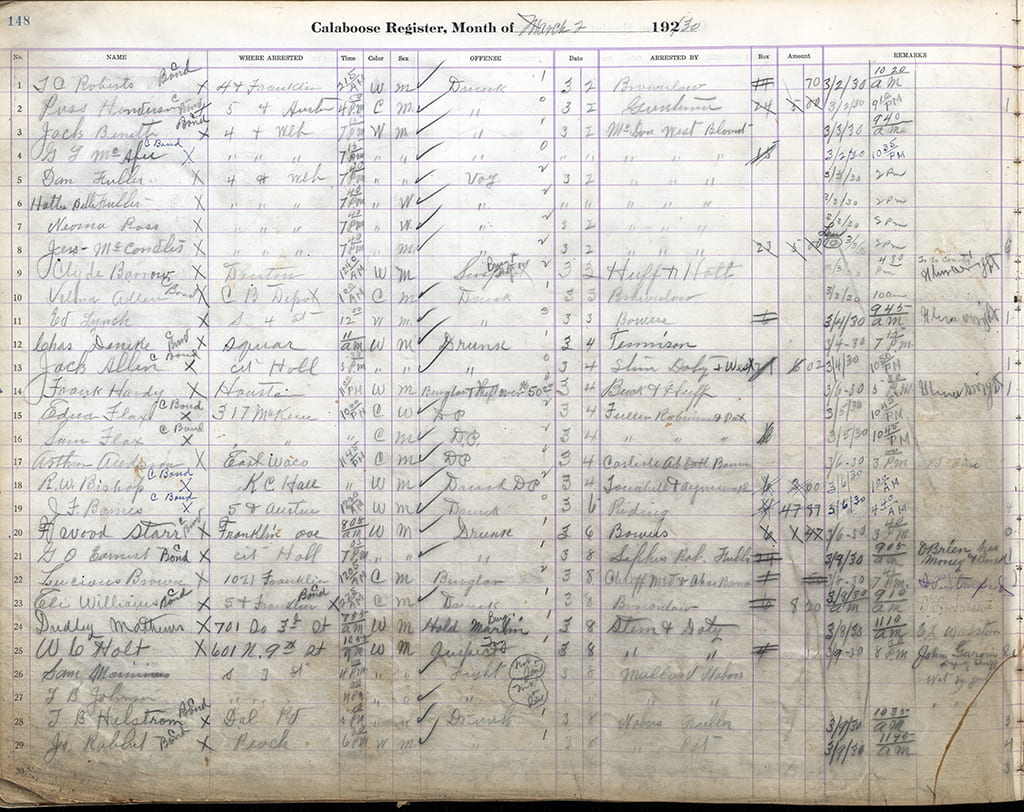

A page from the “Calaboose Register” of McLennan County, ca. 1930.

From the Pat Neff Collection, The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, Texas. (Click to enlarge)

Frank Jasek, the library’s resident bookbinder and preservationist extraordinaire, wheeled the book truck into my office, his face aglow with mischief.

“Have you ever seen one of these before?” he asked, gesturing to a large bound volume measuring about a foot tall by two feet wide. The words “CALABOOSE REGISTER” were stamped on its cover. “No,” I answered Frank. “I can honestly say I have not.”

With a knowing smile, he opened the register’s cover and began turning its lined pages, each covered with orderly columns of pencil-written text. “’Calaboose’ is an old slang term for ‘jail,’” Frank said. “This particular register lists all the people booked into the McLennan County jail between the late 1920s and the mid-1930s.”

He finished turning pages and pointed his finger at an entry on line number nine, page 148, dated March 1930. “Do you recognize that name?” The information, written by a nameless clerk almost a century ago, was easily legible. It read, in part:

Clyde Barrow. Denton. 12.40 AM. Suspect burglary theft of car.

The McLennan County Jail booking information for Clyde Barrow, March 3, 1930.

From the Pat Neff Collection, The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, Texas. (Click to enlarge)

And that’s when I realized that sitting in my office was an artifact from Waco’s direct connection to one of crime’s most infamous duos: Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, known to the world as Bonnie and Clyde.

The First Temptation of Bonnie Parker

When nineteen-year-old Bonnie Parker of Cement City, Texas (a Dallas suburb) met Clyde Barrow in January of 1930, she was a married woman. However, her husband had been in jail since January 1929, so Bonnie was free to fall head-over-heels for the brazen young man with the criminal past. According to most reports, Bonnie and Clyde became inseparable almost from the start. But it wasn’t until March of 1930 that Bonnie’s adoration for Clyde would push her across the line separating infatuation from criminality.

