Nearly all of the 178 seats in the screening room at Baylor’s Mayborn Museum Complex were filled on the afternoon of June 10th as community leaders and interested citizens gathered to watch A Place at the Table, a new documentary film directed by Kristi Jacobson and Lori Silverbush—makers of Food, Inc. It examines the problem of food insecurity in the United States, and the inherent paradox that 50 million Americans regularly go hungry even though the U.S. produces and imports more than enough food to prevent hunger. The event also featured a panel discussion with Cheryl Pooler, a social worker and homeless liaison for Waco ISD, Dr. Gaynor Yancey, professor at the Baylor School of Social Work, and Matt Hess, executive director of World Hunger Relief, Inc. Shamethia Webb, the regional director for the Texas Hunger Initiative – Waco office, moderated.

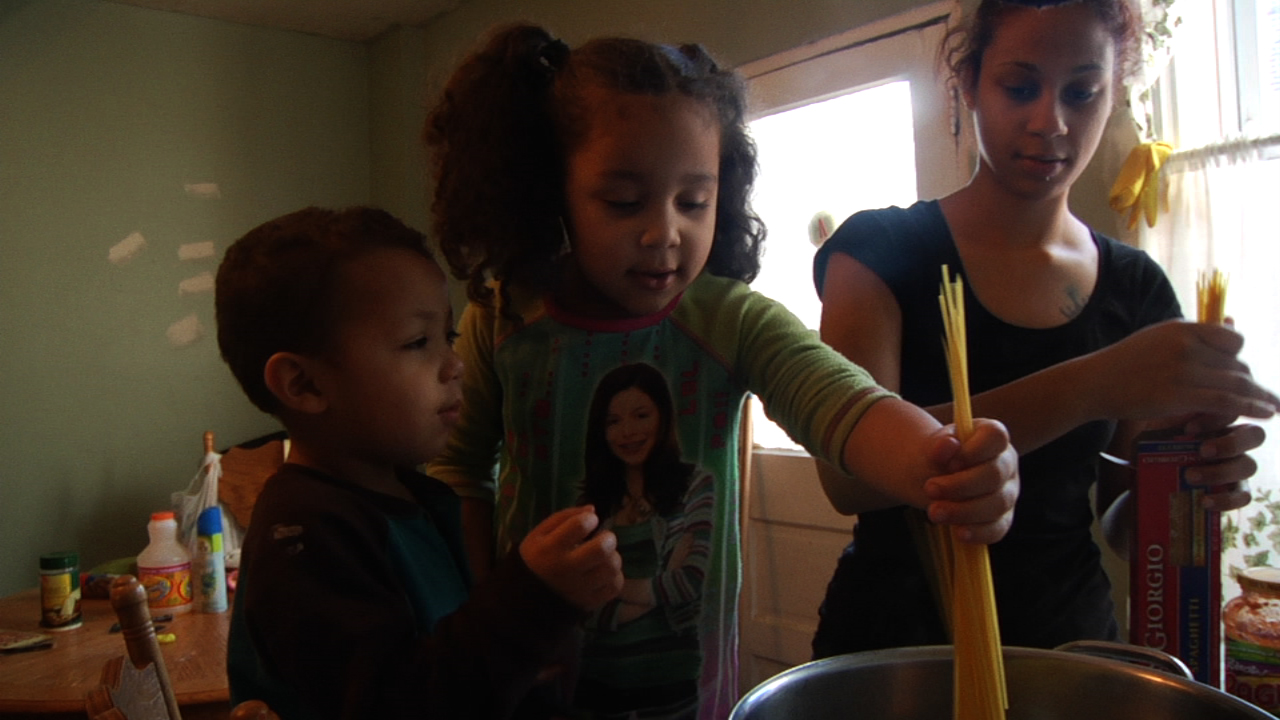

A Place at the Table shows the daily lives of families suffering from hunger. Barbie lives in Philadelphia with two young children, one of whom suffers from developmental difficulties due to malnutrition. She struggles to provide enough for them to eat on her part-time pay and has been forced to put off attending college because she cannot manage without this meager wage. In Collbran, Colorado, fifth-grader Rosie lives in a three-generation home where she and her siblings sleep on the floor of a combination pantry/laundry room and depend on her teacher and the local church to provide her family with enough to eat. In rural Mississippi, Tremonica, age eight, is obese because her mother only has access to low-quality processed food, as the nearest market selling fresh produce is over 60 miles away.

