As the work to post the audio of the final years of Dr. George W. Truett’s long career continues apace, I was generating a transcript for his sermon of January 3, 1943 when a story caught my attention. Truett uses a fair number of what I privately call his “modern day parables” to help illustrate his points. Often taking the form of inspirational (or, at times, admonishing) tales drawn from his years in the ministry, they tend to recount stories of anonymous people he’s encountered over the years (“a prominent business man,” or “one of the leading citizens of this state” and the like) whose circumstances illustrate a point he’s driving home in the message.

The wording of this particular story was so striking as to seem outlandish; I admit, for a moment I wondered if Dr. Truett was inserting a tale woven from whole cloth just to see if his audience was paying sufficient attention. The transcript of this story will illustrate the basis for my skepticism:

“We’re to make the best of a so-called accident. A man in this city, years ago, had his arms ground off in a mill. But the young fellow, undaunted, fixed him up some steel arms and went on with his studies and his work, diligently, and became one of the most prodigious toilers of our community, and came to a great judgeship and set a great example of fortitude and high behavior, enough to thrill any man capable of being thrilled by heroic behavior.”

“Sweet creamery butter!” I said to myself. “This has all the makings of a direct-to-cable inspirational movie of the week! Gruesome accident? Check! Hardworking young man refuses to give up, stays focused on his goals? Check! Man acquires high position, inspires humanity? Check and check! How is it that I’ve never heard of this man before?”

It turns out that while Dr. Truett may have gotten a (fairly major) detail about the story wrong, the actual story of Quentin Durward Corley was certainly remarkable enough to inspire both Truett’s use of his life story in a sermon and, later, the life of one of Baylor’s most remarkable graduates.

The “Armless Wonder” of Dallas

Corley was born in 1884 in the town of Mexia, Texas, a rough-and-tumble oilfield town about 45 minutes’ drive from Waco. According to this well-written blog post about Corley’s life, he worked as a bookkeeper and stenographer after graduating from high school before striking out for a career in civil engineering.

His life made a major shift in 1905, however, when he fell off of a train in Utica, New York. The accident left him without his entire right arm and the left arm from the elbow down. What could have been a life-ending circumstance instead served as a source of inspiration for Corley, whose amazing life was only just beginning.

Displaying a strength of will – and cleverness – rarely seen in this or any other decade, Corley set about finding a way to overcome his limitations. He invented – and later patented – an artificial limb for his left arm that featured interchangeable elements such as eating implements (a knife), a simple hook and a pincer.

Judge Quentin D. Corley drives his automobile with the aid of his self-designed prosthesis. Courtesy the Library of Congress via Wikipedia.

If all of this seems far-fetched to modern readers accustomed to our medical wizardry springing forth from laboratories, clinical studies and pharmaceutical manufacturers, it is helpful to remember that Corley came of age only a generation or so removed from the end of the most catastrophic conflict in American history: the Civil War, in which thousands of men returned to their homes maimed and scarred, many missing limbs following gruesome battlefield amputations. It is reasonable to assume that during his childhood in Mexia, Corley would have been exposed to such men at least once a year during the annual Confederate reunions held there between 1889-1946. These gatherings of former Rebel soldiers were major events for the city, and it would seem likely that Corley would have seen and even interacted with amputees at these events, so his experience with artificial limbs may have been more frequent than that of an average citizen.

After studying law at the firm of Muse & Allen in Dallas, Corley was elected justice of the peace in 1908 and was rewarded for his work by being elected county judge in 1912. Corley proved himself a capable administrator and arbiter of the law, earning accolades from his voters and the nickname “Armless Wonder,” a shockingly un-PC moniker to modern audiences but no doubt offered in a spirit of respect by those he served in the 1910s.

Corley’s story would be inspiring enough if it stopped at this point, and, in fact, that is probably how Dr. Truett would have known it to end. What he might not have known – despite a relationship with Baylor University that stretched back to the late 1800s and a lifelong closeness with the school – was how Judge Corley’s life would directly impact that of another young man who faced similar challenges and dreamed of similar successes.

“Baylor Students Complain Over Nothing … How Would They Do If They Were Hindered as Frank Coleman?”

