Texas has changed quite a bit over the years, as is readily seen in our vast photograph and postcard collections. To help bring some of those changes to life, we’ve created a “Texas over Time” series of Meta Slider’s that will illustrate the construction and renovations of buildings, street scenes, and more. Our collections are especially strong on Waco and Baylor images, but look for some views beyond the Heart of Texas, too.

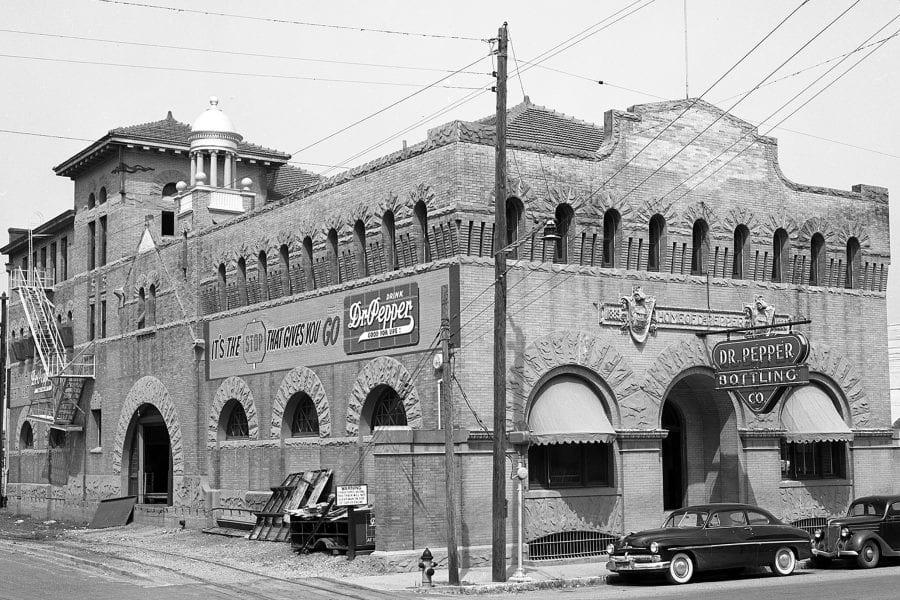

Dr Pepper Museum and Free Enterprise Institute, Waco, TX

*Dr Pepper, America’s oldest major soft drink brand, had its origins in Waco, Texas.

*The Dr Pepper Museum and Free Enterprise Institute is housed in what was originally the Artesian Manufacturing and Bottling Company. It would later become the first facility to produce the soft drink.

*This structure, located on the corner of 5th and Mary Street, Waco, Texas, was built in 1906 and designed by architect Milton Scott. Its brick walls measure 18 inches in thickness and are supported by a solid timber foundation.

1951 and 2018 Photos by Fred Marlar and GH, The Texas Collection, Baylor University

*Throughout the 20th century the building’s location on Mary Street allowed Dr Pepper easy access to shipping on the route of the St. Louis Southwestern “Cotton Belt” Railroad.

*On May 11, 1953, the structure was damaged by a large tornado that destroyed a section of the city’s central business district and caused the deaths of 114 people. The side of the building still bears the repair work done to the massive brick walls.

May 1953 and 2018 Photos by Unknown (General Slide collection) and GH, The Texas Collection, Baylor University

*The building served as the Dr Pepper Bottling Company for many years. When operations ceased at that location they moved to west Waco. In the 1980s businessmen Wilton Lanning and W.W. Clements conceived the idea to make it a museum dedicated to the soft drink, its history, and the idea of the free enterprise system. The museum opened to the public on May 11, 1991, the 38th anniversary of the tornado.

*At the time of its opening, it was viewed as a catalyst to revive that part of the downtown area. Its continued growth and success have helped Waco to become one of the state’s top tourist destinations.

Works Cited:

Ellis, Harry E., Dr Pepper-King of Beverages. Dallas, TX: Dr Pepper Co. 1986. Print.

Text and Meta Sliders by GH