This blog post was composed by Aaron Ramos, master’s student in the History Department.

At Baylor University, graduate students in the History Department must enroll in HIS 5370: Advanced Research and Writing. The goal of the course is to provide students with an introduction to researching in archives, the bread and butter of the historian’s craft. This spring, our professor tasked us with producing an article length project utilizing one or more of the archives on campus. LGBTQ+ history, while not my main field, is a topic I am deeply interested in. The archival holdings at the Baylor Collections of Political Materials at W. R. Poage Library, as well as the Texas Collection, lent themselves nicely to my project. The following offers a snippet of what I was able to glean through Poage Library:

Letter from Laurie Eiserloh, Executive director of the Lesbian/Gay Rights Lobby of Texas to former Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock.[i]

When thinking of watershed moments in American LGBTQ+ history, the 1990s likely do not come to mind as a decade of much importance to gay and lesbian Americans. However, the final decade of the 20th century would see LGBTQ+ Americans becoming increasingly vocal about the issues impacting their lives. Advocacy groups such as the Gay and Lesbian Political Caucus and the Human Rights Campaign helped to champion legislation that would provide legal protections and recognition for LGBTQ+ Americans in housing, labor, and the Armed Services. Another issue that weighed heavy on the minds of sexual minorities, especially those in Texas, was bias motivated violence and hate crimes.

By 1994, several gay men had been murdered throughout the state of Texas. From San Antonio, to Midland, to Tyler, the perpetrators of these murders were motivated by anti-gay bias. In particular, the murders of Paul Broussard and Fred Mangione in Houston, and Charles Resendez in San Antonio spurred advocacy groups to action in urban Texas. Broussard, Mangione, and Resendez’s murderers were all motivated by anti-gay bias. Advocacy groups referred to these murders as a symptom of a ‘hate epidemic.’[ii] The public fervor these killings generated, and the subsequent legislation they informed, were part of what one historian has referred to as the Anti-Violence movement.[iii]

This anti-violence movement would see LGBTQ+ Texans and their allies seeking to work within the state’s legal framework to ensure legal protections for gay Americans. According to an article released in the Houston Chronicle, local gay advocacy groups in semi-urban/rural Texas were also pushing for more stringent laws that listed sexual orientation as a category protected from hate crimes/bias motivated violence. Their organizing culminated in the passage of H.C.R No. 227 in 1993, which explicitly listed sexual orientation as a protected class against hate crimes. Moreover, H.C.R. No. 227 spelled out sentencing guidelines for individuals convicted of committing hate crimes and called for educational initiatives to reduce bias related incidents.[iv]

Article from the Houston Chronicle documenting local pushes for more stringent hate crime laws.[v]

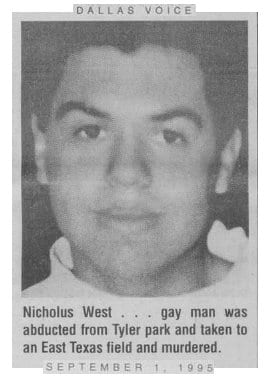

The efficacy of H.C.R. No 227 would be put to the test not long after its passage. In early December of 1993, Nicholas Ray West, a twenty-three-year-old gay man, was beaten and shot nine times in a park in Tyler, Texas. West’s murderers (three young men in their late teens) confessed that they murdered West because he was gay. Thanks to the statewide conversation on anti-violence and legal protection for gay Americans, law enforcement treated West’s murder as a hate crime, and all three men involved received capital murder charges. One received the death penalty.[vi]

Image of Nicholas Ray West (1970-1993).[vii]

While the 1990s saw discussions of LGBTQ+ rights taking place on a national level, historian Christopher Haight describes the anti-violence movement as a uniquely Texan episode in LGBTQ+ history. Advocacy groups and individuals in Texas witnessed first-hand how state legislators were unable (and at times unwilling) to protect gay citizens from violence. Their outrage then informed their advocacy, which led them to put pressure on their elected officials to ensure that Texas would be a safe place for all.

References:

[i] Eiserloh, Laurie. Bob Bullock Letter. April 20, 1993. Bob Bullock Lieutenant Governor papers, Accession #5C, Box #560, Folder #22, Baylor Collections of Political Materials, W. R. Poage Legislative Library, Baylor University.

[ii] Haight, Christopher. “The Silence Is Killing Us: Hate Crimes, Criminal Justice, and the Gay Rights Movement in Texas, 1990-1995.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 120, no. 1 (2016): 20–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44647078.

[iii] Haight.

[iv] Capitol.texas.gov. “H.C.R.227.” 1993. https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/80R/billtext/html/HC00227I.htm

[v] Sallee, Rad. “State gay-group wants tougher hate-crime law.” Jan. 17, 1993. Bob Bullock Lieutenant Governor papers, Accession #5C, Box #1047, Folder #5, Baylor Collections of Political Materials, W. R. Poage Legislative Library, Baylor University.

[vi] Haight, 37.

[vii] https://www.texasobituaryproject.org/070596west.html