Everything’s bigger in Texas, the hoary old chestnut reminds us, and no group of people understood the Lone Star State’s geographic expansiveness like the speculators who bought up acres of prime Texas land for pennies on the dollar and hoped to turn a quick profit by selling them to newly arrived immigrants and Yankees looking for a better life out West. From railroad companies to chambers of commerce and private corporations, concerns large and small poured their creative efforts into marketing the open range in publications featuring photographs, artistic renderings and glowing testimonials from satisfied customers.

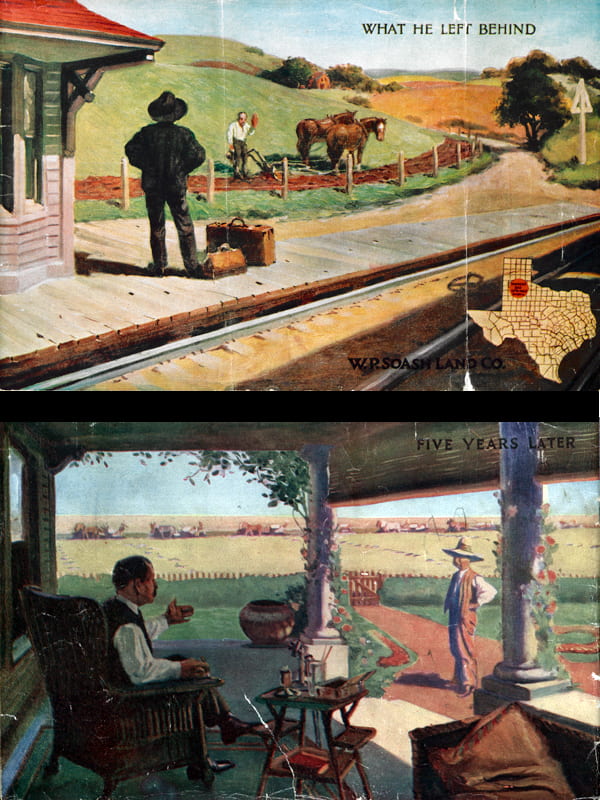

These promotional materials flooded the market with wild claims and speculative gambles dressed up as fact. From pie-in-the-sky layouts of a future metropolis on the High Plains to photos of “modern homes” offered on a dusty, unpaved street on the edge of a field of kaffir wheat, they were masterpieces of salesmanship. To an immigrant family setting foot on American soil for the first time in a major port city, surrounded by an alien culture, they must have been appealing indeed.

One of our smaller – but no less impressive – digital collections is a set of 37 promotional publications related to Texas. These items, which are held by our colleagues at The Texas Collection, tell the stories of the many ways the untamed West was broken through hard work, fast deals and dogged perseverance.

In my pursuit of making our collections more accessible and easier to browse, I was enhancing the navigation on these items this past week when I came across three promotional brochures issued by the W.P. Soash Land Co. of Waterloo, Iowa. The design work on two of the brochures was nothing remarkable, while the third was a veritable tour de force of early 20th century design including illustrations, photographs and overblown rhetoric. They tell the story of one company’s gamble on marketing land in the South Plains of Texas and boldly declare the bright future of the towns of Big Spring and Soash: “destined to be the Twin Cities of the Plains!”

The “Empire Builder”: W.P. Soash and His Company

William Pulver Soash lived a life typical of many of the newcomers to Texas in the waning years of the 19th century. Born in the Midwest, his early life included frequently moving from town to town with his father, a railroad contractor. He dabbled in carpentry and worked as a deputy United States marshal before settling on land colonization. He founded the W.P. Soash Company in 1905 and set his sights on cheap land in the Texas Panhandle and South Plains regions.

Soash sought to differentiate himself from his competitors by creating a company that would serve as an all-in-one concern. His company purchased the land and sold off its parcels directly to buyers, thus avoiding the stigma of merely serving as an agent or middle-man between the landowner and the buyer. Soash attempted to “[familiarize] himself with every feature of the business,” from studying climate reports to creating special excursion trains – dubbed “Soash Specials” – that ran passengers from the Union Pacific Depot in Kansas City through Ft. Worth and eventually to a terminus in Big Spring.

The Soash Company grew prosperous enough to justify locations in more than a dozen towns across ten states. As its reach grew, the company professed to have been “built along permanent lines and expects to always be in business.” It claimed (somewhat paradoxically) to be the “largest, most progressive and most conservative organization of its kind in the world.” As to Soash’s personal credentials, his brochure claimed that ““… it can be stated without fear of contradiction that W.P. Soash has sold more land contracts than any other man in the United States today.” In short: purchasing land from the Soash Company was a safe bet for opportunity seekers of all stripes, with a track record to match its uniformly positive claims.

