This blog post was composed by Aaron Ramos, master’s student in the History Department.

The 1950s often evoke images of nostalgia for simpler times in American life. This longing is illustrated through the popularity of the 1950s Americana aesthetic which situates the ideal life amid white suburban spaces where the nuclear family reigns and the American economy booms. However, any careful study of the 1950s will demonstrate that such nostalgia is representative of a fictive interpretation of the decade. The decade was marred by American military engagement in Korea, unabashed racialized violence, and the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation. Another struggle the nation faced during the 1950s was the push to weed out subversive influences from the media Americans consumed, particularly American youth. Subversive influences included anything from communist/leftist undertones to characters/storylines that put consumers at risk for moral decay. In his book, The Cool and the Crazy: Pop Fifties Cinema, Peter Stanfield states that media during the 1950s exploited moral panics as they related to juvenile delinquency, gang culture, substance abuse, and deviant sexual practices. [i] As such, comic books and their impact on readers fell under the scrutiny of the federal government.

The 1950s also coincided with the Golden Age of comics. Many of the characters we know and love debuted during this time, including Captain America, Wonder Woman, Green Arrow, and Shazam. During this Golden Age, comic books were published and circulated widely, and the archetypes were laid for more beloved characters that would emerge during the Silver Age of Comics, such as the X-Men, the Hulk, and Spider-Man, among others. Even so, superheroes were not the only characters dominating the pages of comic books in the 1950s. Crime, horror, and detective comics also reached peak popularity during this time such as Tales from the Crypt and Crime SuspenStories.

Published by EC Comics, Crime SuspenStories was a popular title during the Golden Age of Comics. The title featured crime thrillers influenced by the film noir genre, and they depicted horrifying episodes of murder, greed, and other violent crimes. Many cover illustrations portray people (primarily women) in life-threatening situations. With the Cold War in full swing and fears of perceived moral decay abounding, many started to fear the impact that comics such as Crime SuspenStories would have on the nation’s youth, and the O.C. Fisher papers housed at the W. R. Poage Legislative Library highlight this moral panic.In a letter addressed to Representative Fisher, a coalition of women from Trinity Lutheran Church in Miles, Texas entreated Fisher to support legislation that would stop the production of comics such as Crime SuspenStories. They believed such actions would “…defend the minds of our young citizens against the obscene onslaughts of the [so-called] comic books.” [iii]

