By Melinda Creech

Graduate Assistant, Armstrong Browning Library

The following paragraph appears in the Oxford National Dictionary of Biography in an article entitled “Women Artists in Ruskin’s Circle,” written by Jane Garnett:

In his first lecture in the Slade series Ruskin had already surprised his audience by turning from a discussion of Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones to praise of two women artists, prefacing his comments with the statement: ‘For a long time I used to say … that, except in a graceful and minor way, women could not paint or draw. I am beginning, lately, to bow myself to the much more delightful conviction that nobody else can’ (Complete Works, 33.280). Both of these women lived out Ruskin’s principles of profound religious engagement with nature. One of them was the American Francesca Alexander (1837–1917), to whom Ruskin had been introduced in Florence in 1882. She was at this point forty-five and had been a professional artist for twenty years, although Ruskin was to talk of her as if she were a young girl, and addressed her as ‘lassie’ and as his ‘sweetest Sorel’. She had been brought up by her artist father in Ruskinian ways of looking at nature, and as a devout evangelical. At the age of seven she was said to have announced that she wanted to be an artist and to work for poor children. She collected stories and songs from the Tuscan peasantry, which she wrote and illustrated with figure drawings of the poor, many of whom gathered regularly in her studio, and whom she supported with the proceeds of sales of her work. For Ruskin her work—in both its form and its subject matter—embodied an ideal Christian and artistic simplicity and sincerity. He was to focus on this ideal in remembering—and transfiguring from its religious narrowness—the character of Rose La Touche. He bought and published Francesca Alexander’s The Story of Ida, Roadside Songs of Tuscany, and Christ’s Folk in the Apennine. In his third Slade Lecture he read passages from her preface to the Roadside Songs, and showed some of her drawings; and in June 1883 he gave a drawing-room lecture in London at which he showed twenty of her drawings. The Spectator review, commending their excellence, saw them as exemplars of Ruskin’s teaching.

The Armstrong Browning Library owns two letters from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin.

In this letter Francesca tells Ruskin about the discussion in which her little group of Bellosguardo friends had participated regarding the drawings of flowers in her book, Roadside Songs of Tuscany:

I must tell you though what some of them said about the Road Side Songs, (which they nearly all saw before it went to you) you may be pleased, now that the book belongs to you, to have the favourable opinion of such distinguished judges as meet in the “brilliant society” of my Sky-parlour. They all seemed principally interested in the pictures of flowers, which brought about a discourse on flowers in general, causing Edwige to remark, what I believe she thinks she has discovered, and what really I don’t believe people think so much about as they might . . . that each flower has just the leaves that are most becoming to it. Then, taking the Easter flowers on the table for a text, poor gentle Bice, with tears in her eyes, improvised a little sermon, (better than many that I have heard in church) on their variety and wonderful contrivances for beauty, as showing the hand of the Creator. “And only think,” said a Contadina woman, contemptuously, “that now-a-days people try to make out that it is only nature who does it all!” At which Edwige said, yet more contemptuously: “It is all very well; and I hear a good deal about inventions in these times . . . but it is my belief that they will wait a good while before anybody makes another invention like those flowers: and if they think it is so easy, they had better try themselves!” Then the Contadina returned to the flowers of the Road side Songs, which she said “Seemed to have all the colours of the real ones, and yet were made of nothing but ink!” And she did not believe I could have done it by myself: probably the angels came and showed me how. And finally Edwige ended the discourse by saying triumphantly: “you will never see any more books born, like that!”

This letter expresses Francesca’s concern for Ruskin’s well-being. She says:

Some things in your letter trouble me: you seem dissatisfied with Joanie, and . . . I hope I am wrong, but I keep thinking about that miserable time two years ago, when there came about a separation between you, and you suffered more than ever, since I have know you, (as you told me afterwards yourself) and she fell dangerously ill, and as for me . . . Well, I don’t like to think about it! The end of it was, that it half killed you both; and, if you knew the terror that comes over me at the thought of any difference between you and her, you would have patience with whatever I say! You don’t explain what the trouble is, and I ask no questions. You speak as if she worried you . . . But do remember that she is worn out now, with her anxiety during your illness, and is probly [sic] weak and nervous, and worried all the time for fear of your hurting yourself in some way. But I dare say it is foolish in me to be so frightened. Only I am so far away, and have suffered much for my fiends, in these last years; and now I am always dreading some harm coming to you, or to her, whom you have taught me to love.

