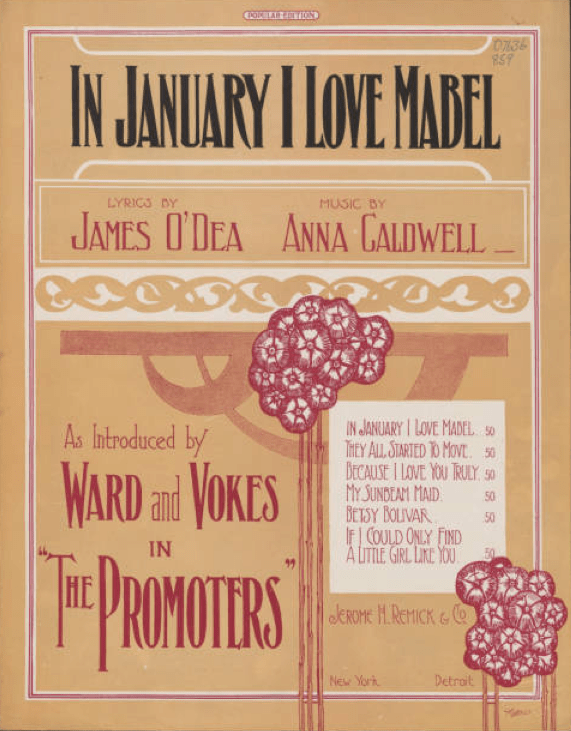

Sometimes inspiration strikes in strange ways. Take this week’s blog post, for example: while conducting a simple search in the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections for terms related to the new year – New Year, January, cold as a well digger’s elbow, etc. – I came across a piece from the Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music titled, In January I Love Mabel.

“That sounds interesting,” I thought to myself, so I clicked into the item and checked out the lyrics.

I’ve a loving disposition, I’ve put sorrow on the shelf

I believe in that old maxim “Love your neighbor as yourself”

Now, it happens that my neighbors are a bunch of girls divine

And their views upon the subject are identical to mine

But to love them all together would I’m sure create a fuss

So to head off squally weather, I’ve arranged to love them thus.CHORUS

In January I love Mabel, in February I love Lou,

In March, little Fay, in April and May, I cuddle both Irene and Sue

In June and in July I’ve Rose and Lily, in August and September Flo and Doll,

October and November, Jess and Bess, but please remember

In December I’m not stingy, so I love them allQuite a very good arrangement, I have found my plan to be

When of number two I’m weary, bliss I find in number three

Then again the girl for Summer, not to speak of Spring of Fall

In the dreary days of Winter simply will not do at all

Girls are more are less like flowers, at their best a month or so

I have studied well the subject and I think I ought to know

Hoo boy, that’s a lot to take in.

Leaving aside the blatantly lunkheaded (and borderline misogynistic) lyrics, it conjures up a number of questions.

1.) Who is the protagonist of this piece? What makes him think he’s so special as to have a different lady for every month of the year?

2.) Was this meant to be a serious piece (surely not!) or is it an example of early 1900s satire, humor or light comedy stylings?

3.) Why can’t a girl who’s perfectly acceptable in the summer be found adequate in the winter?

4.) Just where in the world did this piece come from?

While the first three questions may require a little digging, it was the answer to the fourth that led me down a rabbit trail with no good answers and became the basis for this post.

Ward and Vokes and The Promoters

A quick glance at the cover for the piece reveals it to be part of a stage production called The Promoters, created by the comedy duo of Ward and Vokes. According to a post on the Performing Arts Archive, Hap Ward and Harry Vokes were vaudeville performers whose comedy show partnership lasted more than thirty years. The men would have been in their early forties in 1909, the year The Promoters would likely have debuted.

As is common with many, many pieces from the Spencer Collection, In January I Love Mabel featured an inset on the cover that lists other pieces from The Promoters’ score, including tracks called They All Started to Move, My Sunbeam Maid, If I Could Only Find A Little Girl Like You and a somewhat befuddling piece called Betsy Bolivar.

