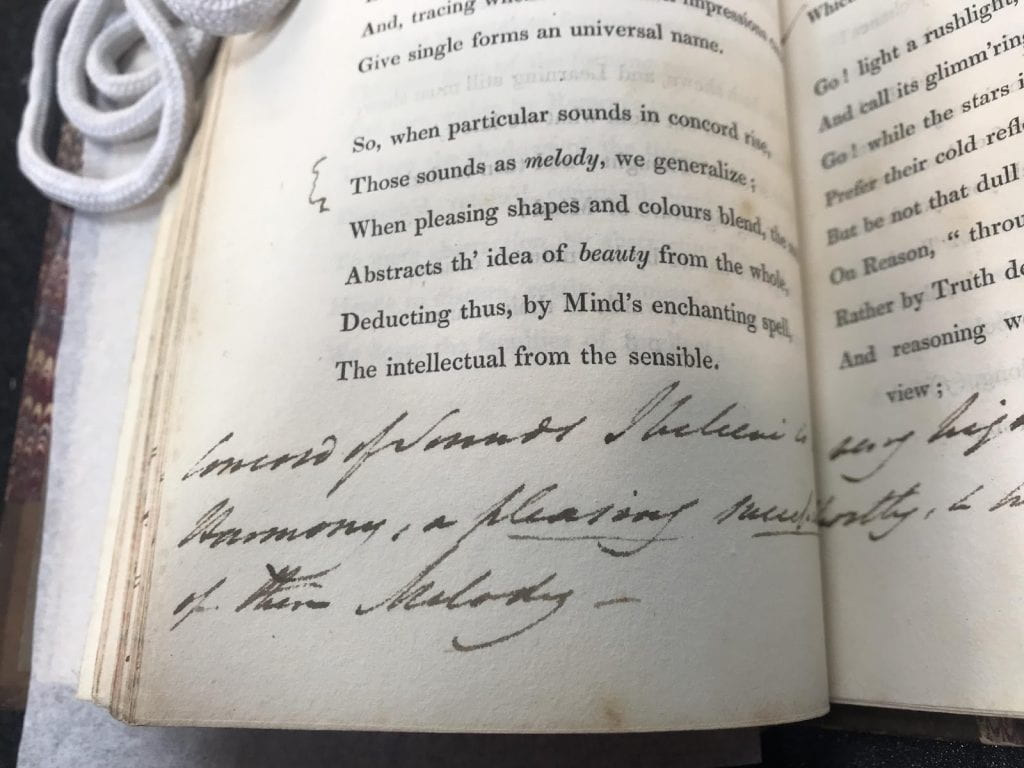

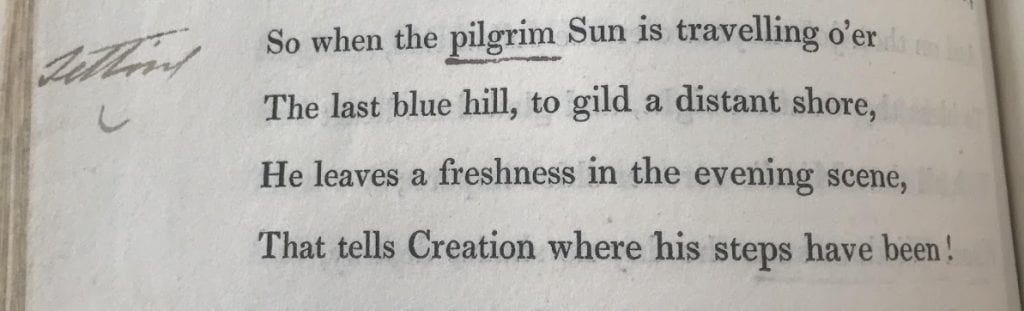

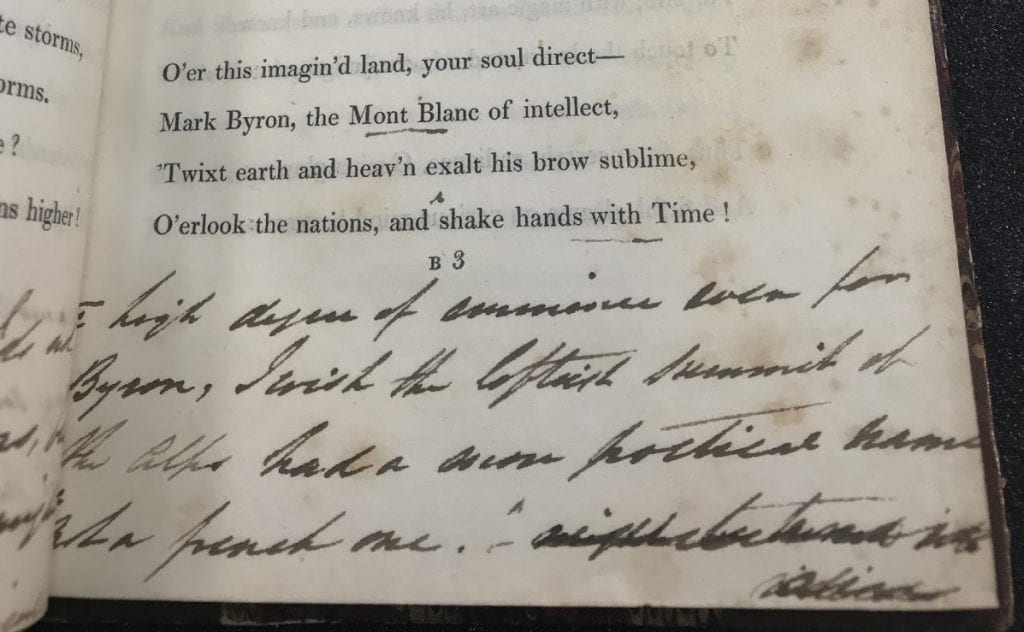

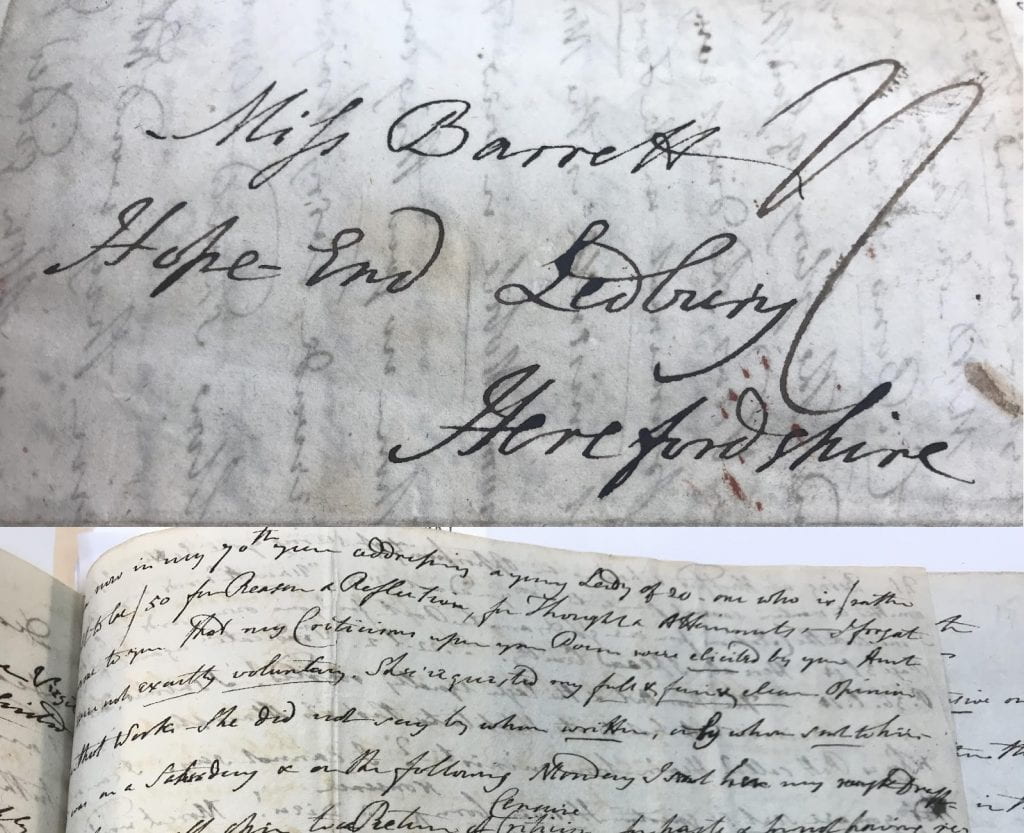

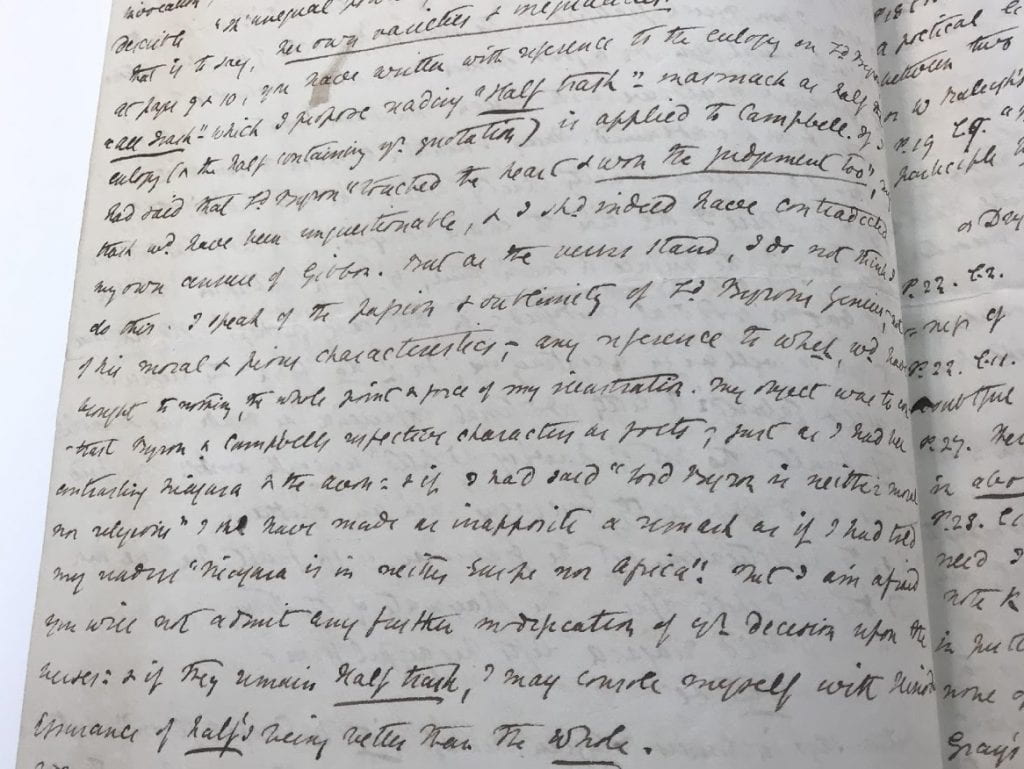

![Henry Cotes, Comments of EBB’s An Essay on Mind, [Early March 1828] (D0250))](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2019/07/image13_final-1024x345.jpg)

![Henry Cotes, Comments of EBB’s An Essay on Mind, [Early March 1828] (L0080.1) and Elizabeth Barrett to Henry Cotes, March 8, 1828 (D0250)](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2019/07/image1516_final-1024x842.jpg)