My work in information technology has paid my family’s bills for over 20 years. If I ever slow down to think (who, me?), I meander through topics surrounding the idea of how to make better use of the constant flood of information generated by all the electronics my team and I are responsible for.

Naturally I am enthralled by any studies that highlight the way our brains process all the inputs taken in by our senses of the world around us. Several different fields of study surround this idea, and the area that emerges from all this expertise and draws me in to deep fascination is the idea of “How does the same set of information lead different people to different conclusions?”

Sometimes our decision making is downright irrational. It turns out, this is a result of a defense mechanism against information overload known as cognitive bias.

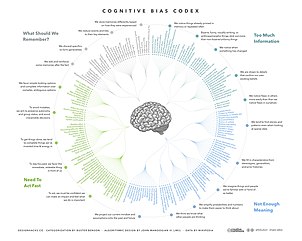

Scratching the surface, there are 100s of biases listed on Wikipedia. Fortunately, there’s a excellent summary overview put together by a fellow named Buster Benson (who works in IT, of course!). I love the work that Benson put into this rich summary. He gathers topics together into the four main problems that the brain uses these biases to address:

- Too much information

- Not enough meaning

- Need to act fast

- What should we remember?

Benson’s summary is so thick as to be itself a cause of cognitive distress, so he breaks it down even further.

- To cope with information overload, the brain strives to convert noise into signal.

- Information is less useful without meaning, so we adapt signal into story.

- We jump to conclusions to take faster action, thus story becomes decision.

- Experience helps with future decisions, so what needs to be remembered? These memories inform our mental models.

As with any hack, these adaptations have their utility but also have their limitations. Benson goes on to explain the downside.

- We tend to overfilter and miss out on important details.

- The quick jump to meaning can introduce mistaken assumptions.

- Rapid decision making can be unfair, self-serving, and counter-productive.

- By the time this imperfect process filters into memory, we tend to propagate errors into future decision making.

So what’s to be done? Being aware is the first step, and you’re already there! The next step is to embrace this new awareness with humility and respect. Understand that your own grasp of reality can be just as tenuous as the next guy’s, and let’s learn to work together towards consensus. Benson concludes with a list of some mitigation techniques (read his article; it’s fantastic!)

In conclusion, I leave you with the oeuvre d’art that came from Benson’s collaboration with a graphic designer named John Manoogian III.

(If you want to buy me a gift for no particular reason, send me one of these!)