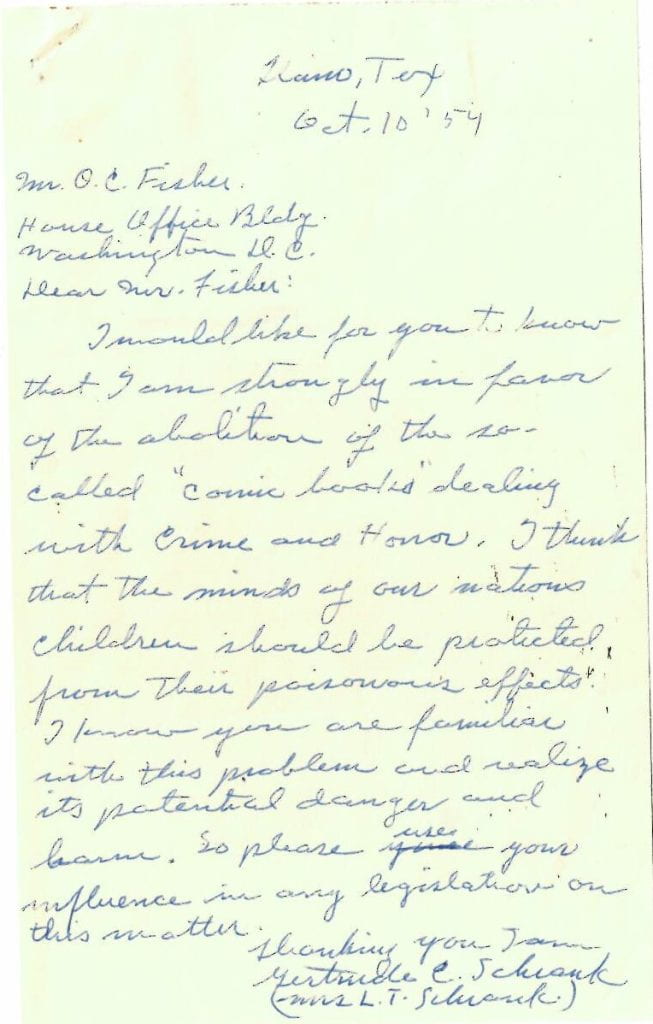

In a different letter, Mrs. L.T. Schrank of Llano, Texas wrote that she was in complete favor of banning all comic publications. Schrank wrote that “…the minds of our nation’s children should be protected from [comics’] poisonous effects.” [iv]

Fisher himself was in favor of restricting the publication and distribution of comic books. In a letter dated May 11, 1954, Fisher wrote to a constituent in Comstock, Texas that he voted to pass a bill in the House of Representatives that would restrict the use of the Postal System in distributing comic books and other “salacious literature.” [vi]Experts on education and child psychology also contributed to the discourse surrounding the impact of media on youth. In a 1955 study, the Review of Educational Research set out to examine the impacts of media consumption on children. When discussing comic books, author Evelyn Banning stated that “[e]xcessive comic book reading was termed a symptom of maladjustment.” [vii] Even so, Banning makes no effort to define what constitutes a maladjusted child/childhood.

Despite the moral panic and efforts to restrict the production and consumption of comic books, the medium has remained a mainstay in 21st-century American culture. Even horror comics have survived various censorship campaigns with titles like The Walking Dead ranking among the most critically acclaimed titles of the 2000s. Furthermore, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has just released its 33rd comic book film with The Marvels, which features characters who have captivated comic book readers ever since the late 1960s. In short, comic-based media is here to stay.

Still, the O.C. Fisher papers remind us that the mid-20th century was a contentious time for Texans and Americans in general. The issues they dealt with sometimes intersected with pop culture, and the aforementioned letters attest to the power of visual media. Even though the push to ban comics in the 1950s emerged within the context of the Cold War, efforts to ban/censor the media that children consume continue today. This begs the question: to what extent do American children enjoy the same rights to freedom of speech and expression as their parents? Collections like those housed in the Baylor Collections of Political Materials at Poage Library may not answer this, but they do help us to understand where we fit in regarding civic life and duty in the United States, and how we can challenge or affirm our relationship to the country.References

[i] Stanfield, Peter. “Got-to-See: Teenpix and the Social Problem Picture.” In The Cool and the Crazy: Pop Fifties Cinema, 69–89. Rutgers University Press, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt163tbmp.7.

[ii] Craig, Johnny. Cover of issue #1 of CrimeSuspenstories. 1950. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crime_SuspenStories#/media/File:Crime_SuspenStories_1.jpg.

[iii] Matteson, D.C. Letter to O.C. Fisher. Miles, Texas, August 22, 1954. O.C. Fisher papers, Accession #46, Legislation, Comics, Baylor Collection of Political Materials, W.R. Poage Legislative Library, Baylor University.

[iv] Schrank, L.T. Letter to O.C. Fisher. Llano, Texas, October 10, 1954. O.C. Fisher papers, Accession #46, Legislation, Comics, Baylor Collection of Political Materials, W.R. Poage Legislative Library, Baylor University.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Fisher, O.C. Letter to J.L. Newton. Comstock, Texas, May 11, 1954. O.C. Fisher papers, Accession #46, Legislation., Comics Baylor Collection of Political Materials, W.R. Poage Legislative Library, Baylor University.

[vii] Banning, Evelyn I. “Social Influences on Children and Youth.” Review of Educational Research 25, no. 1 (1955): 36-47. https://doi.org/10.2307/1169997.

[viii] The Marvels. 2023. Accessed from: https://www.movieposters.com/products/marvels-mpw-137252?gad_source=1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI5aKi4peAgwMVixCtBh0zrQ4ZEAQYASABEgKXI_D_BwE.

2 comments for “(BCPM) Comic Book Banning in the United States: Days of Future Past”