Establishing a Namesake on the Texas South Plains: “Why Soash is Destined to be a Large City”

Battling perceptions of the South Plains of Texas was accomplished through the development and distribution of a series of promotional brochures focused on the “Big Springs Ranch Country” of Texas. The company had purchased some 300,000 acres of land comprised of the Big Spring Ranch and adjacent properties for $3 million in January 1909 and quickly set about hacking out smaller parcels for immediate sale.

To counter notions that this area was home only to rowdy cowboys, “untamed Indians” and arid, desert-like conditions, Soash produced a 50-page promotional booklet (“at a very large expense”) outlining the advantages of purchasing a farm or ranch site near Big Spring. The booklet contains a good overview of the company’s history, testimonials from landowners in the Big Spring area and plenty of data on climate and crop futures. A second, smaller pamphlet with similar information on the area was also produced.

For reasons of business success, the enticing opportunity to leave a lasting legacy or inescapable hubris, the company founded a town in the land between Big Spring and Lamesa and called it Soash. The company produced another booklet entitled, “Why You Should Invest In The New Town [of] Soash, Texas,” which included a series of photos depicting scenes from the “Grand Celebration of July 5, 1909.” They show a large gathering of people mingling among several completed buildings, patriotic bunting and American flags in prominent locations.

The pamphlet describes the city in expectedly glowing terms:

“Soash, the new town started a few months ago on Big Springs Ranch, is conceded by every one cognizant of conditions to have a splendid future. The new railway which this company is to build will aid materially in developing the town. Already there has been a good start made as is evidenced by the illustrations on this page. We want to tell you more of Soash, Texas, at some time in the near future.”

Soash built the Hotel Lorna (named after his daughter) and a company headquarters, and within a few months the town boasted several permanent structures and electricity service. New settlers began arriving in increasing numbers and a post office was established by the end of the year. The future seemed secure.

Ominous Silence from Rail and Sky

Warning signs mounted quickly, however. Despite repeated assurances that a railroad line from Big Spring would be laid to the city within twenty months of the city’s founding, the line never materialized. The Santa Fe Railroad instead chose to run a line through nearby Lamesa. For frontier towns of the early 20th century, access to a rail line was crucial for long term sustainability. A railroad meant crops could be exported to market and finished products imported for consumption. It meant quicker access to major cities – with all their social and mechanical innovations – and a sure way for more immigrants to arrive. And its absence from Soash was only the first of two major blows for the fledgling community.

The death knell for Soash came at the hands of something beyond human control. Despite a table in its Soash brochures showing the rainfall totals for the area as comparable to the highest producing regions of the Midwest, the South Plains experienced a three-year drought cycle beginning in 1909. This proved to be too much for the “highest examples of citizenship” to be found in the city, and the population dwindled rapidly. The town lost its post office twice – permanently in 1917 – and the site was abandoned after another drought cycle in 1917-1918.

“Conservative methods, carried out courageously, will always win.”

The “Empire Builder’s” company could not outlive the death of its namesake city. The W.P. Soash Company filed for bankruptcy in 1912, and its founder would go on to a longer career in land development after a stint in the Texas Cavalry in World War I. The site of Soash returned to the earth from which it briefly sprang, the ruins of only a bank and office building remaining to mark this once much-ballyhooed Texas town. Its name survives only in occasional street names in the counties around Lamesa and Big Spring.

***

The story of the Soash Company and its namesake West Texas town is but one of the hundreds of boom-bust stories to be told throughout the colonization history of Texas and the greater West. Its uniqueness lies in the fact that so much money was spent on marketing and promoting the city using the height of early 20th century printing technology. The booklets created for Soash are a time capsule of high hopes, speculative marketing, urban planning, early 20th century prairie architecture and irrational exuberance during the waning years of Westward expansion. The Soash saga is a classic example of a man’s reach exceeding his grasp, but its legacy for the present may well be as a snapshot into the mindset of a Wild West-style capitalism and the marks it left – physical and psychological – on the history of our state.

Sources Consulted

Soash, TX on the Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hvsaj)

William Pulver Soash on the Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fso01)

“Why You Should Invest in the New Town: Soash, Texas” from the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections (From the physical copy in the holdings of The Texas Collection)

“The Big Springs Country of Texas” from the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections (From the physical copy in the holdings of The Texas Collection)

“Why You Should Buy a Farm in the Big Springs Country on the South Plains of Texas” from the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections (From the physical copy in the holdings of The Texas Collection)

3 comments for “(Digital Collections) The Rise and Fall of the Soash Empire: A West Texas Hard Luck Story”