Interspersed within the stories was a narrative just as outrageous as the hunger these people were experiencing—that of a catastrophically broken food economy. As noted in the film, the expansion of federal nutrition and anti-poverty programs in the mid-1970s nearly succeeded in eliminating domestic food insecurity. By 1980, however, changes in agricultural policy—specifically changes in farm subsidy payments—created a radical shift in the flow of tax benefits to farms. The government began diverting billions of dollars in crop subsidies to companies that grew ingredients for processed foods, which in turn resulted in a steep decline in prices for these nutritionally inferior yet readily available products. In the meantime, the loss of subsidies for growers of less-profitable fruits and vegetables caused prices to increase. The trend continues in the Farm Bill currently being debated in Congress, with a majority of subsidies going to corporate producers of feed crops and processed food ingredients like high-fructose corn syrup, wheat, and sugar.

At the same time that food policy was changing, Congress began large cuts to the social safety net. Millions of households were dropped from government assistance and had to struggle even harder to avoid going hungry while the national attitude towards the poor became increasingly hostile and the stigma of being on government assistance grew increasingly negative.

Indeed, it seems that the greatest barrier to re-examining and re-implementing anti-poverty and anti-hunger policies is the assumption that poverty is necessarily a result of moral failure. Whenever the issue of expanding the social safety net is brought up, two rebuttals are often employed: cost* and the anxiety that someone might get assistance that we don’t think they deserve.

The myth that people can comfortably sponge off of public assistance was given a stark debunking in the film: the average SNAP benefit is around $4.25 per person per day. Rep. Jim McGovern of Massachusetts shared his story of taking the SNAP Challenge—an initiative begun by the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) that asks elected officials to live on the average allotment families receive in SNAP benefits; in just one week he found himself struggling to function on the pittance of calories that $4.25 per day can buy. Add to this the stress of having school-age children and working physically demanding jobs, and you have a recipe for malnutrition and failing health. And yes, these people are working: according to a USDA report, in 2009 85% of food-insecure households had a working adult (this does not account for households where all members are retired or disabled).

But can’t private charity solve the problem? A Place at the Table shows how unrealistic this expectation is. While community groups and religious centers have an important role to play, they lack the resources and infrastructure to meet widespread need. Since 1980, the U.S. has gone from having 400 food pantries to 40,000 yet this expansion has failed to slow the growth of food insecurity. These organizations often struggle to maintain resources and volunteers sufficient to combat hunger in their communities. The film introduces us to a pastor in Collbran, Colorado who drives out of town twice a week to get four pallets of groceries from the food bank (as much as his trailer will carry), which is given to needy families in the area, and it still isn’t enough. Local charitable action is essential, but charitable institutions will be fully able to meet the high level of need when in collaboration with generously-funded federal nutrition programs.

So why does a nation as wealthy as ours, that produces as much food as we do, continue to put forward policies that subvert programs like SNAP that are known to be effective? The problem is two-fold: ideology and empathy. We are in love with the myth of the self-made man or woman. We praise those who succeed in spite of circumstance, and when we find such a person we take him or her as a rule rather than an exception. In truth, such people are exceptions. But this devotion to a meritocratic ideal is a defense mechanism used to protect us from the unpleasant truth: “There but for the grace of God, go I.” We assume our own innocence and refuse our neighbors the same courtesy. We use phantoms like the “welfare queen”—an archetype without a name or a face—to avoid being affected by the reality of human suffering. We want to believe the worst about the poor and the hungry because the only thing that stands between them and us is luck; the world does not automatically reward hard work and responsibility like a cosmic vending machine. We are afraid to acknowledge that but for a minor change in circumstance, we could be the person working endlessly to provide for our families and have nothing to show for it but an empty larder and a bare table.

This is why events like this screening are so important: they force us to put a face to the symbols, to stop talking about abstract ideas and instead talk about people with names and families and stories. And they let us know that we have the power to change how our food industry works. About a hundred and fifty people in Waco allowed themselves to be affected by the stories of Barbie, Rosie, Tremonica, and others. Policy-makers like Jim McGovern and all those who have taken the SNAP Challenge allowed themselves to be affected. And they will take those stories with them into their neighborhoods and workplaces and the chambers of Congress, more aware than ever that, as CBS correspondent Charles Kuralt said in the 1968 documentary Hunger in America that once spurred us to put an end to food insecurity, “The most basic human need must become a human right.”

* The cost argument fails, as SNAP has been shown to be an economic stimulus. An independent study by Moody’s Analytics found that every dollar of SNAP benefits spent generates $1.73 in GDP growth.

Written by: Chris Rhoton, Child Hunger Program Specialist, Texas Hunger Initiative

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures