A recently-released biography of Julia Ward Howe by Elaine Showalter titled The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe paints an intriguing picture of an early American abolitionist and feminist whose unhappy marriage bred two works of creative genius: The Battle Hymn of the Republic (1861-1862) and a less-well-known book of poetry called Passion-Flowers (1853). You can read an excellent review of The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe over at Jezebel.com.

A recently-released biography of Julia Ward Howe by Elaine Showalter titled The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe paints an intriguing picture of an early American abolitionist and feminist whose unhappy marriage bred two works of creative genius: The Battle Hymn of the Republic (1861-1862) and a less-well-known book of poetry called Passion-Flowers (1853). You can read an excellent review of The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe over at Jezebel.com.

In this post we will examine the first edition of Passion-Flowers made available online in our Digital Collections as part of the 19th Century Women Poets Collection, drawn from the holdings of the Armstrong Browning Library.

A Brief Biography of Julia Ward Howe

Before we get into Passion-Flowers, it’s a good idea to get some basic facts about Howe’s life. She was born into a family of means in New York City and rubbed elbows with eminent persons of the day like Charles Dickens. She married Samuel Ridley Howe (known by his nickname, “Chav”) in 1843 and went on to give birth to six children. Her marriage was notoriously unpleasant for her, and she began writing poetry as a form of cathartic therapy; when her husband found out she was writing such explicitly negative and critical poetry about her marriage, the strain on their marriage increased.

Howe was inspired to write Battle Hymn of the Republic after meeting President Abraham Lincoln. She set the lyrics to the tune of John Brown’s Body and it became an instant sensation in the North and has been synonymous with the Civil War ever since. Upon her husband’s death in 1876, she discovered that nearly all the money she’d brought into the marriage from her father’s estate had been lost, squandered by Samuel on bad real estate deals.

In the last decades of her life, Howe became involved in the nascent women’s rights movement, ultimately serving or leading numerous groups in the fight for women’s suffrage and various Christian causes. She died in in 1910 at the age of 91. She was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and her home in Rhode Island, called Oak Glen, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. (To learn more about Howe’s amazing life, read her Wikipedia entry, from which many of these facts were gleaned.)

Passion-Flowers

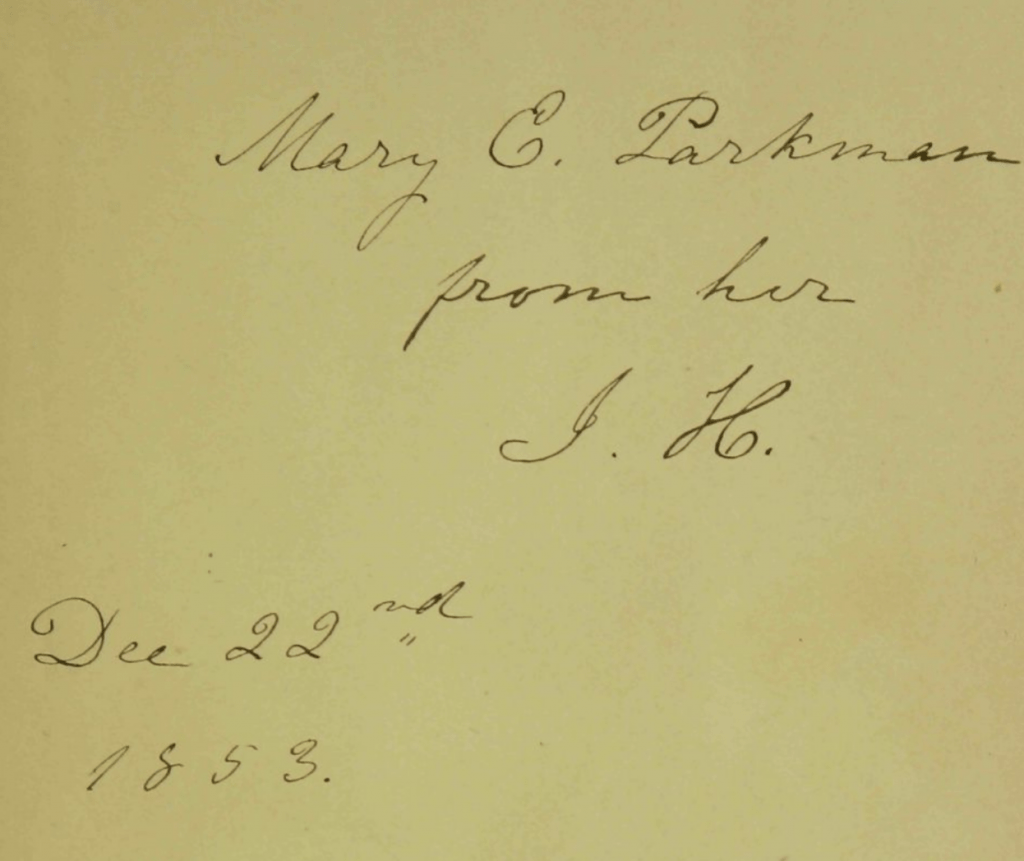

Inscription on inside cover of the ABL’s edition of “Passion-Flowers.” It is autographed by Howe and addressed to Mary C. Parkman

The copy of Passion-Flowers is asserted to be a first edition, based largely on the inscription found on its inside cover. Here, we see a dedication of the volume to Mary C. Parkman, signed by “J.H.” and dated December 22, 1853. This would mark the book as being part of the initial publication run and thus containing the unedited versions of the poems that would later be “toned down” after her husband’s angry reaction to the picture they painted of Howe’s domestic life.

The poem referenced in the review above, “Mind Versus Mill-Stream,” is a sharp criticism of a man’s belief that he can woo and marry a strong, willful women and then expect her to be docile and easily channeled into the role he sees her playing in the relationship. The whole notion is wrapped up in a metaphor about a miller who wants to harness a wild-running stream to run his mill, only to find the spirited body of water cannot be tamed for long. It is reproduced here in its entirety for your enjoyment.

“Mind Versus Mill-Stream”

Julia Ward Howe, 1853

A Miller wanted a mill-stream,

A mild, efficient brook

To help him in his living, in

Some snug and shady nook.But our Miller had a brilliant taste,

A love of flash and spray,

And so, the stream that charmed him most

Was that of brightest playIt wore a quiet look, at times,

And steady seemed, and still,But when its quicker depths were stirred,

Wow! but it wrought its will.And men had tried to bridle it

By artifice, and force,

But madness from its rising grew,

And all along its course‘Twas on a sultry summer’s day,

The Miller chanced to stop

Where it invited to ‘look in

And take a friendly drop.’Coiffed with long wreaths of crimson weed,

Veiled by a passing cloud,

It looked a novice of the woods

That dares not speak aloud.Said he: ‘I never met a stream

More beautiful and bland,

‘Twill gain my bread, and bless it too,

So here my mill shall stand.’And ere the summer’s glow had passed,

Or crimson flowers did fade,

The Miller measured out his ground,

And his foundation laid.The Miller toiled with might and main,

Builded with thought and care;

And when the Spring broke up the ice

The water-wheel stood thereLike a frolic maiden come from school,

The stream looked out, anew;

And the happy Miller bowing, said,

‘Now turn my mill-wheel, do!’‘Your mill-wheel?’ cried the naughty Nymph,

‘That would, indeed, be fine!

You have your business, I suppose,

Learn too that I have mine.’‘What better business can you have,

Than turn this wheel for me?’

Leaping and laughing, the wild thing cried,

‘Follow, and you may see.’The Miller trudged with measured pace,

As Reason follows Rhyme,

And saw his mill-stream run to waste,

In the very teeth of time.‘Fore heaven!’ he swore, ‘since thou’rt perverse,

I’ve hit upon a plan;

A dam shall stay thine outward course,

And then, break out who can.’So he built a dam of wood and stone,

Not sparing in the cost,

‘For,’ thought our friend, ‘this water-power

‘Must not be lightly lost.’‘What? will you force me?’ said the sprite;

‘You shall not find it gain;’

So, with a flash, a dash, a crash

She made her way amainThen, freeing all her pent-up soul,

She rushed, in frantic race

And fragments of the Miller’s work

Threw in the Miller’s face.The good man built his dam again,

More stoutly than before;

He flung no challenge to the foe,

But an oath he inly swore:‘Thou seest resistance is in vain,

So yield with better grace.’