It turns out, we’ve added a scan of Betsy Bolivar to the Spencer Collection, so perhaps a quick recounting of its lyrics will give us some clues to the nature of The Promoters. To wit:

Betsy B. was young and simple, Betsy was a dunce

All the boys, on viewing Betsy, fell in love at once

One she met, who pleased her greatly till in jest he spoke,

Said “my dear, it would appear, you’re not quite city broke.”CHORUS

Oh, you Betsy, Betsy Bolivar,

Tho’ you’ve never been out at night, You’ll get along all right, all right.

For oh, you Betsy, What a Queen you are,

“I may be a rube, but I’m no boob,” said Betsy Bolivar.Betsy wandered to the city, where she rubber’d ’round,

City chaps were different from the boys at home she found,

Ev’ry day it seemed to her she stood for, so to speak,

More falls than you could see at old Niagara in a weekOh, you Betsy, Betsy Bolivar,

Tho’ you’ve never been out at night, You’ll get along all right, all right.

For oh, you Betsy, What a Queen you are,

“For a girl so young I’m pretty well stung,” Said Betsy Bolivar.

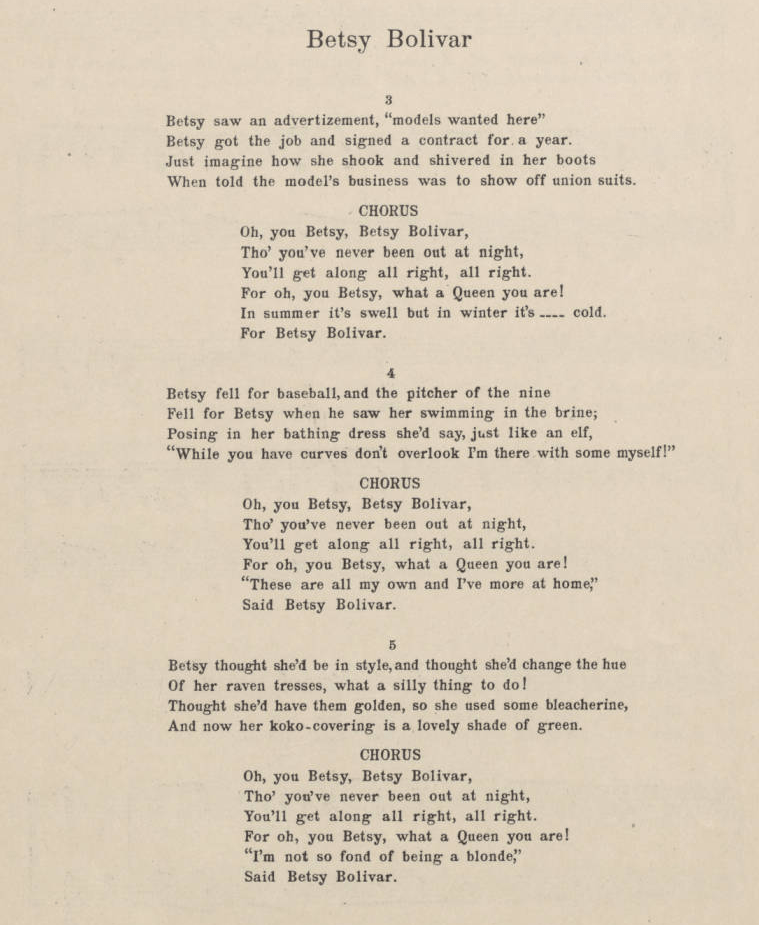

And it goes on like this for three more verses. Take a look for yourself!

So Betsy’s not a much more appealing character than our nameless paramour from In January, I Love Mabel. Her main attributes seem to be that she’s a pretty, dark-haired girl who’s not too bright but whose physical charms are more than ample to snag the attention of a baseball pitcher … until she uses “bleacherine” to dye her “koko-covering” (hair) and it turns out a “lovely shade of green.”

So Betsy’s not a much more appealing character than our nameless paramour from In January, I Love Mabel. Her main attributes seem to be that she’s a pretty, dark-haired girl who’s not too bright but whose physical charms are more than ample to snag the attention of a baseball pitcher … until she uses “bleacherine” to dye her “koko-covering” (hair) and it turns out a “lovely shade of green.”

