By Kenna Lang Archer, instructor at Angelo State University

By Kenna Lang Archer, instructor at Angelo State University

“Why haven’t we developed the Brazos into something like San Antonio’s River Walk?”

“Sure, we have sail-gating, but when are we going to develop this river properly?”

“Why haven’t people realized the value of the Brazos and put some real money into developing it?”

Questions like these resonate along the length of the Brazos but are regularly volleyed around Waco lunch tables. If anything, the revitalization of Waco’s city center and the construction of McLane Stadium have only made these questions more pressing. Many Wacoans simply don’t understand why one of this state’s most iconic rivers has seemingly escaped the reach of developers. They cannot fathom the lack of attention. Coach Art Briles even raised this question over the summer, insisting that the lack of development is “unbelievable” and something that “blows [his] mind.” I understand that sense of shock and awe. When I began my work on the Brazos River nearly a decade ago, I approached it with the exact same question. Why, I asked, has the Brazos avoided the attention of developers? How could any businessman allow that to happen? As I began looking into the river’s history, however, I realized that I was asking the wrong question.

This belief that the Brazos River should be more heavily developed is actually very old. Stephen F. Austin introduced American immigrants into Mexican Texas in 1821, and in the nearly two hundred years since then, developers and boosters and politicians have worked almost unceasingly to improve this powerful and temperamental waterway. Even before Austin’s arrival, however, Spanish settlers and Indian populations manipulated the river, developing it for their own purposes. The Spanish, for example, built irrigation canals and small embankment dams in Texas. No, the conviction that this river should be developed is not new. The end result of development has changed, but the idea of improving this river has not. A better question, then, is this: given the long history of attention to the Brazos, why has it not been developed more fully? Why must men like Art Briles shake their heads in wonder today, mind reeling at the untapped potential of this river? Why must politicians and business leaders and the inestimable public do likewise?

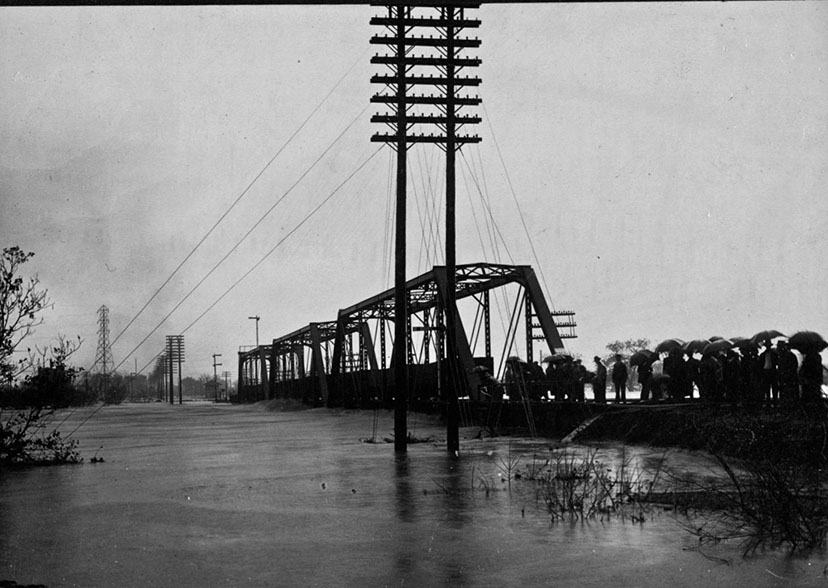

Take, for example, the lock and dam project (early 1900s). To expand navigation along the Brazos River, the Army Corps of Engineers proposed a series of eight structures that would use a small-scale dam and a lock to raise water levels in areas plagued by shoals, falls, and bars. This project was applauded energetically, but construction of the locks and dams proved to be problematic, to say the least. In 1912, for example, engineers at the lock and dam near Waco reported that an untimely drought had dried up the river, leaving a scant 8 inches of water in the lock. One year later, employees at the same lock noted that a recent flood had done more than $20,000 worth of damage (the equivalent of $481,000 today).

“Why haven’t we tried to develop the Brazos River?”

As I said, that isn’t the right question.

“Why haven’t we been able to develop the Brazos more fully?”

That question may not have an easy answer, but it does guide us down a productive path of research and discussion.

Eager to hear more about this discussion? Join us in Bennett Auditorium at 3:30 pm on Thursday, October 22, to hear her thoughts on development along the Brazos River. Dr. Archer, an instructor at Angelo State University and Baylor alumna, is promoting her book, Unruly Waters: A Social and Environmental History of the Brazos River. The book will be available for purchase at a reception following at The Texas Collection and at the Baylor Bookstore during Homecoming.