And the water sluices turned the stream

To its appointed place.‘Aha! I’ve conquered now!’ quoth he,

For the water-fury bold

Was still an instant, ere she rose

In wrath and power fourfoldWith roar and rush, and massive sweep

She cleared the shameful bound,

And flung to utterness of waste

The Miller, and his moundMORAL.

If you would marry happily

On the shady side of life,

Choose out some quietly-disposed

And placid tempered wife,To share the length of sober days,

And dimly slumberous nights,

But well beware those fitful souls

Fate wings for wilder flights!For men will woo the tempest,

And wed it, to their cost,

Then swear that took it for summer dew,

And ah! their peace is lost!

Friends, this is no subtle metaphor: a business-minded man seeks to tame a wild and free resource for the benefit of his work, and despite his best efforts, the nature of the stream is such that he is wrecked by its unbounded power. It’s no wonder that her husband – and, no doubt, the men in his social sphere – would be embarrassed and scandalized by its plain language, insinuation of marital unhappiness and allusions to a man losing control of his wife in a very public way.

Another poem that expresses both regrets and a subdued brand of hope is “Behind the Veil.” In this brief work, Howe tries to put into perspective the equal parts longing and dread that inhabit all human beings; the desire to know the future without having to suffer its consequences, and to seek a silver lining in the direst of circumstances.

“Behind the Veil”

Julia Ward Howe, 1853

The secret of man’s life disclosed

Would cause him strange confusion,

Should God the cloud of fear remove,

Or veil of sweet illusion.No maiden sees aright the faults

Or merits of her lover;No sick man guesses if ’twere best

To die, or to recover.The miser dreams not that his wealth

Is dead, as soon as buried;

Nor knows the bard who sings away

Life’s treasures, real and varied.The tree-root lies too deep for sight,

The well-source for our plummet,

And heavenward fount and palm defy

Our scanning of their summitWhether a present grief ye weep,

Or yet untasted blisses,

Look for the balm that comes with tears,

The bane that lurks in kisses.We may reap dear delight from wrongs,

Regret from things most pleasant;

Foes may confess us when we’re gone,

And friends, deny us present.And that high suffering which we dread

A higher joy discloses;

Men saw the thorns on Jesu’s brow,

But angels saw the roses.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Thoughts on Howe’s Poetry

In the review linked above, the reviewer makes a mention of the fact that Howe took some “swipes” at the Barrett-Brownings in her poetry, and from the text of a letter sent by Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford on June 6, 1854 we can see that EBB had no little amount of criticism for Howe, as well.

Portion of a letter from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford dated June 6, 1854. EBB references Howe’s book “Passion-Flowers” and offers her thoughts on Howe’s abilities as a poet. From the Margaret Clapp Special Collections at Wellesley College via The Browning Letters project.

Mrs Howe’s [book, Passion-Flowers] I have read since I wrote last. Some of them are good—many of the thoughts striking, & all of a certain elevation. Of poetry however, strictly speaking, there is not much; and there’s a large proportion of conventional stuff in the volume. She must be a clever woman. Of the ordinary impotencies & prettinesses of female poets she does not partake, but she cant [sic] take rank with poets in the good meaning of the word, I think, so as to stand without leaning– Also, there is some bad taste & affectation in the draping of her personality–

You can read more of the Brownings’ correspondence that references Howe in the Browning Letters project.

The works contained in Passion-Flowers may not have risen to Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s definition of “poetry,” but they certainly embodied a spirit and confrontational attitude that gained her some measure of fame and attention from a population of America’s women who saw her resistance to traditional gender roles as a way of pushing back against the lives they were expected to live, at least in the eyes of their male acquaintances. And while Howe would gain her greatest notoriety – and lasting fame – from the important lyrics she penned during the American Civil War’s earliest hours, her work in Passion-Flowers should also become required reading for anyone interested in the mindset behind one of America’s most influential 19th century women.

Read more books in the 19th Century Women Poets Collection here. Learn more about the correspondence of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning in The Browning Letters project.