All of this plays pretty handily into stereotypes found throughout the early 20th century stage pieces found in the Spencer Collection, particularly the light comedies, comedic operas and vaudeville productions. What makes it more interesting is that the music for both pieces was composed by Anne Caldwell, a prolific writer of Broadway and popular music who happened to be married to James O’Dea – the lyricist for both pieces from The Promoters.

What does all this mean? Probably not much. After all, it’s a play so unimportant that it doesn’t even have a Wikipedia entry. (In a time when events as obscure as the Kentucky meat shower have entries, it takes a lot to be so disposable.) But wouldn’t it be fun to imagine what the general outline of the story must have been, based solely on the lyrics to these two pieces (and the titles of the remaining five)? Here’s my take!

Act I

We open on a young man dressed in the height of early 1900’s fashion as he sits on a bench in a crowded city scene. He bemoans his lack of success in finding a suitable mate and sings a song of lament to the cover of his favorite magazine: an image of a raven-haired young woman of stunning beauty (If I Could Only Find A Little Girl Like You). After his song is finished, he realizes he is running late for an appointment and begins to run through the crowded streets toward a streetcar stand. Just as he arrives, the crowd around the stand parts (They All Started To Move) and our hero sees a woman standing inside a departing streetcar. She is beautiful, with dark hair and arresting blue eyes. He is immediately smitten but dismayed as the streetcar pulls away before he can climb aboard.

Act II

The scene opens on the woman from the streetcar as she walks through the door of her small but stylish apartment. She, too, is suffering from a case of amorous upset, but her particular malady is that she still pines for a boy from her hometown who came to the big city years ago and with whom she has lost contact. As she swoops around her apartment, she belts out a song of lament (Because I Love You Truly) and dreams of the day she will reunite with her lost love somewhere on the streets of the Big City, far from her small-town roots.

After her big number is finished, she slips behind a changing screen and reemerges dressed for her shift at the local small appliance manufacturer where she works the midnight shift while hoping to break into show business as a model or actress. The scene changes, and the girl is seen working a shift on a production line, where she fits covers onto electric toasters. The other women on the line sing a silly song about the girl who is too pretty to work in manufacturing (My Sunbeam Maid), but she is oblivious to the fact that they are singing about her! The scene ends with the girl leaving the factory at the end of her shift. As she walks through the factory gates, she is spotted by an unscrupulous talent agent (one of the promoters of the show’s title) who recruits her to work a job as a model for a local clothing store. The girl gleefully accepts the offer and runs off-stage toward her apartment.

Act III

It is three years later, and the girl – whose name is Betsy Bolivar – has become a world-famous actress on the stage. She is known for her stunning good looks and goofy demeanor, but she is still brokenhearted over the loss of connection with her hometown beau. In a neat bit of staging, we see Betsy sitting at a dressing table backstage for her latest big show, while in the audience is none other than our lovestruck young man from Act I!

As Betsy primps backstage, the young man sings a song to his companions about the world-renowned beauty who will grace the stage in mere moments: Betsy Bolivar. As he sings, Betsy comes onto the stage and performs a comedic dance number to her eponymous tune. The young man is transfixed: it’s the girl from the streetcar, all those years ago! He still hasn’t forgotten her; in fact, he’s more in love than ever, and he takes the opportunity to sneak backstage after the show and tell her so by means of a ridiculous song about his vain search to find a suitable companion (In January I Love Mabel), which is obviously a poor replacement for a lifelong attachment to Betsy, his one true love.

And now, the big twist: it turns out the young man is none other than the boy from Betsy’s hometown, gone all these years to “make it big in the Big City!” Betsy is delighted, and the two instantly reconnect as they sing a duet reprise of Because I Love You Truly. The scene ends with Betsy and the young man in a fond embrace as the curtain falls on their reunited love. Aaaaaaaand, scene!

If all of that sounds farfetched, I encourage you to go read the synopses for practically any boy-meets-girl stage production from the period and you’ll see it’s not entirely off base.

And now it’s your turn: if you’ve got an alternative storyline for our heroes from In January, I Love Mabel and Betsy Bolivar, leave them in the comments below. You’re a creative bunch; don’t let me down!

***

For more pieces from the Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music, visit the collection’s homepage.