The Armstrong Browning Library also owns three copies of Roadside Songs of Tuscany in various forms. However, none of the editions contain parts 9 and 10.

The Alexanders, who lived near Florence are mentioned several times in the Brownings’ letters.

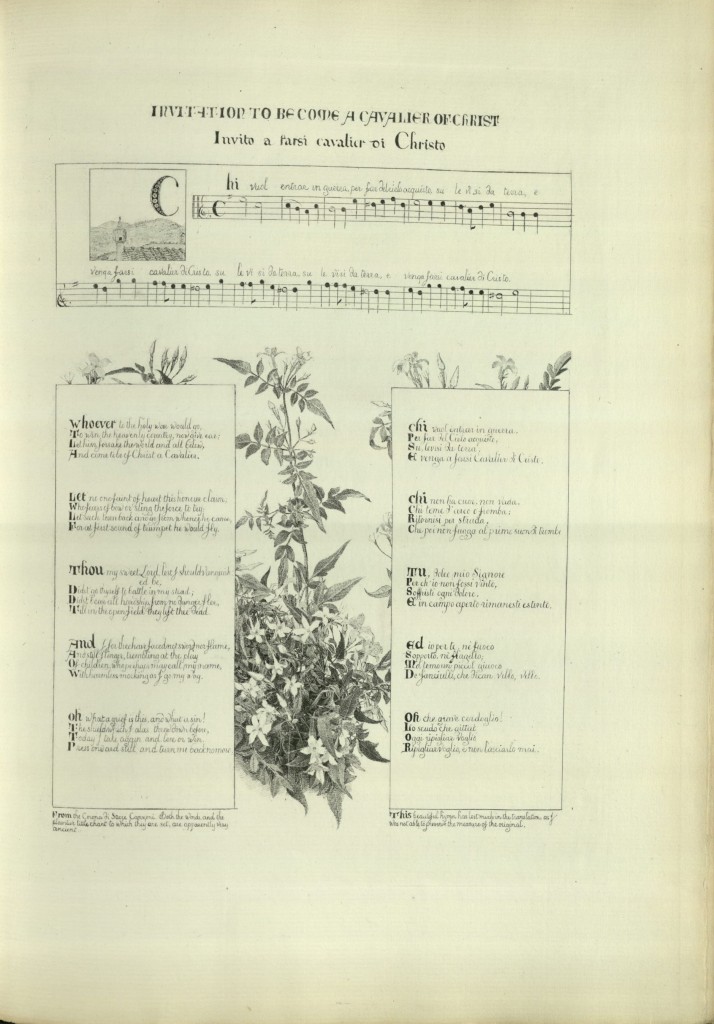

In 1897 Francesca Alexander published an edition of Tuscan Songs that did not include John Ruskin’s notes but did include the music of the folk songs that she had collected, along with her lovely illustrations of the flowers from along the roadsides of Tuscany.

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-1-zu023x-1024x680.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 2.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-2-1j5hcqf-1024x674.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-3-1bp156v-1024x675.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-April-1885-4-2f4omtz-1024x674.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. April 1885]. Page 1.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-1885-1887-1-1kvnc63-1024x668.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 2.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.1885-1887-2-1kifm1n-1024x678.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 3.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.1885-1887-3-21hv1d0-1024x671.jpg)

![Letter from Francesca Alexander to John Ruskin. [ca. 1885-1887]. Page 4.](https://blogs.baylor.edu/armstrongbrowning/files/2016/11/Alexander-to-Ruskin-ca.-1885-1887-4-1hkh6d7-1024x652.jpg)