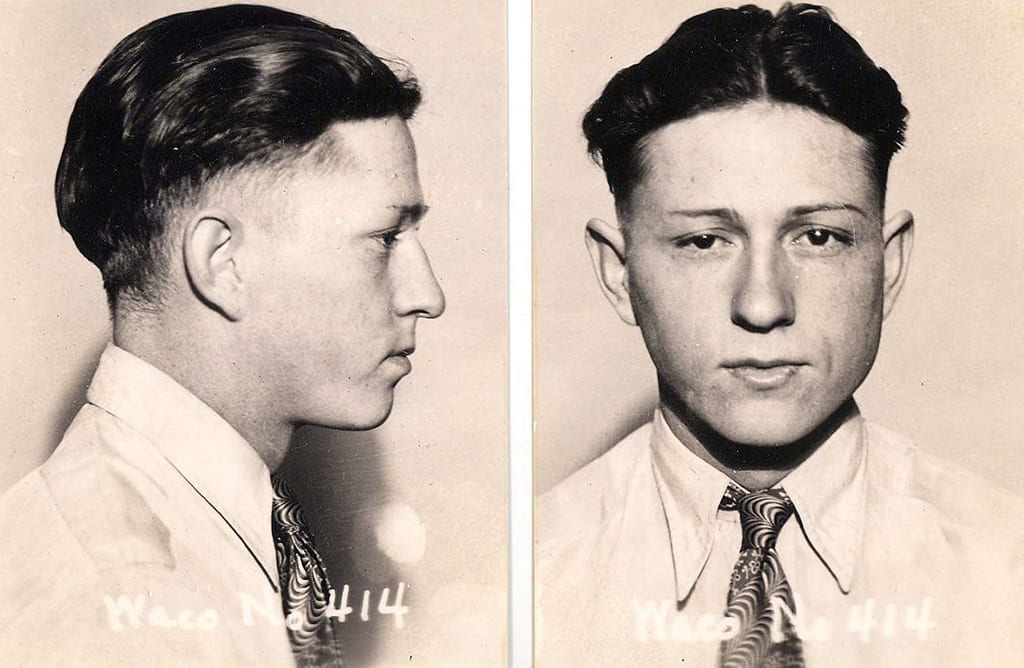

Clyde Barrow’s mug shot from the McLennan County jail, March 1930.

(Image courtesy the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, Texas)

Clyde Barrow was wanted on criminal counts out of Waco, and he was arrested in Denton County on March 2, 1930. He was transferred to Waco by officers Holt and Hatt on March 3 and on March 5, Clyde pleaded guilty to a total of seven criminal charges filed in McLennan County, including a charge of stealing W.W. Cameron’s automobile. (Cameron’s name is synonymous with Waco history due to his decision to donate hundreds of acres of land to the city of Waco in memory of his father, William Cameron; the land was named Cameron Park in his honor.) Clyde was sentenced to serve two years in the state jail at Huntsville. While awaiting transfer, he shared a cell with two petty criminals named Willie Turner and Emery Abernathy. Together, they hatched a plan for a daring escape, but for it to succeed they would need someone on the outside. Bonnie fit the bill perfectly.

Turner had hidden a gun in a home located at 625 Turner in East Waco. (Sadly, this building has long since been demolished.) If someone could retrieve it and smuggle it into the jail, they could steal the keys from a jailer and make their escape. Bonnie, who had been visiting Clyde repeatedly during his incarceration, agreed to help. On the afternoon of March 11, she retrieved the gun and secured it under her dress using a belt worn around her chest. A 1956 Argosy magazine article picks up the story from there:

“The night before moving Clyde to Huntsville from the Waco Jail, Bonnie brooded for several hours and then made preparations to go see Clyde in jail. Bonnie got a few minutes to tell Clyde good-bye and that was just enough time. From outside the cell, the jailer saw only the lover’s [sic] farewell embrace, but Bonnie whispered in Clyde’s ear, ‘Put your hand inside my blouse, honey.’ Clyde got a surprise; in between her breasts Bonnie had hidden a snub nose revolver. Bonnie shielded Clyde from the jailer’s eyes and Clyde shifted the gun to his pocket. Bonnie said, ‘Be careful, sugar,’ kissed him and left the jail.” (Argosy magazine, March 1956)

Although Clyde claimed he threw the gun used in his jailbreak into an Ohio river while on the lam from Waco, some scholars believe it was a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson revolver similar to this one, currently on display at the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco, Texas.

(Photo courtesy the TRHFM)

Later that night, the Waco Times Herald reports:

“About 7:30 p.m. Tuesday night Jailer I.P. Stanford, unarmed, went to the second floor of the jail where the three were confined, to carry Turner a bottle of milk. When he opened the door of the cage he was stopped by Turner, then Abernathy poked a gun in to his ribs and ordered Stanford to ‘stick ’em up.’ Stanford was locked in a cell after he was robbed of his keys. Huse Jones, on duty at the turnkey’s desk downstairs, was then held up, and keys to the final jail door taken from him.” (Waco Times Herald, March 12, 1930)

The men fled into the night, dodging bullets fired by jail staff. They stole a series of cars on their way out of Waco, ultimately evading arrest for a week before being rearrested in Ohio. At the time, no one suspected Bonnie’s part in the jailbreak; the Times Herald’s coverage did not note anything “that even remotely linked Clyde’s female visitor” to the act (Guinn, 2009). Bonnie had committed her first criminal act and no one was the wiser.

The story of Bonnie and Clyde’s reunion and subsequent crime spree – and its bloody end in a shoot-out in rural Louisiana – became the stuff of legend. To this day, there are discrepancies and points of dissent woven throughout their brief, violent time together. In some cases, it can be hard to know exactly what is fact and what is fiction.

Which makes the rest of our story today even more fitting.

Governor Neff’s Collection

In our own way, the subject of this post – the calaboose register – is another part of the Bonnie and Clyde mystery. That’s because its provenance is only partially established, and as with any great mystery, it may never be fully solved.

We know for a fact that the register came to Baylor as part of the Pat Neff Collection. Neff, who served as governor of Texas from 1921 to 1925 and president of Baylor University from 1932-1947, left a huge collection of materials behind as part of The Texas Collection’s holdings. The materials cover such a large swath of Texas and Baylor history that it crosses over lines demarcating the University Archives and the Special Collections. It contains materials created by Neff during his time at Baylor and his time in Austin, as well as artifacts and documents he collected during his lifetime.

Which is why it is difficult to establish with certainty when the calaboose register became a part of Neff’s collection. Was it given to him by someone from McLennan County? Did he acquire it at an estate sale? Was it part of his law library or a curiosity he rescued from the scrapheap on a whim? To date, the exact path the register took from the desk of a McLennan County clerk to the collection of a former Texas governor is open for further research.

Just Another Day in the DPG

One question we can answer is how it came to the Digitization Projects Group. When Frank walked through our door with the register on a book truck, he had just finished restoring its cover. Benna Vaughn, the Special Collections and Manuscripts Archivist at The Texas Collection, had sent the register to Frank for repair after she spotted some mold damage on the binding. Frank expertly replaced the damaged section of the binding and even managed to preserve the original cover. Over the course of many hours spent poring over the volume in the course of his work, Frank noticed the dates covered by the volume and used his memory of the Clyde Barrow jailbreak to locate the entry seen above.

We routinely see these kinds of materials moving through the Riley Digitization Center. They are not scheduled as part of a larger collection but our expertise in scanning makes us a prime spot for people to bring materials like this. In some cases it’s because one of our colleagues knows someone in the DPG has an interest in the subject. In others, it’s a matter of sharing something too exciting to keep under wraps. For the most part, these one-offs will not make it online – although the register may one may day as part of the Pat Neff papers – but they do provide an opportunity for us to keep our scanning skills sharp, and sometimes they lead to a fun opportunity to share a story with a wider audience, as we’ve undertaken to do here.

If you’d like to see the Clyde Barrow calaboose register for yourself, call the fine people at The Texas Collection and ask to see the item from the Pat Neff Collection with ties to a high-stakes jailbreak involving two of America’s most notorious folk criminals. They’ll know exactly what you’re talking about.

For more great information on Bonnie and Clyde, including a display of weapons associated with their notorious partnership, visit the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco. Special thanks to Mary “Kate” McCarthy (Collections Assistant) and Shelly Crittendon (Collections Manager) for their most excellent help with this article.

Sources Consulted

Guinn, Jeff. Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde. Simon and Schuster, 2009.

Ramsey, Winston (ed.). On the Trail of Bonnie and Clyde: Then and Now. Battle of Britain Prints, 2003.

Veit, Richard. “The Waco Jailbreak of Bonnie and Clyde.” Waco Heritage and History magazine. December 1990.

“Killer in skirts.” Argosy magazine. March 1956. From the vertical files of The Texas Collection.

“Jail Break in Waco Was Early Episode in Clyde Barrow Career.” Waco Tribune Herald. October 26, 1975. From the vertical files of The Texas Collection.

Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker entries from the Texas Sate Historical Association’s “Handbook of Texas Online” (www.tshaonline.org)