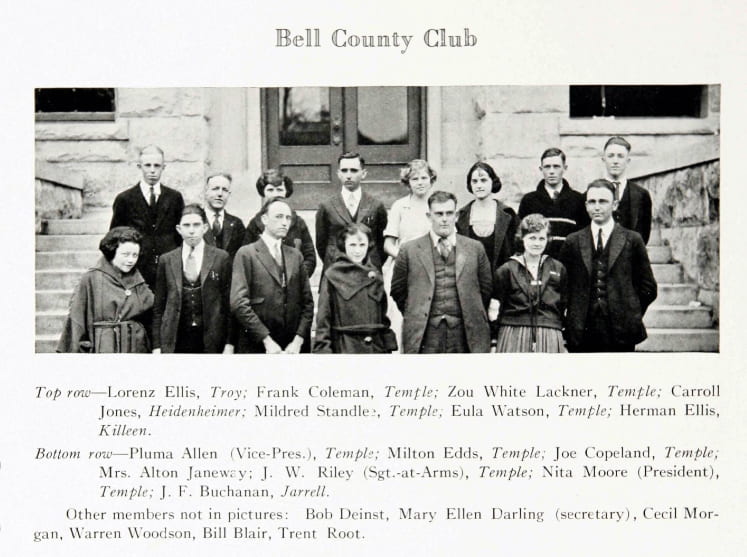

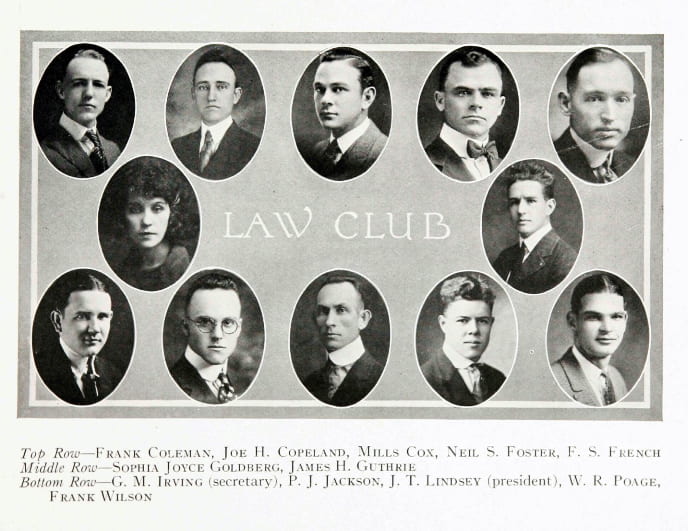

Frank G. Coleman was born without arms and only one leg. This fact opens a rather blunt – but no less inspiring – piece in the January 26, 1926 issue of the Baylor Daily Lariat. The reason for the piece is Coleman’s place on the ballot for judge in Bell County, Texas, where he practices law in the city of Temple. Coleman was a 1925 graduate of the Baylor Law School and, by all accounts, led a remarkable life prior to finding himself in the running for county office.

A look into previous coverage of Coleman’s story in the Lariat fills in some of the details. A “Freshman” edition of the Lariat from March 3, 1921 – which was edited by Coleman, incidentally – includes a write-up of his life captioned, “Frank Coleman First Armless Person in Baylor.” It goes on to detail his early life and disposition – “one of the happiest and best-liked fellows around the University,” who apparently gave himself the nickname the “Finless Fish” during his first year – and tells of his first encounter with Judge Corley.

Coleman was a user of Corley’s patented prosthetic arms, and in the spring of 1918, Coleman joined him for a tour of government hospitals housing disabled veterans of the First World War. Intended to “[bring] new hope to disabled veterans by showing them how, though maimed[,] they could become useful, happy citizens,” the younger man discovered an interest in becoming a lawyer, perhaps due to Judge Corley’s own story of triumph over adversity. Coleman would enter Baylor Law School and graduate in 1925. He returned to Temple to practice law.

He appears in the pages of the Lariat again in 1926, with a story that details his appearance on the Democratic primary ballot for judge of Bell County. Unfortunately, his presence in the historical record, at least in terms of Internet-accessible materials, seems to end here. I have been unable to find any evidence of the results of the 1926 election or of Coleman’s later life, though I will document any future findings as updates to this post.

***

The intertwining stories of Dr. Truett, Judge Corley and “Finless Fish” Coleman are an example of the ways in which a single twist of fate – a misstep from a train in Utica, NY – can affect the lives of countless others, even at a distance of more than a century. Corley’s early patents in prosthetics led to advances in the field that would bring us today’s carbon-fiber artificial legs and remarkably realistic prosthetic arms. Coleman’s inspirational story would bring comfort to wounded veterans and encourage his fellow Baylor Bears to greater heights of academic and personal achievement.

And the story of the judge with the “steel arms” told by Dr. Truett to his audience of parishioners on the first Sunday of a new year would be recorded for prosperity on a 16” transcription disc that would find its way to Baylor’s Texas Collection and, eventually, to the world via the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections.